Just after sunrise on Ottawa’s Rideau River. Even without caffeine my cerebral cortex buzzes with the mishmash of sound: moving water, bugs, a dog, the drone of traffic. Our national capital is a sober, eighty-hour-a-week city. A place where not only does a person have to trudge to work through malarial heat and bone-snapping cold, but must do so while enduring the indignity of a chest covered in plastic conference and ID badges—a look known as “The Full Ottawa.” Was that why being on this stretch of river, just a long roll cast away from Parliament Hill, gave me such a dirty little thrill? To be going mano-a-mano with a trout the size of my index finger just as the first low-level functionaries were booting up their laptops in nearby Centre Block. To be standing kidney deep in tea-coloured water while the tech-heads, dreaming of dot-com glory, hurtled by toward their veal-fattening pens in the outreaches of Kanata.

Ah, gone fishing. Are there any other two words that can so easily conjure up the joys of performing a pointless activity when the whole world wants you to do something worthwhile? Let’s be honest here: I’m hardly the first person to note that fly-fishing has its share of transcendent moments. Sitting in a boat on the Miramichi River watching an eagle hit the water and rise with a salmon in its talons. Standing in a blaze of autumn leaves on Cape Breton’s Margaree River with only the swish-swish-swish of our rods breaking the early-morning silence. Feeling the caveman-like kick of hooking a fish and then hauling it, gasping, onto dry land—well, it just doesn’t get any better than that.

So what does it really say about me that sometimes all that Norman Maclean (A River Runs Through It) stuff pales? That there are times, many times actually, when I’m just as happy to be fishing on an ugly bit of city water a few blocks from the nearest Starbucks. When that happens—and I’m loath to admit this—I get an inexplicably perverse pleasure to be on an urban shore, waiting for something, anything, to take my fly while the office folk rattle past. They have no idea that I am futilely beating the water below. How much is there really to envy about a man who knows in his heart that the only way he’s going to land a fish is if one happens to swim by, open-mouthed at the precise moment that his fly lands? Except for one small thing: I’m the one standing in the river. They’re off to the Nortel campus, wondering if any decent severance packages will be around when the next axe falls.

It’s so easy to try to attach some virtue to it—to go on at length about the quest for angling mastery and fishing-as-a-metaphor-for-life. Maybe that’s reasonable if you’re casting for salmon in Labrador or stripers on the Bay of Fundy. It probably even has a certain resonance if you happen to be fishing in Calgary, where it’s possible to land mammoth rainbow trout on the Bow River. My question is whether all of that bull really applies when you’re fishing somewhere where ac/dc screams from a passing muscle car and the prettiest thing in your line of vision looks to be a couple of condoms floating past in a gasoline slick.

Now, I fully understand that singing the praises of urban angling is unlikely to earn a guy a place in the next collection of classic angling essays, but, I didn’t grow up in an outdoorsy family. The first time I had a rod in my hand was in my late thirties, when tying a hook on my microfilament line was already problematic for my fading vision.

All that means is that I’m unencumbered by any sort of fish-catching expectations. The best fisherman I know keeps a running count on the number of salmon he’s caught. It now extends, I imagine, into the thousands. I, on the other hand, have landed precisely three salmon, a few dozen trout, and a bunch of other fish I can’t even identify. So none of my stories ever revolve around large numbers of fish landed, let alone the other staple in the angler’s repertoire, the big-fish yarn. What’s more, since I know nothing about practical matters—like where fish tend to lie in water—I’m pretty much free to wet a line anywhere, anytime.

A guy needs a vague purpose to be out there. At least I do. But fishing, even the urban kind, is one of the few occasions when a person can justify standing still and doing nothing. When you don’t really have a chance in hell of reeling something in, your mind tends to wander. The world—even when you’re looking at it from behind a service station, or at the end of a skanky dock—seems full of infinite possibility. You’re back in that Saturday-morning, summer-vacation aimlessness of your childhood. (Who is tougher, Gordie Howe or Captain Kirk? How come cherry Lik-m-aid tastes like fish sticks? Betty or Veronica?)

Which is nice, since I really couldn’t care less about eradicating fish. It’s not just me. Recently, I called Bill Milliken, former press secretary to John Manley and now a public-relations consultant, a guy whom I used to run into on the same stretches of water near Parliament Hill. It was the toys that hooked him first—the beauty of the man-made flies, the timeless efficiency of reel and rod. “Then I started fishing along Champlain Bridge, and over in Britannia Bay on the Ottawa River,” he recalled. “It was rush hour and I couldn’t hear a thing. It was like I was in this whole other world right underneath the overpass.”

