Jane salutes you from an age where to be an aficionado is to find yourself foolishly situated in the world. Where to care a great deal about something, no matter how implicitly interesting it may be, is to come across as a kind of freak. It’s interest—inordinate interest—in something seemingly arbitrary, having little to do with you or the context you inhabit. Beanie Babies, say, or Glenn Gould. Jane once met a person who insisted he was “crazy about Glenn Gould,” who owned all these rare and exotic recordings. Called himself a glennerd, happily, smugly. Did other Gould fanatics call themselves glennerds? Jane wanted to know. The glennerd shrugged, didn’t care. It wasn’t about other glennerds, Jane saw, it was only about this particular glennerd, him and his fascination. This person was not a musician. Didn’t listen to classical music as a rule.

It’s that people get fixated. People take a notion in their head. Jane, not her real name because all this embarrasses her somewhat, once had a thing for a cartoon called Robo-friendz. She was too old for Robo-friendz—sixteen, she was supposed have things for men with tawny chests, bulging crotches and leonine hair—but no, only the Robo-friendz, for about a year or so, sent her into a daily couch-catatonia. No one in her family was allowed to talk to her when Robo-friendz was on. She probably drooled as she watched, as slackly comforted—comfortably absented—as a baby nuzzling breasts.

These are the obsessions that turn your brain somehow on and off at once. They come regularly, each more arbitrary than the next. Once it was mushrooms, especially the kind that look like tiny, mounted brains. Once it was an all-male medieval choir from Norway. Once it was a website with a dancing hamster who sang a different show tune every week. She checked it faithfully each Monday morning, like a prayer to greet the dawn.

It is not like alcoholism, it is not like addiction. But it’s wrapped up with that—the pathetic psychology of it. The everlasting need to flee whatever there is to be fled from. Fortunately, one does not need to dwell on this knowledge, one is discouraged from beating oneself up in Jane’s circles. That’s good to know—you’re permitted to comprehend and yet ignore such things—that’s nice, that helps.

It started before the dream. A woman walks into a bar. Starts like a joke, you see.

A woman walks into a bar. It’s Toronto, she’s there on business. Bidness, she likes to call it, she says to her friends. Makes it sound raunchy, which it is not. It’s meetings, mostly with other women of her own age or else men about twenty years older. Sumptuous lunches in blandly posh restaurants. There is only one thing duller than upscale Toronto dining, and that’s upscale Toronto dining with women of Jane’s own age, class and education. They and Jane wear black, don’t go in for a lot of jewelry, are elegant, serious. The men are more interesting. The men were once young Turks of publishing—they remember the seventies, when magazines were run by young men exactly like themselves—smokers, drinkers—and they didn’t find each other dull in the least. Some of them had been in rock and roll bands. They wear their hair a little shaggy around the ears, now, a silvery homage. Some of them have even managed to remain drunks. This is something a lady discovers quickly over lunch: which of these silver foxes are recovered, and which are still sloshing around down there in the dregs. Wine with lunch, Jane? Oh well, perhaps I’ll join you. Half litre? Heck, why not a full one, how often do you get into town? Martini to round out dessert? Specialty coffee? At this point, both sets of eyes are liquid, glinting friendly light at one another.

If it doesn’t happen at lunch, she’ll go to a bar, later in the day, after dinner. She has a sense of decorum. She can wait until after dinner, especially when she’s on Vancouver time, three hours earlier than this gray, weighty city.

So a woman walks into a bar. Meets a man—it’s a cliché. The man is also a drunk, also an out-of-towner, also alone. After the first round, they are delighted to discover they come from precisely opposite sides of the continent. Oh, ho ho ho. Delighted in that dumb, convivial way that drinking people have. It’s not like it can be considered a coincidence, being from opposite sides of the country. But, oh, ho ho ho, they find it an inexplicable delight. To be meeting up right here in the middle.

His accent was a giveaway from the start. His quaint, alien accent, the way he can’t pronounce “th,” it’s twee, she finds it cute. You’re not supposed to find Newfoundlanders cute, they bristle at that. Some people are the same way about Newfoundlanders as others are about Beanie Babies and Glenn Gould. But his name is Ned, he’s burly, has a beard and is a fiddler. I mean, come on.

