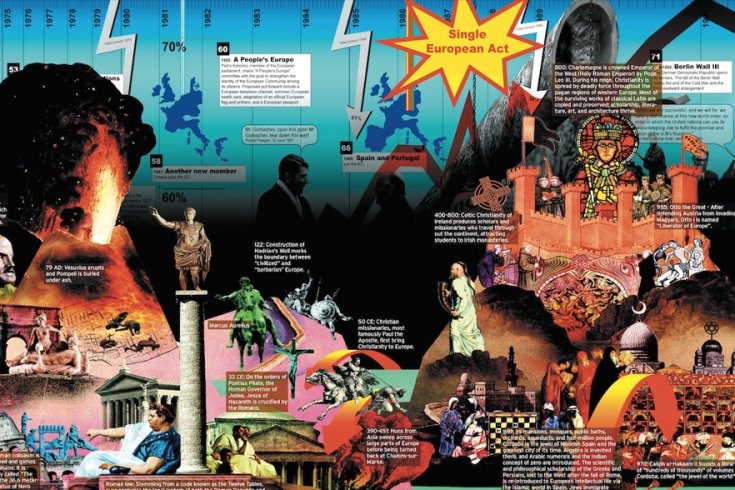

A shame, really, that no one thought to publish How The Muslims Saved Civilization back in the 1990s. Such a book might have outlined the debt owed by the great minds of the sixteenth- century Renaissance to Islamic scholarship, especially in astronomy, medicine, and math. Or the earlier bequeathment to medieval Europe of versions of Aristotle, Plato, and Euclid, courtesy of Muslim translators working in Moorish Spain. Or any of the other influences and encounters in what historian Steven Runciman has called “the long sequence of interaction and fusion between Orient and Occident.” How The Muslims Saved Civilization would surely have been welcomed by readers a decade ago, just as they welcomed Thomas Cahill’s 1995 account of heroic Irish monks who performed similar good deeds.

Unless, that is, something about linking Muslims with civilization in the title would cause confusion. Admirers of Cahill’s How The Irish Saved Civilization knew that by the term “civilization” the American scholar meant the recorded greatness of Greece and Rome, which was preserved by Irish scribes until Europe could climb out of its dark age and become civilized again. No offence was intended against the cultures of India or China or any other corner of the globe where, in effect, little of this history applied. This was the rise and fall and rise again of white Europe.

Would a book title in which Muslims, whose skin is generally less white and who are associated today with North Africa and the Middle and Far East, were proclaimed to have also played a role in the resurgence of Western civilization have been readily understood? Explaining that large numbers of followers of Islam once lived and flourished in places such as Spain and Sicily might have helped. The city of Granada featured Muslim public baths in most neighbourhoods? Residents of twelfth-century Salerno could have counted a hundred mosques inside their city walls? Who knew.

Regardless, September 11, 2001, put an end to warm-and-cuddly book ideas. Since the twin towers fell, the times have demanded blunt tomes with aggressive titles and subtitles that could, in different hands, double as recruitment slogans for one jihad or another. Historian Bernard Lewis’s What Went Wrong and The Crisis of Islam have swollen to bestsellerdom in part, one suspects, on the inflammatory nature of their monikers. If Lewis has any regrets about the names chosen, it may be because the real banner he wished to run across both dust jackets—the now-axiomatic “clash of civilizations,” which he coined in an earlier essay—was usurped by Samuel Huntington for his more nuanced The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order. Lewis has had to be content with subtitles that are locked and loaded: The Clash Between Islam and Modernity in the Middle East and Holy War and Unholy terror respectively.

Forget some waffling about forgotten cultural interactions or shared ancestries, and disregard the foreshadowings of history—say, the infamous razing of the library of Alexandria in ad 391 so that it could be converted to a church. The only acceptable narrative at present is the conflict between civilizations, one modern and righteous and the other in the throes of the terror and crisis that comes from being, so to speak, wrong. This may be a largely rhetorical clash, but when oppositional forces meet, whether in reality or in the media, the noise can be deafening. Among those publishing at maximum volume since 9/11 has been the historian and essayist Tariq Ali. Both his The Clash of Fundamentalisms: Crusades, Jihads and Modernity and Bush in Babylon: The Recolonization of Iraq give from the international Left at least as good as they get from the American Right.

