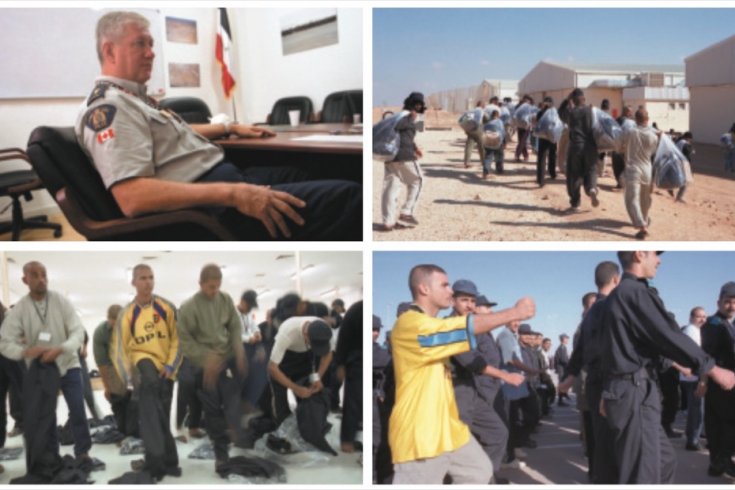

With his oval glasses, lean frame and balding head, rcmp staff sergeant Paul Marsh doesn’t look like the type of man who would leave his wife and two daughters to teach Iraqi police cadets how to shoot people. Last year, the relentlessly polite Marsh, who says “heck” instead of “hell” and collects vintage Coke bottles, was manning a desk at the rcmp’s media-relations office in his native Ottawa. Now he is a small but important player in helping to secure Iraq and help with Canada’s diplomatic push to ease tense relations with Washington. His mission begins at sun-up when he drives to the eastern outskirts of Amman, Jordan, to the International Police Training Center. It can be a frightening forty-five minute drive—both the road conditions and the drivers in Jordan leave much to be desired—and sometimes it seems as if Marsh has lost his way, until a sprawling group of buildings comes into view on the barren desert. Built by the U.S. State Department at a cost of $100 million (US) and covering 4.5 square kilometres, the heavily fortified base is where Marsh and nineteen other Canadian police officers are helping to train 32,000 new Iraqi police officers who are being deployed to replace war-weary US soldiers—a key part of America’s exit strategy.

While relations with Washington quickly disintegrated in early 2004 when Prime Minister Jean Chrétien refused to send troops to invade Iraq, this program allows Paul Martin to assure the US president that Ottawa is pulling its weight. Canada is spending $10 million on the training (a slice of the $300 million it has committed toward rebuilding Iraq) and isn’t the only country with cops in the desert. There are sixteen countries involved. For the Canadians (from nine different forces, they constitute the fourth-largest contingent here), the task must feel daunting, sometimes even futile. The increasingly beleaguered Iraqi police force has become a prime target of the growing insurgency, and these cadets may not last long on their country’s dangerous streets. “I doubt most of these recruits will survive a year,” says BC rcmp officer David Strachan. “They’ll leave, do other things, or go back to being farmers. Some will join the insurgents or get killed.”

Mornings are cold in the desert, a rare familiarity for the Canadians as they walk to meetings behind a wisp of their own frosted breath. Sandstorms and poisonous snakes are an occasional hazard, but minor ones compared to a potential terrorist strike. Marsh’s day begins with the same cautious routine: he pulls up to the maze of concrete barricades in front of the base, shows his ID, and then waits as his car is searched top to bottom for explosives. In January, insurgents killed ten Iraqi police officers when they bombed a training academy near Baghdad, a grim reminder of why pulling the cadets out of the war zone to a boot camp in Jordan makes strategic sense.

Marsh usually makes it through security by 7:30 a.m. to join a group of fifty firearms instructors in a prefab, air-conditioned office. The Swedes are dressed in dark blue uniforms, Jordanians wear blue camouflage, Poles paramilitary grey, and the Canadians are outfitted in blue and grey. The Americans seem to dress as they please. It’s Monday morning and the men, rubbing the weekend out of their eyes, are eager to attack the fresh hummus and falafel laid out for them. Bob LaChausse, a retired officer from Roseville, California, wearing khakis and a baseball cap adorned with an American-flag pin, points to a falafel, elbows me and bellows: “You like those lamb nuts? ”

The centre’s 300 instructors have trained over 10,000 Iraqi officers since early 2004. But the rush to get able bodies into police uniforms and ship them back to Iraq means the screening process isn’t altogether effective. There are constant rumours that terrorists have infiltrated police forces in Iraq.

