Albums and mix tapes discussed in this essay

Tha Carter III by Lil Wayne

Cash Money/Young Money/Universal Motown (2008)

So Far Gone by Drake

October’s Very Own (2009)

Thank Me Later by Drake

Cash Money/Young Money/Universal Motown (2010)

A word after a word after a word is money. For example: “I’m a Young Money millionaire, tougher than Nigerian hair. / My criteria compared to your career just isn’t fair.” That’s a bit of “A Milli,” one of six platinum- and multi-platinum-certified singles by Lil Wayne, the Louisiana rapper who coined the term “bling.” Last summer, Forbes magazine estimated his annual earnings at $18 million (US)—a recession-beating 38 percent rise over the year before. His 2008 album, Tha Carter III, has sold several million copies worldwide; its support tour, a nine-month bus ride bounded by shows in Miami, Montreal, Vancouver, and San Diego, grossed $42 million (US).

At least twice, Barack Obama has counselled children not to emulate Wayne, because it would be easier for them to slam-dunk an anvil than to walk his life path. Lil Wayne won three Grammy Awards last year, cementing his style—sex-and-drug ditties laced with raspy, digitally altered vocals—as one of the most important sounds in the global music industry.

But Lil Wayne, also known as Weezy, is temporarily leaving the rap game. By the time these sentences reach you, he’ll be a month or so into his year on Riker’s Island, the punishment for illegal gun possession. (During a 2007 search of his tour bus, nypd officers found a loaded semi-automatic in a Louis Vuitton bag.) He already looks the stereotypical part of an inmate: his beltline sags below his ass cheeks; heavy dreadlocks droop past his chest; his scores of tattoos include the words “Fear” and “God” on his eyelids. Nevertheless, it will be his first experience of jail.

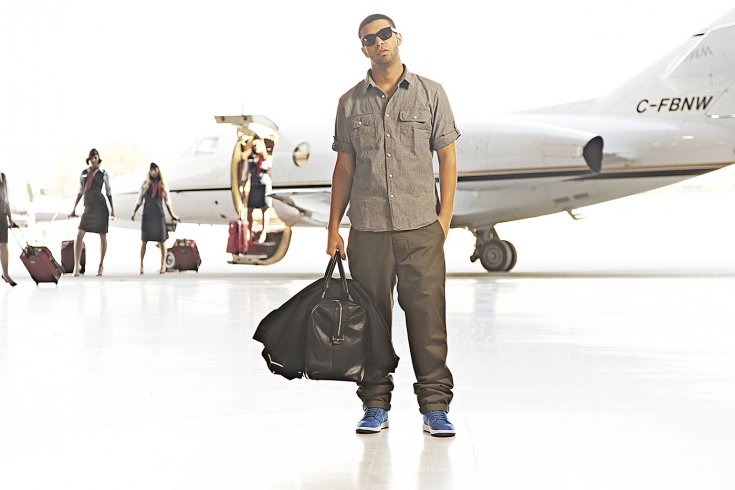

Weezy’s brand will endure his sabbatical, in large part because he has groomed a protege to take up his mantle. Lil Wayne 2.0 seems like he was designed in a laboratory, so perfectly is he suited to be pop culture’s next superstar. He was born into music, writes and raps like his mentor, dresses up instead of down, and vaguely resembles a young Obama. He is half-black and half-Jewish, media polished, and Hollywood handsome—a vocal gymnast and jet-setter who’s never known hip hop’s “thug life”; the type of gentleman a groupie would bring home to her mother. He’s also Canadian.

Before he picked up and slammed that anvil, Toronto’s Aubrey Graham was a television heartthrob. From 2001 through last year, he played basketball hero Jimmy Brooks on CTV’s Degrassi: The Next Generation. In the series, a cornball hit with young viewers above and below the forty-ninth parallel, Jimmy was shot and paralyzed from the waist down. The character became a rapper, reflecting the actor’s life. The work paid well enough for Aubrey to lease (but not purchase) a Rolls-Royce Phantom, an ultra-luxury more suited to the celebrity he had not yet become.

