“I have a philosophy now, borne out of much necessity, that sometimes things go wrong in order for them to go right. So when it was overcast on eclipse day in Cornwall in 1999, it enabled me to make the film that everyone agreed was much more me. Or when I trusted the light meter in a camera from another epoch, my near vanished film turned out more authentic to my project than anything I could have manufactured. But at the time, of course, these uninvited situations are unbearably painful and disappointing. To be persuaded by circumstance to take another route is never easy, and to trudge along that road to Damascus before the merest hint of conversion always takes some endurance, if not faith.

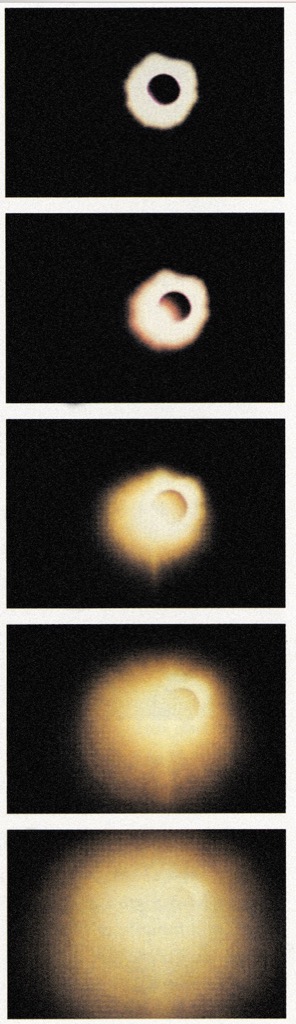

“And so it was in the summer of 2001, when I made copious plans with my friend Dick to travel to Western Madagascar to try once more to see a total eclipse of the sun. We survived the cancellation of our plane; we survived the guide and the journey, we survived everything and on the morning of June 21st, we even got the weather. But then during totality; during those two and a half most anticipated minutes, the camera fell down. Dick and I contributed jointly to cause this accident. I only write this because I think he might want to be retrospectively acknowledged for his role in the making of Diamond Ring. Suffice to say I was paralysed by the familiar disappointment. It took me nearly the whole of totality to react, and at that point I did something I rarely do, and would never have done: I zoomed in. And at the very moment I stop, with the sun in [the] middle of my viewfinder, the moon passes into the next phase, and the released sunlight overexposes my film and bleaches my frame.”—from Book One: Selected Writings (Steidl/ARC/Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 2003)