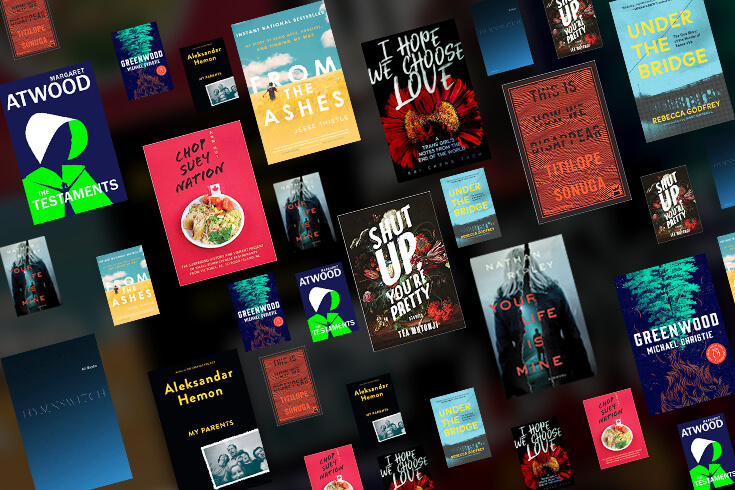

Shut Up, You’re Pretty by Téa Mutonji and Under the Bridge by Rebecca Godfrey

Mutonji had me at the title of this stellar collection, then she hooked me again with her first (excellent) story, “Tits for Cigs.” The linked tales here follow a young Congolese woman living in Toronto as she navigates the fraught terrains of race, sex, female friendship, and family. The voice is intimate and dangerous, hilarious and wise—totally addictive storytelling.

Rebecca Godfrey is one of my favourite contemporary writers. Torn Skirt, a raw fever dream of a novel, is the book I would live in if I could live in a book. Under the Bridge, her follow-up and a masterpiece of true crime, blew me away. Rereleased this summer, Under the Bridge recounts the stories behind the 1997 gang murder of fourteen-year-old Reena Virk in Victoria, British Columbia. Godfrey’s storytelling is vivid, empathetic, and challenging, and she brings everyone in this tragic story to life.

—Mona Awad is the author of Bunny and 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl.

I Hope We Choose Love by Kai Cheng Thom

I want to put Kai Cheng Thom’s magnificent essay collection in the hands of so many people: trans girls and queers who don’t know what to make of their own brethren; straight people who are unsure of how to navigate particular strains of leftist thought that have permeated the wider culture. I Hope We Choose Love: A Trans Girl’s Notes from the End of the World is full of honesty and generosity in the purest sense of each word. It reads like a gentle voice at your side saying, “Look, I know this is how it feels”—“it” being substance abuse, mental-health issues, intimate-partner violence, and supporting someone grappling with any of the above—“and I want to give you something else to consider.” In a time of extraordinary trans books sweeping the world (Hazel Jane Plante’s Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian) being one of the latest), Thom’s is a beautiful and urgent thing. I honestly can’t think of a single person in my life I wouldn’t give it to.

—Casey Plett is the author of A Safe Girl to Love and Little Fish, winner of the 2019 Amazon First Novel Award.

From the Ashes: My Story of Being Métis, Homeless, and Finding My Way by Jesse Thistle

This memoir haunts, gnawing at the soul as we walk with Jesse through his many incarnations. Now a professor of Métis studies at York University, Jesse tells his truths with the eyes of someone who has seen and experienced more than what seems bearable from such a young age. I can’t forget certain passages, such as when Jesse’s father takes him and his brothers to their local corner store to shoplift for the first time—food and snacks stuffed down Jesse’s pants—because they are starving. Or when the brothers hide from child-welfare authorities after being abandoned for days. If you want a glimpse at why some of our brothers and sisters wind up on the streets, read this book.

—Tanya Talaga is the author of Seven Fallen Feathers and All Our Relations: Finding the Path Forward. She is also the Indigenous-issues columnist with the Toronto Star.

My Parents/This Does Not Belong to You by Aleksandar Hemon

The title of This Does Not Belong to You—one of two books combined into this single volume, which offers a welcome double shot of Hemon—rests on the immigrant’s paradox. The author evokes his past life in Sarajevo, in ex-Yugoslavia: all of it belongs to him, yet it does not, for it is no longer his life, and his country has disappeared. But there is plenty left within him, a powerful mix of comprehension of the past and skepticism of the present, which makes for some great writing.

In My Parents, Hemon does for his parents what he did for his own past, telling the story of how they rebuilt themselves in Canada after the Bosnian War. A typical question when his father met someone: “What bad happened?” His parents came from a land of catastrophe and inhabit it still. As for Hemon, he says of himself: “I am always absent somewhere.”

