Those who encounter Tobias Wong’s work often waste their breath debating whether he’s an artist or a designer when there’s one label that’s perhaps more fitting: troublemaker. Working from New York, the Vancouver-born Wong is famous for lapping up tidbits of consumer culture, merging them with the work of other artists and designers, and expelling it all in his own meticulously crafted creations. One of his earliest pieces, named This Is a Lamp, involves a plastic Bubble Club chair by French designer Philippe Starck that Wong reconfigured with a light bulb and pull cord and then premiered one day before the release of Starck’s own chair in New York. In response to Karim Rashid’s book I Want to Change the World, he carved the shape of a handgun from its pages and left viewers to decode whether the piece was a call to arms or a tool for suicide. Shortly after 9/11, he developed a special box cutter — a luxurious chrome-plated model engraved with the words “another notion of possibility.” More recently, he and artist Amelia Bauer created a chandelier for Swarovski, called the Iceberg Chandelier, that was released during the Art Basel Miami Beach fair last December. Consisting of an aquarium filled with crystals and piranhas (acquired on the black market because the fish are illegal in Florida), it was a biting comment on the fair itself.

Wong is, quite literally, a shit disturber: he has even created ingestible capsules filled with silver leaf that are intended to make a user’s feces sparkle. This example effectively illustrates one of his favourite targets?—?conventional notions of luxury. He has produced crystal chandeliers coated in white rubber, pearl earrings dipped in black rubber, gift wrap made with original Andy Warhol screen prints, and a ring where the diamond is hidden on the inside of the band. But interpreting Wong’s objects as out-and-out attacks on luxury goods would be a mistake. After all, he admits to lusting after the extravagant objects himself. “We all have this desire for having the best of something,” he says. “But we’ve gotten to a point where you’re not really even appreciating the object. Pearls, having them rubber coated, leaves you as the only person who knows what you have underneath. There’s something nice about having $5,000 earrings on. There’s something even better about knowing that you’re the only one who knows.”

And he was ecstatic when the clothing and accessories design house Burberry copied his own ripoff of the company’s tartan. Because Burberry was notorious for rabidly defending its exclusive ownership of the telltale plaid, Wong decided to confuse matters by buying a Burberry shirt, cutting it up, and making his own pin-back buttons with the material (and later, with photocopies of the material). Who owned the tartan then? Hipsters in New York went crazy for them, and the buttons were soon being paraded through city streets affixed to hundreds of bags and jean jackets. But rather than suing Wong, Burberry stole the idea back and put the buttons in its ads. The pleasure of having Kate Moss promote his creations was something Wong had never dreamed of.

Wong’s body even bears physical evidence of another heist. At a gallery opening in 2002 he asked conceptual artist Jenny Holzer to write something on his skin, and she scrawled her famous mantra “Protect me from what I want” on his forearm. It was precisely what Wong wanted. He ran to the nearest tattoo parlour and claimed the phrase as his own, permanently inking it into his flesh.

“That bad-boy phase is gone, hopefully,” Wong tells me when I meet him at the Bound and Unbound gallery in New York. He has been quietly paying his dues here for the past six years by assembling works from Fluxus, an anti-art art movement founded by George Maciunas in the early 1960s. When Maciunas died in 1978, he left behind piles of material and instructions for unfinished projects. Wong took up the task of completing them. One of his favourites is A Box of Smile by Yoko Ono — a simple cube of black plastic with a mirror on the inside that has a knack for making people grin.

Painstakingly assembling thirty-year-old art projects certainly doesn’t mesh with the bad-boy reputation, and neither does Wong’s demeanour. He is short, sprightly, clean-cut, friendly, and extraordinarily polite. Besides the Holzer tattoo, the only other hint of subversion is a tiny square tattoo on his chin, which could be mistaken for a mole. It’s actually a memento of the three years he spent in the University of Toronto’s architecture program before dropping out to study sculpture at the Cooper Union in New York. “I was really into the modern square,” he says. “And Ithought if I could end it right there and then, I could start doing everything else. That was a milestone?—?being able to walk away from architecture more than halfway through.”

But that wasn’t the end of his soul searching. In 2004, at the height of his popularity but nonetheless feeling that he was in a creative rut, Wong announced his retirement from art and design, claiming he would return to Vancouver to begin a career driving trucks. “I was getting a little tired of hearing myself,” he says. “I had enough examples of where I was coming from, and it got to a point where people just wanted to see more of the same thing. And that really was a problem.” He decided that if he didn’t have anything new to say, he wouldn’t say anything at all.

Of course, since I’m sitting in a Manhattan gallery, flipping through a portfolio of his latest work when he tells me about all this, the whole notion of retirement is a little difficult to swallow. But when I suggest that it was only a joke, he pulls out a photo to demonstrate just how sincere he was?—?the shot shows the self-described “tiny little guy” in the seat of a transport truck, clutching the top of a monstrous stick shift. He hasn’t earned his licence just yet but says he did take lessons out West and still plans to return to trucking someday. And even though he has taken up art and design in New York once again, he hasn’t produced any solo work since the retirement announcement, choosing to focus on collaborative projects instead.

