After much deliberation that morning in July 2000, Ben Hoffman decided on dress pants and a pressed shirt with no tie. He would carry no recording devices, fearing that the Ugandan rebel leader Joseph Kony might mistake him for a spy. Hoffman, one of the world’s top international conflict mediators, needed to be careful. Nothing suggesting he was a cowboy, nothing suggesting ulterior motives. Although not widely known in the West, Kony, the leader of the terrorist Lord’s Resistance Army (lra), was then, and remains now, one of the world’s most dangerous men, and quite possibly its cruellest. Hoffman had just heard that Kony had executed the last two men who tried to negotiate with him.

His nerves jittery, Hoffman, then forty-nine, left for the Khartoum airport with his associate, former US diplomat Doug Archer. A few hours later, they landed in Juba, in southern Sudan, where they were greeted by two officers working for the Sudanese deputy director of external security, Yahia Babikar, who oversaw secret operations in Sudan. When Hoffman had asked to meet the elusive Kony, Babikar, a man Hoffman invariably found charming, had made it happen.

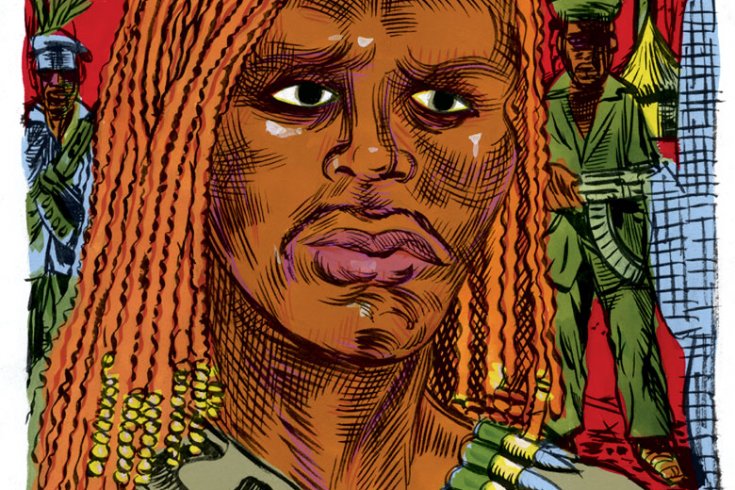

Before leaving for Nsitu Camp, Kony’s secret military base, the group stopped at a corner store to buy a crate of Pepsi. They set off through the forest, finally reaching a checkpoint where an lra soldier waved them through. Surprisingly, the soldier was an adult. Kony’s army at the time included some 6,000 children abducted from northern Uganda, making up an estimated 90 percent of his corps. Some were as young as seven; some were girls who served double duty as sex slaves. Hoffman hoped to negotiate the children’s release, paving the way for a peaceful end to the civil war the lra had been waging in Uganda for the past fourteen years. From there, perhaps, he could achieve the primary aim set out for him by his boss, ex-US President Jimmy Carter: an end to one of the world’s longest-running conflicts, the Sudanese civil war. Getting the lra to stop interfering in southern Sudan would be a good start.

Forty-five minutes later, Hoffman’s entourage pulled up to Nsitu Camp. Many who have escaped from Kony have reported that the dead and dying bodies of children hang around the perimeter as a warning to those who think of leaving, though Hoffman saw no evidence of this. He went inside the thatched compound and found Kony, a tall, lean man in his mid-forties with glasses and short hair, surrounded by his senior commanders. They greeted each other warily as the Sudanese cracked open the crate of Pepsi and passed the bottles around as an icebreaker.

Kony quickly launched into a diatribe, spewing insults and grievances at the group as he theatrically waved a small red book Hoffman thought might have been the Bible. Hoffman’s years of experience as a negotiator had built to this moment. He would not be defensive. He would try to relate to Kony and, above all, show no fear.

“The fear, you’re aware of it,” Hoffman would later reflect. “You’d be a fool if you weren’t.” Standing near him was Kony’s right-hand man, Vincent Otti, who had overseen mass slaughters and routinely commanded his troops to hack off the lips, noses, and ears of Ugandan military sympathizers. “This was not a politician,” Hoffman recounts. “This was a soldier, a warrior.”

