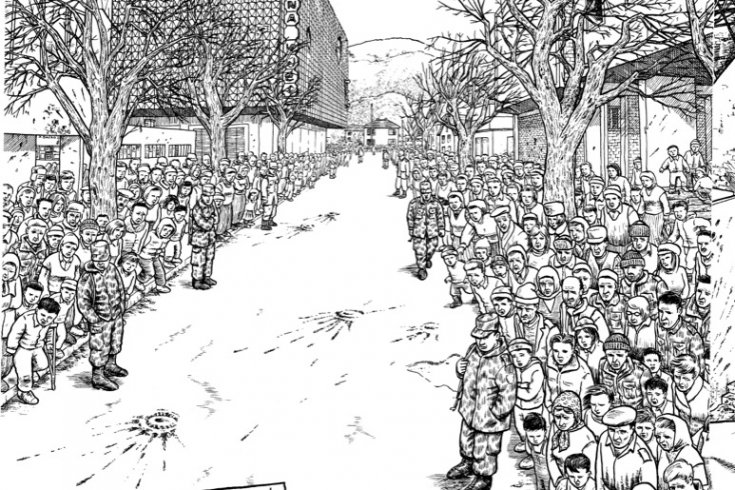

A stone bridge, a foreboding black sky, soldiers, knives, and quivering civilians—all in fiercely scrawled strokes. Slit throats and wild, leering eyes, somehow worse than the images that find their way onto television screens or magazine covers or Web pages. Pregnant women are dragged out of hospital beds and raped; men freeze to death while foraging at night through snowy mountains for food. Girls scheme for the latest pair of Levi’s. A soldier on leave stands in the rain belting out “We’re living it up at the Hotel California.” Welcome to Joe Sacco’s Bosnia.

Graphic novels, or graphics, mine a rich heritage, from Francisco Goya’s Disasters of War, his series of etchings recounting the atrocities perpetrated by Napoleon’s army during its occupation of Madrid, to the political cartoons of Otto Dix and George Grosz, each of whom documented World War I and the rise of the Nazis, to the underground comics movement of the 1960s and 1970s. A startling proportion of the current offerings are non-fiction, rendering history, journalism, and memoir into a frame-by-frame marriage of words and pictures. Art Spiegelman set the stage for all this activity in 1986 with his Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus, a depiction of his parents’ experiences during the Holocaust, in which he cast cats as the Nazis and mice as the Jews. The inheritors of Maus’s legacy include journalistic works by Sacco from his trips to Palestine and Bosnia, Marjane Satrapi’s two-volume memoir of growing up in revolutionary Iran, and Rosalind Penfold’s account of abuse.

Why use comics, an idiom perhaps best suited to humour and satire, to depict events as tragic as the Holocaust or the war in Bosnia or spousal abuse Non-fiction graphics may be symptomatic of a greater malaise—a creeping weariness with our hyper-digitized, over-photographed reality. Photojournalism has left us inured to the gory traumas it portrays. Graphics, on the other hand, are visceral and intimate, their scribbled outlines contrasting with the sharp edges and sharper colours of photography.

Spiegelman put the role graphics could play this way: “In a world where Photoshop has outed the photograph to be a liar, one can now allow artists to return to their original function—as reporters.” Graphic reportage offers the sense that it has been created in real time, that its slashes were drawn under the pressure of events. Photography once carried this banner, but perhaps drawing now has greater authority.

Joe Sacco’s Safe Area Goražde: The War in Eastern Bosnia 1992—95, an account of the author’s trip to the Balkans, threatens to explode off the page. In one almost schizophrenic sequence, Sacco recounts a single day in the war. “I thought it’s better to be killed while running than to stay in the same place. My daughter followed me, but my wife didn’t move,” says Izet, a man from Goražde. “I protected my daughter with my body, crawling down to the river. It took three hours,” Izet’s neighbour Emina continues, as a sea of people flee and we watch from all angles, frame by frame—the building rubble, the bloodied faces, the muddy fields, the icy river. The end result is not a tidy package but a scattershot portrait of the terror and death that engulfs an entire town. It is the collective voice of Goražde.

