“—You have never known a Woman’s body!

—I have known the body of my mother, sick and then dying.”

Roland Barthes, Mourning Diary

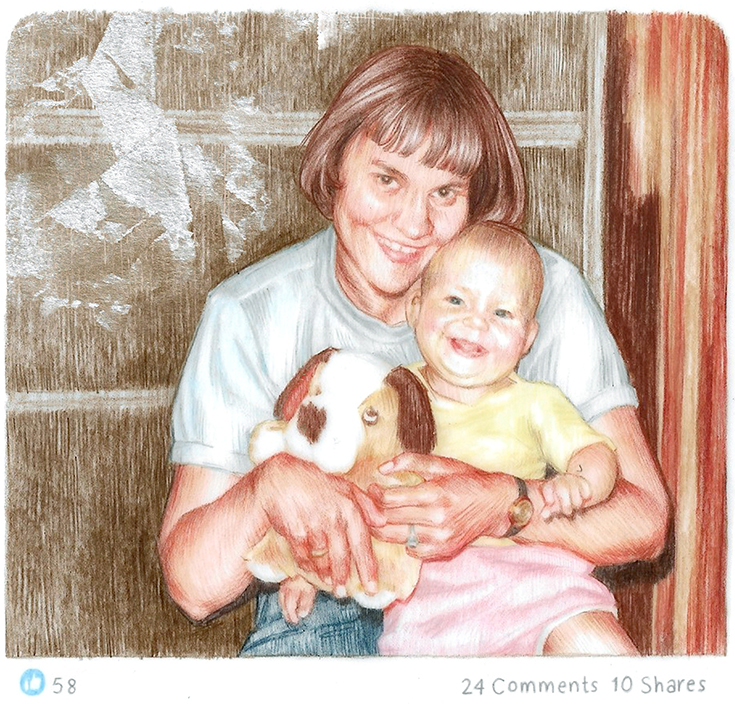

I learned the news of my mother’s death on Facebook. I had left her the day before, tiny swimmer in an Olympic-sized hospice bed. Her parched mouth was open, but her breathing was wet. When I kissed her forehead, she smelled salty, sweet—a sticky, human smell.

I read the news of her death sitting in Pearson airport, stress eating a hamburger. I was heading back to stupid London, where I had a stupid job interview I was not prepared for. When I had kissed my mother in her hospice bed, she was still alive and full of desire. She wanted to swim. I, too, needed her to be alive. I’d asked everyone not to disclose anything mother related until my interview was done, worried I wouldn’t board the plane. And then, instantly, she was gone because my uncle posted it on Facebook.

Forty minutes later, I was standing in the middle of a Boeing 767. I hadn’t known what else to do. I tried to fit my bag above my seat, but it wouldn’t fit. I panicked. I approached the flight attendant, weeping. My bag doesn’t fit and I just found out my mother died on Facebook. I was instantly upgraded.

Serious question: If your mother dies on Facebook, is it true?

In 2015, Facebook announced a new policy that allows you to designate a “legacy contact” who is allowed to pin a post on your timeline after your death. The contact can’t log in or read private messages but can respond to friend requests, archive posts, etc. Before, Facebook profiles of the deceased could only be “memorialized,” deleted or left unchanged after death.

I found this out after my sister and I spent hours trying to guess my mother’s password, which turned out to be frustratingly obvious.

There was some comfort in finally getting my mother’s password right. It was like a test, a sibling competition to see how well we knew her. My sister won, but I was a close second. When we finally cracked the code, we didn’t know what to do. It was suddenly too intimate to see her whole digital life splayed out before us. We scrolled endlessly. Months later, I had the same feeling seeing my mother’s wedding ring on my hand in a different country: a reminder something world altering had occurred.