Aubrey had been making music using his middle name—“d-r-a-k-e, that’s me”—although nowadays he’s also known as Drizzy (a hat tip to Wayne). Four years ago, working nights after Degrassi, he recorded his first mix tape (a cassette-length playlist of unlicensed songs) with Florida’s DJ Smallz, then released it on the Internet as a free download. Drake’s support team, a trio of his friends that includes music producer Noah “40” Shebib (a fellow former child actor), sold hard copies of the tape, Room for Improvement, themselves, pushing 6,000 units based on word of mouth.

A second free tape, 2008’s Comeback Season, caught Lil Wayne’s ear. At his request, Drake went to Houston for a weekend of work and play. At some point, the MCs stepped to a microphone and jumped on a beat by Just Blaze, one of hip hop’s premier producers. Drake went first, and impressed Weezy well enough (“Count my own money, see the paper-cut fingers, / My song is your girlfriend’s wakin’-up ringer”) to spark the beginning of a beautiful business relationship. He joined Wayne’s independent empire, Cash Money Records, and soon became the standout member of Young Money, its stable of developing artists.

Last year’s So Far Gone, Drake’s third freebie, powered by smart, nimble songs like “Best I Ever Had,” “Successful,” and “The Calm,” pushed his ascent to near vertical. This giveaway strategy is standard fare for emerging MCs in Internet-era hip hop: there’s little to no cost of distribution, and copyright holders rarely chase royalties for uncleared samples. Breakout hits like So Far Gone are extraordinary, but even they basically act as loss leaders for traditional for-profit studio releases.

In the summer, there was a seven-digit bidding war, brokered by Cash Money, to secure Drake’s signature on a recording contract; Universal Motown Republic Group won, at a rumoured price of $2 million (US). Over the following months, it proved a worthwhile investment. In September, a shortened version of So Far Gone debuted at number six on the Billboard 200 chart, and has since sold close to 400,000 North American copies, despite the full tape being available online. “The Best I Ever Had,” released as his first commercial single, peaked at number two on the Billboard charts, then received a pair of Grammy nominations.

Incredibly, all this activity has preceded the release of Drake’s official debut album. Thank Me Later comes out this spring, featuring guest vocals by Jay-Z and productions from Kanye West (the Elvis Presley and Brian Wilson, respectively, of the past decade’s sales charts), and fellow Torontonians 40 and Matthew “Boi-1da” Samuels, a Jamaica-to-Toronto immigrant. With guidance from Wayne, Drake is getting famous on his own terms, in a way that could never have happened in the pre-broadband age. If his plan holds steady—so far it’s been so good—by this October, when he celebrates his twenty-fourth birthday, he will have become this country’s most successful urban music export since…well, ever.

A word after a word after a word is music. The godmother of Canadian rap is Michie Mee, a Toronto high school student when she cut her first single, 1987’s “Elements of Style,” with New York’s mighty Boogie Down Productions. The following year, she signed with First Priority records in New York, becoming the first Canadian MC to join hip hop’s big leagues. Her debut album with DJ L.A. Luv, the dance hall–flavoured Jamaican Funk: Canadian Style, was Juno Award nominated in Canada—and virtually dead on arrival at stateside retail.

“With me doing the reggae stuff, some of it was like another language [to American listeners],” Michie told me in a 2005 interview. She was dropped by First Priority but kept grinding south of the border as a live performer—usually the opening act, rarely the headliner. She turned to acting in the late ’90s, playing (what else?) a rapper on CBC-TV’s Drop the Beat.

Today, if you approach a thirty-something Canadian and shout, “This is a throwdown, a showdown, hell no, I can’t slow down!” he or she will probably advise you to let your backbone slide. Such is the legacy of Michie’s male counterpart, Maestro Fresh Wes. After striking gold here in the late ’80s and early ’90s, Wes moved south to New York—hip hop’s birthplace and ultimate proving ground. There, he was swallowed alive.

