When Luc Bourdon’s feature-length film, The Memories of Angels, was screened last fall at the Toronto International Film Festival, audiences sat in awe of the stunning collection of images of Montreal. There were shots of Parc Lafontaine in the summer, ships docked in the Old Port, and revellers taking in a Paul Anka concert. The film received rave reviews, and the National Film Board, the government’s storied film-producing institution, which turns seventy this year, touted it as another cinematic success.

The film is an intriguing artifact. In making it, director Bourdon did not once employ a camera, nor generate any new images (beyond the credit sequence). Along with an editor, he pored over the nfb’s massive archives and chose hundreds of shots from previously made films from the 1940s through the 1960s, stitching them together to create a montage that is equal parts love letter to Montreal and ode to the nfb’s considerable achievements.

The Memories of Angels, like another recent nfb film, the Oscar-winning animated short Ryan, looks back at nfb history. Memories is a reconfigured collection of shots from films by such masters as Denys Arcand, Arthur Lipsett, Michel Brault, and Claude Jutra. Ryan is an exploration into the work and life of the Oscar-nominated filmmaker Ryan Larkin, a former wunderkind who was found, a quarter century after his work had essentially stopped, homeless and broken. These films’ success begs an obvious question: is the nfb an institution that has nowhere to go but to look back to the glory days of its golden age?

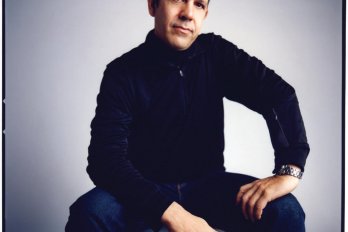

Not surprisingly, the nfb’s new commissioner, Tom Perlmutter, takes umbrage at the suggestion. Ushering me into his office at the nfb’s Montreal headquarters, he makes the distinction between empty nostalgia and creative renewal. “It’s interesting, to me; that’s precisely the way not to be a slave to the past. Those films are an hommage, and they’re both entirely original in their own ways. The editing in The Memories of Angels is amazing — it’s a tribute both to the city and to the history of filmmaking. It’s not simply a recycling, but rather a reimagining of those images.”

Like every other commissioner for the past couple of decades, Perlmutter, who took over the job in June of 2007, understood he would have to justify the nfb’s existence. He already had some related experience: since 2001, he had worked as director-general of the board’s English programming. Before that, he amassed considerable credits as a film producer, working on such series as Turning Points of History, The Sexual Century, and The Body: Inside Stories. During his tenure, Perlmutter became an unofficial ambassador for the board, talking up its record across Canada and abroad.

The nfb, of course, holds an entirely unique position in the national cinema landscape. Unlike Telefilm, which offers government subsidies to privately funded movies and is seen as a way into the potentially profitable world of theatrically released features, nfb films, which are primarily documentary or animated, are often experimental in nature and not made with profit in mind. They are non-commercial, and while there may be economic spinoffs associated with their production and distribution, they’re not expected to become blockbusters.

If defending the nfb is a familiar role for the person in Perlmutter’s job, it’s also an odd one. Put it this way: if you were a headhunter and the nfb were a candidate looking for a job, you’d hire that person in a nanosecond. Since its founding in 1939, the nfb has raked in a litany of awards (over 5,000), including twelve Oscars, citations at every major film festival in the world, and praise for its library from a legion of prominent filmmakers. George Lucas credits Arthur Lipsett as a major inspiration; Quentin Tarantino cites the wondrously strange 1996 documentary Project Grizzly as one of his favourite films of that year; and when I interviewed Gus Van Sant about the history of his life and work, he cited watching nfb films while in school as a formative experience. Thus the strange paradox that haunts the nfb: it is famous and revered in the international film milieu, while infamously obscure on its home turf.

I recently conducted an entirely non-scientific survey, which confirmed my impression that not only do many (if not most) Canadians not get the nfb; they’re not even sure what it is. At one of Montreal’s busiest downtown intersections, the corner of Peel and Ste. Catherine, I stopped ten passersby to ask them two simple questions: what is the nfb, and can you name an nfb film? Five drew a blank; one guessed that the nfb was a financial institution; four correctly identified the nfb, but only three could name an nfb film. A small sampling, certainly, but the results are telling.

It is precisely this obscurity that has allowed successive governments to cut the board’s budget, curtailing its creative reach. While there have been various nips and tucks over the decades, the cruelest and most epic came in 1996, when the Liberal government made eradicating the federal deficit priority number one. The nfb’s government allocation was slashed by a whopping one-third, meaning it received around $65 million a year.

The nfb was now in a very difficult position. It had less money to work with, but sensed that if it didn’t produce real evidence that it was reaching bigger, broader audiences, its funding could be cut even more radically. So it did what any exposure-starved film-producing organization would have done in the mid 1990s: it shifted its emphasis to television. If more nfb films found audiences on TV, it could vastly extend its reach and thereby prove its relevance to the Canadian public.

