Joseph arvay, Canada’s most powerful civil rights lawyer, spent much of last year trying to win Gloria Taylor a proper death. Time is running out.

His client has amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a fatal and rapidly progressive neuromuscular disorder, sometimes referred to as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Her muscles have already begun to atrophy. Her legs have given way and, inexorably, other body parts are failing. Eventually, she will lose the ability to stand, and then to swallow. She will be maintained by sets of tubes for feeding and waste. As her lungs give up, it is possible that her own body will choke her to death. Her brain, though, will remain sharp—so she will be cognizant of this betrayal.

Like the 3,000 other Canadians living with ALS, Taylor has no hope of surviving it. What she wishes for is a death with a modicum of grace, one that takes place before she is put through hell. It would be simple enough for her to orchestrate a suicide in the mobile home park where she lives alone in British Columbia’s Interior. Instead, with the portion of time allotted her, she chose to sit with lawyers, to travel to press conferences, to attend trials. Arvay delivered a massive—if temporary—victory this June, when the Supreme Court of British Columbia ruled that the laws banning physician-assisted deaths were unconstitutional, but the federal government appealed the decision a few weeks later. Meanwhile, Taylor is terrified of losing control of her bodily functions; she worries her family will bear witness to the final, undignified stages of her disease; she dreads the thought of her twelve-year-old granddaughter sitting vigil.

Arvay argues that physician-assisted deaths ought to be guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, even though a similar Supreme Court of Canada trial in 1993 decided that we have no such right. (Sue Rodriguez, the appellant in that case, allegedly killed herself with the aid of an anonymous doctor four months after the 5–4 decision.)

How, then, can Taylor, a grandmother in a wheelchair, earn a freedom that the highest court in the land has already denied her? As you read this, much of her suffering will already have come to pass. Whatever your beliefs on the matter, let us for the moment side with this woman. If we predict optimistically that Arvay will win her a merciful, physician-assisted death, how would it come about?

Arvay has a habit of proving the Supreme Court of Canada wrong when it comes to its dealings with the Charter. Most dramatically, he did this in 2007, when he convinced the court to overturn a trilogy of cases that denied unions the right to collective bargaining. (BC’s government had introduced legislation that let hospitals contract out union workers’ jobs, voiding earlier collective agreements; the province was essentially union busting en masse.) Peter W. Hogg, the country’s leading scholar in constitutional law, told me, “I was astonished when that case came out. I doubt that anyone but Joe could have persuaded the court that they had been getting it consistently wrong for twenty years.”

You could peg this ability to change great minds on Arvay’s master’s degree from Harvard University, where he studied constitutional law in the 1970s before Canada even had an equivalent constitution. Or on his unconventional past; in his twenties, he wanted to live in San Francisco and work as a “self-hypnotist.” Or on the car accident in 1969, during his freshman year at the University of Western Ontario, in London, which left him a paraplegic, using a wheelchair in a world that was suddenly full of obstacles. But perhaps the best explanation is simply that he really, really hates to lose.

