books discussed in this essay:

The Castle in the Forest

by Norman Mailer

Random House (2007), 496 pp.

Why Are We At War?

by Norman Mailer

Random House (2003), 128 pp.

Point to Point Navigation: A Memoir,

1964 to 2006

by Gore Vidal

Doubleday (2006), 288 pp.

Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace: How

We Got To Be So Hated

by Gore Vidal

Nation Books (2002), 160 pp.

Behold the lions in winter. Norman Mailer, now eighty-four, has recently published The Castle in the Forest, a 496-page novel that analyzes the childhood of Adolf Hitler and is narrated by a devil. In 1998, he published The Time of Our Time, a 1,286-page anthology of his work. In the last several years, Gore Vidal, eighty-one, has published The Essential Gore Vidal, a 988-page compendium of his essays, novels, and theatre work, as well as a collection of short stories, a form (perhaps the only one) he isn’t known for, and Point to Point Navigation, described in the dedication as a “final memoir.” Over the last sixty years, Mailer and Vidal have produced millions of words, made hundreds of television appearances, launched three unsuccessful political campaigns (Vidal for Congress in 1960 and for the Senate in 1982; Mailer for mayor of New York in 1969), and had one celebrated fist fight, accounts of which, unsurprisingly, differ markedly. Their recent books, however, have the quality of epitaphs.

It is not just their own passing that is being anticipated in these books, or the novel’s, which has been said to be dead for nearly as long as it’s been alive. Vidal wonders where his books will be half a century from now. He has been critical of university English departments and is not found on reading lists with great frequency. Though, as he dryly notes, “If you miss one syllabus, there’ll always be another in the next decade.” Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead was on my American Literature course list in the 1970s. A check of the same list today finds him replaced by Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried. Edith Wharton and Ernest Hemingway still hang on.

The novel is surviving quite handily, it turns out, but the novelist isn’t faring as well, at least as public figure. Even the mystique of the Salinger/Pynchon model of never actually appearing in public is waning (though the famously reclusive Cormac McCarthy made an appearance on Oprah). The whereabouts of any novelist are moot. I wasn’t aware that Philip Roth was a recluse until I read about him in the New Yorker. Novelists are all in hiding these days, none more hidden than those who are out there shilling their work, reading in small (occasionally empty) rooms, appearing unperkily on Breakfast Television.

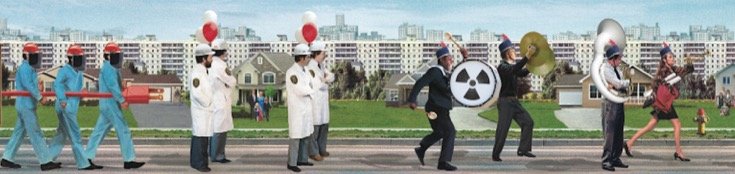

The death of the novelist as public figure might not be a bad thing, but what they have been replaced by isn’t cheering. Talk shows were once home to writers like Truman Capote, Gloria Steinem, Saul Bellow, Mailer, and Vidal. A short chapter of Vidal’s memoir is devoted to Johnny Carson, as Vidal was a frequent guest on his show, as well as on Merv Griffin, Today, and Dick Cavett. Talk shows are less amenable to authors these days, unless they are promoting cookbooks or diet books or self-help guides. Mailer and Vidal pronounced on political and cultural matters, which are becoming abstractions, and TV isn’t well suited to ideas. It is happiest with manufactured conflict or punchlines. Public intellectuals have given way to comedians like Jon Stewart and Rick Mercer, who discuss politics on TV and have better timing. Today, public debate exists within a framework of recognizable entertainment.

In his journalism, Mailer embraced the idea of the literary artist at the centre of current events (sometimes to a fault). It is what animated his political writing, most of which retains its vitality. The Armies of the Night, which described the March on the Pentagon, won a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award, and Miami and the Siege of Chicago reported on the Republican and Democractic conventions of 1968. Both books enjoyed a large audience. Mailer’s most recent political book, Why Are We At War? (2003), had little impact. Parts of it appeared first in speeches and interviews, and the 128-page paperback version reads like an afterthought. It doesn’t have the visceral and reportorial energy of Armies or Miami, but then there is little to report on in the current climate. Demonstrations are small, localized affairs these days, and political conventions are produced as television shows. Despite high production values and celebrity endorsements, they have failed to find a large viewing audience, another sign of disengagement.

