When Sara Fung was hired as a clinical nurse specialist at a hospital near Toronto, she thought she was starting her dream job. Six months in, she was miserable. Every day felt like an episode of Survivor. “I had to find the right alliances,” she says, “or I was going to sink.”

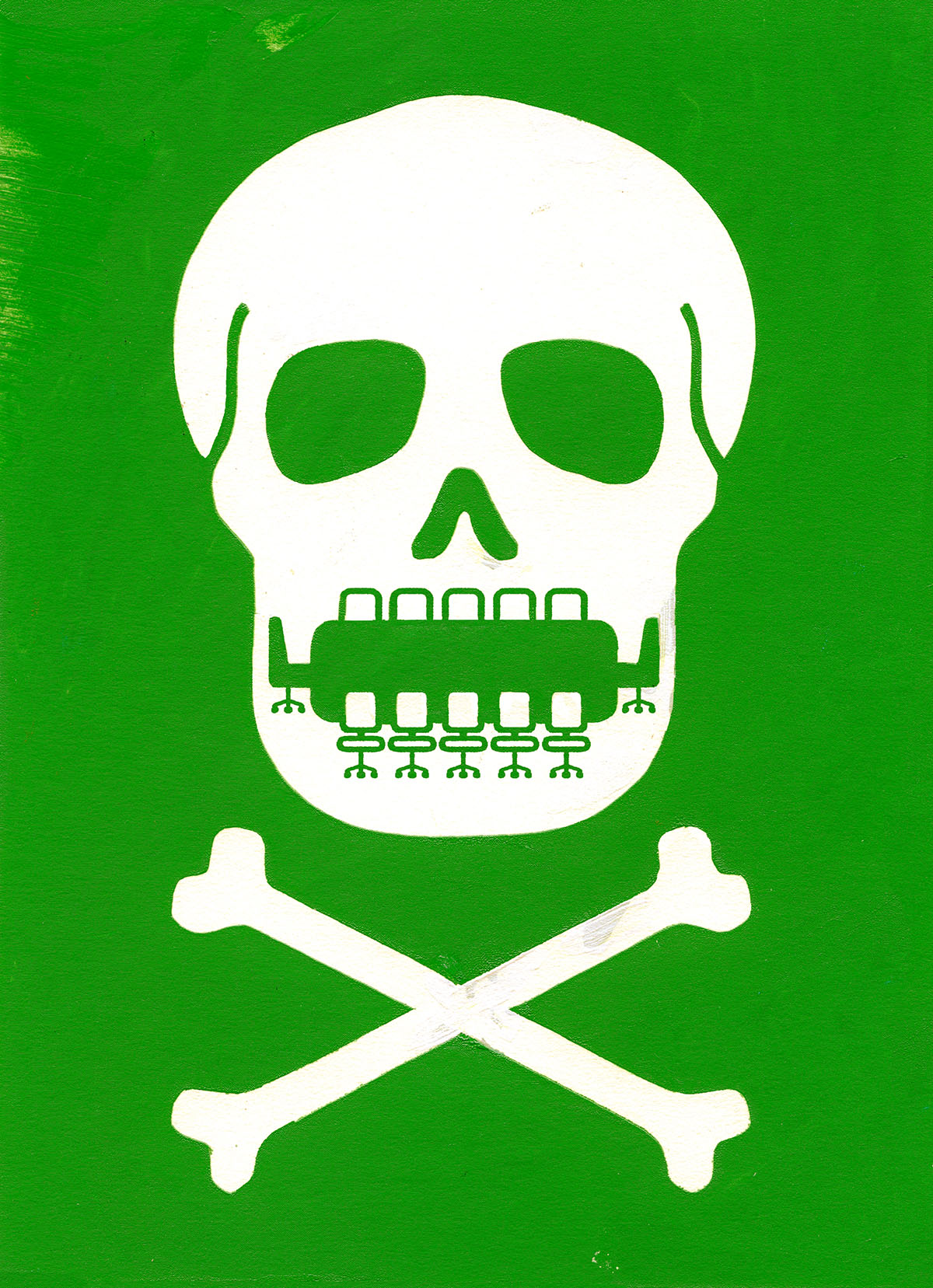

A manager Fung worked with was a bully, and the environment was generally hostile. During daily huddles with staff, the manager would reject most of her suggestions and discourage her from asking questions, and would sometimes call meetings intentionally excluding her. Fung recalls meetings in which physicians yelled at one another across the table, to the point that the administrative assistant didn’t know what to record in the minutes. The doctors rarely gave Fung a chance to speak and disregarded her expertise. It happened to others too. “A lot of high-performing individuals got stepped on,” says Fung. “They either stayed and kept their heads down, or left.”

