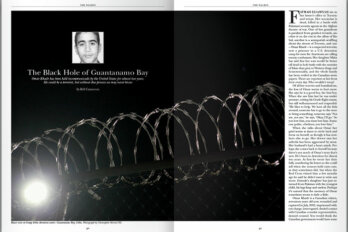

About-face Mark Jaccard, a research fellow with the C.D. Howe Institute, argues that we must not delay action on carbon emissions.[/caption]

The Accidental Activist

How an energy economist and former government adviser found himself blocking a coal train

The man accompanying me smiled.

“Good for you, sir.”

“Thanks. I appreciate your saying that.”

“They’re trying to build a coal mine near my parents’ place on Vancouver Island. We’ve got to stop this.”

“Yes, we do.”

“Now, watch your head, sir.”

With his final comment, the young policeman gently guided me into the paddy wagon—a difficult manoeuvre with my hands cuffed behind me. The seven other occupants ranged in age from forty to seventy, but I could only name one. I wondered what had brought each of them to the glistening seaside town of White Rock, British Columbia, to block a train carrying coal headed for Asia via Vancouver’s increasingly busy and expanding port. And I wondered if their stories were as unlikely as mine.

Two years ago, I could not have pictured myself engaging in such a desperate attempt to stop the country’s growing production and trade of coal, oil, and natural gas. As an academic, I have spent most of my career helping governments here and abroad design policies to reduce carbon pollution, just as I am now a consultant to the California Energy Commission as the state government implements an aggressive climate policy.

Six years ago, I had hoped to do the same for Stephen Harper’s newly elected government. In October 2006, the then minister of environment, Rona Ambrose, hired me to give policy advice, and a month later the government appointed me to the National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy. The advisory body was helping to produce the blueprint for Harper’s promise to reduce Canadian greenhouse gas emissions by 65 percent by 2050.

This was a major about-face. Leading up to the 2006 election, he had shown little interest in climate policy. Then Hurricane Katrina hit in August 2005. It ravaged and flooded New Orleans, killing over 1,800 people and causing $80 billion (US) in damages. Its chaotic aftermath continued to rivet public attention as politicians played blame tag for the slow pace of recovery. Meanwhile, the media portrayed the disaster as a harbinger of a hot future characterized by fiercer hurricanes and rising sea levels that would endanger increasingly vulnerable coastal cities.

The following year, with near-perfect timing, former US vice-president Al Gore released his climate documentary, An Inconvenient Truth. Prime Minister Tony Blair’s government in the UK issued the widely publicized Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change; and California, under Republican governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, passed the all-encompassing Global Warming Solutions Act.

At the time, Canadians ranked the environment above the economy as their primary concern, and like many politicians Harper was caught off guard by the rapidly growing public concern for the environment and global warming. With a minority government, he had to respond. Early efforts seemed legitimate: he publicly acknowledged the consensus among scientists that average temperatures must be prevented from rising by more than two degrees above pre-industrial levels.

As a member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which would win a Nobel Prize in 2007, I was well positioned to help design his new policy. In my 2005 book, Sustainable Fossil Fuels, I had argued that the fossil fuel industry might survive and even thrive if it invested in technologies to capture and store carbon. My point was that climate policies should focus on reducing carbon pollution, not on punishing the fossil fuel–dependent economies of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland. Harper seemed to get this, and I respected that he did not scapegoat Big Oil and Big Coal. No energy option is completely clean or green.

The Conservatives may have also liked that I was a research fellow with the C.D. Howe Institute, Canada’s market-oriented think tank, and that I had produced several reports criticizing the climate policies of Jean Chrétien’s Liberal government, which had concentrated its efforts on encouraging Canadians to voluntarily reduce their emissions. In my reports, I explained why policies had to restrict or levy a charge on carbon pollution to work. As Yale University’s William Nordhaus, one of the world’s leading climate economists, put it, “If a politician’s proposal does not raise the price of carbon, you should conclude it’s not serious.”