But that same Tariq Ali has also nearly completed the sort of quiet writing project seemingly out of step with our loud age. A Sultan in Palermo is the fourth volume in the Islam Quintet, a series of historical novels that probe the lengthy encounter between Islam and Western Christendom. The series is revisionist in impulse, wishing to suggest that the dominant history of Europe in the last millennium, if not quite the lie told by the winner, as Napoleon Bonaparte once quipped, has certainly involved obscuring the truth about those who “lost” the continent. “If things go on like this,” a character says at the start of the first novel, Shadows of the Pomegranate Tree, “nothing will be left of us except a fragrant memory.”

The quintet begins in 1499 in al-Andalus. Queen Isabella is solidifying the reconquista of the land that Christians call Spain from the dark-skinned heathens who have been occupying parts of it for six centuries. Amid the slaughters, expulsions, and conversions-by-inquisition, one act of savagery stands out. Ximenes de Cisneros, the Catholic archbishop in charge of the dirty work, has sent soldiers into the libraries and private homes with book collections around the city of Granada, ordering that all Arab-language titles be collected for burning. Like many such gestures, Cisneros’ involves a backhanded compliment: these people care enough about books to be devastated by their loss.

Indeed, among the texts are several thousand copies of the Koran, many exquisitely crafted, along with “rare manuscripts vital to the entire architecture of intellectual life in al-Andalus.” The collection is both a testament to the sophistication of Moorish Spain and the envy of scholars in the rest of Europe. The priest is convinced that Muslims can be eliminated as a force in the Iberian Peninsula only if their culture is erased. He signals the torch-bearers to light the bonfire, then listens, unmoved, as helpless onlookers offer their faith’s timeless assertion of fidelity: “There is only one Allah and he is Allah and Mohammed is his Prophet.”

Moorish Spain, as embodied by the fictional aristocratic clan, the Banu Hudayl, whose mansion outside Granada was first constructed in ad 935, three years after the family left Damascus for the western outpost of Islam, is about to be eradicated. Literally nothing and no one will survive the fanaticism of the overlords, who are, by the by, primitive by comparison with those they exterminate. The last survivor of the Hudayls, an eleven-year-old child, has a knife plunged into his chest by a sociopathic teenage army captain. The epilogue, which jumps ahead twenty years, further darkens this compelling, if not always seamless, first effort at rendering history through narrative. The captain, revealed as Cortés, is shown entering the great city of Tenochtitlan, or presentday Mexico City, where king Moctezuma is naïvely waiting to greet him.

By beginning in Spain, Shadows of the Pomegranate Tree goes straight for the heart of Muslim grievances about their legacy in Europe. Ali may have chosen al-Andalus as his inaugural canvas because the story is reasonably well-known, especially the bonfire at Granada. His decision with the next volume, The Book of Saladin, to shift three centuries back to the region from which the Hudayl family originally fled, suggests a twofold ambition for the series. First impressions of the early novels are likely to focus on their portraits of Islamic societies in Mediterranean Europe. These sketches, vivid and warm without being idealized, have the freshness of images recently discovered beneath the paint of other representations. Much of the pleasure of reading Ali’s fiction lies in his detailing of daily life, both high and low, and daily appetites, including sexual and culinary—appetites and lives that have been too long hidden. As a novelist, he is possessed with a fine historical intelligence and a storytelling impulse that owes as much to Arabian Nights as it does to Tolstoy. Admirers of tales replete with scheming eunuchs and harem intrigues, women of complex lusts, and men who love women and men alike, won’t be disappointed.

But a more cerebral ambition underpins how history unfolds in the books. When lined up beside each other, the novels constitute a compare and contrast of the fates of those societies. As well as excavating the secret Islamicization of Europe, Ali is posing a question: why did Islam, once so pluralistic and intellectually progressive, ossify and withdraw to such a degree that it wound up isolated from the continent it helped civilize? In Moorish Spain, he identifies the force and animosity of external enemies as the principal cause. In other cases, the fault is largely internal.

The Book of Saladin finds the culture at perhaps the peak of its achievements. Salah al-Din, or Saladin, the legendary Kurdish Sultan of Syria and Egypt, arrives at the Cairo house of the Jewish scholar Ibn Yakub, who he hires as his personal scribe. Though Jerusalem was lost to the Christians in the First Crusade of 1099, Saladin’s rule over the cities of Cairo and Damascus has allowed for the evolution of an urban civilization far in advance of anything in continental Europe. His caliphate is also tolerant, welcoming Jews and Christians to dwell alongside Believers. All are People of the Book, sharing much of the Old and New Testament and many of the prophets. Saladin himself is revered for his generosity and fairness: a good ruler, as rare in the Islamic world as anywhere else.