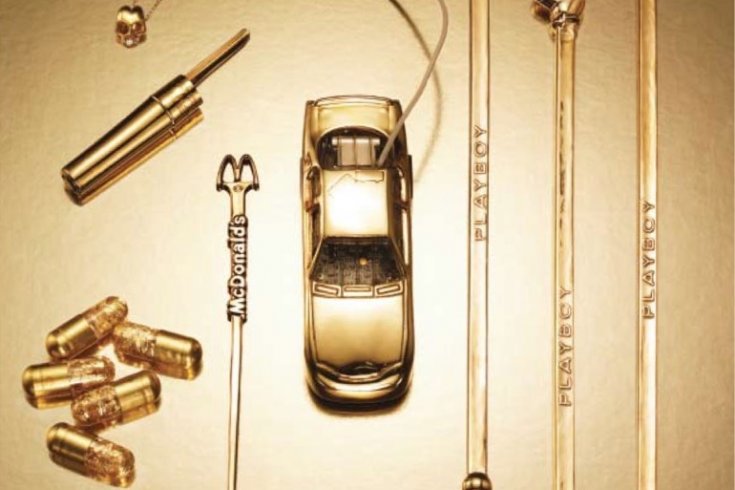

Still, his touch is readily apparent in his latest creations. With Ken Courtney (a.k.a. Ju$t Another Rich Kid), he recently designed the Indulgences line?—?everyday objects dipped in gold to make them more precious, including Bic pen caps, toy cars, and Playboy stir sticks. With Niels Bendtsen, a veteran furniture designer in Vancouver, Wong has created the Pentagon sectional sofa, which can be put together in the same shape as that fortress of US military power. When people kick their shoes off to dive inside, the footwear creates a pile of rubble, just like the one at the real Pentagon five years ago.

It’s this play between humour and serious commentary, realized through brash, smart-alecky gestures, that characterizes Wong’s best work. “Object after object, they always have a sense of humour and a lot of irreverence, and sometimes even anger in them,” says Paola Antonelli, the architecture and design curator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art who recently selected a couple of Wong’s pieces for an exhibition called Safe: Design Takes On Risk. “I like them for that reason — because they’re very delicate and very brutal at the same time.” Wong’s Ballistic Rose Brooch, which was one of Antonelli’s picks, is a perfect example. Featuring a flower made from black, bulletproof nylon, and an underlying promise to protect a wearer’s heart, the object is pure poetry.

Wong has invented a few different terms to describe his work. He drops words like “postinteresting” and “readydesigneds” every once in a while when discussing his pieces, but the main one he likes to use is “paraconceptual.” Against the pretensions of high conceptual art, Wong started making work that clearly had a double purpose. He created pieces that could be considered art or just as easily be marketed as straight-up consumer goods. His Starck lamp is a good example: “It’s very conceptual, but at the end of the day, most of the viewers just say ‘Wow, that’s a beautiful lamp.’ ”

The piece was intended not only as a tribute to Marcel Duchamp, who famously called a urinal Fountain and deemed it a work of art, but also as a proposal to reset the clock on conceptualism. “I thought if I could start at the beginning of conceptual art and turn a chair into a lamp by saying ‘this is a lamp,’ then we could start the dialogue all over again,” says Wong. The piece is also one of his readydesigneds — a design object he has reinterpreted for his own purposes, and an idea obviously borrowed from Duchamp’s readymades.

But where Duchamp’s readymades were often crude, seemingly thrown down in galleries with reckless abandon, Wong teases people with carefully crafted beauty. His pieces typically have a flawless finish, like the luxury goods they question. You could be excused for lusting after his take on Commedes Garçons perfume, for which he marinated diamonds, or for Graffiti Bottle, for which he covered the back of another perfume vessel with an even, black-matte surface into which people could carve personalized messages.

It is for this reason, and the fact that some of his objects end up being commercially produced, that critics are sometimes unsure where to place his work. Is it art or is it design? His wares are sold at retail stores, he consciously stays out of most galleries, and he usually participates in design fairs instead of art fairs. “If you want a piece to work, it has to be within its context,” says Wong. “A lot of the pieces I make that look like design objects need to be out in the retail market where they belong and not brought into a white gallery and put up on a pedestal.”

Wong was briefly obsessed with thePrada flagship store in New York’s SoHo, which suffered severe smoke and water damage from a fire in January. Opened in 2001, the store was designed by renowned architect Rem Koolhaas and constructed at a cost of$40 million (US). The interior featured a giant wooden wave that looked something like a skateboard half-pipe, an expansive wall covered with dramatic designer wallpaper that was changed periodically, and spackling over nail holes that was purposely left unfinished. Wong already had a history with the place?—?just before the original opening, Prada had hired him to walk through and provide a second opinion on the finishing touches. But after the whole place went up in smoke, he developed a new proposal: leave everything as it is and seal the damage under a glossy clear coat. More than just wishful thinking, Wong floated the idea past the editor of Art Review magazine, who tried to sell the proposal to Koolhaas. Not surprisingly, the architect wasn’t co-operative. The store reopened in March, with new fixtures, floors, and wallpaper.

Wong may be getting more ambitious with the scale of his projects, but that doesn’t mean that he’ll be paying any less attention to the little things. There’s one photo in his portfolio that’s particularly telling?—?it shows a honeymooning couple snuggling together on the banks of a lake, posing for a touching portrait. It’s the kind of shot they might have hung on their living-room wall. But there, in the background, is Wong, flexing his biceps and looking tough. He has labelled the shot self portrait. Can such a prank really be considered art? “That ties into my work,” he says. “Stealing other people’s things.”•