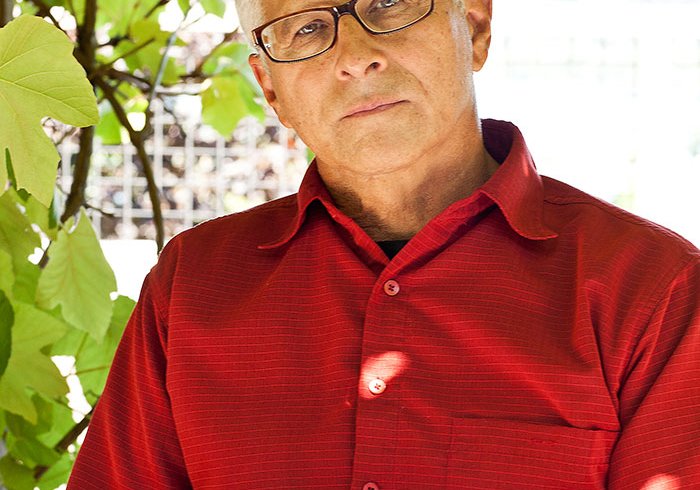

His office even sits in a confrontational building, on the thirteenth floor of an art deco masterpiece in Vancouver that rudely interrupts Hastings Street; the downtown grid twists uneasily around the structure. Inside, signs of workaholism abound. The walls are obscured by banker’s boxes, stacked five high like modernist towers and stuffed with files for Taylor’s case. His two desks are covered with papers and binders. During our afternoons together this past spring, he kept writing names on a pad, crossing out aborted attempts two or three times, in a dogged effort to get spellings correct. He is a handsome man of sixty-three, with a head of cropped silver hair, a tan from Mexico, and a lopsided grin, which he offers at incongruous moments, as though he were running a parallel conversation of his own. Each interview began with him saying he had told me too much of the personal the time before, and each interview concluded with him saying he had told me too little of the professional.

His real anxiety was directed at journalism itself: its layman’s approach, its cavalier summing up of complexities into neat narratives. A journalist is a generalist, and that position is anathema to Arvay.

His colleagues call him “a laser,” saying he is possessed of a mind that is “demanding, neurotic, beautiful to conceive.” Hogg says, “If Joe loses a case, which must happen from time to time, I think everyone will assume that there was just no way to win it.” Retired BC supreme court justice Ian Pitfield has laughingly complained that “Joe is like a hard-fighting trout on the line. He has to be reeled in sometimes, in order for his enthusiasm to be kept under control.” That laser brain has won drug users the right to safe injection sites, bookstores the right to import “obscene” material, and kindergarten teachers the right to celebrate same-sex relationships in their classrooms.

Yet behind the work, the work, the work lies a poeticism, a certain creative passion—perhaps a residue of his travels through San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury. Slippery terms in the Charter, such as “freedom of conscience and religion,” require expansiveness and engagement from their readers. After all, when a fifty-five-year-old Queen Elizabeth II sat down with Pierre Trudeau at an awkward little table on Parliament Hill, on that rainy April 17 in 1982, when she removed one black glove and signed our Charter of Rights and Freedoms into being (and church bells rang out across the nation, except in Quebec), the Queen did not grant us any particular, concrete rights.

Before the Charter, there was John Diefenbaker’s Bill of Rights, a 1960 effort that was quasi-constitutional and largely impotent. Under the bill, Canadian courts still relied on Parliament to effect changes—which, in retrospect, looks like asking children to please set their own bedtimes. Trudeau’s Charter broke free of that mess, by entrenching in the Constitution political and civil rights and freedoms (such as freedom of expression and association, the right to vote and to live anywhere in Canada, the right to security of the person, and so on), and by pointedly limiting government power. Instead, the Charter declared that some matters were beyond the jurisdiction of elected officials and needed to be parsed out in the courts. So what the Queen really gave us on that April day was an invitation to battle.

Arvay has thrived in this combat zone. He earned his Queen’s Counsel standing after ten years at the bar, shocking many with his youth. (The honorary title is bestowed upon lawyers who have made an exceptional contribution to their profession; most QCs have a quarter-century of experience under their belts.) By 1990, he left the government’s employ, where he had found himself siding with the citizens he was supposed to argue against, and launched his eponymous firm.