In Why Are We At War? Mailer writes, “In a country where values are collapsing, patriotism becomes the hand-maiden to totalitarianism. The country becomes the religion. We are asked to live in a state of religious fervor: Love America! Love it because America has become a substitute for religion. But to love your country indiscriminately means that critical distinctions begin to go. And democracy depends upon these distinctions.” Debate has become less spirited in America, and this isn’t just because dissent is considered treasonous in certain quarters. Apathy is the bigger problem. There is little audience for critical distinctions or even for democracy. There won’t be any more Armies of the Night, unless they’re heading for a midnight madness sale at Wal-Mart.

Despite his recent public appearances, Vidal, too, is less of a political force these days. His latest essays are still trenchant, his wit intact, but his piece on 9/11 was turned down by his usual outlets, including The Nation, where he is a contributing editor. In-stead it became a short book that was sold internationally but not in the US. The polemic was eventually published in a paperback collection of essays, Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace: How We Got To Be So Hated (2002), by a small American press. In it, Vidal examines the reasons for 9/11 and for Timothy McVeigh’s bombing of a federal building in Oklahoma City, which killed 168 innocent people. Vidal looked into McVeigh’s political motives, an unpalatable examination, but the unexamined democracy isn’t worth having, to paraphrase Socrates. It is more comforting to think, as President Bush continues to, in terms of good and evil, which despite his Christianity he presents as cinematic values rather than Biblical ones. They are a staple of the small and large screen, the simple verities that fill seats.

While Bush personifies the government’s retreat from democratic principles, he isn’t alone among US presidents. Vidal notes that it was Bill Clinton who signed into law the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, which, among other things, weakened habeas corpus. In his essay “Truman,” Vidal vilifies Harry Truman’s administration, writing that, under his watch, “the American Republic was quietly retired and its place taken by the National Security State.” The end of the Republic and the beginning of Empire. As an essayist, he has few peers. His voice is droll and erudite, a comfort. In his eleven collections, Vidal outlines how the country has gone from democracy to oligarchy with little fanfare, beholden to corporations.

Democracy needs a viable electorate, and it also depends upon a collective historical memory. Engendering this has always been a hard sell. People tend to be complacent about freedom until it is seriously compromised. Then they rebel. But there is a wide territory in the middle, which we seem to be occupying. Perhaps this is why Mailer and Vidal felt compelled to write so many historical novels: to remind Americans what is at stake.

Mailer’s Oswald’s Tale (1995) dealt with one of America’s central political mythologies, the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Harlot’s Ghost (1991) was a 1,310-page examination of the cia, a metaphor for the duality of America: on the one hand, a giant, benign International House of Pancakes; on the other, a sinister international bully. The book ends with the words, “To Be Continued.” The story has been continued, though not happily; the cia pursues its grey mission with mixed results.

Vidal’s historical novels (among them Burr, Lincoln, 1876, and Empire) are more conventional than Mailer’s: fat, elegant books that are gently prescriptive. He devoted a great deal of literary energy to setting the record straight. At times Vidal the essayist is heard in these novels, usually a welcome moment. When his third novel, The City and the Pillar, was published in 1948 with its homosexual theme, America was publicly chaste and virtuous, and Vidal was viewed as controversial. Now it is America that is controversial, and the atheistic, pan-sexual Vidal has become the calming voice of morality, democracy, and reason.

Imagine Margaret Atwood stabbing her husband, lobbying for the release of a convicted murderer who is then released and kills again, running for mayor of Toronto on the platform that it separate from the hick province that surrounds it, and appearing on The National, visibly drunk, telling Peter Mansbridge that Alice Munro lacks the balls to write long. This was Mailer at his most Maileresque.

In his contemporaneous novels, Mailer was able to capture the rhythm of a place through language, whether it was the menace of Harlem in An American Dream (1965) or the menace of Texas in his stylized, stream-of-consciousness dialogue in Why Are We In Vietnam? Certainly, menace is a fixture. If Vidal is America’s most articulate critic and its curiously attenuated conscience, then Mailer is America itself: ambitious, excessive, violent, expansive, and a sucker for self-mythology.