In town to play some bars with his five-part folk/trad outfit. They specialize in filthy songs, he tells her, dirty ditties. Smutty traditional tunes from days gone by, baroque with double—and sometimes single—entendres. Most people don’t want to know that cute Newfoundlanders and their Irish antecedents went around singing things like: come and tie my pecker round a tree, round a tree-o / come and tie my tool around a tree! But, says Ned, they did, and do. Ned bears himself up like a scholar as he tells her this. As the evening unspools, he sings snatches from his repertoire, and indeed most of it has to do with snatches in some way or another. The only one she is able to remember afterwards is a song that kept ending with the refrain, “ bangin’ on the ol’ tin can.”

“I never heard it called that before.”

“We are a colourful people,” Ned had agreed.

Ned wanted to go home with her—to her and not his hotel, because he was sharing his room with the accordion player. But when that idea was vetoed by the unenticed Jane—he was too burly, too bearded for her sleek tastes—he recommended they at least keep in touch. So she took his phone and email.

“If you’re ever on the rock,” he’d offered with bourboned sincerity.

The dream came after, months and months after, and had nothing to do with Ned, even if Ned was the first thing she thought of once she was able to think, that morning.

You have hangover dreams. They usually involve drinking. Not booze; water, because you’re so dehydrated it’s all your mind can think about. And on some level of sleep awareness, you know you are in tremendous pain, so you dream about relief. A cold compress administered to your head by an infinitely gentle nurse, an angel straight out of Hemingway. All white but for the roses in her cheeks. You dream of tender mercies and cool pale hands extending long drinks of water. A tumbler from the freezer—a delicate glaze of ice floating on top, frost fuzzing the sides. Wildly vivid—your mind’s so thirsty. It paints the most alluring picture it can.

That’s what Jane’s mind was engaged in this one morning. In all its desperation, it cobbled together the most beautiful dream she’s ever had.

Floating on her back in the ocean, icebergs all around. Cool, clear water, a voice was singing distantly. It sounded like Tennessee Ernie Ford. Everything blue and white—crystalline. The icebergs loomed gigantically, sheltering her. The sun was somewhere, but hidden. It was bright, but not dazzling. She wasn’t cold, floating there in the frozen ocean. She was cool.

Cool, clear water, affirmed Tennessee Ernie. Then she woke up.

She lay flat on her back for twenty minutes, gauging the pain, the depth of her dehydration. The song in her ears. She sat up and a second later, her pickled brain slid sickly back into its cradle in the centre of her cranium. Time to throw up.

Afterward, fumbling nearly an entire tray of ice cubes into a martini shaker and dumping tap water up to the brim, she went to her computer. Brought up Google Images, and spent the next three hours with them.

This was on Sunday, the day of rest. Nonetheless, she allowed herself a quick bidness email. Dean, one of the Toronto silver foxes. Reformed. Now Dean is all about yoga—having developed one of those ropey, male yoga bodies, flexible to the point of the grotesque. Nicely recovered from the seventies bacchanals, when he had run a small poetry press out of his bedroom, getting sloppy punches thrown at him by Milton Acorn, sleeping with Leonard Cohen’s braless cast-offs. Dean now oversees an in-flight magazine.

Hiya Dean, she wrote. I’m thinking of doing a travel piece.

It takes three more emails, including an elaborate two-page pitch plus one wheedling phone call to get Dean to agree to pay expenses. Her ace in the hole is the Hollywood movie, blessedly just released. Badly rendered on the whole, but beautifully shot, a veritable travelogue. Tourists are flocking as a result—flocking! she told Dean. She cribbed this from her conversation with Ned, who gave her to understand in no uncertain terms that any Newfoundlander worth his salt would wince like foot-meets-jellyfish at mention of the movie. Would bemoan the clothes (“Nobody dresses like that!”), the accents (“ like a retarded Blanche Dubois”), the incest (“always with the goddamn incest”). Plus the actors, reportedly, had put on airs. And Ned’s brother had been hired for use of his boat and the bastards had hauled stakes for LA still owing him money.

