Rachel Snow is a member of the Wesley band, a Juris Doctor graduate from the University of Saskatchewan, a First Nations legal advocate—and, in the eyes of the Chiniki band (a band that, together with the Wesley band and the Bearspaw band, forms the Stoney Tribal Administration), a dangerous dissident.

In October 2018, the Chiniki band sued Snow for a million dollars over a Facebook page she created to help rally people to the “no” side of a referendum being held by the Stoney on a controversial land deal. Her online comments included allegations of financial mismanagement and impropriety against the chief and council. Just weeks before the vote, Chiniki Chief Aaron Young served her with a cease-and-desist notice, accusing her of libel.

In an interview with news website RMO Today, former judge John Reilly described the lawsuit as “an effort by tribal governments to limit free speech.” Another way to see it is as a SLAPP—or a “strategic lawsuit against public participation.” SLAPPs are lawsuits that saddle someone with litigation costs in order to intimidate them into silence, effectively censoring them. In fact, the suit against Snow was the second time in 2018 alone that the Stoney sued a band member for comments posted online.

Such suits are just some of the many punishments meted out by band officials across the country against outspoken members of their own reserves and even against Indigenous media. These alleged reprisals have included intimidation by police acting on band orders, physical altercations by band staff, loss of jobs, and ostracism. Some band members have been cut off from band resources, others have been banished—a form of exile. In a recent case, the Sandy Lake First Nation, in northern Ontario, banished two nonmembers, a woman and her son, as punishment for her partner’s political disputes with the band. In sum, reserve governments have used every tool at their disposal to limit the right of their citizens to speak freely.

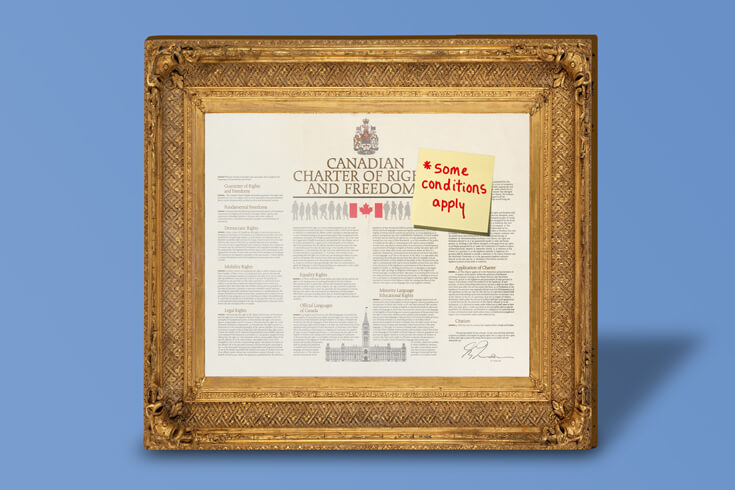

None of this, of course, should be allowed to happen. Section 2 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees every Canadian citizen “freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication”—meaning the government, within certain limits, is prohibited from taking actions that restrict these rights. First Nations citizens, like other Canadians, enjoy these freedoms in their relationships with the federal and provincial governments. However, it’s unclear if the clause applies to First Nations governments. There is almost no case law on extending free speech protections to reserves.

One of the few precedents that exist is a 2003 Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench decision. In Horse Lake First Nation v. Horseman, the band administration of Horse Lake had taken legal action against band members who were protesting and posting signs that called for “forensic audits” and “mandatory drug testing for Chief and Council.” In his ruling, Justice J. Lee wrote: “I believe that the Charter does apply to Aboriginal Reservations and Bands, and the Charter would protect freedom of expression with respect to Band Council matters.”

Justice Lee’s is a lonely voice, and without a decisive federal court ruling affirming the right of free expression on reserve, that right languishes in ambiguity—an ambiguity that allows band councils to take action against their members with seeming impunity. It needs to be said that the lack of case law likely has less to do with the number of potential litigants than it does with the cost of a court case, the risk faced by a band member if they lose, and, most importantly, the absence of civil-society organizations willing to advocate for us. While Snow was able to raise more than $6,000 for her legal costs through an online fundraiser, one thing she hasn’t done as part of her legal defence is reach out to organizations like PEN Canada or the Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA). Snow doesn’t believe they can help her. Her apprehensions aren’t misplaced. When I asked the BC Civil Liberties Association (BCCLA) to make a statement on civil liberties violations on reserves, they balked, saying that, in their view, Section 2 of the Charter did not apply to First Nation governments. “I hope you understand,” they wrote.

I didn’t. The BCCLA, the CCLA, and PEN Canada, among others, have funded and intervened in numerous court cases to defend and expand the Charter rights of Canadians. The CCLA, in partnership with the BCCLA, Canadian Journalists for Free Expression, and PEN Canada, currently operate a website called the Censorship Tracker. The site posts examples of censorship in Canada between 2006 and 2015. None of those incidents are on First Nations reserves, and there is no place to choose “First Nations Band” on their censorship reporting form.

I spoke with PEN Canada executive director Brendan de Caires. His organization’s vision statement declares that it “envisions a world where writers are free to write, readers are free to read, and freedom of expression prevails.” To that end, its Canadian Issues Committee “has fought censorship in more than 70 cases—from book seizures at the border and censorship in schools and libraries, to legislation that threatens the freedom of expression of all Canadians.” During our call, de Caires says that, to the best of his knowledge, PEN hasn’t been involved in any First Nations free speech cases in Canada—though he says that “we are very aware that we need to be far more engaged on it.”