Sacco never tires of engaging the ironies and the absurdities of both his and his characters’ situations. It is his signature touch. Here he is, chasing a story in Palestine: “I need more details. Okay, this fellow knows someone who’s got better English, this way please,” and off we go, only to discover, “That’s it But this is second-hand info.” He’s openly self-mocking: “Okay, I’m sated, that’s enough of that, I’ve had my fun, I’ve got some burning tires and automatic fire to add to my collection…to my comics magnum opus.” And he is always deeply skeptical: “Palestinian victims all right! The real-life adaptation of all those affidavits I’ve been reading! The flesh and blood stuff! Up close and almost personal! But it’s time for me to go!…I’m off to fill my notebook! I will alert the world to your suffering!” The book is a raucous mixture of honesty, veracity, and wry humour.

Like Sacco, Marjane Satrapi goes beyond headlines and into the banal details of life—in this case, of the revolutionary Iran she grew up in. But where Sacco tells and shows all, filling each frame with a barrage of character and detail, Satrapi makes do with simple statements that leave much for the reader to pencil in. Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood is told by a precocious child protagonist. The tensions in her society seep even into her childhood games. In one scene, she imagines her six-year-old self as the Last Prophet and establishes the rules of a mini-regime: “Rule Number Eight: No old person should have to suffer.”

“In that case, I’ll be your first disciple,” her grandmother says to her. “But tell me how you’ll arrange for old people not to suffer”

“It will simply be forbidden,” Satrapi replies, with a sweep of her arms.

The modesty and straightforwardness of the book only emphasize the complexity of the girl’s family history—she is the great-granddaughter of a former emperor, though her parents are Marxists—and of the political situation in Iran. When she informs the reader that a theatre has burned to the ground, her articulation of the politics underlying the tragedy leads to a simple moral declaration: “The bbc said there were 400 victims. The Shah said that a group of religious fanatics perpetrated the massacre. But the people knew that it was the Shah’s fault!!!”

Even the most mundane family situations are informed by political events. The night of the theatre incident, Satrapi, clad in heart-patterned pyjamas, pads into her parents bedroom. Like any inquisitive child, she has been listening at the door.

“I want to come with you tomorrow,” she says.

“Where”

“To demonstrate in the street. I am sick and tired of doing it in the garden.”

“It is very dangerous. They shoot people.”

“For a revolution to succeed, the entire population must support it!”

“You can participate later on.”

“Sure, sure, when it’s all over.”

In the second volume of her memoir, Persepolis 2: The Story of a Return, Satrapi takes us to Vienna, where she has been sent to finish high school. There she learns that extremism is not confined to her native land, and struggles to adapt her liberal Iranian upbringing to the even-more-liberal Western values she encounters. In one image, she sits stiffly on the corner of the couch while her roommate and a boyfriend cuddle in their underwear next to her. She eventually returns home, where she discovers that behind closed doors, far from being the extremist dupes she has come to see them as, many Iranians are working out, shopping, and partying. The parties may end with a deadly police raid, but the scenes are otherwise stunningly familiar.

If we have come to distrust the pretenses of personal memoirs and reporters’ books, and our ability to respond emotionally to photographs has been dulled by what some have aptly called war pornography, then how do we continue to document, to record, to tell stories In the opening pages of Dragonslippers, narrator Rosalind Penfold teases readers with a Pandora’s box of horrors. She approaches the frame, clutching a box labelled “Burn these without looking” and asks “Do you want to see” She proceeds to reveal ten years of spousal abuse. Penfold’s drawings are simultaneously the kindest, most gentle, most powerful, and most brutal way of portraying this form of violence. As she tells us in her foreword, “My brain could rationalize and deny, but my art went straight to the truth.”

The by-turns furious and economical drawings of these artists, coupled with the urgently handwritten text that characterizes graphic non-fiction, restore unpolished, moment-to-moment immediacy to reportage and memoir. In their deft hands, one can almost feel the process of witnessing and remembering at work, with all its inherent anger and uncertainty, irony and humour. Life does not take place in sharp, colour-corrected focus, nor does it have clean edges and neat conclusions.