Books discussed in this essay

George Sprott: (1894–1975) by Seth

Drawn and Quarterly (2009), 96 pp.

The Collected Doug Wright: Canada’s Master Cartoonist (Volume One) by Doug Wright

Drawn and Quarterly (2009), 240 pp.

The Complete Peanuts: 1950 to 1952 by Charles M. Schulz

Fantagraphics Books (2004), 343 pp.

Palookaville was the title of the comic book series, and right away we should have known that its creator, Seth, was up to something. The word was as vague as the names of the other small-press comics springing up in Canada at the time, but where Yummy Fur promised tactile surrealism and Peepshow and Dirty Plotte connoted sex, what did Palookaville tell us? Marlon Brando used the term in On the Waterfront, but it was decades out of date by the time Seth claimed it for his solo debut in 1991. For devotees of cartooning history, the word might also recall Ham Fisher’s pugilist, Joe Palooka, but in any case it conjures up a fanciful middle-of-nowhere populated by marginal has-beens like Fisher’s cartoon hero or Brando’s dockworker. This Palookaville is Seth’s town, full of cast-offs, outmoded relics from the past, and the arcane history of comics, all located somewhere at half a remove from our own Canadian reality. Although his characters may visit or come from Chatham and London and Guelph and Strathroy, Palookaville is the small Ontario town of the mind where they—and Seth—have actually lived for the past couple of decades.

Seth’s output is more broad than prodigious, but remarkably consistent in its melancholic concerns with time, comics, and places, specifically Canadian ones. It encompasses everything from comic books to book design, from museum installations to architectural models, along with the odd foray into critical prose. Lately, however, he has increasingly channelled his creative energy in one direction. So, to start with, recent issues of Palookaville describe an inept salesman’s memories of failure in a large Ontario town, not unlike London or Kitchener, called Dominion. The artist has also crafted dozens of cardboard models of the town’s buildings, which have been displayed in galleries in Waterloo and Dundas. He has privately sketched out, in images and prose, the town’s history, its architectural motifs, and its people. One of them, a washed-up Arctic explorer, provided the basis for his recent contributions to the New York Times Magazine’s Funny Pages.

The Times Magazine strips have been collected and expanded upon in a book called George Sprott: (1894-1975), released this month by Seth’s Montreal publisher, Drawn and Quarterly. It’s an appropriately large showcase for one of the smoothest hands in the business, the brush strokes precise and hefty, the colours muted, the page design bold and rhythmic. Told in the simplified staccato of Seth’s sketchbook cartoons, rather than the more languorous style of his Palookaville comics, the story of George Sprott slowly emerges from dozens of single-page strips and occasional, sepia-toned multi-page flashbacks. An elderly local TV host who still dines out on the northern excursions he made in his thirties and forties, he is now forgotten, stumbling toward death. Seth describes his protagonist’s decline in documentary style, providing omniscient narration along with the contradictory testimony of characters who’ve known Sprott both casually and intimately. The result is puzzling. How do we reconcile the doddering old coot with the bilious young seminarian, or either of these with the dashing ladies’ man who fathers an illegitimate daughter? Sprott comes off as just a sketch, but his very lack of definition makes him Seth’s most believable character since the cartoonist portrayed his own frustrating inconsistencies in It’s a Good Life, If You Don’t Weaken.

The art of cartooning seems so intuitive to Seth that we might be forgiven for failing to see the study and thought he puts into it. His preoccupation is with outcasts, with obscure and slightly awry histories. Thus we have the story of explorer and television personality George Sprott, or of salesman-cum-dreamer Simon Matchcard (Clyde Fans), or even of the artist’s own father (Bannock, Beans and Black Tea). But the figure of the cartoonist himself fits this lonesome archetype perfectly. Obsessed by the idea of cartooning, Seth invents characters that also allow him to explore the story of comics, about making them, about reading them, about being frustrated with them—in short, about loving them. And it’s no longer only through his own cartooning that he analyzes the medium. In his increasingly prominent role as designer of such high-profile reprint projects as The Complete Peanuts and this spring’s The Collected Doug Wright, his idiosyncratic methods of contextualizing each cartoonist’s work make him more critic than designer, redefining the terms by which we understand classic and Canadian cartooning.