Fung didn’t think complaints to the human resources department would go anywhere. At home, she would snap at her husband, her children, and her mother. She had trouble sleeping. To cope, she gossiped with the few co-workers she trusted. She eventually quit, moving on to another job that in many ways was just as demoralizing, where a manager would regularly give her specific instructions only to question her when she carried them out. Fung describes another director she worked under as a “toxic rock star”: someone who gets results but at the expense of the team’s well-being. Fung noticed that newcomers like her would start out with enthusiasm and a desire to improve things, but few lasted.

She has since built a business helping nurses grow their careers. She and a former co-worker host a podcast on health care; in certain episodes, they reflect on some of their worst experiences in nursing.

Some might counter that what Fung dealt with is typical of a high-stress environment, where tension among colleagues is expected. Those who can’t manage difficult co-workers or live up to their bosses’ standards are simply not cut out for their jobs. Maybe that’s true. Maybe we expect too much from our jobs. We don’t have to like our colleagues. Our bosses owe us nothing more than a paycheque.

Or maybe we shouldn’t accept misery at work as being normal.

Searches for the term “toxic workplace,” per Google Trends, have risen steadily over the past two decades. That lines up with increasingly publicized scandals involving high-profile figures. Then governor general Julie Payette resigned after a 2020 CBC report, and a subsequent independent review, found that she and her second-in-command had bullied and harassed staff by screaming at, belittling, and publicly humiliating them. In the past three years, allegations and complaints have abounded in TV and media, including at The Ellen DeGeneres Show (sexual harassment and racial discrimination), comedian Hasan Minhaj’s now-cancelled show Patriot Act (women of colour reported they’d been mistreated), the food magazine Bon Appétit (racism), the podcast Reply All (also racism—which came to light as its reporters investigated Bon Appétit), Jimmy Fallon’s The Tonight Show (culture of intimidation), and Fox News and Tucker Carlson’s show (sexist and antisemitic work environment). Last year, Mike Babcock, who once coached the Toronto Maple Leafs, was fired from his latest gig following an NHL Players’ Association investigation into reports that he bullied players—for instance, by demanding to go through their phones.

Then there are the less star-studded but equally alarming allegations of toxic workplaces. To name a few: Exxon’s offices in Texas, the video gaming company Ubisoft, the United Nations World Food Programme—one of the world’s biggest humanitarian organizations—and several municipal governments in Canada, including Edmonton, Winnipeg, and Montreal.

News reports tend to treat each case as a one-off, but there are some clear patterns. In several instances, employees allege that complaints to HR departments are either ignored, dismissed, or quashed—or spark retaliation. Problematic supervisors or co-workers are excused for their misbehaviours, especially if they’re men. (Anyone who’s heard something along the lines of “That’s just the way he is” about a colleague often enough will likely start believing and even repeating it.) Felicia Enuha, in an episode of her career management podcast Trill MBA, describes a toxic workplace as one that “allows the bad behaviour of one or a few to continue.” But what that looks like is subjective. Ashley McCulloch’s 2016 doctoral dissertation for Carleton University, one of the few studies that examine the psychological considerations of toxic work environments, draws parallels with the science of toxicology. A chemical can be harmless at low doses but becomes poisonous past a certain threshold. So it is with toxic behaviour at work.

By some measures, that poison is widespread. A 2020/21 survey, jointly conducted by researchers at Western University and the University of Toronto, found that 71.4 percent of respondents had experienced a form of workplace harassment or violence in the previous two years. In some cases, remote work models during the COVID-19 pandemic introduced new barriers to reporting harassment and prevented workers from accessing adequate support. The phenomenon isn’t limited to Canada: a 2021 survey by the UN’s International Labour Organization (ILO), Lloyd’s Register Foundation, and Gallup found that nearly one in five people worldwide experience psychological violence and harassment in their working lives. According to the report, many of those who faced discrimination because of factors like gender, disability status, or skin colour were more likely to have also experienced workplace harassment or violence.

“Within a capitalist system, the dynamic of worker and boss is already set up to be toxic.”