While Arvay flourished, the rest of Canada remained mired in confusion. Shortly after the Charter’s signing, the Globe and Mail worried that it would have “no practical effect.” Others were flummoxed by the Charter’s ability to transfer so much authority from elected officials to unelected judges. The police insisted that the Charter would make it more difficult to draw out damaging or incriminating statements, forcing them to resort to other investigative tools, such as wiretapping. Deputy Chief Thomas Flanagan of the Ottawa Police Service told the press, “Nobody can tell us for sure what the heck the Charter means.” Did the Charter let people buy dresses on a Sunday? Were convicts allowed to vote? Could seniors still pay reduced fares on buses? What was the limit of freedom, now that it was up for debate? A group called Measure Canadian, for example, used the Charter to challenge the tyranny of the metric system. Equally unsettling was the sudden advertisement of rights that most Canadians assumed they already had. These broad-based uncertainties continue today: this past spring, Ecojustice and the David Suzuki Foundation appeared in court to ask why our Charter cannot guarantee Canadians a healthy environment. To date, we have no right to clean air, land, or water, unlike citizens of France, Norway, and ninety other nations.

It is not unreasonable to ask that a state’s guiding document be clear. But what Arvay understood, better than nearly anyone else in 1982, was that the Charter does not in itself mean anything. Rather, it lays out principles. And principles mean nothing until somebody starts arguing about them. In Taylor’s case, for example, Arvay has asserted that she should have the right to a physician-assisted death under Section 15 of the Charter, which promises equal treatment under the law. Suicide is legal in Canada, so people with disabilities should have access to it. But he is also calling up Section 7, which promises the “right to life, liberty and security of the person,” using the highly creative logic that—since those with degenerative diseases may take their own lives earlier than they want to, to avoid being trapped in a state where they cannot complete the act—the current law damns Taylor to a more abbreviated life than the promise of a physician-assisted death would. In action, the Charter is a poem, open and ambiguous, and, knowing that, Arvay has become its most powerful reader. “The Charter’s broad language is precisely its genius,” he says.

This allows the Charter’s meaning to move, grow, or utterly change. Our rights are shape-shifters. In the 1930s, the fantastically named US judicial philosopher Learned Hand wrote that people should “have no confidence in principles that come to us in the trappings of the eternal.” Liberty exists not in a static document but in our ever-evolving hearts. Too much love for a fixed decree is what has made America into a legal backwater: “The US Constitution appears to be losing its appeal as a model,” conceded a recent study from Washington University in St. Louis and the University of Virginia. Among democracies in the rest of the world, the influence of the US Constitution is in decline. By comparison, Canada’s Charter is expansive. We are the envy of the legal world. Canada is now acknowledged as a “constitutional superpower,” and is given credit for inspiring bills of rights in New Zealand, Hong Kong, South Africa, and elsewhere.

That free-range quality has allowed Arvay’s humble law firm, with breathtaking speed, to lengthen the list of Canadian rights and freedoms. He has perhaps influenced Canadian life more than any judge or politician has done. As though to raise an eyebrow at his own success with the Charter’s poetics, he has hung a drawing of Don Quixote in his waiting room, and “quixotic” isn’t too bad a description for Arvay—until you realize that his idealism often yields astonishing, bona fide victories. How does he do it?

Many have tried to explain Arvay’s success. Craig Jones might have a better chance than most. A professor of law at BC’s Thompson Rivers University, he previously worked for the provincial attorney general’s office, and has disagreed with Arvay about the legality of polygamy, and whether the Vancouver Rape Relief Society could prevent a transsexual woman from volunteering. Although the two generally get along, they have blown up at each other a few times. Jones says this is due to Arvay being “so tenaciously focused on his clients and the case.”

Still, he admires Arvay more than most opposing counsel would, and for good reason. While earning his LLB at the University of British Columbia, Jones was arrested after joining a student protest against the 1997 APEC summit in Vancouver, which placed his future career in the balance, and it was Arvay who represented him at a public inquiry.

In a café across from the Vancouver Law Courts building, Jones keeps looking out the window, weighing his head back and forth. “Joe’s very hard to prepare against,” he says. “He doesn’t have a predictable strategy. Sometimes he’s extremely scattershot. I guess his greatest gift is that he has the brilliance to throw all of the marbles in the air and know he’s the one who will catch them.”