Chip Kidd was one of the first designers to impose his sensibility on the masters of the medium, to middling artistic success and great fan consternation. A book on Plastic Man creator Jack Cole, which Kidd co-designed with Art Spiegelman, ends with a twenty-page collage of images from Cole’s zanier comics, intended to replicate the artist’s state of mind before he took his own life. Kidd would rile even more cartoon nerds with his book Peanuts: The Art of Charles M. Schulz, which focused on the early and undocumented history of the beloved strip. This choice allowed him to highlight the physicality of Schulz’s work, whether clipped from yellowing newspapers or scratched on bristol board by Schulz himself.

But Kidd’s vision of Peanuts was soon to be overtaken by Seth’s. Following Schulz’s death, Seth won the approval of the cartoonist’s widow and took on the job of designing the landmark Complete Peanuts project. It was an act of reclamation: “I hope to create a package around the work that shows it in a slightly different context than it’s been presented in for years,” he said. “I don’t want the reader to think much about it at all, but when they come to it, I hope they’re led in and out of Schulz’s work in a way that puts them in the right mood to read it again as the subtle work that it is, not as the product that has been pushed for so many years by merchandising and TV specials.” His design choices are atypical of pretty much anyone else’s take on the strip. The interiors, cast in a melancholy shade of blue, isolate the kinds of objects he so loves to centre out for attention in his own work: a car here, a mailbox there, a snowman, a record player, a puddle, a tree. They are divorced from the children who otherwise populate the strip, and who themselves hover solitary on the cover, the spine, the flaps. Seth’s is a lonely, forlorn Peanuts.

Make no mistake: this is Seth’s Peanuts more than Schulz’s. One of the drawbacks of Seth’s omnivorous approach to cartooning is that his admiration for his peers often compels him to incorporate their innovations into his own practice. Not so with his work as a designer, which remains sui generis: his take on Peanuts is the one through which most future readers will understand the strip, and with which future critics will have to wrestle. It is, in other words, authoritative. And that he presents us with a version of Peanuts that looks so brazenly unfamiliar should come as no surprise when we consider how ready he is, elsewhere, to discard, tweak, or wholly invent broad swaths of cartooning history.

Seth’s fabrications have the air of truth. His creation of the town of Dominion, for example, or of whimsical, bogus national industries like Polar Cola or Northern Fried Chicken—these enter rather easily into our consciousness. But when he combines such ersatz Canadiana with his immersion in comics history, enlivening and embellishing national and artistic narratives that might strike some as lacklustre—well, we know we’re back in Palookaville. In his previous book, Wimbledon Green, he tells the story of a world-famous (Canadian) comic book collector, who finds troves of (Canadian) comics in barns outside prairie towns, or on mad chases up Ontario’s Highway 11. But the most extreme example of his conflation of “forgotten” Canadian and cartooning histories is his invention of the New Yorker cartoonist Kalo. In the seemingly autobiographical It’s a Good Life, If You Don’t Weaken, Seth searches for cartoons by and information about gag panellist Jack “Kalo” Kalloway, interviewing the man’s family and including his photo and few extant cartoons as supplements to the main story. Seth had, however, faked this evidence of the man’s life. Kalo was a fiction.