It’s not clear whether toxic behaviour is on the rise or if increasingly open discussions about mental health, sexual harassment, and racism, among other forms of discrimination, are shining a light on some fundamental flaws in the way we work. One could argue, for example, that professional hierarchies—often built on the conceit that promotions and advancements are merit based—provide a convenient facade for some of humanity’s worst impulses. Favouritism and nepotism can reward the undeserving, and discriminatory attitudes among those in power can hold back genuine hard work and talent. Inflated egos among some of those who rise through the ranks might drive them to mistreat those below them. There’s even handy business jargon that attempts to justify the inequity—say, for example, the concept of “managing up,” whereby employees are meant to, in essence, babysit incompetent or moody supervisors. “Even if your boss has some serious shortcomings,” one Harvard Business Review article advises, “it’s in your best interest, and it’s your responsibility, to make the relationship work.” (It’s not clear why exactly that burden should fall on subordinates, especially if they aren’t receiving a manager’s salary.)

Seniority-based workplaces, which reward those who are loyal to their employer, can also be problematic; workers who last long enough might arguably make the minimum amount of effort to maintain their positions at the top, leaving junior employees to do the heavy lifting. And commissions-based jobs invite the kind of noxious competition that makes the Netflix hit Selling Sunset so hate-watchable. (Toxic behaviour at work offers juicy tension for any number of films and shows—Succession’s characters seem to have bullying encoded into their DNA.)

Structural inequities aside, conflict in professional environments may be inevitable, since they often involve assemblages of people who otherwise wouldn’t choose to spend time together. Workplaces rarely invest in dealing with conflict, because profits tend to be prioritized over well-being. You could argue that the two go hand in hand: from a business perspective, work stress can result in lost productivity, absenteeism, medical costs, and high turnover, among other consequences. Given how much time we spend at work, how much self-worth many of us associate with our careers, and how job stress inevitably spills into the rest of our lives, the true damage may be impossible to quantify.

“When people tell me they’re in a toxic work environment, what they usually mean is they feel it’s causing them physical or psychological harm,” says Jeanette Bicknell, a workplace mediation specialist. “Even if you’re a good person or a good employee in a toxic workplace, you won’t thrive because . . . the workplace itself will make you dysfunctional.”

According to the ILO survey, just over half of those who experience workplace violence and harassment report what happened, and many are more likely to tell friends or family rather than turn to formal avenues. “Among survey respondents,” the report says, “‘waste of time’ and ‘fear for their reputation’ were the most common barriers.”

Some of that reticence may stem from the covert and insidious nature of psychological harassment. Micromanaging, giving inconsistent directions, and withholding crucial information from subordinates—as in Fung’s experience—are all forms of bullying. That hadn’t occurred to me until I spoke with Edmonton-based Linda Crockett, founder of the Canadian Institute of Workplace Bullying Resources.

When Crockett is called into a workplace for a consultation, she tells me, it’s usually because the client doesn’t know exactly what’s wrong, except that workers are unhappy. She starts by helping complainants understand what they’re dealing with. Many of them experience seemingly minor instances of harassment—small insults or derogatory comments—that they might dismiss at first, especially if they love their jobs. But then the problems add up, leading to some telltale symptoms: sleep loss, anxiety, even gastrointestinal disorders. Over time, she says, bullying targets—and she deliberately uses the word targets rather than victims—start to isolate themselves. They question their own behaviour, wondering whether they’re being too sensitive. They worry their complaints might be dismissed as run-of-the-mill interpersonal conflict.

For McCulloch’s study, she surveyed more than 500 employees and managers from thirty industries, with job titles as varied as academic librarian, police officer, CFO, and waitress. She found that the litmus test of toxicity lay in an organization’s tolerance for harmful behaviour: if employees reported being bullied, harassed, or otherwise abused, management did little to address their concerns.

I wondered if the long-term decline of overall union membership in this country had something to do with the seeming ubiquity of toxic workplaces. I haven’t worked in a unionized environment for most of my professional life, but I have heard friends and acquaintances describe labour organizing—and its focus on better working conditions, wages, and benefits for members—as a solution to workplace woes. But even unions can fall prey to a larger economic system that is itself toxic—riven with systemic features and dynamics that undermine the principles of unionizing.

Christina Hajjar was fired from her server’s job at Stella’s Café & Bakery, a Winnipeg chain, in November 2017 after complaining about her schedule. On the one-year anniversary of her firing, she posted about it on Instagram. Amid a flood of replies, Hajjar, alongside other Stella’s veterans, launched an Instagram account that posted screenshots, often anonymized, of solidarity messages from other workers at various locations. Some recounted daily injustices, such as managers insulting and fat-shaming workers. One post reported how a patron harassed a trans employee. Management did nothing about it and she was forced to quit. The most egregious violation, says Hajjar, was a case of sexual assault. When complainants made reports like these, management allegedly transferred the accused perpetrator to another location.