Jones smiles, but he continues to look out the window as he talks about Arvay’s defence of North America’s first legal, supervised safe injection facility, Insite, located in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, one of the country’s poorest neighbourhoods. “He had fabulous evidence on his side,” Jones says. “But the trick was this: he mustered that evidence into a moral argument so powerful that when the Supreme Court of Canada heard it, there was just no question whether Insite would be closed. He honed things down to a spear tip and went straight to the heart.” Finally, he looks at me and finishes his thought: “Napoleon said that God is on the side with the best artillery. And that’s Joe.”

Arvay is a laser. A trout. A God-blessed militant. It’s a testament to his prowess that lawyers on all sides turn mushy when describing him. Still, during my afternoons in his office, as he unpacked the story of his career, three prosaic elements did emerge: timeliness, firepower, and standing. And this much became clear. For Taylor to win her right to die, she would need all three.

Any literary critic will tell you that the meaning of a poem changes with time: this year’s patriotic hymn is next year’s colonial garbage. Likewise, our poetic Charter can produce rights today that it could not yield even five years ago. One of the great ironies in Charter cases is that not all equalities are created equal. Basic rights must come first, and only they can give birth to more complex ones.

Case in point: In 1994, James Egan, a gay man, found himself on the bottom rung of the equality ladder, fighting for the simple right not to be discriminated against; the Charter did not specifically mention sexual orientation. He teamed with Arvay to fight for the spousal allowance denied to his partner, John Nesbit, by the Old Age Security Act. Today this seems like an obvious right, but in the mid-’90s, a period marked by the ravages of AIDS and the attendant paranoia, Arvay realized that gay equality cases always turned into heated moral affairs. One day during the trial, he sat his clients down and told them, “You know, the reason gay couples have such a hard time in court is never going to be articulated. But I think the reason is that as soon as I get up and talk about gay rights, people instantly think of anal penetration.”

Egan leaned across the table and exclaimed, “But I don’t even do that!”

Arvay led the court past its discomfort about gay sex and toward basic issues of fairness. In its ruling, the Supreme Court of Canada affirmed for the first time that the Charter prohibited discrimination based on sexuality. The groundwork had been laid.

A few years later, James Deva took Canada Customs to court for seizing material bound for Little Sister’s, a gay bookstore in Vancouver. The stakes were markedly raised; this time, gay sex was very much at issue. Canada Customs declared obscene any depictions of anal sex, sado-masochism, or erotic bondage. The case, as argued by Arvay, became unlike any obscenity trial in the country’s history. Earlier lawyers had fought such cases this way: “I find your expression disgusting, but I will hold my nose and defend your right to express yourself.” When Arvay met with his client at the offices of the BC Civil Liberties Association, Deva asked, “How do you feel about fist-fucking, Joe? ”

“Well, I don’t know a whole lot about it,” replied Arvay. “But I’m certainly willing to investigate.” Deva decided he had a winner, and Arvay left the meeting with an armful of banned books.

He met with the authors of what Canada Customs had deemed as “filth,” including such highly literate thinkers as sexual rights activist Pat Califia and novelist Jane Rule, to build a case that these books and images constituted integral parts of a culture. During the trial, he slept just a few hours a night and, in Deva’s words, turned the courtroom into “a beautiful theatre.” A landmark victory followed: the Supreme Court ordered Canada Customs to stop harassing gay bookstores. In six years, Canada had moved

from “We won’t hate you” to “We will tolerate your culture.”

There is an even higher rung of equality, though: the right to be celebrated. When James Chamberlain, a primary school teacher in Surrey, BC, introduced material in his classroom that normalized same-sex relationships (picture books such as One Dad, Two Dads, Brown Dad, Blue Dads and Asha’s Mums), the local school district bowed to religious pressures and banned them. Arvay’s 2002 case before the Supreme Court moved the goalposts yet again. Given that the country endorsed gay relationships, they would have to be discussed in a positive manner in schools—even in kindergarten classrooms.