None of this makes it into the three emails and one phone call with Dean. Just the movie, and the tourists, buying up the books, sweaters, CDs, and partridgeberry jam like it’s going out of style, which of course it is.

Was it ever in style to be a lady drunk, she’d wondered, back when she was nearing her thirtieth birthday and becoming recognizable to herself. From reading, Jane determined it was not. Good for Jane, therefore, iconoclast. She calls herself Jane in a roundabout homage to her heroine, the alcoholic novelist Jean Rhys. Jane didn’t like the name, however, the pinched sound of it—Jeen Rees—like eye-slits. Jean had been a terrible alcoholic. Which is to say, she was bad at it. Jane, on the other hand, is an impeccable drunk in her driven, type-A sort of way. Jean floundered about the streets of London and Paris, roaring up at Ford Madox Ford’s window, threatening her landladies, getting arrested. Men used her and she used them in return, but never managed to derive the same blithe satisfaction from it. She let herself get beaten down, let herself get poor and old and conspicuously smashed. Flattened into jeen.

She sees from the plane. Big clumps of wedding cake floating on the deep and endless blue. Reverse sky, jagged clouds.

“Oh, look, there they are!” she says to the seatmate she has ignored for the entire jaunt from Halifax. But doesn’t turn away to see if he is looking too. Now she can see the roots of them beneath the water, extending to who-knows what depths. Of course, the bulk of these monoliths remain underwater. Hence the old “tip of the iceberg” saying. To mean: This is just the beginning. You think this is something? This is nothing.

Jane flops herself off Ned like a seal, grunting also like a seal. That’s what she feels like at such times. All torso, no limbs. A long, tapering creature, new and primordial, like something pooped out of something else.

All night since they met up at the bar it had been: Not gonna sleep with Ned, Not gonna sleep with Ned, until around one-forty-five in the morning when she decided, Ah why not. Now it is nine hours later, Ned stayed the night either because he is a gent, or because it’s a nice hotel room. She is staying at the Delta. Ned had invited her to stay at his place, had insisted, had been appalled she would turn down a stranger’s pull-out couch for a clean, well-lighted place with a sweeping view of the downtown and harbour beyond. Ned probably had that down-home hospitality beaten into him along with the holy catechism, she assumed.

He’d told her about that sort of stuff, once they were properly liquored. Catholic school. A teacher taking him aside as if for a quiet word and punching him in the stomach when he was eight.

“That’ll learn ya,” Jane had smirked, looking down.

“It did learn me,” said Ned, brown-eyed and serious above his beard.

Jane wiped the smirk off her face. “What did it learn you?” she wanted to know, being serious herself now, if not quite enough to correct her syntax.

“Fear,” answered Ned. “That’s what school’s for. To teach us to be afraid, right?”

“That’s what everything’s for.”

Oh it is horseshit that drunkards don’t have real conversations, don’t connect with others on any kind of significant level. Jane once had a boyfriend who joined AA, just to shame her, because she wouldn’t go and he thought she needed to. Then he would come home and tell her everything he’d learned at that evening’s meetings. The thing that hurt her feelings the most was when he told her there was no point having a conversation with a drunk. Nothing they said was real, he informed her, nothing they could say had any depth or meaning. They could declare their undying love for you at night and forget they had uttered a word of it in the morning.

She looks over at Ned. Perhaps there have been little-to-no beautiful moments shared between them thus far, but Ned has told her a story that rubbed at her heart, brought her to the point of Ah why not, caused her to say something she would normally be far too slick to utter, to practically yelp it, eyes bulging, turning nearby heads.

“That’s what everything’s for.”

Almost giving away the farm.

Jean Rhys was always cold in England. Thus it is with Jane, who brought precisely the wrong kind of clothes for Newfoundland. It is May, which apparently is not quite springtime around here. She neglected to pack hats or gloves or scarves. Her ears glow the moment she steps outside. It’s a good wind.