Kony was the politician in the room. He demanded that Hoffman tell him why unicef was stealing his children and argued that his army wasn’t made up of criminals living in the bush, that they had a political objective. He was upset that he had been excluded from talks held seven months earlier that had produced an accord between Uganda and Sudan.

Hoffman was surprised. He’d expected a juvenile, spirit-possessed psychopath. But here was a man who seemed to make sense. He told Kony he was there to request that the rebel leader hold talks with representatives of the Uganda government, headed by Yoweri Museveni. He explained that he’d been hired as an impartial mediator to help Uganda and Sudan become better neighbours and that he’d been authorized by Museveni’s government to request talks. Kony stretched his forefinger and thumb into the shape of a gun and pointed at Hoffman’s head. Hoffman imagined the sensation of a bullet going through the back of his skull. Then Kony placed his gun hand on the table. “You are not my enemy. My enemy is Museveni,” he said. “We agree to talks.”

That night, Hoffman and the Sudanese officers ate goat stew on the out skirts of Juba, their spirits high with the thought that peace was on its way. That was the best meeting with Kony in a long time, the Sudanese said. But their hopes would soon be dashed. Kony would not meet with Hoffman again, thousands more children would be abducted, and Sudan’s internal strife would continue along its path to Darfur, and genocide. What made this civil war so unstoppable?

Hoffman’s long journey to Sudan began decades before, in 1971, when, as a long-haired twenty-three-year-old, he quit his job driving a dump truck in Kitchener, Ontario, to become a correctional officer. When his brother-in-law, a prison guard, first suggested the idea, Hoffman responded with distaste. “You mean being a guard?” he asked. “We don’t call ourselves guards anymore,” his brother-in-law replied. “We’re correctional officers. Your psychology degree will serve you well.”

His hair cut short, Hoffman entered the cell blocks of a Guelph, Ontario, correctional centre shortly after. He quickly advanced to upper management with the Ontario Corrections Ministry, where he stayed for nine years, earning a master’s degree in psychology in his spare time. After quitting his job in corrections, he found work managing large-scale projects to help battered women and their abusers and, later, writing diagnostic assessments of convicted criminals for use during sentencing. Hoffman was becoming an expert on the dark recesses of the criminal mind, and where others saw an abyss he saw cause for hope.

By the early 1980s, he was at the centre of a movement in the Canadian criminal justice system to switch from “retributive” to “restorative” justice, which has a stronger focus on healing, reconciliation, and victims’ rights. He became obsessed with the concept and, believing strongly in its ability to make the world a better place, returned to school to study international conflict resolution, first at Tufts University in Boston, then at Harvard, and finally at the University of York, England, where he received a Ph.D. Along the way, he found time to run unsuccessfully as a candidate for the Progressive Conservatives in the 1988 federal election.

In 1992, Hoffman co-founded the Canadian International Institute of Applied Negotiation (ciian) in Ottawa, which trained Canadian peacekeepers working abroad. He launched his own mediation company and negotiated a number of high-profile cases, among them environmental disputes and sexual-abuse charges against the Catholic Church.

The most famous of these was a landmark case involving 142 men (a number that eventually grew to almost 1,300) who were abused at two Ontario Catholic schools—St. Joseph’s in Alfred and St. John’s in Uxbridge—from the 1940s to the 1970s. The men sought redress from the Toronto Christian Brothers, who ran the schools, but rather than going through the court system they asked Hoffman to design an alternative dispute-resolution mechanism that would allow them to reconcile with the church in a way that the courts would not. Hoffman arranged for apologies from the government and the church, a mass for the victims, and financial compensation that included a college fund for the men’s children. In the process, he created a model for alternative dispute resolution in Canada. Retired Senator Douglas Roche, who worked on the case, says Hoffman’s approach to reconciliation was “visionary.”

Hoffman’s call to the world stage came in 1994, after he spoke at a unesco seminar about the emergence of inter-ethnic disputes in the Balkans and elsewhere following the collapse of Communism in eastern Europe. He says most of the people present agreed with the explanation, advanced by Michael Ignatieff and others, that these conflicts were related to feelings of deep-rooted ethnic identity. Hoffman took a different view. “I felt it was a struggle for power and resources disguised as ethnic conflict or ethnic rivalry,” he says. He impressed the delegates, and soon found himself travelling to places such as Ukraine and Romania—assessing, mediating, and trying to prevent violence from breaking out.