Only then, in the summer of 2005, could the pinnacle that is gay marriage be approached, far beyond the basic benefits of the state (Egan’s Old Age Security). Canada became the third country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage, which, as Arvay says, “gave the state’s imprimatur to the most significant kind of relationship you can have. When the state was required to give gay couples that badge, it was the culmination of a long journey.”

This queer ladder of rights typifies other rights battles; each victory on a given terrain makes the next acreage of liberty “vulnerable” to attack. The Egan case, which dealt with cold-cut money issues, became “the thin edge of the wedge,” says Arvay, “that allowed gay marriage to come through.”

Whichever rung we dangle from, it is easy to forget we are, indeed, dangling. Lawyer fees are such that almost no individual has the resources to further his or her own rights case, and this question of costs has become a near-obsession of Arvay’s. “There will only be some measure of justice in this country,” he says, “when governments are forced to pay for the challenges brought against them.” For all his successes, one glaring omission remains: he has yet to prove that access to the Charter’s promise—meaning funding—is itself protected by the Charter.

The Trudeau government established a funding initiative in 1978 that eventually became the Court Challenges Program; for decades, it provided money for equality cases when applicants had no resources. Then, in 2006, Stephen Harper’s Conservative government cancelled the program. The Canadian Bar Association called the Tories’ actions an assault on Canadian democracy. In an interview with the Ontario legal periodical Law Times, the CBA’s second vice-president said, “The cuts are tantamount to silencing a very marginalized group of Canadians.” While it lived, the CCP provided funding for two-thirds of all equality cases at the Supreme Court level.

The Conservatives couched the end of the Court Challenges Program in cost-cutting rhetoric, but the rationale is more likely ideological. The CCP cost just $2.75 million each year—a minuscule fraction of the reported $100 million the government spent on missiles alone in 2007, the year following the cancellation of the CCP.

For conservative Sun Media personality Ezra Levant, the demise of the CCP was a happy day, and he crowed in Canadian Lawyer magazine that it meant the end of such “counter-cultural” activities as winning prisoners the right to vote. In his words, the CCP “fed an awful lot of activist lawyers who otherwise couldn’t get funding for their pet political projects.”

Not everyone, though, feels that a lack of cash ought to signal irrelevance. To David Eby, executive director of the BC Civil Liberties Association, a Canada without programs like the CCP is one where the wealthy simply have more rights than the poor. “Today you have these rights, but you must go up against the bottomless resources of government lawyers,” he says. “They routinely make applications for a judge to dismiss a constitutional interest lawsuit, even before it begins. They’ll argue that the case isn’t recognized by the law, that the parties don’t have standing, that some technical default has taken place. This is an established tactic that has been emphasized in their professional development programs. It’s a bald attempt by a well-resourced opponent to exhaust resources. It’s bullying, and it’s directly opposed to any notion that the Crown is concerned about access to justice.”

At the provincial level, legal aid programs are also stretched for funding, and it has become difficult for them to find money for non-criminal cases. There is, in other words, an inherent paradox in the struggle for Charter rights: those who most desperately need to make use of the Charter, the disenfranchised, are exactly the people for whom court costs pose a barrier. Indeed, the timeliness needed to win a Charter case, as seen in the same-sex marriage scenario, is nothing without a second, major ingredient: money for lawyers. Firepower.

In the case of James Deva and his gay bookshop, even after the store exhausted its scant funds to defeat Canada Customs in 2000, the government continued to seize books at the border, necessitating another costly court case. Arvay argued for advance funding from the government; essentially, he was advocating for the right just to fight the battle. On January 19, 2007, he was forced to call Deva and explain the sixty-three-page decision. Funding would not be forthcoming, and so the case was dead. “All of our work,” says Deva, “was for naught.”

“You have to get downright Zen about these things,” says Arvay. “The odds are against the citizen.”