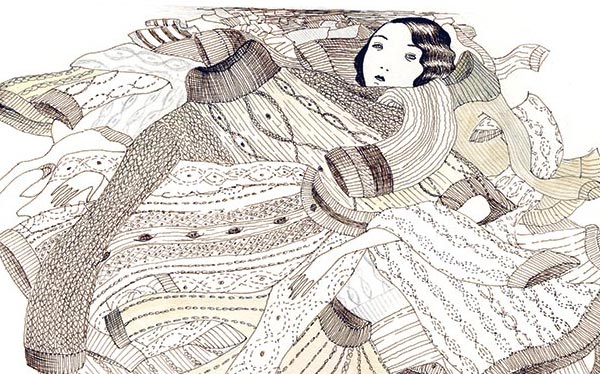

Jean Rhys used to cuddle up under blankets in her own hotel and boarding house rooms—as many blankets as she could—placing an arm over her eyes (she mentions this gesture in several stories, the supine, defeated woman on the bed, arm over the eyes). Then Jean would drift into dreams of her island home, Dominica—imagine herself growing moist and sultry from the tropical sun, not the heat of her body under thick woolen blankets. At one place, she took hot baths so often the landlady made remarks about it. Indecent implications. What kind of girl, she would ask in front of all the other boarders, took so many hot baths?

And what did Jean say? How did Jean react to this indignity? Jean said nothing. Jean went upstairs, laid down. Covered her eyes with her arm. Let the cold settle into her bones like rot.

She and Ned are hiking Signal Hill. Ned is disinclined, keeps wanting to sit on a bench and smoke. Ned is a constant surprise to her—she’d thought the beard a sort of Grizzly Adamsish indicator of his island-man’s love of the outdoors.

“Ned,” says Jane. She stretches her hamstrings on the bench while he struggles to light his cigarette in the wind. “You’ve got to take better care of yourself. It’s our responsibility as drunks to look after ourselves, make sure we eat right and get regular exercise and all that, because the bastards are just looking for any excuse to tell you how irresponsible you are, how you’re ruining your health, how you’re a drain on society. It’s up to us to throw it all back in their faces, to say, What are you talking about, look at me, I’m fine. I earn money. I pay my rent or my mortgage or whatever. I have friends, I’m successful in what I do. Who are you to judge me, and on what possible basis?”

Ned’s not saying anything. She looks over. He’s still got the cigarette between his lips, the lighter poised, his hands cupped against the wind. But he’s no longer flicking away.

“What?” she says.

“Who’re you calling a drunk?” says Ned.

“Denial,” she lectures, “is even worse. Denial gives them all the ammunition they could possibly need. Allows for feelings of superiority. Don’t give them the satisfaction, Ned.”

Ned stands, gestures at the bald rock on every side—smoke in one hand, lighter in the other. “Who’s them?” He says. “Where they all at?”

“Everyone,” she insists, flapping her hands in the wind. A particularly violent gust rocks her, for a moment, takes Ned’s smoke. He doesn’t bother to chase it.

She wishes he would go because she wants to see the bergs alone. Once she and Ned clear the bend, beyond the harbour, they stand in full view, dazzling white against two different, dazzling shades of blue. She wonders which whimsical, goofball description will work best for the article. We rounded the bend and experienced our first breathtaking view. Like massive clouds had hardened in the heavens and fallen to the sea. Awful. Jane’s mind keeps lingering on the tooth analogy—but what kind of description would that make? Like really, really big teeth.

Then she realizes why she’s having so much trouble. It’s blasphemy, what she’s doing—her deep-mind is rebelling. She has almost fooled herself, along with everyone else, into believing the article is what she’s here for. She doesn’t want to describe them, it would be wrong to describe them. She won’t do it. This is part of the self-control she was advocating to Ned only a moment ago. Who’s them, asks Ned? Them as in: Never let them see you sweat. Never let them see you drunk. Never let them know you look at icebergs.

She jogs a bit ahead on the narrow path. Ned calling, “Don’t fall!” as she disappears behind a dip of rock. Stands by herself gazing seaward for the time it takes him to catch up. “Jeez, Ned,” she says when he does, pretending to have been bored, unoccupied.

They get to the top after an hour of this. Ned has no interest in going into the tower and neither does Jane, but she supposes she has to in order to make obligatory mention of it in the article.