In 1997, Canada agreed to the Kyoto target, which gave us just thirteen years to make major reductions. When Chrétien neglected to immediately implement compulsory policies that capped or put a price on carbon pollution, I co-authored The Cost of Climate Policy (2002), explaining why we knew, even then, that Canada would therefore fail. In April 2007, Harper’s government asked me and four other economists to evaluate its study estimating the massive cost of trying to achieve the necessary 25 percent reduction in the few years left. To the dismay of environmentalists, we all agreed publicly with the report’s conclusions, which led popular activist David Suzuki to lament that we should stop listening to those “goddamn economists.”

We were just stating the obvious: de-carbonizing the economy takes time. To achieve significant reductions, we needed to start our low-carb diet right away and stick to it for many years, if not decades. (Crash diets are unhealthy for people and economies alike.) For these reasons, I also supported Harper’s decision in late 2006 to reject the target and substitute a more realistic one, a 20 percent reduction by 2020.

Even then, I had no reason to disbelieve his promises. Schwarzenegger had already demonstrated that a right-of-centre politician could take serious action to address voters’ climate concerns. In my own province of BC, Gordon Campbell’s pro-business government, which had shown no interest in climate in its first term, suddenly banned the future use of coal and natural gas to generate electricity, unless facilities were fitted with carbon capture and storage, forcing BC Hydro to cancel two proposed coal plants. I helped design this 2007 policy. Then Campbell hired me to advise his Climate Action Team, and in 2008 his government implemented North America’s first significant carbon tax.

Policy wonks call the period between 2006 and 2008 a “policy window”—an ephemeral opening for major initiatives, in this case to reduce carbon pollution. Some politicians may act decisively, for motives that range from sincere concern to crass political gain. Some may give the impression of imminent action while ragging the puck. Jean Chrétien had talked forcefully about his commitment but did very little. But Gordon Campbell had been a pleasant surprise, right in my own backyard. Why not Stephen Harper?

Then, in 2007, when he unveiled the substitute policies we had all been waiting for, the penny finally dropped. It was Chrétien redux, a resurrection of the same ineffective policies Harper had crucified less than a year earlier, this time cynically rechristened with the prefix “eco-.” The similarities were uncanny. As with the Kyoto target, Harper had chosen a deadline exactly thirteen years away—a safe distance for politicians. Like Chrétien, he promised never to implement a carbon tax. Like Chrétien, he had launched negotiations to regulate industry but conveniently failed to set a deadline.

Disappointed, though not entirely surprised, I produced another C.D. Howe report in June 2007 to explain—again—why Chrétien-Harper-style policies would never reduce emissions at the rate Harper had promised. Later that year, Globe and Mail columnist Jeffrey Simpson, fellow academic Nic Rivers, and I released the book Hot Air, in which we explained policy failures and how citizens could detect political insincerity. (If leaders do not immediately implement measures that cap or price carbon pollution, they are faking it.)

The financial crisis in 2008 closed the policy window, as public concern for the climate plummeted. Harper had to contend with another election in 2008, but Liberal leader Stéphane Dion made life easier for him by focusing on climate and promising a carbon tax—which Harper campaigned against as a job killer that would “screw everybody.”

From 2008 to 2011, Harper’s minority government focused on job creation but continued to express concern for the climate. In 2009, the prime minister even signed the Copenhagen Accord, agreeing with other leaders that humanity should not allow temperature increases to exceed two degrees, and reaffirming his commitment for major emissions reductions by 2050. (At the same time, he revised his 2020 target from a 20 percent cut to 17 percent, to match President Barack Obama’s goal for the US.)

Then, in 2011, Harper finally won a majority. He was now free to pursue his vision of this nation as a wealthy, fossil fuel–developing “energy superpower.” He still talks about his climate promises and his intention to enact regulations that will achieve his target. Meanwhile, it is full speed ahead with the fossil fuel agenda. In late 2011, Canada formally withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol. Environment minister Peter Kent justified this as avoiding financial penalties for missing our target; with no hint of irony, he blamed the “incompetent” Liberal government for setting a target without implementing policies to achieve it.