At a dinner following the ruling, Deva said that he figured he owed Arvay more than $100,000 in legal fees. Arvay told him, “No, Jim, you owe me nothing.” It was an act of grace, but also a practical kindness: Deva didn’t have the money to give. In the absence of government support, the firepower that is Arvay has become almost entirely a function of one man’s goodwill, hardly a solid grounding for civil liberties.

Perhaps the ultimate example, though, of our need for such initiatives as the Court Challenges Program is the 2011 case regarding Insite, Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside injection site, where drug users could obtain clean needles and inject under medical supervision. The federal government wanted badly to shutter Insite, and went to enormous lengths to discount its value, going so far as to wilfully ignore academics whose research reported that Insite saved lives and stopped the spread of HIV/AIDS. Former health minister Tony Clement called the institution—which every concerned party except the government approved of—“an abomination.” Of course, those drug users could never have funded their own champion in this battle. Arvay again completed the work pro bono.

He recalls that, mid-trial, Justice Ian Pitfield used his fingers to indicate quotation marks around the phrase “addiction is an illness.” He finished the thought with “Some might say that this is recreational.” The next day, Arvay challenged that notion, saying that the concept of addiction as an illness was beyond controversy. He invited the opposing counsel, John Hunter, to concede the point. Hunter stood and simply said, “I’m happy to say that we accept addiction as a disease.” The government had not agreed with this point at the outset of the trial.

“That was the moment,” Arvay says. “The moment it stopped being a moral question and became, like birth control, about access to health care.”

Usually, on the morning of a decision, he phones the court in his pyjamas for news of the ruling. With this decision, he was invited to Insite. He thought there might be a few people assembled; instead he found 300 drug users, advocates, and journalists standing in the street. He got on the phone at 6:45 a.m. and reported to the crowd that the highest court in the land had protected the facility. Looking back, Arvay says, “For some of these people, it was the most important day of their lives. This was life and death.” It was also, arguably, Harper’s largest and most embarrassing courtroom loss; he had, as Maclean’s noted, “swung and missed.” Despite his comfortable majority, the judiciary had drawn a firm border around his powers.

This is a limited victory for Arvay, though. Even while a growing number of reports indicate that supervised injection sites help both drug users and cities, Harper and Toronto mayor Rob Ford remain ideologically opposed to the creation of a similar site in Toronto, which is home to between 9,000 and 13,000 intravenous drug users.

As for Taylor and her death with dignity case, her struggle is beyond a political stance. For her, the thirty-six three-inch binders and 116 affidavits that make up her trial record stand apart from any partisan argument. And by the time Arvay’s work wends its way to the Supreme Court of Canada, she may not be alive to hear the ruling.

I saw her briefly, after the BC court announced its decision to allow physician-assisted deaths. She wore purple, with silver earrings in the shape of butterflies, and she seemed hopeful that the decision would not be appealed. I wondered whether this was blind

faith, or whether nobody had told her how unlikely that was.

Justice Lynn Smith had granted Taylor a constitutional exemption anyway, which meant that she, and she alone, could carry out her assisted death before the courts complete their ponderous proceedings. A right, it seemed, might precede a ruling.

I thought she would look happier, or at least vindicated. But her lips quivered as she spoke of the others, those who still await a higher court’s decision. There were moments of release as she brought a water bottle to her mouth with two hands that had turned to unworkable claws (she must drink as she talks, because her throat is giving out). She said, “We changed Canada. We made a difference. This brings me great solace.” Some three weeks later, the federal government announced its objection to Taylor’s constitutional exemption, which it is attempting to have revoked.

Seeing Taylor, though—so weathered and so optimistic—it was obvious that her struggle has only partly been about the question of her own death. She has made a stand for others, which became a defining part of her life. When health authorities tried to transfer her ailing father away from family members in his final days, she refused to let that happen. When her son received poor care after injuring his knee, she advocated for more hospital beds in Kelowna, BC. When she learned she had no voting rights, as a non-native living on reserve land, she ran for a position on the Westbank First Nation’s advisory council, to have a voice. She is a woman who intends to be counted.

