Morgan Harrietha was sixteen when she gathered around the kitchen table with her brother and father to plan for the one thing in life she knew would happen: her death. Three years before, Harrietha’s mother had come to watch her perform at a figure-skating competition. It was like any other competition until suddenly, from across the ice, Harrietha saw her mother slump over in the stands. A stroke. At the hospital, her mother slipped into a coma. Two days later, she was dead.

At forty-eight, Harrietha’s mother had no life-insurance policy and no end-of-life arrangements in place. Her family was forced to guess what she would have wanted. Her funeral, her burial, whether she wished to donate her organs, which keepsakes would go to whom—all question marks. It wasn’t until after the family had already decided to donate her mother’s organs that her health card was found, which listed her as a donor. It was a relief to know that one of her family’s best guesses, at least, was right. Harrietha resolved that she would leave no unanswered questions for the people she will inevitably leave behind.

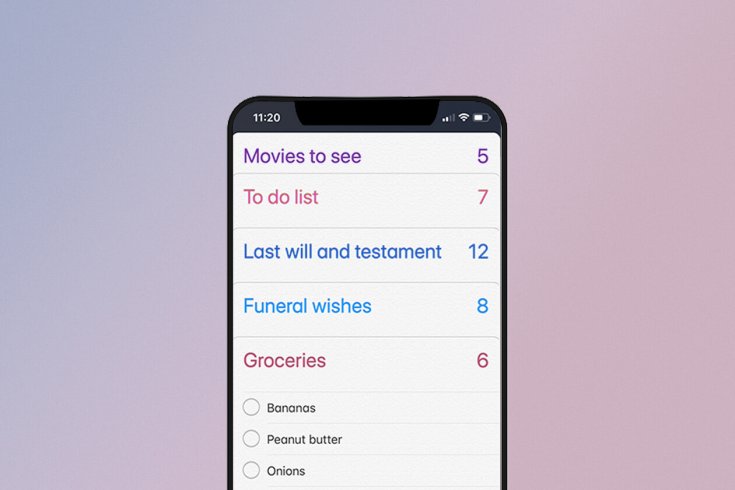

Since that day at the kitchen table, Harrietha, now twenty-one, has made adjustments to her initial end-of-life plans. When I last spoke to her, she was in the process of updating arrangements she made in January 2018 to include what she affectionately refers to as her “zoo”—two Siberian huskies and a cat. She has also had a long-term relationship dissolve and has found love again with a new partner. All those changes will be reflected in her new plans. Today, her last will and testament doesn’t focus on financial or material assets as much as it strives to connect all the dots for the people she might leave behind: how she’d like to be laid to rest, who is in charge of executing specific arrangements, how her digital imprint should be managed.

For instance, she no longer wants to be cremated and dispersed in the ocean. Now, with the environment on her mind, she’s decided she would like to be buried in a biodegradable burlap sack beneath a tree. She’s asked that her brother write a digital obituary for both her Facebook and Instagram accounts. She’d also like him to post a commemorative slide show on both platforms. Instead of announcing her death through the newspaper, her family, Harrietha has said, should announce it on social media. People attending her funeral should leave their black mourning garments in their closets and bring their friendly pets. She wants whoever comes to celebrate her life rather than grieve its loss.

Harrietha is also far from the only young person planning their end-of-life arrangements far in advance. Tim Hewson was thirty-two when he co-founded Legal Wills, in 2000, after he realized how ill prepared he and his friends were: one night while out for after-work drinks, his group realized not one person at the table had a will. He soon left his job at a tech company and cofounded his web service, where clients can pay to have their wills prepared online.

From the start, his main customer demographic has been people between the ages of fifty to fifty-nine. But, within the last decade, Hewson says, the company has also seen a growing number of young, healthy adults—likely far away from death—use the service to proactively plan for the end of their lives. In 2009, only 0.5 percent of the site’s customers were under thirty years old. Now, ten years later, that demographic represents 12 per cent of the site’s users. Faced with the knowledge that, one day, we all must die, these young people have decided to face the end not with fear and trepidation but with control, care, and even celebration.

Like many other industries here and around the world, Canada’s $2 billion funeral business is in the midst of a digital shift toward the world of social media and apps. In addition to online services such as legalwills.ca, a whole host of death-planning sites have emerged in recent years. Everest, which serves both Canada and the US, calls itself a funeral concierge. The company’s main form of advertisement is a YouTube video of a young man named Will who tells the audience he’s dead: “It happens. I’m fine.” American site Everplans, which was founded in 2012, keeps arrangements active for an annual fee of $75 (US).

Then, there are services, like the app SafeBeyond, that are designed to help clients both work through their feelings on death and organize their death-care plans. One option lets a person leave messages and photos for loved ones, which are then posthumously distributed. Another site, Cake, says its goal is to “empower people to live in accordance with their values all the way to the end.” People who have the app WeCroak on their phones are reminded five times a day that they’re going to die. Then there are video games like A Mortician’s Tale. Released in 2017, the game takes players through a day in the life of a mortician. Its goal is to normalize the work of those who care for the dead and dying but also to help address the reality that many of us will end up on a mortician’s table.

Offline, death cafés have become places for strangers to share their thoughts and fears about death. Conversations often range from the practical to the philosophical, and all of them take place in safe and confidential space over tea and treats. The not-for-profit chain has brought together communities across the globe, including in places such as India, Thailand, Bulgaria, and Brazil. Anyone can start a death café in their community so long as they agree to the principles and guidelines on the non-profit’s website. They’re typically run by local volunteers or facilitators who welcome death-curious strangers to literal cafés, apartments, and other venues to ask questions and chat freely about death. Founder Jon Underwood ran the non-profit from its original location in the UK until his sudden death in June 2017. Even so, more and more café locations continue to pop up on the site’s world map, a reminder that death is not always the end.