The Sultan’s vow to retake Jerusalem, known to Arabs as al-Kuds, is within his military reach, so long as he can maintain unity among his emirs. History records Saladin recapturing the city in 1187, only to be confronted by still another wave of crusaders, including the English King Richard the Lionhearted. Ostensibly the victor in the Third Crusade as well, Saladin was worn down equally by battles with Christians and with his own fractious tribes. History also records that Islam did not achieve prominence again in the Holy Land until the rise of the Ottomans centuries later.

Making the boldest time leap in the series, The Stone Woman bypasses the glory days of the final Islamic empire to meditate on its long twilight. The novel, which details the story of a disaffected Turkish aristocrat named Nilofer who returns to her family home outside Istanbul in 1899, is a Chekhovian exercise in philosophical sighs and political inertia. Characters squander afternoons lamenting the retreat of the Ottoman Empire from the Europe that emerged out of the Renaissance. “Istanbul,” one character remarks, “could have been the capital of invention and modernity like Cordoba and Baghdad in the old days, but these wretched beards that established the laws of our state were frightened of losing their monopoly of power and knowledge.” The “beards” are the conservative clergy, who had, for instance, persuaded one sixteenth-century sultan that the printing press would be a threat to stability. Another character summarizes the sentiment among the family: “I think our decline is well deserved.”

The Stone Woman, with its purposeful inactivity and daring foray into the mind of a Muslim woman, is a striking counterpoint to the bustle of the other books, foreshadowing the condition of Islam still another century into its crisis. “Everything is being taken away and nothing is ready to take its place,” Nilofer warns her children. “It is this that turns many ordinary people into madmen and assassins.”

Such prophesy could well have compelled a fourth volume that actualized Nilofer’s darkest worries for 1999 or beyond. Instead, A Sultan in Palermo swings back to the twelfth century, this time in Sicily. First conquered by Arabs in 827, the island was retaken by the Normans in 1091. The majority Muslim population benefited, however, from a ruler, Roger II, who so admired Islam that he both adopted its customs and kept his less-admiring barons in check. As in Moorish Spain and the Damascus of Saladin, the Salerno of the “baptized Sultan” is a multicultural court in which Muslims, Jews, and Nazarenes live and work together. For Ali, these periods of fruitful coexistence are to be noted. History in the quintet isn’t a force above and beyond human agency. Civilizations don’t clash; only individuals do, and they can always resolve otherwise.

A Sultan in Palermo is the first volume to appear since 9/11. For the most part, the book is unaffected by the rising screech of debate in journalism and non-fiction. The tale of the efforts of al-Idrisi, a court scholar and adviser to Roger II, to stave off the disaster of his ruler’s impending death keeps pace in both plot and detail with The Book of Saladin, the finest of the novels so far. That a scholar should fail to stop the Normans from slaughtering Muslims after a change in leadership, thus initiating the erasure of Islam in Sicily, is no surprise: the leisurely wind-down of the Ottoman Empire is a luxury afforded to few Arabs in Europe. Extinction was more the norm.

Only Ali’s portrait of the historic figure of al-Idrisi betrays what may be a post-9/11 frustration with the ways that novels go about revealing truth. When not struggling to save his people or having sex five times in one night with his wife’s sister (called the “Five Obligations”), the fifty-eight year old is pondering scientific and political advances not due to occur for hundreds of years. These include the theories of gravity and natural selection, and the Marxist plan for the fair distribution of land among peasants. He even offers tips on healthy eating.

Idrisi is, in short, a Super Arab, and had T-shirts been the fashion in medieval Sicily, he might have had one printed with “Muslims do it better.” This mild lapse into the megaphone rhetoric of our age, while forgivable given the author’s engagement with politics in addition to literature, should still be cautioned. Even partisan fiction can’t survive too much cheerleading. More important, it is precisely the reserved, measured truths about humanity contained within the Islam Quintet that we “People of the Book” need to be reading right now.

There is a riddle yet to be answered by the series. Tariq Ali has now balanced stories that explore European Islamic societies destroyed by external forces with those brought down by their own internal failings. As such, the fifth novel could be expected to either tip the balance or propose a new dynamic. My guess is that Ali may finally plunge into the early twentieth century, possibly the Palestine of fading empires and competing ambitions and needs. Here, too, he would find a Muslim society at risk of obliteration, and rulers mostly weak but occasionally strong, and instances of clash and cooperation alike, and more than a few passionate individuals who, though determined not to become fragrant memories, may still end up forgotten, history being what it is.