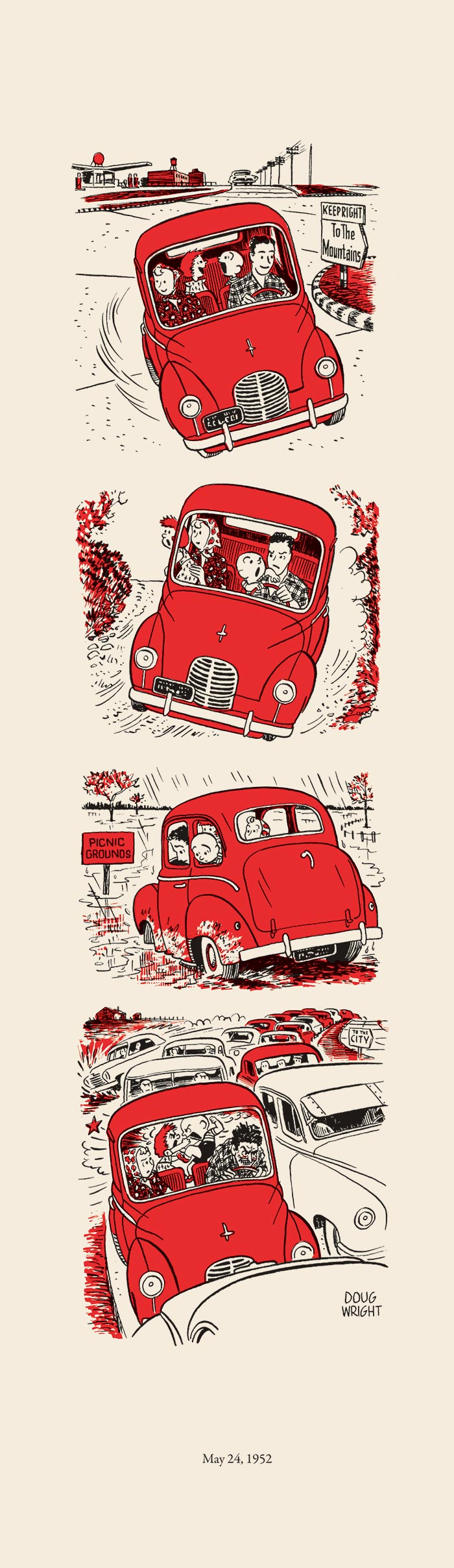

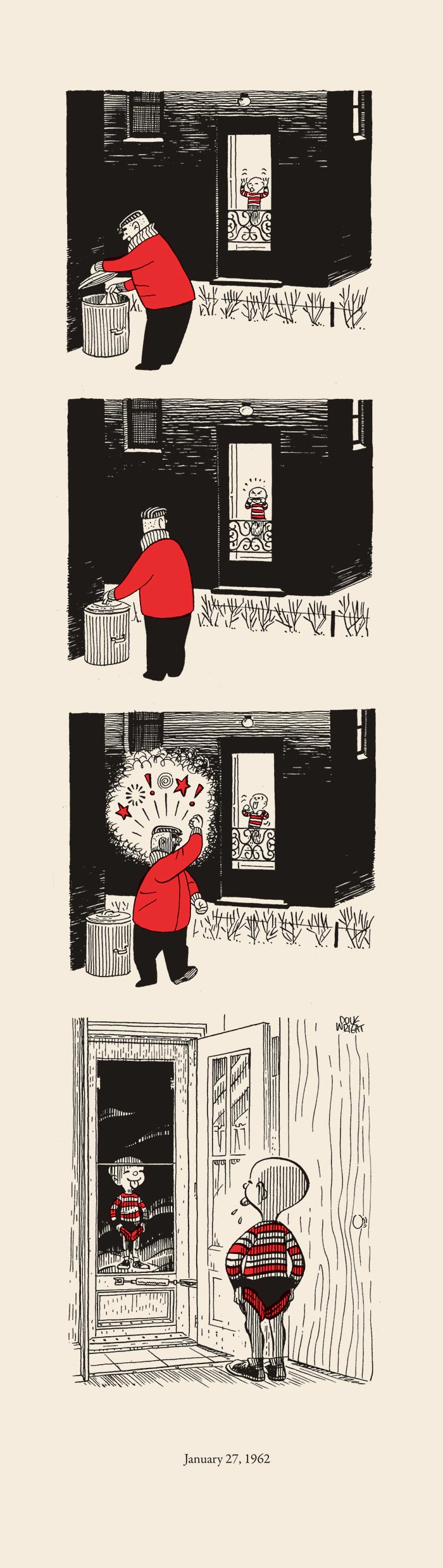

There was no need to invent Doug Wright—he actually existed. But where Seth built an entire narrative around a handful of strips by Kalo that he’d “found,” for the first volume of the new Collected Doug Wright he builds a shrine. Until recently, Wright was a neglected figure, his only legacy found in crumbling newspapers in booksellers’ back rooms. From the late ’40s through the ’70s, his weekly strip, Nipper (later renamed Doug Wright’s Family), appeared in the Montreal Standard, Weekend, and Canadian magazines. Nipper was a rowdy, young, bald-pated, striped-shirted hellion, of a kind with fellow comic brats Dennis or Calvin, but less overstated cartoon than lively regular kid, who exasperates and gladdens his parents in equal measure. In its day, the feature was highly popular, but as Seth’s co-editor, Brad Mackay, points out in his essay included in the volume, without a breakfast cereal or Saturday-morning cartoon to keep the character in the public consciousness (and a scant few long-out-of-print booklets dedicated to the work), the strip and Wright’s consummate skill have faded from memory.

No longer: Seth’s offhand advocacy of Kalo, it seems, served as a trial run for his championing of Wright. In It’s a Good Life, he mentions his pursuit of both men’s work in the same breath. In each case, he happens upon a random cartoon in some wayward shop, feels an immediate connection with it, and embarks on a search for more. Hunting out merchants who might have examples hidden away, he gradually collects a small but satisfying sample of the cartoonist’s oeuvre. After coming into contact with the artist’s family, he discovers that his subject had scrambled to the top of the cartooning heap—but the similarities end there. Kalo’s fictional output, Seth imagines, either fell out of favour or simply fell off, and the family he went on to nurture knew only the man, not the cartoonist. Doug Wright offers us a different story. While he lived, he stayed at the top, a talented workhorse, and when he died his family donated his life’s work to the National Archives. “This windfall allowed us to make this book the one that he deserved,” Seth writes.