I asked Larry Bray, an officer from Florida, if he thought there might be insurgents hiding among the cadets here in Jordan. “Oh, we know we have infiltrators,” he said. “We know we have al Qaeda here.”

If terrorists can’t easily strike inside the base, they have no trouble attacking the new recruits once they are deployed. Last year, hundreds of officers were killed in Iraq, including five in Ramadi, west of Baghdad. As the killers videotaped and spectators watched, the police were lined up on the street in broad daylight with their hands bound behind their backs before being shot in the head. The same week, insurgents killed more than twenty policemen in attacks across the country. It’s no surprise that Iraqi officers are quitting the force by the thousand, almost as fast as new cadets are trained.

With so many of their peers dying, you would expect the atmosphere at the centre to be sombre, if not outright paranoid. But there is a strange disconnect between life at the base and the war 300 kilometres to the east. “For eight weeks, they are out of a war zone,” explains Toronto police officer Andrew Raney, who teaches defensive tactics to the recruits. Or, as his colleague Ottawa rcmp officer Jeff Charette says, “They get three hots and a cot, and they don’t get shot.”

The classrooms and shooting ranges are a short car ride from the morning meeting. As Marsh drives across the wind-whipped base to the range, in what is either habit or steadfast regard for the rules, he uses his turn signals—the only officer, as far as I can tell, to do so. On the way, we pass a group of cadets marching on the road. They have been at the centre for a month, and seem proud of their ramrod posture and identical blue uniforms and caps.

The one exception is a huge man tramping along in a pink sweatshirt and gym pants (extra-large uniforms being in short supply). Later, when Marsh is teaching the men how to wear a police belt, he chastises the big man in pink for wearing the gear improperly, but then realizes the man’s predicament. “Oh, you’re wearing sweatpants,” he says accommodatingly. “I’m sorry. Carry on.”

Two of the cadets who walk into Marsh’s class are holding hands—an Arab cultural habit that puts them at risk, says Ottawa police sergeant Atallah Sadaka, who teaches general policing. “Iraqi officers always seem to die in groups, because they congregate in groups,” says Sadaka. “Back home we have what is called the safety space. You are at a distance from people so you can react. One thing we know about this country is that they are a close people.”

There are currently two jobs widely available in Iraq: police officer and insurgent. Like the rebels, the cadets reflect a broad range of Iraqi society: taxi drivers, carpenters, electricians, grade-school teachers, businessmen, and ex-military. Regardless of their backgrounds, they all seem to have a schoolboy’s regard for the lessons, whispering among themselves as Marsh delivers a lecture on target awareness. And when one of the instructors springs a pop quiz about the four cardinal rules of firearm safety, most consult cheat notes hidden under their desks. They are punished for this and other indiscretions by being ordered to do push-ups in front of the class. “Push-ups get the blood going and the brain working,” explains one of the instructors as a student sprawls on the floor. “This is not done to humiliate or embarrass you.”

While cadets are taught how to break down a door, disarm a suspect, and kick the living hell out of an attacker, they also learn the finer points of note-taking, how to properly referee traffic accidents, and how to deal with job-related stress. It is this part of the training, emphasizing brain over brawn, that officer Brian Readman from Edmonton refers to as “planting seeds” that will help Iraq build a professional police force. “Do we train them strictly as a paramilitary force or do we give them some of the philosophy and background as to what they should be looking for in future?” Readman asks. “Even if the 32,000 who end up being trained here can’t make a huge change in the next couple of years, their influence will come in the next generation of police officers.”

But Readman, along with every other instructor I interviewed, agrees on one point: eight weeks is not enough time to train a cadet. An rcmp officer typically receives six months of training, after which he or she is paired with a more senior officer for another six months. By comparison, an Iraqi cadet spends two months at the centre in Jordan and is then sent straight back into a war zone. And it doesn’t matter how badly these officers-in-training perform; short of chronic behaviour problems, they will be tested and retested until they all finally pass.