That engagement is vital. Without the participation of civil-liberties organizations, the cost of litigation will mean that Section 2 of the Charter will continue to have an asterisk next to it—one that reads “not counting Natives.”

First Nations citizens aren’t alone in experiencing blowback from their own communities for exercising free speech. Indigenous media pay a price too. In the early morning hours of October 28, 2019, a truck rammed into the offices of Turtle Island News—a weekly newspaper published on the Six Nations reserve, in southern Ontario. An unknown person doused the truck with gasoline and set fire to it and the newspaper’s office. Police described the arson as “targeted.” The newspaper’s publisher, Lynda Powless, called it “an attack on free speech and a free press in First Nation communities.” This was not the first time Turtle Island News had been attacked for reporting on Indigenous issues. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), a press-freedom group based in the United States, Powless’s outlet has received threats “over its coverage of local wealthy individuals and official misconduct.” In 2003, reports the CPJ, Turtle Island News was hit by gunshots “in retaliation for its coverage of rape allegations against a family member of a local official.”

Individual journalists have a tough time of it too. Last July, APTN reporter Beverly Andrews attended a news conference with members of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs (AMC), a lobby group representing nearly all of the province’s sixty-three First Nations. During a media scrum with Peguis First Nation, a government official swatted and then tried to grab a microphone out of Andrews’s hands for asking about allegations that AMC’s grand chief had texted unwanted messages to a young Indigenous woman. The official then expelled Andrews from the press conference. Following that confrontation, another member of the Peguis administration berated Andrews outside the building, saying “what’s so frustrating is that our own media is the first one to splash all our dirty laundry all over the place.”

Wawmeesh Hamilton has experienced similar moments of hostility. A member of the Hupačasath First Nation in Port Alberni, BC, Hamilton has reported on everything from Native sex offenders to Nisga’a citizens protesting their own nation’s deal with Pacific Northwest LNG over the pipeline project. These stories haven’t exactly made him popular with First Nations governments, whose members sometimes see his reporting as a kind of betrayal. “Councils say we don’t want issues internal to the nation aired in public,” Hamilton says. “The criticism I’ll get sometimes is that ‘you’re just trying to expose divisions in the community.’ Well, you know what? That crack was already there, and that person is free to express their opinion. It’s about the issue, not you.”

To better understand how widespread such attitudes might be, I sent a survey to band councils last June. Over the course of two weeks, I reached out to every band office I could find contact information for—about 500 of the 619 First Nations in Canada—and asked them for their views on free expression. I received twenty-five replies, from bands of different sizes and from a range of regions. It’s a small sample size, but the results are illuminating.

Only eight of the twenty-five bands polled, or 32 percent, found social media criticism of a chief or band councillor acceptable. Eleven of the bands—44 percent—had social media policies limiting acceptable expression on reserve. These numbers are especially worrisome when you realize that First Nations tolerance for online censorship is something oil companies appear eager to exploit. According the Yellowhead Institute, a First Nations–led research centre based at Ryerson University, an unsigned agreement drafted in 2016 between Wet’suwet’en First Nation and Coastal GasLink (official documents are unobtainable due to confidentiality clauses) required the First Nation to spy on and control any social media activity by band members that might “impede, hinder, frustrate, delay, stop or interfere with the Project’s contractors.”

Another area my survey looked at was the role of media on reserve. Many reserves are small and don’t have the numbers to support their own newspapers or radio stations—they are, in effect, news deserts. Because of that, it’s important that reporters from off reserve, Native or non-Native, be permitted to visit to conduct interviews and investigate. One reason the current Wet’suwet’en crisis in BC has deteriorated is the absence of on-the-ground reporting. Little reliable information exists about the hereditary chiefs who oppose the construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline. Mainstream coverage has offered up different, often contradictory facts about votes, support, and referendums—even the number of chiefs varies.

However, ten of the twenty-five reserves I polled say that they haven’t been visited by a reporter in the last five years—a number of them even say that they have never seen a reporter. It’s true that, in many instances, journalists are expected to ask permission to enter communities, and it’s not unusual for some to be turned away. But, according to Hamilton, a major reason non-Native media avoid stories about reserves is the fear of being portrayed as racist: “It’s too easy for nation officials to say, ‘You’re being a racist. You’re picking on a little First Nations group. You’re just part of a colonial structure that beat up on us and you’re doing it again.’ And who wants to get painted with that brush?”

It’s a fear that is perversely making First Nations people second-class citizens. One of the main outcomes of reporting is to get civil-liberties cases like Snow’s more widely known. If those issues aren’t identified by the press, it becomes easier for governments to subject band members to intimidation, band members have a harder time raising sufficient funds for their court cases, and the circle of repression continues.

Even without increased media coverage, civil-liberties organizations, like PEN, the BCCLA, and others, have a duty to reach out to First Nations people—people, not chiefs or band councils. These groups need to learn about the gaps in the Charter, they need to open their doors to First Nations activists, and they need to use their resources to champion free speech on reserve. Those rights are the same rights they themselves hold under the Charter as Canadian citizens. If they don’t hold these rights cheaply, then they should fight for them until they are universally recognized by every government in this country.