A few months later, the government eliminated the national round table, an institution with a twenty-five-year history of providing non-partisan sustainability advice to Canadian governments and the public. Foreign affairs minister John Baird defended this by criticizing the round table for repeatedly promoting a carbon tax (something it never actually did): “It should agree with the government. No discussion of a carbon tax that would kill and hurt Canadian families.”

Fossil fuel exports are now a key foreign policy priority, with Harper lobbying President Obama to approve the Keystone XL pipeline from the Alberta oil sands to the US, and criticizing the European Union and California for threatening to restrict oil sands imports because of the higher rate of carbon pollution caused by their production.

Domestically, the government laid off hundreds of scientists who monitor the health of our environment and the activities of industry. It “streamlined” the environmental review process to accelerate approvals of new oil and gas pipelines and coal port expansions. Minister of natural resources Joe Oliver justified these changes as a way of countering the delay tactics of “radicals” with “funding from foreign special interest groups.”

This is Canada today. The Harper government supports accelerating the extraction of fossil fuels from our soil, which will send more carbon pollution into the atmosphere. Meanwhile, that same government brazenly assures Canadians that it will keep its 2020 and 2050 emission reduction promises. But I know these assurances are worthless, for the very reason that Chrétien’s Kyoto promise was worthless. The 2020 target is only seven years away. Emissions have fallen slightly because of the global recession. However, the combination of economic growth and oil sands expansion will increase emissions. In a chapter of the Auditor General’s spring 2012 report, “Meeting Canada’s 2020 Climate Change Commitments,” his commissioner on environment and sustainability, Scott Vaughan, noted, “It is unlikely that enough time is left to develop and establish greenhouse gas regulations… to meet the 2020 target.” Instead, Canada is on a path to be “7.4 percent above its 2005 level instead of 17 percent below.”

These are risky observations, given that the national round table was axed after it reached a similar conclusion about Harper’s 2050 promise. In two round table reports, Achieving 2050 and Getting to 2050, we explained that Harper needed to quickly set a national cap on carbon emissions that would map out an annual decline from current levels to those he committed to for 2050. This is not rocket science: If you want to hit an emissions target, you set a cap that equals it. You have to start now, because a 65 percent reduction entails a complete makeover of our carbon-dominated economy.

A declining cap would drive the gradual market penetration of low-carbon technologies, such as biofuel and electric vehicles (the plug-in Prius and Chevy Volt, for example); heat pumps in buildings; and electricity plants powered by hydro, wind, solar, wood, geothermal, nuclear, and perhaps coal or natural gas with carbon capture and storage. All of these technologies are commercially available, but they will not penetrate quickly enough as long as carbon pollution is free or unrestricted. A cap changes that, which is why one was implemented by Europe in 2005 and another by California in 2012. In its 2008 election platform, Harper’s party promised to implement cap-and-trade, which it portrayed as different from Dion’s carbon tax. Yet it is running a national ad campaign claiming that cap-and-trade, now proposed by the federal

NDP, is a “job-killing carbon tax.”

Just as we can calculate the effect of a national cap to meet a national target, we can calculate the impact of a global cap on Canada’s fossil fuel exports. Harper set his 65 percent target for 2050 in line with a global effort to prevent a temperature increase that exceeds two degrees. Our current path leads to an increase of six to eight degrees by 2100, which scientists predict will acidify oceans, cause a massive species extinction to rival the five other great extinctions in the planet’s history, intensify extreme weather events such as droughts and hurricanes, and raise sea levels.

About 70 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions come from fossil fuels; production cannot increase if we are to achieve a major reduction in four decades. This means no expansion of coal production, nor of coal ports like the one near Vancouver. It means no new investments in the oil sands. And it means no new investments in oil pipelines, like Keystone XL and Northern Gateway. Many independent reports confirm this, including the two-degree scenario in the International Energy Agency’s 2010 World Energy Outlook. So why don’t more Canadians see that Harper’s fossil fuel agenda is breaking his climate promises, or that oil sands production is unethical?

The art of illusion depends on sleight of hand: Magicians distract your attention so you fail to notice the important action. Likewise, the developers of our coal, oil, and natural gas resources wish to distract us from the awful truth that their industry is destroying the planet as they grow rich.