As part of their campaign, Hajjar, along with Amanda Murdock, Kelsey Wade, and several others who ran the Instagram account, demanded that Stella’s owners formally acknowledge the harm they’d caused and create an HR department. (Stella’s had introduced an HR position in 2016, but Murdock says the role largely consisted of issuing edicts—for instance, that workers shouldn’t take bathroom breaks during their shifts.) Within a few weeks, Stella’s owners apologized in a newspaper ad and video, and two of the most complained-about managers, including a vice president, were fired. By mid-December 2018, two Stella’s locations voted to join the United Food and Commercial Workers Canada Local 832 union. The triumph turned out to be short lived: both unionized locations shut down during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stella’s stated that the union’s demands—such as optional weekend work, minimum hours, and a $0.25 per hour wage increase for employees after one year—made pandemic operations unsustainable. It’s one reason, Hajjar says, the work she did to speak out will never be complete. (The company did not respond to a request for comment.)

“Within a capitalist system, the dynamic of worker and boss is already set up to be toxic,” she says. “Our labour has already been exploited. So what is toxicity if not exploitation?” It doesn’t have to be this way, says Hajjar, who hopes that it’s possible to have a job where the work environment doesn’t have to feel punishing.

Denise O’Connell thinks it can be. She now works in a corporate role at a company with a robust HR department. Before that, she had a long career in media and saw the difference unions can make. During one period when she worked in a unionized newsroom, she perceived better morale among her co-workers. At the very least, she says, they knew what time they could expect to leave work for the day. In other jobs, the hours could be long, stressful, and unpredictable.

She likens working in media to navigating playground politics: there are popular kids at the top of the hierarchy, and there are bullies who, she says, try to take back power when they feel powerless in other parts of their lives. Her newsroom co-workers harassed her. Some implied that, as a woman of colour, she’d been hired only because she met a so-called diversity quota. “I realized that the industry that I’m in just breeds a certain type of personality,” she says, “a certain type of ego.”

O’Connell once confronted a supervisor who had yelled at her at length for the way she’d labelled videotapes; her contract was terminated soon afterward. That was fairly typical, she says. In many places where O’Connell worked, there was no HR department or union to address complaints. It was worse when she shifted from news to reality and lifestyle television, where work tended to be contract dependent. She believes the precarity was by design. “When we talk about bullying,” she says, “it’s holding somebody’s livelihood over their head.” The transient nature of the work meant crews would disband after a few weeks, and there was never anyone on staff who dealt with interpersonal conflicts.

I didn’t realize that in accepting a certain level of toxicity at work, I might be helping to perpetuate it.

When she tried to help form a union among media workers, many of her colleagues were reluctant to sign on, fearing they might lose their jobs. She and some fellow organizers eventually received support from other media unions to help workers in their industry on a case-by-case basis—advising freelancers on how to negotiate their contracts, for example, or simply clarifying what rights they had.

Crockett tells me she’s perceived little difference between unionized and non-unionized environments in her work. She’s seen burnout among union employees, and some unions, she says, can be “toxic as hell”: their structures mimic the problematic hierarchies in many workplaces, and leaders are known to abuse their power. When I raised Crockett’s assertion, O’Connell conceded that for a union to be effective, its representatives have to reflect the diversity of those working in that industry.

Maybe that goes for all those who have the power to litigate or act on workplace complaints. It takes an informed perspective to recognize discrimination or harassment for what they are. And it takes a certain kind of leadership to accept that their work culture might perpetuate systemic inequities. That’s only possible when workplace leaders—especially at the highest levels—believe those systemic problems are real.

In theory, the federal government—this country’s largest employer—is loaded with mechanisms to protect workers. But just because those tools exist doesn’t mean they’re effective. Bernadeth Betchi had long felt underappreciated and overlooked in various government roles, including while working at the Canada Revenue Agency. She had a master’s degree in women’s and gender studies, yet she watched her white colleagues, some of whom had equivalent education and experience levels, get promoted ahead of her. “What makes it toxic,” she says, “is that you’re now working twice as hard, or maybe more, because you want to be noticed.”