And deserve it he does. While the book’s frequent references to Nipper as a masterpiece may come off as a tad overzealous, by any reckoning Wright was a stunning draftsman and a winning and unflinching humorist. In their prefatory notes, Mackay and Seth recite his many fine qualities. There’s his refreshing lack of sentimentality in depicting the wilful and chaotic lives of children, the stern efforts parents make to curb their kids’ behaviour, and the mercurial changes in mood one side endures from the other. Or there’s his exacting attention to technical particulars, his renderings of cars and buildings and workshops full of engaging but undistracting detail. And there’s the ease and grace with which he confronted postwar middle-class existence—suburbs and shopping, television and trick-or-treating—while making it a recognizable way of life for his readers. But he had formalist inclinations as well, developing a unique vertical layout that lends each punchline a finality not available in the traditional lengthwise format. Also among the strip’s chief accomplishments was his use of the two-colour format, the strong blacks weighting down each panel while the snappy reds guide the reader through each event and toward the gag.

Seth’s design draws upon each of these strengths in turn. As with Peanuts, he foregrounds the objects Wright draws, imparting a sense of wide-open space. But these aren’t the friendless objects or existential voids of Peanuts—rather, these things and places belong to the burgeoning Canadian suburbs in which Wright lived and set his strip, and which consisted of precisely these cars and lawns and fields and skies. The enormous skies also call attention to the unusual height of Wright’s canvas, while the overwhelming red that fills them in illustrates how sparing is his actual use of the colour in the strip. This red, too, is more vibrant, more celebratory, than the ponderous blues that lead us into Seth’s take on Schulz.

While his goal with the Peanuts books is to retrieve the strip from the quagmire of childish and mass-cult associations into which it has sunk, his approach here takes an opposite tack. With Wright, he is wresting the work from obscurity, insisting upon its importance in big, swooping gestures for all to see, stamping it out in die-cut if he has to. So we can understand how Seth would demand, at the end of his appreciation of John Stanley (the children’s comic book artist whose reprint series he’s also designing), “Go find these damn comics and save them from oblivion.” Because that’s exactly what he’s doing with Schulz and Wright, with misfits like George Sprott, and with whomever else he cares about and whatever it is he holds dear about comics, or Canada. He’s saving them all from that one-way ticket to Palookaville.