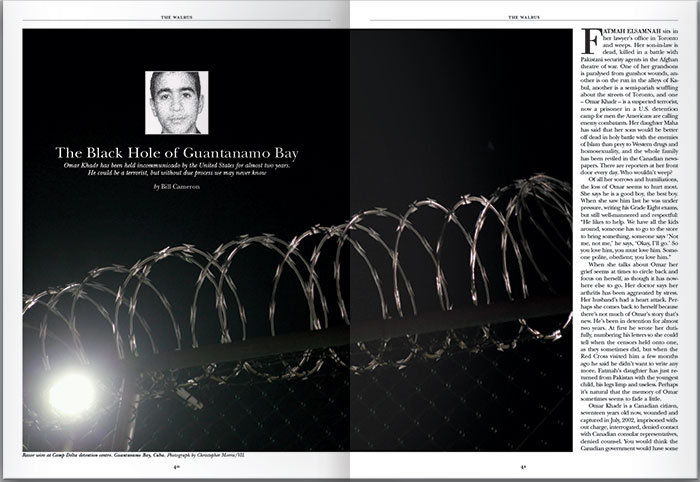

“The Black Hole of Guantanamo Bay,” Bill Cameron’s July/August 2004 article about Omar Khadr, is a discomfiting hit of post-9/11 nostalgia. The invasion of Iraq was barely a year old; the London Underground bombings were a year in the future. We were arguing over the status of a new category of persons, called “enemy combatants.” The central question of how much liberty we must sacrifice for our security was still a living debate.

For Canadians, patient zero of this psycho-legal pathology was Khadr, a Toronto-born teenager picked up in eastern Afghanistan in 2002 after a firefight with American forces. The then fifteen-year-old, badly wounded, was accused of killing a Delta Force operator named Chris Speer with a grenade. After a brief stay in the prison at Bagram, he was transferred to the US-run Guantánamo Bay detention facility in Cuba.

When Cameron travelled there two years later, little was known about the circumstances of Khadr’s detention. Was he being held alongside adults? How was his health? Had he been interrogated? Had he seen a lawyer? It is telling that the juiciest bit of news in Cameron’s story is that he managed to discover that Khadr had, in fact, been visited by Canadian “consular or intelligence” officials.

Khadr spent another eight years in Guantánamo. In 2005, he was charged with murder and attempted murder, but that tribunal was disbanded. He was charged again two years later, after which followed three years of legal wrangling, while American officials quietly pressured Canada to accept his repatriation. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled in early 2010 that his Charter rights had been violated, but bizarrely left the appropriate remedy up to the government. Meanwhile, his trial proceeded, and he eventually pleaded guilty at the end of October 2010, with the condition that he would serve one more year in Cuba, then return to Canada to finish his sentence. It turned out to be more like two years, as the Conservative government did everything it could to avoid bringing him home.

There are many more plot points to the story. But only upon rereading Cameron’s piece does the deeply perverse character of the narrative take shape. While Stephen Harper’s Conservatives are guilty of stalling on Khadr’s return, it was under the authority of Jean Chrétien’s Liberals that executive indifference to his basic rights first took root. When it comes to the war on terror, the disenfranchisement of Canadians is a thoroughly bipartisan affair. Recall that it was a Liberal government that introduced the hastily concocted anti-terrorism Bill C-36, soon after 9/11. This allowed for secret trials, pre-emptive detention, and expanded security and surveillance powers, with no sunset clause that would give Parliament occasion to revisit these new tools.

In 2013, the horror of the September 11 attacks has faded. The liberty-versus-security debate has been settled, firmly and unequivocally in favour of the latter. And despite Barack Obama’s promise in 2008 to close the prison at Guantánamo Bay, it is still open for business. Omar Khadr may have escaped, but the place remains a moral black hole, a dark rebuke to the conceit that a liberal society can defend itself while staying true to its most sacred values.

This appeared in the March 2013 issue.