At that time, American rap was turning self-important and xenophobic. As gangsta lyrics fanned across the country like buckshot, hip hop’s dominant narrative became the individual response to harsh social conditions. Authenticity trumped artistry. Never mind that the majority of the audience lived in the suburbs: to rhyme about the ‘hood, a rapper had to come from the ‘hood. There was no space in that climate for outsiders such as the Maestro, who slouched home to Canada and, like Michie, found second life as a television actor.

There’s little else to recommend from the early years of homegrown hip hop. In 1990, an MC named Frankie Fudge rhymed a verse for Céline Dion’s club single “Unison.” Two years later, Snow became a one-hit wonder—but he was a dance hall toaster, not a rapper, and it was a guest vocalist, New York’s MC Shan, who made “Informer” a hip hop song. Tom Green, the shock comic/performance artist, was one-third of Organized Rhyme, an all-white group that presented as a pale imitation of the Beastie Boys. The Dream Warriors were more jazzy, less able than A Tribe Called Quest.

Starting near the turn of the century, a new generation of MCs, led by Toronto’s Kardinal Offishall, gave Canadian hip hop a dose of street credibility. Offishall, a baritone who wears his Jamaican heritage like a badge on his chest, is astonishingly talented, and the only Canadian rapper who can rival Drake’s resumé of superstar collaborations. He is respected in America but world famous only inside Canada. He can be grouped with K’naan and K-os, two more Toronto-area standouts, as charter members of hip hop’s middle class, which the industry no longer supports.

With physical music sales in a prolonged fall, and mergers and attrition reducing the quantity and quality of legacy record labels, a blockbuster mentality has set in: every executive is looking for the next Tha Carter III and has limited use for anything less. Hip hop has no pension plan, so young MCs must compete with a glut of aging stars for prime release dates (Thank Me Later, like Tha Carter III, has been bumped several times); stacks of albums come and go with bare-bones marketing plans. This culture of risk aversion continues to diminish foreign entry to the coveted American mainstream. Kardinal, K’naan, and K-os have not directly suffered because Michie and the Maestro failed to become stateside superstars—but the absence of Canadian successes certainly hasn’t helped them.

Meanwhile, desktop production and Internet distribution have opened a new back door to the mainstage. Lil Wayne is notorious for having made and benefited from a raft of mix tapes; Kanye West was typecast as a (very good) producer until he started rapping on them; 50 Cent owes his fortune to 2000’s Power of the Dollar, a widely bootlegged tape that caught the ears of Eminem, who then guided 50’s development as Lil Wayne is doing for Drake.

Today’s hip hop is unlike yesterday’s. In recent times, the genre has backed away from being hard. Aspiration has supplanted aggression; what matters now is unlimited access to the easy life, and songs that celebrate outsized privilege (see: Jay-Z, post-2000).

“There are people who rap about life, then there are people who rap about a life,” Drake told Vibe last December, when the magazine put him on a split run of its cover (wearing a Toronto Blue Jays cap and multi-denominational religious pendants). He raps about both, because the life he’s living has so closely come to resemble a fantasy—the fulfillment of Room for Improvement’s prophecies. He has been romantically linked to a murderess’s row of R&B divas, thrown parties with NBA icon LeBron James, and acquired a Range Rover to complement his Phantom (“Pull up, Range Rove; ‘Yo, chick—wanna roll? ’ / And I play myself in the stereo”).

Drake has a talent for clever wordplay (“Burn bread every day, boy/No toaster”*) that belies his lack of education; he quit school after the tenth grade to focus on Degrassi. His lyrics are dotted with Yiddish, and references to smoking weed, which he calls “goodie,” but he’s never rapped about slinging drugs or bearing arms. Those experiences have not touched him. On So Far Gone, his most introspective project to date, he exposed the pain he knows: life as a child of divorce.