In late 1999, a headhunter working for Jimmy Carter called. The former president had a well-known track record as a peacemaker: he’d helped bring the Korean peninsula back from the brink of war, prevented a US-led invasion of Haiti, mediated in Liberia, Ethiopia, and Eritrea, and created an opening for the peace process in Bosnia (accomplishments that would earn him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002). Still, he’d had his share of disappointments and he feared that his initiatives were flagging in the era of inter-ethnic conflicts. He wanted someone capable of wrestling belligerents to the negotiating table, and none of the scholars and ambassadors who had applied—people from the world of Track One diplomacy, with its cocktail parties for elites—seemed quite right. Carter wanted the entrepreneurial Hoffman to be his director of conflict resolution at the Carter Center. Hoffman accepted the position and moved to Atlanta.

Sudan became Hoffman’s priority for an unusual reason. The Center funds a group of health experts dedicated to the worldwide eradication of guinea-worm disease—a debilitating illness, contracted from contaminated drinking water, that sees a worm measuring up to three feet long incubate in the human body before extracting itself via a painful skin ulcer. Within two weeks, the health experts brought Hoffman into their offices. They told him they had been purifying infected water sources since 1986 and had succeeded in reducing worldwide incidence by 98 percent. The last remaining frontier for the disease was Sudan. “The civil war must stop for three to five years,” they told him. “We cannot get into little villages because of the war.”

Carter also wanted Hoffman in Sudan. It was not just the guinea worm—the war was destabilizing the entire region, and Hoffman’s views on the causes of inter-ethnic conflict appeared well-suited to sorting it out. Although the conflict appeared on the surface to be a religious battle between Arab Muslims and black Christians and animists, the presence of oil in southern Sudan suggested other factors at work. The national oil companies of China and Malaysia, as well as Calgary-based Talisman Energy, were all drilling in the South, pouring revenue into government coffers and exacerbating the grievances of southern rebel groups.

The US government, too, was making things worse by overtly supporting rebel groups in the South. The Clinton administration had dubbed Sudan a terrorist state, imposing sanctions in 1996 and then, in August 1998, firing seventeen missiles into a Khartoum suburb to destroy an alleged chemical-weapons factory. Carter blasted the administration in an article in the Boston Globe in December 1999, charging that they were “committed to overthrowing the government in Khartoum.” And so, before leaving for Africa in 2000, Hoffman went to Washington to meet with Clinton’s Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright. He put in a plea for the administration to rethink its approach, then, a week later, left for Sudan.

There is a sacred liturgy in mediation, as it is taught in universities, that mediators do not negotiate or offer solutions. They are impartial facilitators. As he boarded the plane for Africa, Hoffman was planning to violate that basic tenet. He was determined to wage peace in Sudan, dragging the warring parties to the table personally if he had to.

Sudan is Africa’s largest country, spanning 2.5 million square kilometres. It encompasses the dunes of the Sahara and the banks of the Nile, and has an estimated population of 35 million, two-thirds of whom live in the predominantly Muslim North. The less populous central and southern regions of the country possess generous oil reserves, and, in theory at least, Sudan should be quite wealthy. Instead, it has been devastated by civil war for all but ten years since gaining independence from joint British-Egyptian rule in 1956. Since 1983, the war has killed more than 2 million people in the impoverished South, and displaced another 4 million.

Hoffman landed in Khartoum without any specific authority from either the Sudanese government or the southern rebels to broker a peace deal, but he did have a place to start. Six months earlier, in December 1999, Jimmy Carter had helped the enemy states of Sudan and Uganda reach a peace agreement, signed in Nairobi, that was widely seen as an important step to ending the Sudanese conflict. The most important provision of the agreement called on both countries to stop supporting each other’s rebel armies. Uganda had been supporting the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (spla), the southern rebel group that was waging the insurgency against the North, and Sudan had been backing and hosting Joseph Kony’s lra, which was fighting in northern Uganda.