“Nah,” says Ned. “It’s just a gift shop and stuff about Marconi.” Jane has wandered over to the pay-telescope or whatever it’s called as Ned settles on a bench and lights his fourth smoke of the hike. She digs around in her pack for a dollar.

“Of course, you’ll get a better view from the tower,” he remarks before she can place it in the slot.

“Oh. There’s a scope up there?”

“Up the top,” he says. “You can see the gulls landing on the bergs.”

“You know what,” remembers Jane, “ I didn’t even think to buy souvenirs yet.”

“Do you need any money?” he calls as she darts away. The man is one exotic bird.

Marconi is a serene-looking man, sitting in front of his wire-thing—it really is just a bundle of wires, wires for a so-called “wireless” transmission. He’s in a desolate room, but a dapper hat and suit, dressed for the occasion, to change the world. Head turned slightly to glance at the camera as if to say, Oh this? No big deal. She tries to read about him and his world-changing wire-thing. Marconi, she notes, was an “amateur” in the burgeoning world of radio communication at the turn of the last century. Of course. He was like Jane, like the glennerd, an aficionado, only with more commitment, consistency and breadth of vision. Marconi wouldn’t have wasted his time on Robo-friendz. But Jane is certain he was after the same sort of thing, up here with his bundle of wire and big crazy kite in the middle of December. The single-mindedness is what’s key, the tunnel vision—precisely what’s required, and precisely what makes you seem a freak to the rest of the world. Visionaries and drinkers: obsessed with away, looking for else.

Something to guard against, though, Jane reminded herself. Classic drunkard mentality. That appalling self-absorption—relating everything back to one’s own experience, no matter how trifling one’s own experience might be. Marconi? Oh, yeah, he’s just like me. And icebergs are my thing, by the way, I’m the only one in the world who’s ever been interested in icebergs. She recalls a humiliatingly defining moment in a restaurant, visiting with a long, lost friend to whom she’d always felt a pinch inferior. She’d been so deep into her own navel the entire time that, as the friend detailed the difficulties of married life, Jane had finally glared across the table and spoke, “I guess I’m not like you. I’m not looking to settle down.” She’d said it in a strained, defensive way, as if the woman across the table had been sitting there smirking at her, lording her wifely status. But then Jane noticed her old friend’s face, registered her sadness and then her astonishment, followed by an ironic sort of wilt to the shoulders. The blood roared into Jane’s ears and cheeks as the sheer, breathless scale of her mistake sunk in.

The friend rested her face on an open hand, weary. She spoke Jane’s name as if calling from a distance. “I’m telling you my relationship is falling apart,” she said, leaning toward Jane. “We’re splitting up. It’s hard for me.”

Rhys, too, had the drinker’s megalomania. Jean thought everyone was out to get her, men in particular. Jean even spent her spare time writing elaborate fictional court transcripts, fashioning herself as the eternal defendant. But it wasn’t that men were out to get her. They just had no idea about this woman—a woman of the world, of Paris cafés and London dance-halls, a married and divorced woman, a woman who lived through two world wars and had two husbands arrested and jailed. What kind of woman emerges at the end of all this with an emotional skin like the membrane between shell and egg? How could any man be blamed for imagining otherwise? They didn’t want to hurt Jean. But who could have fathomed a creature so hurtable?

At four in the morning, a man out on the street is banging on somebody’s door. St. John’s is a shockingly quiet place at night, like the middle of the woods. Except for this man, a drunk of course, banging on somebody’s door on the street below. He exists, thinks Jane, like an avatar of her mind, a golem shaped from the muck of her obsessions. The Bad Drunk. The creature Jane will never be.

He’s yelling someone’s name, it sounds like Ray! or Jay! A long “a” sound—maybe even just hey! He’ll hammer a good ten or so hammers, machine-gun quick on Ray or Jay’s screen door before screaming out Ray or Jay’s name. No inkling that Ray or Jay may not be inclined to open his door to a raging drunk at four in the morning. Drunks—as innocent as lambs sometimes. We can’t afford it, Jane wants to holler down at him.

Now the lone car starts up on the other side of town. Someone has called the cops. She grins to herself, lying there, listening to the car meander its way through the streets. No element of surprise at work here. They might as well just call to the crooks across town—from the Tim Hortons or wherever—Yeah, we hear you; now just stay put.