There is a constant pressure to get as many of these cadets onto Iraqi streets as quickly as possible, says rcmp superintendent Jean St-Cyr, an affable officer from Sherbrooke, Quebec, who is second- in-command on the base. “Iraq is still very much at war, and these police officers are put in a situation I feel is probably a military operation that’s ongoing, rather than a police matter.” He explains that the course is based on the “Kosovo model” used to train the nascent police force in the breakaway Serbian province. But Kosovo is relatively peaceful, and new police officers there are given on-site guidance after graduating, an impossibility in war-torn Iraq. “Are the cadets fully ready to face the situation in Iraq? I don’t think so,” says St-Cyr. “I don’t know if I would apply for a job as a police officer in Iraq.”

On day two of firearms training, morale in Marsh’s class suddenly perks up. The recruits had not been paid for October, but now a van arrives, carrying a large sack full of American dollars. The students abandon their studies as a thick-fingered Texan instructor doles out $140 each. One cadet, an eighteen-year-old economics student from Baghdad, looks pained at having to fold his hundred-dollar bill and two crisp twenties. After class, a few cadets, giddy and proud, ask to be photographed with their greenbacks.

The Iraqis’ love for U.S. cash, though, doesn’t translate into love of Americans. One of the English phrases cadets know well is “usa okay, Bush bad.” American range supervisor Grixbie Stephens says, “some students have actually threatened me.” All instructors are now required to carry loaded pistols on the firing range, after one of the students pulled a gun on his American instructor.

Thaér, a young Iraqi whose only outward sign of rebellion is the cadet cap he wears backwards, is openly hostile. “I hate American people. They invade my country,” he says. “If Canada was invaded by the U.S. with troops, what would you feel? ” I say I’d probably be resentful, but add that he is being trained on an American-funded base, largely by Americans, and is paid in American money. Thaér pauses, as though he hadn’t considered this before. “I hate every man that points a gun at me,” he finally responds in a torrent of guttural Arabic. “All Iraqi people refuse the invasion. I’m obliged to see American people, to deal with them. But the invasion is a big mistake.”

Serhan, another cadet, is a Sunni Muslim with greying hair and a sandpaper voice. Whenever he speaks of his family, which is often, his wallet comes out and pictures of his seven children tumble forth. “Right now, we are an occupied country,” Serhan says when asked about the Americans. “We needed them to topple Saddam’s regime. Now, we need them to leave as soon as we have stability and security.”

Serhan says insurgents have put a $5,000 price on his head. “I’ve had threats against me. I received letters from them telling me to leave the police. They say they will give me three chances to quit, and then they kill me,” he says. “But as Muslims, we believe our fate is written in the stars. I am not afraid of the dangers.” Try wishing him good luck, and you’ll be answered with a muttered “Inshallah,” which means, “God willing.”

The Western instructors find such fatalism maddening. As Grixbie Stephens points out, surrendering your fate to the stars sometimes means just plain surrendering. “Their hands were tied behind their backs and they were shot to death,” says Stephens about the assassination of twenty-one Iraqi police officers last November. “The reason for that is they gave up. The cadets don’t understand what fighting with your last breath means. They think there’s going to be some sort of mercy, some sort of leniency, and there’s not. If you are associated with the Americans, they’re going to hurt you.”

On January 10, the deputy police chief of Baghdad and his son were shot and killed outside their home. Not long after, the group of cadets I met at the Jordan centre graduated.

I tracked down Mohanned, who graduated from the centre in July, and was assigned to police his native Mosul, in Iraq. On the day I interviewed him, 3,000 of the 4,000-strong Iraqi Police Force in Mosul deserted their posts, with many of them, according to news reports, simply joining the insurgents.

“Our equipment is very poor compared to our rivals. We are having a very tough time resisting men with machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades, and rocket launchers. We’re visible targets,” Mohanned told me by phone, through a translator. The quality of the police training is very high, and the instructors are very professional, he said, “but eight weeks is not enough.”

Mohanned said it was love for his country, and the need for a job, that prompted him to train as a police officer. But like the thousands of others who have quit the police, he is no longer interested. “I do not feel secure for myself or my family,” he said. “When I see a man in a car, and that man is willing to explode himself, to die, what can I do? ”