Today in Canada, you cannot open a newspaper, listen to the radio, or watch TV without being inundated by ads informing you of the many benefits from oil sands development and the proposed Keystone XL and Northern Gateway pipelines. This industry is creating jobs and generating tax revenues for our schools and hospitals. Its donations support cancer research, disadvantaged children, community projects, scholarships, and so on.

Scan these ads and count how many times they explain why these projects are consistent with a world that keeps global warming below two degrees. Count how many times they even mention climate change. They don’t. Like any good magician, the fossil fuel industry directs your attention elsewhere.

The success of such campaigns depends on the human tendency to favour evidence and arguments consistent with self-interest and convenience. As writer and would-be politician Upton Sinclair used to say in his stump speeches in the ’30s, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it!”

Evidence of this propensity to delude ourselves surrounds us. The fossil fuel industry and its political allies can offer multiple rationalizations for why we should keep developing carbon-intensive projects. Such arguments are easily countered, but they are often drowned out by the fossil fuel media barrage.

We hear, “We are not going to stop using oil tomorrow, so these projects should go ahead.” This is backwards. If these projects proceed, we won’t stop using oil. But if we cap carbon pollution, sales of oil would start to fall today, as the plug-in hybrids and other low-emission vehicles capture a growing market share.

We hear, “We are just selling the coal, oil, and gas to the Chinese. We are not responsible for their emissions.” This is the sort of rationalization given by arms merchants.

We hear, “We need the jobs.” When the BC government cancelled one natural gas plant and two coal plants, the resulting hydro, wind, and wood waste projects created twice as many jobs. A similar effect would occur as we replaced gasoline and diesel with ethanol, biodiesel, and more zero-emission electricity in our vehicles.

We hear, “Canada contributes only 2 percent to global emissions, so there is no point making an effort until everyone acts at once.” Yet every year on Remembrance Day, Stephen Harper extols our critical role in confronting Nazi Germany’s global threat. He fails to mention that we actually contributed less than 2 percent of the Allied effort in World War II; one million Canadians served in our armed forces, compared with over 60 million who fought from the USSR, the US, the British Empire, China, France, Poland, and other countries. Even though we were only 2 percent of the solution, we have something to be proud of. We punched above our weight by joining France and England in declaring war on Germany in 1939, without knowing if and when the USSR and the US would join the cause. We did not wait for everyone to act simultaneously against a global threat, which is virtually impossible, but instead showed leadership. If we were to show leadership on climate change, we would join forces with California, Europe, Australia, and Japan. As the effort snowballed, we would use trade measures, if necessary, to bring other countries along.

In august 2011, over 1,200 demonstrators were arrested in front of the White House, in a protest against the Keystone XL pipeline organized by environmental writer and activist Bill McKibben. Arrestees included movie actors Margot Kidder and Daryl Hannah, as well as activist Naomi Klein. They also included researchers and academics such as James Hansen, a leading climate scientist who later wrote in the New York Times that the oil sands alone “contain twice the amount of carbon dioxide emitted by global oil use in our entire history.”

Albert Einstein once said, “Those who have the privilege to know have the duty to act.” We know the climate scientists are right. We know we have a propensity to delude ourselves for reasons of self-interest and convenience, even when the outcome may be devastating. And we know that our government is not owning up to the contradiction between its climate promises and its aggressive effort to expand fossil fuels. If citizens do not act to create a new policy window, effective policies will not happen.

Over the past five years, coal exports from Vancouver have risen by more than a third, and the port authority is considering an expansion proposal that could make it the largest coal exporter in North America. The coal trains pass through White Rock.

Like Hansen, I have knowledge. Like Hansen, I feel a duty to act. But neither of us has the money and resources of the fossil fuel industry. We do not have the media access of its political allies. What we do have is a willingness to make personal sacrifices in an effort to alert others to why this terrible situation threatens all of us, and our children, and why we all have a duty to act.

That is how I found myself blocking that Burlington Northern Santa Fe coal train. I was trying to answer the people who forty years from now will surely ask us, “What did you do when there was still time to make a difference? ”

This appeared in the March 2013 issue.