Drake’s mother, Sandi, is white and Jewish; his father, Dennis, is black and Catholic. Aubrey, an only child, was five years old when his parents parted company. Sandi, an educator, raised their son in Forest Hill, one of Toronto’s wealthiest neighbourhoods. Dennis, a drummer who formerly backed Jerry Lee Lewis, moved home to his native Tennessee. Young Aubrey ate latkes and celebrated Hanukkah. He did not attend Hebrew school but was bar mitzvahed. In 2006, he complained to the Toronto Star about never having a high school sweetheart, because it was “too risky” for girls at Forest Hill Collegiate to court someone with his skin tone. He spent most summers with his father in Memphis, where his play was less structured than it was in Toronto (for one thing, he was allowed the occasional beer).

Music runs through both sides of Drake’s family. He has described his Jewish relatives as skilled pianists. His father’s brother, bassist and producer Larry Graham, was a key member of Sly and the Family Stone, and is credited with inventing the slap-bass playing style. Another uncle, guitarist and song-writer Mabon “Teenie” Hodges, helped Al Green compose “Love and Happiness,” “Take Me to the River,” and other soul gems. Drake, who early on fell hard for what’s become known as hip hop’s Dirty South sound—slow, lustful rap about getting high and getting off—has told a sensational story about how he began rapping: First, Dennis got himself locked up when his son was sixteen. During jailhouse phone calls, he would pass the handset to an inmate who encouraged Aubrey to trade rhymes with him through the receiver.

Some of these facts are available from Drake’s thickening archive of press clippings. Others are heard in the lyrics of So Far Gone. During “The Calm,” he details a visit to Western Union to send money to his struggling father (“So I’m fillin’ out the form at the counter once again. / He say he love me, I just hope he doesn’t say that shit in vain”). In “Say What’s Real,” he raps about his mom’s discomfort with his flashy spending; she’s embarrassed by his Rolls, so he parks five houses down and walks to her door.

Such confessions are not the standard blueprint for impressing hip hop listeners, but Drake is going after a different audience: the broader crossover crowd that can make the difference between six- and seven-digit sales. Tha Carter III made Weezy a household name, but his bizarre boasts (“We are not the same, / I am a Martian”) and extreme appearance diminish his mainstream appeal. Something similar is true of Kanye West, hip hop’s ego monster (who has insulted everyone from George W. Bush to country ingenue Taylor Swift) and the other massively successful rapper who sounds a lot like Drake. Similar to West’s platinum-certified 808s & Heartbreak, Thank Me Later will reportedly include more singing than rapping, and, as Top 40 charts have proven time and again, sentimentality plays well in the middle of the road.

A word after a word after a word is magic. What makes Drake different from Kardinal (who contributed guest lyrics to Comeback Season), K’naan (who spent time in a studio with Drake this winter), or other worthy Canadian MCs? The distinction is unrelated to rapping ability: Drake doesn’t freestyle and, if they weren’t so friendly, would be ruined in a head-to-head battle with Kardinal. Instead, it’s about everything else: impressing Lil Wayne, looking the part of a star, having the swagger to roll in a Phantom before it was prudent. Drake’s imminent success does not guarantee that others will follow to international fame and fortune, but he is kicking open a door that had once only been showing light around its edges. Put another way, he is poised to do for Canadian hip hop what Eminem did for white rappers.

The closing slot at the Grammys, ceded to a rookie performer—a foreigner, even—is a coronation. At this winter’s ceremony, Drake climbed onstage to a suddenly screaming crowd, then found his mark between Wayne and Eminem. When the spotlight hit him, standing tall in a jacket the colour of dark chocolate butter, Drizzy dipped into his part of “Forever,” a collaborative single by the three MCs (plus an absent West) that was one of last year’s most celebrated rap anthems.

Labels want my name beside the X like Malcolm,

Everybody got a deal, I did it without one.

I swear I’m about my business,

Killing all these rappers, you would swear I had a hit list.

Everybody who doubted me is asking for forgiveness,

If you ain’t been a part of it, at least you got to witness.

Any minute now.

The printed version of this story quotes a Lil Wayne lyric from a Drake song. The Walrus regrets the error.

This appeared in the May 2010 issue.