This conviction is key, if her new right has a chance of advancing. She needs more than just the timeliness of the same-sex marriage case and the firepower of the Insite case. There is a third and final component to winning a new right, and that is “standing,” the ability to convince the court of your connection to, and harm from, a given law. One cannot, for example, dismantle the laws that ban brothels unless one has a real live sex worker on the team. Standing is the quality that takes an abstract issue and makes it personal. Without it, the fact of timeliness and the amassing of dollars for lawyers mean nothing.

There is standing in every rights battle. Some importunate quality inside of James Chamberlain made him feel compelled to bring Asha’s Mums to school. A kind of stubbornness made James Deva refuse the censorship of low-level government employees. There is a righteous element, too, in the drug users at Insite, which made some of them reject what they were told by far more powerful authorities than themselves. All of these disadvantaged people conceived of rights that did not exist except in the obscure, poetic promise that is the Charter. They were ordinary citizens made special by circumstance and will.

Taylor believes she is next in line. She has pre-arranged her cremation. She has chosen songs for her memorial service and written her own eulogy.

Liberty is not a one-way street. It is often insinuated that rights expand and become more difficult to dislodge over time. But is this so? David Eby points out that “the day before September 11, nobody would have thought that Canada would support extended detentions without charge or secret evidence trials. But we now have both.”

Professor Hogg, taking the long view, says, “One can see a tendency for each right to gradually expand its protection. The process is incremental, but the ratchet tends to work in that direction, not the other way. Joe understands this, and he shows the court why his client’s case is the logical next step from the last decision.”

Back at the café by Vancouver’s law courts, Craig Jones drains his coffee and stares out the window again. “But what is progress? Whose progression are we talking about? We all think we’re progressives. Marxists will tell you that all rights litigation is inherently distributive; if you give a right to one group, you’re taking away something from another.” His head rocks back and forth as the idea settles in. “But then, my citizenship is enhanced with the more rights my fellow citizens have. Rights must be synergistic. I guess I do think there’s progress.”

The pressure, though, is constant. All Canadian governments are, almost by nature, hostile to the Charter. “They certainly like to hold on to their power,” says Arvay, laughing while he rifles through a stack of papers in his office. “And they certainly don’t like it when you tell them they don’t have that power at all.” That said, Harper’s run-ins with the Charter have been prodigious. The Conservatives are especially piqued by the Charter’s undemocratic quality, its making of philosopher kings out of judges. In the lead-up to Harper’s first term, at a March 2005 Liberal Party convention, folks walked around with buttons that read, “It’s the Charter, Stupid”; and, later that month, the Conservatives hosted their own convention with buttons that replied, “It’s the stupid Charter.” Earlier this year, the government was criticized for marking the Charter’s thirtieth anniversary with little fanfare, nothing more than a news release.

Three decades after the Charter was signed, Arvay’s work has, surprisingly, become more charged and more relevant, because the laws that have emerged from the current government are so often accused of being unconstitutional. For instance, the Lawful Access bill is denounced as Internet spying; the Safe Streets and Communities Act contains mandatory minimum sentences that will increase incarceration rates, especially for Aboriginal people; and new legislation will privilege immigration applicants from “safe” countries, cut off refugees from health care, and empower the government to detain refugees for as long as twelve months. All of this will be subject to multiple challenges, provision by provision. Rather than learn from these corrections, though, some lawmakers now seek to “Charter-proof” their work, as though the Charter were a stumbling block to get around.

It is well understood that powerful forces on occasion seek to engineer an unconstitutional Canada. What’s astonishing, though, is that our defenders are people like Arvay, working with a small staff and no guarantee of pay. Our defenders, too, are ordinary people like Gloria Taylor—those who tenaciously ask, demand, plead, and fight for a finer reading of the poem that governs our lives.

This appeared in the October 2012 issue.