Mailer’s first novel, The Naked and the Dead (1948), was a huge success, and, at the age of twenty-five, he was immediately famous. His second, Barbary Shore, was panned as immoral, making him infamous. What better combination for a young writer? His third novel, The Deer Park, met with tepid reviews, and uneasiness set in.

America was his subject, and when he stepped outside its generous bounds (and outside the contemporary), he was on less sure ground. Ancient Evenings, The Gospel According to the Son, and his most recent book, The Castle in the Forest, are a curious combination of daring and ponderousness. There is a palpable, occasionally oppressive ambition in these books. Ancient Evenings is set in ancient Egypt; The Gospel According to the Son tells the story of Jesus in the first person; The Castle in the Forest is Hitler’s youth narrated by a devil. All of them are long. Mailer’s historical works are towering in the way of a stranger’s genealogical tree, a discouraging web of aunts and precedents. They also limit his greatest gift — language. The awkward, broadly vilified Bible-speak of The Gospel According to the Son is stilted, perhaps necessarily so. But Mailer’s is a relentlessly modern voice, and reading his historical work is like watching a boxer use only his left jab throughout a fight.

Mailer has been most interesting and most effective as a journalist, especially if his true-life novels like The Armies of the Night and The Executioner’s Song are included on the list. The form imposed parameters on his work but allowed his language, which is opulent and muscular, free rein. His two greatest subjects were America and himself, but now his country appears to have a waning interest in both.

Vidal began his career with Williwaw (1946), a modest success, and in the next four years there were four more novels, including The City and the Pillar (1948), which described the odyssey of a gay man and was predictably scandalous. When he published Myra Breckinridge (1968), the satirical story of a transsexual who hates men, it was also scandalous, but by then the public was embracing scandal, and it became a bestseller. Myra Breckinridge was also made into a desperately campy film, with Vidal listed as one of the screenwriters. He wrote thirty or so teleplays in the 1950s and has occasionally appeared onstage and in films. Television is his second home (“Never pass up an opportunity to have sex or appear on television,” he once remarked), and film is a fixture in his life. In his new memoir, the opening line is, “As I move, graciously, I hope, toward the door marked Exit, it occurs to me that the only thing I ever really liked to do was go to the movies.”

Film seduced Mailer as well. He starred in and directed three experimental movies and played an architect in Milo Forman’s Ragtime. As writer James Baldwin noted of Mailer, “One of the irreducible difficulties of being an American artist lies in the peculiar nature of American fame. . . . It’s very difficult . . . not to become show business.” That was then. Both Mailer and Vidal embraced show business. They drank with celebrities and wrote of celebrity (Mailer’s biography of Marilyn Monroe, Vidal’s Hollywood essays). They sought fame, rolled in it, ate and shat it.

Now, of course, show business has pitched its tent among the hoi polloi. Reality has overtaken us all, and, in the extended YouTube of modern life, writers have become peripheral.

Vidal argues that the category “famous novelist” no longer exists, that it has become as abstract as “famous speedboat designer.” He writes, “How can a novelist be famous — no matter how well known he may be personally to the press — if the novel itself is of little consequence to the civilized, much less to the generality? ” What has replaced novels, in terms of what is being discussed in the agora, is, of course, movies. Vidal writes that Francis Ford Coppola was the first “film generation” person he had met. “For him the written culture had passed into the night.” Vidal’s sense of the demise of the serious novel, and with it, literary fame, is a consequence of the loss of history.

It is hard for any artist to hold a large audience for a long time. Readers tend to fade or forget or move on to other things. That Vidal and Mailer held court for sixty years is remarkable in itself. The modern audience is less engaged, it lacks the energy for debate. Perhaps there is a new force gathering among the blogs and Facebooks out there, an Athenian model that will raise participatory democracy to a new height. In the meantime, there is Oprah. Mailer is right that critical distinctions have fled. What remains is complacency, a comfortable and dangerous territory. That Mailer and Vidal will take their particular brand of fame with them when they go is cause for lament. That they will take a piece of history with them is cause for concern.