After leaving the CRA, she began working as a communications assistant for the Prime Minister’s Office, completing duties primarily for Sophie Grégoire Trudeau, then took a position at the Canadian Human Rights Commission. Once again, she felt sidelined in her role and was dismissed when she asked about opportunities for a promotion. A manager told her she wouldn’t be able to handle a higher workload given that she had young children. Another time, she was told she didn’t have enough experience debriefing senior management. “I remember sitting there and thinking, ‘How much more “senior management” do you want than your prime minister?’” she says. Less than a year into her job, Betchi took a leave of absence due to stress.

In 2020, she and eight other complainants accused the CHRC of perpetuating racism and Islamophobia. The irony is hard to miss: the watchdog is meant to oversee complaints of harassment or discrimination in federally regulated workplaces. “If you’re a Black person, if you’re a racialized person, if you’re [part of a] religious minority, I would say don’t . . . bring your grievance at the commission,” says Betchi. “It’s not a safe place.”

That year, Betchi also became one of the representative plaintiffs who filed a separate claim against the federal government, seeking $2.5 billion in damages for Black employees in the public service. (A certification hearing for the suit is scheduled for early May.) In the statement of claim, Betchi describes a “poisoned” and “toxic” work environment. According to Nicholas Marcus Thompson of the Black Class Action Secretariat, Black employees across the public service have complained of reaching out to various employee assistance programs for mental health support, only to be told that the discrimination they were facing didn’t exist.

There have been previous class actions raised against federal government agencies, including against the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the Canadian Armed Forces, and the Department of National Defence, with external reviews describing what amounts to a toxic work environment for women and minorities. In recent years, Aboriginal Peoples Television Network has reported on allegations from Indigenous employees whose cultures had been disparaged at Indigenous Services Canada. In a 2021 APTN investigation, Mac Saulis, a Wolastoqey Elder, likened the environment of fear, harassment, and bullying to his experience at residential school.

A few days after my interview with Betchi, last March, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, which oversees HR services for the federal government, found the CHRC had discriminated against Black and racialized employees. According to a CBC report, it also reached the same conclusion in response to similar complaints filed by three federal public sector unions. (The treasury board, meanwhile, had itself been accused of having a toxic workplace culture the previous year.)

Four years ago, worldwide protests against anti-Black racism led to widespread efforts to introduce diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility initiatives—commonly known by the acronym DEI—to improve workplace culture. In many cases, the results have been superficial at best. They’ve allowed some workplace leaders to simulate the appearance of progress without making any meaningful change. It’s why there are still those who, like Betchi, find themselves having to prove over and over that they’ve been wronged. Some forms of toxicity may be systemic, but they’re perpetrated by individuals who usually don’t think they’re part of the problem.

In the fall of 2015, the news site Canadaland published an article about The Walrus, the organization that publishes this magazine. “The words ‘toxic work environment’ came up in many interviews Canadaland conducted,” author Jane Lytvynenko wrote at the time. Some described bullying, intimidation, and threats of firing if they spoke out.

I started at The Walrus less than a year later. I thought I was immune to what I considered to be typical hazards of professional life—that I could handle a toxic workplace because I’d survived others. I didn’t realize that in accepting a certain level of toxicity at work, I might be helping to perpetuate it. It can be hard to know where to draw the line between a demanding boss and a toxic one, between a high-pressure job and a damaging work culture. It’s harder still in an environment that’s perceived as progressive, where genuine passion drives the work—a place like The Walrus.

Staff turnover in the past eight years, along with a broader cultural shift, has made the environment feel more trusting than when I started. I know I’ll be listened to, and I know I’ll likely be believed if I raise concerns—admittedly a low bar for any workplace to meet.

“We’re really bad at helping people through difficult conversations,” says Julia Shaw, a psychology researcher based in London, UK. People on the receiving end of a complaint often don’t know how to react well, she says, even if they’re trained HR professionals. They might start, whether consciously or not, assessing whether their co-worker is too emotional, or maybe doesn’t look emotional enough, to be believed. That’s because most of us are wired this way. “We’re immediately going into deception detection mode, which is horrible for these kinds of situations,” says Shaw. “We bring our own biases.”

In 2017, Shaw co-founded Spot, a start-up that created an AI chatbot through which workers can report harassment anonymously. Shaw and her partners found that the uptake was highest in institutions with an existing reporting culture and Spot simply became a tool for better documentation. For Spot to have any effect, says Shaw, the desire for change “needs to come from the top.”