Shortly after the deal was signed, however, the lra had aggressively attacked northern Uganda. The Nairobi Agreement was in danger of falling apart, and Hoffman knew why: the two rebel armies weren’t at the talks. “You always strive to get all the stakeholders to the table,” he later told me. “You don’t want someone who was left out to try to torpedo it. You better bring in the rats and the nasties to see if you can co-opt them.” Six months after the Nairobi Agreement had been signed, he would have to start all over again.

He flew to Kampala, Uganda, to make sure that President Museveni was still on board. Sitting under a shade tree on the expansive lawns around his palace, Museveni told Hoffman that the Sudanese government had designs on Islamizing Africa. He said he would never cease offering moral support, at least, to his persecuted African brothers in southern Sudan. But he reiterated the terms of the Nairobi Agreement: if Sudan stopped supporting the lra, he’d stop backing the spla.

The next day, Hoffman flew to Khartoum to meet with the Sudanese president, Omar Hassan al-Bashir, who said that his government wanted a strong and united Sudan, not one carved up into pieces. Hoffman felt that al-Bashir wanted peace but he understood that Sudan’s internal politics were complicated, and believed that al-Bashir was accommodating hard-line Islamists in his government who would not accede political control of the South lightly. With al-Bashir handcuffed and the South seeking nothing short of self-determination, the situation was stalemated.

Hoffman decided to step back from the Sudan conflict. He flew to Juba for his seemingly successful meeting with Kony at Nsitu Camp, then spent months trying to get the lra to negotiate with the Ugandan government. He took extraordinary measures to keep Kony involved in the process. At one point, after the lra leader had stopped responding to his entreaties, Hoffman dispatched secret messengers to his bush camp with a satellite phone rigged to dial only Hoffman’s number. lra commanders got hold of the phone and called him repeatedly, begging for peace talks. When it became clear that Kony himself would not respond, Hoffman went back to work on Sudan.

He spent nearly two years trying to get the spla and al-Bashir’s government to talk, but each time a breakthrough seemed at hand, something went wrong. The main parties simply would not get together. The United Nations was no help, as it had become preoccupied first with Afghanistan and then with Iraq, and Hoffman encountered nothing but resistance when he tried to get the economic and military leverage of the US government behind the peace process. In early 2002, he concluded that one of the biggest roadblocks to peace was the United States—specifically, the long and influential arm of the Christian Right.

When George W. Bush became president in 2001, most observers expected him to continue Bill Clinton’s policy of belligerence toward Sudan. But Bush surprised many by ordering a Sudan policy review in his first month in office. A vocal lobby effort quickly began, with different parties vying to influence the review before it concluded in July of that year. Certain groups, particularly those associated with the Christian Right, opposed the negotiations. In some cases, Hoffman says, hawkish lobbyists were asking the Bush White House to “bomb the piss out of Khartoum.” But Bush appeared to favour engagement, and on September 6 he appointed former Senator John Danforth as special envoy for peace in Sudan.

Five days later, the World Trade Center towers came crashing down, and the idea that Sudan, the incubating ground for Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda, was a pariah nation that needed to be confronted took on new resonance. Hoffman and Carter redoubled their efforts to get Washington committed to the peace process. In spring 2002, Carter set up a meeting in North Carolina between Hoffman and the Reverend Franklin Graham, head of the international charity Samaritan’s Purse, and son of Reverend Billy Graham. The younger Graham was arguably the most powerful voice of the American Christian Right and was known to have President Bush’s ear. Hoffman hoped to convince him that Bush should work for peace with Sudan’s existing government. It would be a tough sell. Graham had strong personal feelings about the Sudanese conflict because government forces had bombed near a Samaritan’s Purse hospital in the South. He had also argued before the US Senate in 2000 that the world had a moral obligation to overthrow al-Bashir’s regime. “We see burned-out villages, mutilated bodies, families torn apart, and religious persecution equal to that of the Holocaust,” he said. “The government of Sudan has purposely targeted the Christians and minorities of other faiths.”

To Hoffman, Graham’s analysis was simplistic. In truth, both the government and the southern rebels were guilty of gross human-rights abuses. It was a dirty, hateful war, focused primarily on power and oil, with abuses on both sides (and in fact, the vast majority of southern victims were animists, not Christians).