There was some comfort in finally getting my mother’s password right. It was like a test, a sibling competition to see how well we knew her. My sister won, but I was a close second. When we finally cracked the code, we didn’t know what to do. It was suddenly too intimate to see her whole digital life splayed out before us. We scrolled endlessly. Months later, I had the same feeling seeing my mother’s wedding ring on my hand in a different country: a reminder something world altering had occurred.

I was charmed by the fact that my mother’s Facebook friends were mostly family, that her news feed featured the same names over and over. I have often thought about paring down my own friend list this way. I also noticed that my mother seemed fixated on posting about Canadian social issues—dying with dignity, ADHD awareness, Amber Alerts: missing children from Thunder Bay, missing children from Midland, from Montreal, from Aylmer, from Clifford, from North Vancouver, from Kenora. So many missing children. A pang—What was she trying to say?

Marshall McLuhan: “The new electronic interdependence recreates the world in the image of a global village.”

What I don’t know: What does it mean to exist in an image that will outlive you?

In 1977, when Roland Barthes lost his mother, he returned to live in the apartment he had shared with her. The apartment became a fixture in his grief. He did not want to live in the apartment, but he also knew there was no other place. The furniture took on a life of its own: “As soon as someone dies, frenzied construction of the future (shifting furniture, etc.): futuromania.”

When my mother died, I had not lived with my parents for many years, and I lived in a different country with very little furniture to shift. Instead of re-positioning the couch, I obsessively reread my mother’s Facebook messages.