—David Homel’s latest novel, his eighth for adults and twelfth overall, is The Teardown.

Hymnswitch by Ali Blythe

I find it difficult to explain why I like some collections of poetry more than I like others. There’s always an ineffable feeling when one works for me, similar to how people immediately love certain song lyrics or chord progressions—it can be hard to tell whether it’s because of the sound and rhythm of the words, a particularly tender or intelligent line, a certain playfulness with language, a surprising turn or image. Ali Blythe’s Hymnswitch has all of those things. I kept handing the book to friends, saying, “Read this—it’s so smart.” When I finished the last page, I read it again, which is something I almost never do.

—Zoe Whittall is the author of three poetry collections and three novels. Her latest is The Best Kind of People.

Greenwood by Michael Christie

It’s 2038 and an environmental catastrophe has wiped out most of the world’s trees, creating a planet-wide dust bowl. On Greenwood Island, off of British Columbia, in one of the last old-growth forests standing, Jake Greenwood works as a guide to wealthy eco-tourists. At first, the shared name seems like it could be coincidence. Switchbacking through time and galloping across Canada, Michael Christie unravels the strands of the Greenwood family to answer the question: Does the past dictate the future? A dystopian, historical, speculative, multigenerational family saga, this marvellous, generous book is best enjoyed in a forest.

—Sharon Bala’s debut novel, The Boat People, won the 2019 Harper Lee Prize for Legal Fiction.

The Testaments by Margaret Atwood

Picking The Testaments feels a bit like picking the Beatles as my favourite band or Picasso as my favourite painter—Has there been a more ubiquitous novel in 2019? But it is an essential book for our times. The Testaments is also one of those rare sequels that burnishes the reputation of its predecessor rather than tarnishing it. Through three women’s personal narratives, Atwood charts the rise and fall of Gilead, that theocracy formerly known as the United States of America. The Testaments is not subtle; it’s not even particularly literary. And, for every horror that rings true, there’s another that prompts incredulity. But it’s Atwood at her best—bold, brash, and angry, full of vivid world making, caustic humour, and trenchant critique. The novel considers our capacity to both create and endure a brutal, morally bankrupt society, and the small miracles of imagination, tenderness, and resistance that constitute our humanity when we are otherwise stripped of it.

—Jordan Tannahill is a two-time Governor General’s Award–winning playwright and the author of Liminal.

Your Life Is Mine by Nathan Ripley

I’m one of those reprehensible snobs who has more or less avoided genre fiction. I’d always told myself that there are so many books to read at any given instant, and time is best invested in the literary and/or the highfalutin. This is, of course, a fallacy for lazy readers, and we’re missing out because of it. For those in doubt, I point to Your Life Is Mine, the latest thriller from Nathan Ripley (a.k.a. Naben Ruthnum). And, though I consider Ruthnum a friend and credit our friendship for bringing the novel to my nightstand, it was the book itself that convinced me to reconsider my preconceptions around genre fiction. Ripley’s psychologically deft chronicle of cult secrets and family lies is a master class in plot and a revelation in style. To boot, it’s fun as hell.

—Kelli María Korducki is the author of Hard to Do: The Surprising, Feminist History of Breaking Up.

This Is How We Disappear by Titilope Sonuga

If you are a certain kind of reader, books need to take you by surprise. This happened to me, this year, with This Is How We Disappear by Titilope Sonuga, a poetry collection of bristling imagination and intellect. Sonuga writes her poems from the gravitational centre of the unspeakable atrocities of the 2014 Chibok school kidnapping in Nigeria. From this backdrop, she offers lines that hold what slips from the prevailing social consciousness about girlhood, personal agency in a modern capitalist world, the banality of violence against women, and the precarious conditions of life for children in peril. But it is Sonuga’s facility in welding the lament to the ode to the wonder of the self in the wider context of a possible future that marks the power of her remarkable music and her form-shifting voice.

—Canisia Lubrin is the author of the forthcoming The Dyzgraphxst.

Chop Suey Nation by Ann Hui

When Ann Hui’s deep dive into the origins of the ubiquitous small-town Chinese restaurant first appeared in the Globe and Mail, it felt like a story I’d been waiting my whole life to read. The book-length version, which expands on Hui’s original reporting, delighted me even more. Chop Suey Nation weaves Hui’s cross-country road trip in search of the owners, cooks, and stories behind Canada’s classic “chop suey” restaurants together with an unravelling of her own family’s history. This is a book that thoughtfully explores immigration, familial bonds, and the power of food. I cried more than once, and Hui taught me much about the places and people that I have taken for granted.

—Eva Holland’s first book, Nerve: A Personal Journey through the Science of Fear, will be published in April 2020.