Hoffman’s meeting with Graham proved to be one of the most difficult in his thirty-year career as a mediator. The first words out of Graham’s mouth were to ask about Hoffman’s religious beliefs. He sidestepped and got down to business, arguing that if Khartoum was engaged in peace talks, the US would be able to hold the Sudanese government accountable for human rights abuses against Christians in the South. His appeal didn’t work at first, but he persisted, grinding Graham down by recounting his past experiences with restorative justice in prisons. Two-and-a-half hours later, Hoffman says, Graham turned to him and said, “Okay, let’s give peace a chance,” adding, “but we’re not going to give them too long.”

Hoffman believes Graham took this message forward, and that this contributed to the Bush administration’s increasingly firm commitment to the peace process. In October 2002, the president signed the Sudan Peace Act into law. The Act pressed the North and South into good-faith negotiations by combining promises of aid with threats of reprisal. The Sudanese government, which had seen the US topple the Taliban in Afghanistan earlier that year, proved receptive.

The Carter Center’s efforts with Museveni and al-Bashir were paying off, too. Sudan and Uganda were no longer supporting each other’s rebel armies, paving the way for talks between northern and southern Sudan. Before these talks began, Hoffman spent four months teaching the Sudanese rebels and the government to talk to each other without being antagonistic. He and his team gave mediation and negotiation workshops to most of the senior commanders of the spla, and trained community and religious groups, and delegates from the Sudanese and Ugandan government. When the talks finally began in Nairobi in 2003, the two sides quickly declared a ceasefire, which led in turn to a January 2005 peace treaty ending the war. The deal made the leader of the spla, John Garang, vice-president of Sudan and gave the South formal religious independence from the North, with an option to declare full political independence after six years. Oil revenue-sharing was set at fifty-fifty.

But even though his work would help achieve this breakthrough, in 2003 Hoffman was still deeply troubled, particularly by Joseph Kony, who was still terrorizing northern Uganda with his army of abducted children. He wanted to continue his work there, but ultimately concluded that Museveni had a political interest in seeing the war with the lra continue. Though he felt torn apart by the decision, he recommended that the Carter Center step away. Since then, the conflict in Uganda has degenerated into what the UN calls the world’s most neglected humanitarian crisis.

The Center was also preparing at the time to withdraw from Sudan (with the exception of its guinea-worm program, which it expects to complete in 2009), but Hoffman went to Carter and argued against leaving. He believed the Center needed to establish grassroots networks among religious and rebel groups to ensure that the agreement was implemented. He was also concerned that some important, interested parties, including the people of Darfur, had not been heard, and he believed the Center could wire those voices into the talks. Carter turned him down, leaving the process to power players like the US government. Hoffman, deeply frustrated and worried that violence was percolating, realized his time at the Carter Center was over.

He returned to his home near Eganville, Ontario, and spent some time with his wife and sons, shedding the trauma he’d accumulated in the bush. After a short break, he accepted a fellowship at Tufts University. He had just completed a comprehensive “how-to” report on reducing political violence when Darfur ignited.

The Darfur region in western Sudan, population 6 million, has a long history of skirmishes between nomadic Arab-Muslim herdsmen and black-Muslim landowning farmers over limited water and grazing lands. In 2003, these conflicts were intensifying, and war seemed imminent. Of particular concern were two new rebel groups, the Sudan Liberation Army and the Justice and Equality Movement. Both felt marginalized by the government, and by the peace process then under way between the North and South. Not including them in talks, Hoffman says, was the crucial missed opportunity. When the peace process had begun in 2002, the Darfur groups, feeling abandoned, had asked to participate. “It’s my understanding that they requested to be a party to those talks,” Hoffman says, citing a confidential but authoritative source. “They were rejected.” His Carter Center team had trained many of the negotiators and mediators working in Nairobi, but had been powerless to implement his primary rule: always ensure that all stakeholders are at the table.

In early 2003, the Sudan Liberation Army and the Justice and Equality Movement began exerting their revolutionary muscle by attacking government posts. In response, Khartoum labelled them bandits and contracted groups of increasingly well-organized, predominantly Arab-Muslim militiamen, known as Janjaweed, to quash the rebellion. The result was what many are calling a genocide.