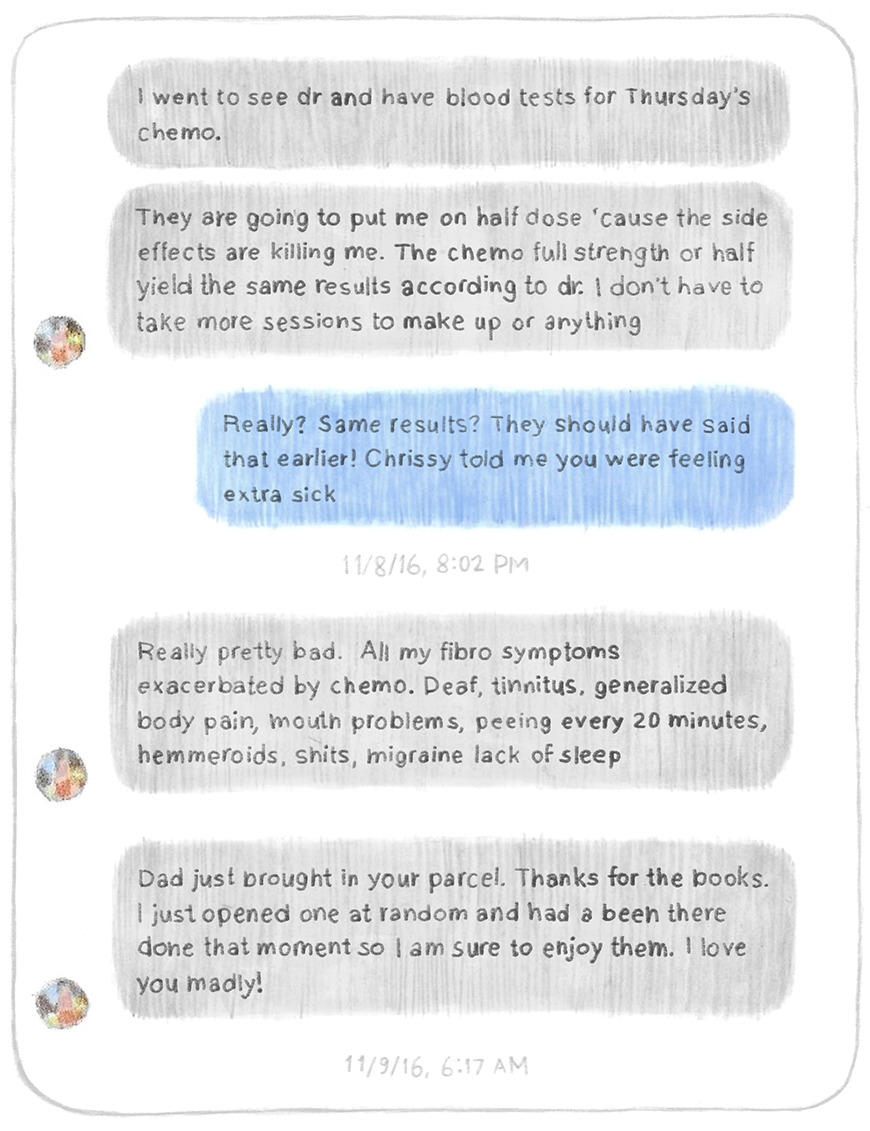

Eventually, my mother had become too sick to talk on the phone. Most of our conversations took place on Facebook Messenger at incredibly odd hours.

Barthes: “In the sentence ‘She’s no longer suffering,’ to what, to whom does ‘she’ refer? What does that present tense mean?” In my old Facebook messages, my mother is still alive—suffering and symptomatic in the middle of the night.

Serious question: How to mourn when your mother becomes an avatar?

Barthes: “Don’t say Mourning. It’s too psychoanalytic. I’m not mourning. I’m suffering.”

Is Facebook my mother’s digital urn?

After his mother died, Barthes wrote: “Since maman’s death, my life has not managed to constitute itself as memory. Flat, without the vibratory halo of ‘I remember . . . ’”

I, too, have had trouble remembering. I arrived home in Canada the night before my mother went into the hospice. I know I brought my mother’s favourite foods: strawberries and whipped cream, pasta salad, chips and dip. But I can’t remember what we said to each other. I asked my sister later, but we could only vaguely remember what we had talked about. The next morning, my mother fell out of bed and went straight into hospice care, where she was heavily sedated. A week later, she was dead.

I consulted my last Facebook messages, but they were of little help. Toward the end, my mother was too sick to answer.

This is the trouble with any urn, digital or otherwise—it doesn’t hold the right kind of data.

After my mother died, my father and I struggled to find the “perfect” urn. Eventually, we settled on an antique copper jug that she had owned—the kind you would find with matching water basins in a southern Ontario farmhouse. It seemed correct, but I was troubled by the lack of a lid. I wondered how my mother would have felt if she’d known that she would eventually be put inside a copper jug that she had chosen as decor.

I called my sister to discuss the choice of jug. A long silence on the end of the line. “But it doesn’t have a lid.”

Barthes: “Sometimes, very briefly, a blank moment—a kind of numbness—which is not a moment of forgetfulness. This terrifies me.”

Also Barthes: “No sooner has she departed than the world deafens me with its continuance.”

We decided on a celebration of life instead of a funeral. We catered it with all the foods my mother liked. As I couldn’t afford a second ticket home from Europe, my sister Facebook video’d me into the service.