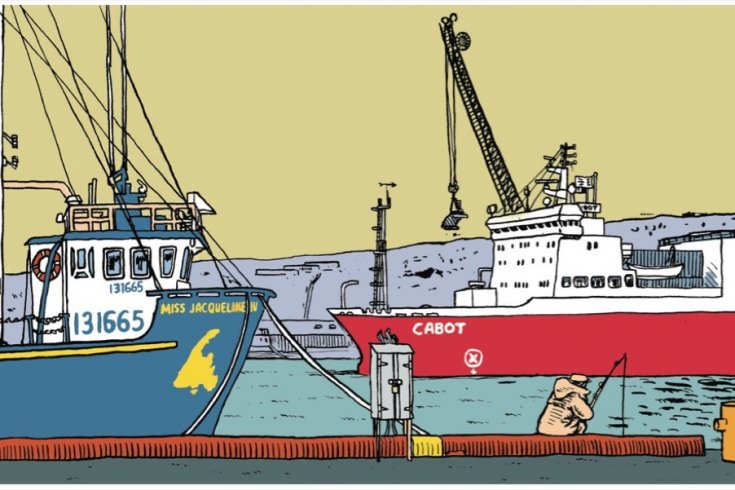

With no sublime view to distract, your sense of wonder boots up again. In this state of mind, from this new angle, the crap that you’d normally ignore suddenly seems interesting. All I know is that from a few feet away, the piers holding up a bridge look like a marvel of engineering beauty, and the derelict tugboat you’re casting alongside has an earthy charm. Water, no matter how pestilent, is worthy of attention when you know a school of silver-backed mackerel has just arrived from the open ocean, like a carload of really cool city kids showing up at a country dance.

In Ottawa, I used to park my car near an overpass, climb over the guardrail, and carry my waders and lunch down into the ravine. It was a weird spot: equal parts marshland and riverbank, but with enough graffiti decorating the overpass underpinnings to give the feeling of an abandoned ruin. Down there, my spidey senses invariably tingled with the same subversive delight I got as a kid clambering through an abandoned building. It was the joy of knowing you were somewhere you shouldn’t be, an intoxicating thing for a middle-aged man with no intention of ever going to Las Vegas. This was a secret place where college kids partied and Jane Hathaway types in Tilley hats probably showed up in fevered pursuit of a cedar waxwing. One day, sloshing around down there, I saw a young woman sitting on a rock reading a book. Another time I watched a fierce-looking guy, who might have been sleeping nearby, move through the brush like a ghost. But I never once saw anyone else fishing.

That thrilled me to no end. Even if sometimes a little company is nice on the water. It’s a truly wonderful thing to watch your daughter shriek with delight as the old Chinese guy casting for dinner along the Rideau Canal pulls in a sunfish. Just like it’s great to be watching through your son’s eyes as the line he has thrown out barely misses a pair of scuba divers looking for something below the surface in Halifax Harbour.

If you’re after larger-than-life men engaged in heroic deeds, it must now be apparent, the city shoreline is not the place to find them. Even so, there’s a banality to urban fishing that’s comforting. Ricky Anderson of Halifax, a former Canadian welterweight boxing champ and another late convert to city fishing, knows precisely what I’m talking about. “My brother-in-law introduced me to it in 1995,” he explains. “My mother had passed away and I was grieving. The first time I threw that line out I felt at peace.”

Now Anderson and his sons live for the annual run of mackerel through Halifax Harbour. When they’re on the move, if your timing is right, you can get three or four mackerel on the line in a few seconds. I’ve never actually experienced that rush: whenever my kids and I arrived, the miraculous event had just ended and there were always a couple of guys walking away with buckets full of fish. (Mackerel, because of the quick tour they make of Halifax Harbour, are perhaps the only edible fish caught in those murderously polluted waters). We’d hustle down anyway to fling heavy lead-headed jigs with spinning rods as far into the current as possible. An old boot or a child’s doll would float past. Occasionally, we might even see a seal. In the fall it gets cold fast on the Halifax arm. Yet, we were always pleased to just stand there, steam coming off our breath, doing something just this side of pointless.