That was the theory, in any case. In practice, the strategy was almost catastrophic. The nfb had had a fraught relationship with broadcasters since the 1960s, when it began making more daring forays into social-issue filmmaking. In a pre–Michael Moore world, many of them viewed the board’s films as overly personal and biased. In 1982, for example, Montreal filmmaker Terre Nash made If You Love This Planet, a short documentary that captured the lecture of no nukes crusader Dr. Helen Caldicott. The film was branded propaganda by the Reagan administration, a view shared by the cbc, which refused to screen it on the grounds that it didn’t show both sides of the argument. (Caldicott questioned this critique, saying that they’d have a hard time finding someone in favour of nuclear war.) Eventually, the film won an Oscar, and the cbc, bowing to pressure, had a change of heart. Four years later, in 1986, the nfb produced the documentary miniseries Reckoning: The Political Economy of Canada, an examination of our business and political relations with the world, particularly our main trading partner, the United States. Again, the cbc refused to screen the series, citing its bias. This put many Canadians, whose tax dollars paid for the production, in the odd position of having to tune in to pbs to see it.

The publicity surrounding these controversies only added to the sense among more conservative Canadians that, as one of my right-leaning friends back in Alberta put it, the nfb is merely a “lesbian communist daycare centre for people of colour.” And Perlmutter now admits that trying to force the nfb’s films into the more conservative template of television was a mistake. Broadcasters could and would dictate aspects of content and production. Filmmakers were pushed to conform to the standards of the medium. “The question then was, how do we reach our audiences? It seemed the only way was through television. But being on TV was damaging to the nfb, because we disappeared. We were lost amid the range of products. The nfb was always about doing things the private sector cannot do. The broadcasters are important partners, but they can’t be the be-all and end-all.”

Everyone agrees that the nfb’s main strength has been its ability to take risks. Some of its most-praised films, including the controversial poverty exposé The Things I Cannot Change (1967), If You Love This Planet, and the Academy Award–winning I’ll Find a Way (1977), were made by novice filmmakers. But taking risks can be expensive, which is why some insiders feel that, even with stalwart leadership, occasional awards, and praise from abroad, the nfb is doomed to irrelevance. “I just don’t think we have the money to be cutting edge and risky anymore,” says one senior producer. “You have to allow for some failures, and if you have only twenty projects you can independently fund every year, that doesn’t leave you a lot of room for taking chances. In my experience, the craziest ideas are the ones that end up making for great movies. How can we even think about crazy ideas when the nfb is so seriously strapped for cash?”

Even Perlmutter, still relatively new at the job, has had to resort to cost cutting, something he views as ugly but unavoidable. In June, it was announced that twenty employees would be let go, among them two of the nfb’s most prominent staffers, Paul Cowan and Beverly Shaffer. (Shaffer won an Oscar in 1978 for I’ll Find a Way, her crowd-pleasing portrait of a young girl living with spina bifida.) The plan drew sharp criticism from many at the board, who felt Perlmutter was betraying their trust, and the best interests of staff. “We’ve had no increase to our allocation for years,” Perlmutter says. “We have been in financial decline simply because costs have gone up, which has meant a significant loss in purchasing power. We have to use our operating budget in the best ways we can.” The cuts generated a series of not terribly favourable headlines, like the one that appeared in the June 9 Montreal Gazette: “National Film Board Is Being Starved into Submission.”

Still, Perlmutter insists that the nfb remains vital and relevant: “We’ve made the economic arguments for the nfb in the past. I think we have to move beyond that. We’re in a country that’s one of the great social experiments. How do you create a post-nation-state civil society founded on common social values while still respecting diversity? That demands dynamic exchange, and the film board excels at that. We’ve given voice to a number of communities that were previously voiceless.”

Despite the failure of the television initiative, Perlmutter is now looking to another medium to make the nfb more accessible. Some of the savings from the June cuts will pay for the digitizing of over 500 films from the nfb’s library, all of which will be put online this year. “The cinema has always been about artists using new technologies,” Perlmutter says. The irony is a rich one: while most in the film industry’s private sector are panicking about what the Internet will mean for their profitability — daunted by the apocalypse that has already swept through the music and newspaper industries — some see online streaming as a logical distribution route for the nfb, where making money isn’t necessarily the main goal. “This will be crucial in creating a better sense of brand awareness,” says Perlmutter. “If people can actually get at the nfb films, I think that will make a real difference.”

In September, one of the nfb’s co-productions, Examined Life, premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. The film is an entirely unique meditation on the thoughts of some prominent philosophers, including Cornel West, Martha Nussbaum, and Judith Butler. After the screening, during a Q&A session with the audience, filmmaker Astra Taylor marvelled at the nfb and the freedom she was granted while making her documentary. “I don’t know where else in the world I would have been able to make this film,” she said enthusiastically. The audience burst into applause.

The nfb has won the support of a group of Toronto philosophy enthusiasts. Now, if only it could reach the other 99.6 percent of the Canadian population.