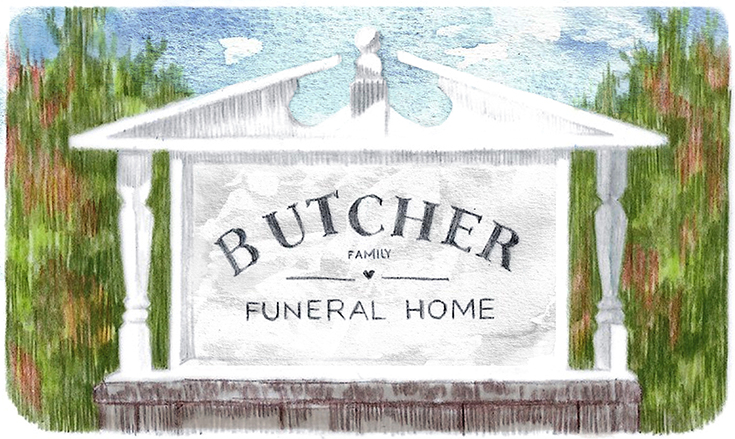

The funeral home was just as I remembered it from my grandmother’s service, an untouched relic of the ’80s: turquoise carpeting and light-pink walls. It had recently changed ownership, but when we were growing up, it had been called the Butcher Family Funeral Home. The sign used to be a running joke on the internet because the word “Butcher” was in large letters over smaller letters that read “Family Funeral Home.” My father, a typesetter, declared it a perfect example of why the art of typesetting isn’t dead. My sister and I had always thought of it as perfectly normal when we were growing up, since we knew all the Butcher kids. We didn’t understand why people kept pulling over to take pictures of the sign with their phones.

My sister switched to her front camera, to show me the urn, and indeed it looked quite wonderful with a spray of white and yellow roses and wildflowers around it. She’d polished the jug, she mentioned, because she’d decided my mother wouldn’t want to be put inside any piece of copper that wasn’t perfectly buffed.

She asked if I wanted to say anything, but I couldn’t think of anything to say. I couldn’t bring myself to video chat with the jug. I could only imagine my mother laughing mercilessly from the next room as I said goodbye to part of her dining room set.

What bothered me, of course, was death deranging my grasp of the object. The copper jug was mimicking life. It demanded cleaning and maintenance. It was standing there, cruelly immortal, and my mother was not.

When Barthes returned home to his mother’s apartment, he tidied his “new” living space. “Around 6 p.m.: the apartment is warm, clean, well-lit, pleasant. I make it that way, energetically, devotedly (enjoying it bitterly): henceforth and forever I am my own mother.”

Serious question: How do you make your dead mother continue to live?

Recently, on Facebook, a green dot lit up beside my mother’s name. My heart swelled and then plunged into my stomach. Of course my mother is not online. It is only my sister on my mother’s account: another avatar.

The problem with Facebook is that it is so incredibly alive. Even without an avatar, there’s always a cache, a backup, a screenshot. The posts we publish are the digital furniture that remain after all other abandonments have occurred.

It is unclear how Barthes intended to publish his mourning diary. For two years after his mother’s death, he jotted fragments on 330 individual slips of paper. These were not published until twenty-nine years after his own death. Perhaps he hoped the fragments would eventually gel into a fluid form.

Neil Badmington, in The Afterlives of Roland Barthes: “To write loss is to honour love and what has been lost, but ‘making literature out of it’ involves accepting death, accepting the empty room, and accepting this, moreover, in language which, as language, honours no singularity.”

Barthes: “Despair: the word is too theatrical, a part of the language. A stone.”

For Barthes, images also present us with a multitude of semiotic confusions.

For instance: at the university, someone asked me how I was. I said I couldn’t stop thinking about a bathing suit my mother used to wear. This isn’t what I meant, exactly, or maybe it is.

To me, the bathing suit was iconic of my mother. I had a clear image in my head. Recently, at H&M, I found one with a similar pattern and sent my sister a picture on Facebook.

We both knew immediately that it was not exactly right. A simulacrum with no original.

Barthes, too, understood this. “What we have is a new space-time category: spatial immediacy and temporal anteriority, the photograph being an illogical conjunction between the here-now and the there-then.”

On Facebook, my mother is caught in a film reeled backwards: leaping out from churning water, waving her arms—leaving a perfectly smooth surface behind her.

McLuhan: “One thing about which fish know exactly nothing is water, since they have no anti-environment which would enable them to perceive the element they live in.”

Digital time will not right itself.

My mother swimming farther and farther away.

Like Barthes, I provide no monument for my mother. Only fragments—a tissue of quotations in the wrong order.

Barthes: “There’s no text without filiation.”

Also Barthes: “Everything pains me. The merest trifle rouses a sense of abandonment.”

On the day of his own death, Barthes left an unfinished essay curled in his type-writer, titled: “One Always Fails to Speak of What One Loves.”

Every sentence struggling against its own momentum.

Every image, a punctum, a wound.