In the fall of 2004, Hoffman wrote to Yahia Babikar, the man who had arranged his meeting with Joseph Kony. He believed Babikar was now liaising with the Janjaweed. “I asked him, ‘What is going on, my friend? I mean, surely to God . . . ’ and he wrote back: ‘I remain optimistic that we’ll get through all this stuff.’ ” The Sudanese government was distancing itself from responsibility for the violence, even as it used the Janjaweed to kill the rebels. It was a replay of the support it had offered the lra in its fight against the spla.

When world attention finally turned to Darfur in 2004, almost a year after the violence began, diplomats again found themselves working backward from a crisis situation. Hoffman insists, though, that diplomatic ignorance actually prevented the conflict from being addressed sooner. “People get to do this type of thing who don’t know what they’re doing,” he says. “But they get to do it because they have the ranking. They are the diplomats, the heads of state. They’ve arrived.” World leaders think they have nothing to learn from trained negotiators, he continued, but often “they get it wrong, and badly wrong.”

New senator and retired general Roméo Dallaire agrees. “Conflict resolution is not for amateurs,” he says. When he looks at the toothless resolutions coming from the UN on Darfur, he is reminded of the ones issued before the Rwandan genocide in 1994. “We’ve now got two genocides in recent times, and the response has been the same.”

UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan attempted to address UN ineffectiveness this spring by pushing the idea that the UN has the “responsibility to intervene” in situations of mass murder, repression, and/or ethnic cleansing, because the need to address such atrocities trumps concerns about violating national sovereignty. But reform will be slow in coming, if it comes at all, and politics and national self-interest will be difficult to overcome. Even Canada, a strong advocate of UN reform and the intervention concept, refused to prevent Talisman from drilling in Sudan. (The Canadian company, under pressure from shareholders, sold its stake there in 2003.)

Nor has Canada been much help in Darfur. Last September, Paul Martin chastised the UN General Assembly for its failure to stop the killing, but his government has accomplished little of practical value since—with the exception, perhaps, of a $90-million aid increase to southern Sudan, announced in April, which it folded under the rubric of a “multifaceted approach” to the country’s conflicts. Dallaire says Canada is unlikely to have a genuine impact. “Canada doesn’t have the capability to meet its words about Darfur. It doesn’t have the troop capability, nor the assets to deploy,” he says. The US, which does have the assets, has been slow to respond in the absence of clear political imperatives like fighting terrorism, access to oil, or catering to the Christian Right. The European and African Unions have also accomplished little.

Between 200,000 and 400,000 people have died since 2003 in Darfur, and more than 2 million others have been displaced. Hoffman worries, moreover, that the instability there will jeopardize the fragile truce in the South, even as a multinational peacekeeping force (including a small complement of up to thirty-one Canadian soldiers) prepares to deploy there.

Sitting by the fire at his Eganville home in the winter of 2004, Hoffman, grey-haired, goateed, and broad-shouldered, sips a cup of green tea and reflects on his attempts to wage peace in Sudan. He talks about what people like him bring to the peace process. Mediators know the rules, he says, and can help prevent bloodshed, but he believes they have stayed hidden behind masks of neutrality for too long. Been too soft. This has marginalized them, and kept them out of the most important diplomatic arenas.

A few months after this fireside chat, I emailed Hoffman to ask about Darfur’s prospects; the region’s rebel groups had walked away from peace talks earlier in the spring. He responded from Guinea-Bissau, one of the poorest countries in Africa, where he was working to prevent an outbreak of violence. The reply was jumbled: spelling mistakes, no capitals, and strange characters from his Portuguese keyboard. He wrote of the complications involved in negotiating such conflicts: the varying needs of international diplomacy, aid, human rights, and international justice. He decried the lack of a strategic framework for co-operation among these often competing interests. But he remained optimistic, writing at the last, “It is possible to craft peace processes that will reflect what the people in a given culture want and need, so that justice is done.” If there was hope for ending decades-long civil war in southern Sudan, there may yet be hope for peace, and reconciliation, in Darfur.