Most weddings are attended by a few sulky guests. And every wedding produces some very stressed-out hosts. But the celebrants at a wedding I was at recently in Bangalore weren’t worried about the quality of the food or the bride’s dress. In fact, people hardly talked about the wedding. After polite exchanges, the conversation usually turned to war: Was there just cause after Mumbai? Was the nuclear option on the table? And were those fighter jets flying over our heads on a routine exercise or headed for Pakistan?

Gathered on the coconut tree–lined lawns of the posh hotel were the groom, a Muslim from Pakistan, the bride, a Hindu from Calcutta, and the guests, a mixture of Indians and Pakistanis who looked at one another with cautious optimism. They invited one another to their hometowns and exchanged email addresses, wondering all the while whether they would ever meet again. The bride’s grandmother, watching the ceremonies from a quiet corner, broached the subject wearily. “There won’t be a war,” she told the Pakistani bridegroom. “Your country has already lost three wars with India.”

India-Pakistan marriages are rare but not unheard of. In my experience, they are usually arranged between families who were divided at the time of partition. In an attempt to maintain ties, girls are dispatched to India and vice versa. But over the past decade, I’ve heard more and more of another kind of marriage, usually between young people who have met at film festivals, ngo forums, Western universities, or, in some cases, in Internet chat rooms.

The portly pandit performing the ceremony pretended that the Muslim guests were all Hindus. I, for example, sat in the mandap, a canopy of real and plastic flowers, as he pressed marigolds, uncooked rice, and seashells into my hand. He continually exhorted us to give him more money to please the gods. I obliged. He read out an eight-point code of conduct for the married man from a tattered Sanskrit manual, explaining the concept of fidelity for men, beautification for women, and financial prudence for both (foolish is the man, he said, who buys a cow when he is not even able to tend to the one he already has). He told the bride and groom they must always do their puja rituals together. “They should probably make sure they go to pubs together,” someone quipped.

Next morning, I woke up in my serviced apartment to the thunder of fighter jets flying very low in the sky. On the local news, a succession of retired Indian generals spelled out plans to teach Pakistan a lesson. The last one, who seemed to have been ordered in from central casting, complete with a twirled-up moustache, cautioned that India should only use nuclear weapons as a last resort.

I went online to find out what was happening in Pakistan, as there are no Pakistani news channels in India. It was a similar story there: jets flying over major cities, while my fellow citizens spilled out onto the streets to cheer them. The alleged father of Pakistan’s nuclear program, Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan, who has been under some form of judicial restriction ever since pleading guilty to midwifing nuclear weapons programs for Libya and North Korea, was reported on one site to have issued a statement: “I’ll forget my disgrace if I am given the opportunity to press the nuclear button.” I am not sure what scared me more — the offer or his nonchalance. He came off like a disgruntled uncle who will only come to the wedding if he is seated beside the bridegroom.

The strange thing, given the heated rhetoric, was that since arriving in India I hadn’t seen any signs of a country preparing for war. When the immigration officer at the New Delhi airport asked for my passport and then for my permanent address in Pakistan, I steeled myself for his reaction. Several of the Mumbai attackers who brought the subcontinent to the brink of nuclear confrontation less than a month earlier had allegedly come from my hometown, Okara. But he stamped my book and ushered me into India without a second glance. Security officials were mainly concerned about the consumption of alcohol on my domestic flight, confiscating a bottle of gin I was carrying. And once I reached Bangalore, a sandbag bunker outside the black marble and steel airport — the only reminder of these troubled times — looked more like a piece of conceptual art.

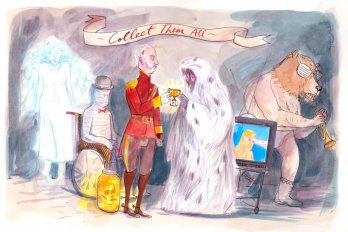

By the time I was on my way home four days later, war hysteria had reached fever pitch in the media, but not much had changed at the airport. A lone soldier wearing full military fatigues and cradling an automatic weapon put me in mind of a tired corporate mascot. He scanned the passengers saying their teary goodbyes, unable to tell the Indians from the Pakistanis, then leaned back against a pillar and rested.