The popularity of such cafés, apps, online services, and games are all part of the larger, emerging death-positivity movement, which is changing the landscape of death and dying—especially among young people. The movement seeks to reclaim the care of the dying and dead and return it to the hands of individuals and families. Rather than getting stuck in the bureaucracy of big corporations and the funeral industry, death positivity argues that individuals should have an intimate, autonomous relationship with their own death. They should have a say. That means that, at the end of a person’s life, their family will also feel control over the process of both mourning and celebrating—all of it approached with a defiance to the usual painful helplessness that can define a death.

The movement began gaining traction in January 2011 with the emergence of the Order of the Good Death, an organization founded by Caitlin Doughty, a young, Los Angeles–based mortician. Doughty has since become the cocreator of the YouTube channel Ask a Mortician and the author of Smoke Gets in Your Eyes. Her organization has sought to change the morbid or fearful relationship people have with the ideas of death and dying and to encourage people to instead see death as a natural, inevitable part of life. We didn’t, after all, always feel this way about death.

Before the twentieth century, in the West, funerals were arranged by families and neighbours. Funerals were intimate. They were held at home. Although community graveyards existed, people were often buried on family property. As populations grew, funeral homes emerged to relieve families and communities of the logistical elements of caring for the dead. But, in removing ourselves from carrying out these tasks, advocates like Doughty say, we made death taboo. We stopped talking about it. We started to fear it more. It became morbid. It fell away from the regular rhythm of our lives and into the abstract. We disconnected ourselves from a fundamental truth of being human. Now, in 2019, we’re furiously trying to reconnect with death to better understand it. In so many ways, though, what we’re really trying to do is understand ourselves.

In December 2009, Cassandra Yonder was working as a grief counsellor in St. Ann’s Bay, a rural community swathed by thick woods in Nova Scotia, when a friend of hers died. She arrived at the family’s home to find her friend’s wife, cradling him in her lap while waiting for his body to be collected by the coroner’s transport team. While there, Yonder watched his wife say goodbye to her partner with surprising grace. She spent the next five hours by her side, witnessing something she described as being similar to a home birth: her friend leaving the world in an intimate setting, his home, in the arms of a loved one.

The experience, and her work as a grief counsellor, transformed her ideas about death and dying. Previously, when she’d think about death, she’d picture almost cliché images of groups of people dressed in black gathered around a dead body caked in makeup and pumped with formaldehyde, resting inside a coffin. But the experience with her friend truly showed her how exiting life could be embraced with the same compassion, respect, and celebration as being born. Soon after, Yonder began her full journey into the death-positivity movement or, as it is also known, the community death-care movement. She trained at Final Passages Institute of Conscious Dying, Home Funeral and Green Burial Education, a non-profit organization in the US, specializing in alternative funeral and death practices. Yonder emerged from the institute as a death midwife (also known as a death doula). She now considers herself a community death-care educator, someone who teaches ordinary people how to care for their own dying family members.

In much the same way a birth doula or midwife supports women during labour, a death doula or midwife supports people in the process of dying. Today, Yonder likens the death-positivity movement to the slow-food movement, which aims to preserve regional food sources by encouraging the farming of plants, seeds, and livestock characteristic of the local ecosystem. It also champions the reclamation of food production from the corporatized mass assembly lines that make the food most of us consume. Just as many people are disconnected from the process that brings their grocery products to the store, they are also disconnected from death and dying.

Many people do not care for their dying and the dead, explains Yonder. Loved ones often die in hospital beds and are then transferred to a morgue before they are taken to a funeral home. Like the millennials who find comfort and control in determining the details of their final days and beyond, Yonder is working to help reconnect families with death and place them back at the centre of their own experiences. For her, that means reconnecting to the process of grieving. It also means greener, more intimate, and less costly burials. Families who take part in funeral planning and those who decide on home funerals, she adds, often navigate grief with a healthier mindset and are able to better relate to the person who has passed. “I think people are going to funerals and having this same response, this weird disconnection,” she says. “We’re realizing we are putting our aging, our dead, out of sight and out of mind.”

In the end, that is what this new movement is all about: connection. For some, that means planning their end of life with as much care as a they plan for the beginning of life, for births. For others, it means sitting down in death cafés or installing an app on their phone. For millennials like Harrietha, that connection means figuring out how death fits into their lives now. Most of her friends are under twenty-five, and although conversations about death don’t yet happen regularly, she’s noticed they’re now more willing to discuss the topic. She says watching her friends trying to figure out and accept the intricacies of death is like watching them pick up a ball and turn it over in their hands. Over and over. They chuck it across the room to see how hard it will bounce back. They bring it up close and inspect it with fear and curiosity in equal measure before setting it down. She knows they’ll pick it back up. She suspects many of them will have an end-of-life plan in place by the time they’re thirty.

As a society, we’ve thrown the ball across the room. We set it down, handed it over to a thriving funeral industry, we stopped feeling comfortable talking about it, we removed ourselves from the processes of grieving and dying. Increasingly, there is an urge to hold it in our hands, to see what the ball is made of, and to see what we can do with it. As we pick the ball back up, we may just discover how death shapes us and connects us as human beings. We may discover that endings can be beautiful too.