Yet many of those at the top are promoted to their positions with very little training in how to manage others. “There’s this assumption that this particular kind of soft skill is intuitive, that you can just pick it up along the way,” says Shaw. “It’s a skill you need to learn much like anything else.” It isn’t standard practice to train managers properly, because we tend to undervalue skills that are “associated with femininity,” she says, “like communication and stuff like that.”

I tried out a Spot demo Shaw sent me. I chatted with the HR bot about a made-up workplace conflict. It prompted me to share as much as I could recall, including who witnessed the incident and who else I told about it. Afterward, Spot emailed me a transcript of our exchange. Whenever I was ready to submit it along with any other complaints I filed, I could command Spot to compile my reports as PDFs and send them to my organization’s HR department—assuming there was an HR department. I’ve always worked in small newsrooms or nonprofits, places where human resources isn’t a fully staffed department but rather an add-on to one person’s job title. (I’m also lucky to be employed full time; many in the journalism industry are freelancers, who have even fewer protections or none at all.)

My situation is fairly common; Bicknell tells me the majority of her clients are in mid-sized organizations that are big enough to have personnel problems but too underresourced to handle them internally. Whatever the size of the workplace, she avoids singling out anyone who might be causing problems. “There’s the toxic workplace discourse, but there’s also the toxic employee discourse,” she says. “I try to get people away from that because . . . it’s often about systems and structures and not about bad individuals.” If an employee is consistently disrespectful to colleagues and consistently gets away with it, for example, that’s a structural problem.

But sometimes, there are obvious culprits. While Bicknell never recommends that anyone get fired, there are more strategic ways to go about it. “I remember, in one of my earliest trials, the boss saying from the beginning, ‘We don’t want to fire anyone, that’s not our culture. We pride ourselves on being loyal,’” she says. “But what message are you sending to the ten other people who work there? How are you being loyal to them?”

When Crockett delivers her workplace training, through workshops with staff and then leadership, she can usually identify, within an hour, who may potentially be a bully. And a common characteristic of bullies, she says, is that they tend to be dismissive of the training, suggesting it’s unnecessary.

She also works with respondents—those who have been accused of bullying—to help them change. In some cases, she finds they may have been accused wrongfully and are themselves targets of toxic behaviour. She says they’re sometimes dealing with layers of trauma that are triggered by high-pressure work environments, lack of supervision or training, and insecurity. “The system itself isn’t ready. The system itself is toxic,” Crockett told me when I first spoke with her. She’s since noted that workplaces with the right resources can successfully help people change their behaviour.

Still, she encourages those who experience workplace toxicity to prioritize their own recovery. “We cannot sit around,” she says, “waiting for justice to happen.”

Looking back, I can think of times when I unwittingly became an agent of toxicity. There are episodes that haunt me: Times when I privately dismissed co-workers’ complaints as being overblown. Times when I saw co-workers publicly belittled or sidelined and did nothing to stand up for them. I would tell myself that I was being professional or, worse, diplomatic. Like Fung, I’d channel my own frustration into gossip.

When I share this with Crockett, she tells me bystanders can feel as powerless as those being bullied: they don’t trust the leadership to address their complaints seriously. In other cases, they don’t want to risk becoming a target. “It’s valid,” she says. “Many people who speak up end up being bullied.” Some people don’t want to come forward because the bully might be someone they like. “And how do you report a friend?”

It’s not uncommon to find professionals who are conflict averse, she says. I confess to her that I’m one of them. “You have an obligation to deal with the fear of conflict,” she says, “because you have an obligation to report abuse.” This isn’t to imply that the root of toxic culture is all of us; that would be a cop-out for the leaders and systems responsible for how things run. But I do feel a responsibility for making sure that toxic behaviour, even if it’s common, never feels normal.

In the course of researching this story, I read plenty of articles on spotting and leaving toxic workplaces. None of the professional advice resonated as much as the experiences people shared with me, whether in interviews or in casual conversations. One takeaway that stands out is this: those who tell me they’re happy at work now often say they or their bosses have created an environment that they would have wanted when they were coming up in their careers. In other words, we need to become the role models we never had. That feels more achievable than trying to tackle systemic issues—and it might also be the only way to do so.

“I don’t think it’s inevitable,” says Bicknell when I ask her if workplaces are bound to be toxic. “I tend to see the unhappy workplaces, but I think there are happy workplaces out there.” The term she prefers is flourishing. “In a toxic workplace, there’s often gossip—people are talking about one another,” she says. “In a flourishing workplace, people talk about the work and they talk about ideas, and they’re energized and excited by their ideas, by the work, and by what they’re doing.”