He hears them too—the desperate man in the street. The door-banging stops all at once. Seconds before the cop car arrives. Feet against pavement, hurrying. Jane breathes relief for him.

Ned isn’t around. She ditched Ned this evening, for Ned became a downer. She did some work on the piece after the hike, took a shower, and they met at the bar around eight. It was Friday night and she wanted to meet people. She mentioned Ned’s band, how great it would be to see them play, maybe she could plug them in the magazine. Ned responded it wouldn’t be possible—they had recently gotten back from a tour, he said, and none of them could stand to look at each other for weeks after a tour. She later learned by “tour” Ned meant a weekend stint in Cape Breton.

But publicity, enticed Jane.

“We’re not really into that sort of thing,” replied Ned.

She waited for more but he just looked around the bar, scratching, sweat-moons in the armpits of his shirt.

Jane wanted a Guinness, stood up to get it, but Ned waved her back down, waving a waitress over simultaneously. Jane felt thwarted, her butt was sore from sitting. They were alone at their table, a cramped table for two, crowd roiling on either side of them. Where were all Ned’s friends?

“My legs are killing me,” he groused.

“What?” said Jane. “From the walk?”

“Yeah.”

She picked up one of his cigarettes and pointed at him with it.

“You should be doing that sort of thing every day, Ned.”

He smiled and looked away from her again. Jane felt bored.

“Where does all that Guinness enter into your fitness routine?” he asked after a moment.

Jane stretched. “The whole point of the routine is to be able to drink the Guinness. That’s the whole point of everything, at the end of the day. This is how we orchestrate our lives.”

“You talk about ‘everything’ a lot,” Ned said.

“Breadth of vision,” replied Jane, thinking of Marconi. “As alcoholics, we have a responsibility to see the big picture. We have to be unflinching. We can’t afford to lie to ourselves about what it is we’re engaged in exactly.”

Ned looked worried. His eyebrows, already joined, bunched up in the middle.

“I mean we’re engaged in drinking, yes, on the surface.” She leaned forward. “Over-drinking. Self-medication. But we have to be precise about why that is, don’t you think? If we’re going to withdraw from the world, we’d better have damn good reasons why—if, if you accept that’s what it is we’re doing. We’d better be able to rhyme off those reasons if called upon to do so. If people accuse us of being afraid, we can explain that fear is a perfectly reasonable response to the world in which we live. The trick is, we can’t be afraid of being afraid. We can’t cower behind locked doors with our gin bottles and our arms across our eyes, if you know what I mean.”

Jane waited for Ned to say something and stop looking worried. She added, “I think about this stuff a lot,” almost by way of apology. “I’m thinking of writing a book or doing a website or something.”

“Who would wanna read a book like that?” Ned asked in a naked sort of way.

“You know, Ned,” said Jane, stretching again. “I think I’ll get going.”

He nodded, pinched his eyebrows together some more, and stood up to walk her to the hotel. Jane waved him back down. Had to use both hands, stand there pushing air for five minutes at least.

“I thought, ” he says, “you’d like to see an iceberg.”

She sits up, adrift in the king-size bed, says nothing, then forces a yawn into the receiver just to let him know it’s kind of early to be calling. “I’ve already seen the icebergs,” she says in a voice like she’s packing, or blowing languidly on her nails. “I’ve pretty much got everything I need.”

“No but my brother can take us,” says Ned. “He’s got a boat.”

“Can take us where?” asks Jane, stiffening for some reason.

“Out to see the icebergs.”

“To? He can take us to them?”

“To,” says Ned. “Right to ’em.’ ”

“When?”

“Day after tomorrow.”

“Oh, Ned, I leave tomorrow morning.”

“I know,” says Ned. “But that’s the only day he can do it.”

“Why?” says Jane.

“Why?” Ned repeats, stymied. “I don’t know, you’ll have to ask him.”

“I can pay him,” says Jane.

“No, no, no, no,” goes Ned, all east coast hospitality again.

“No, but, like, to go today or tomorrow, if it’s a matter of money or something, I’ll just pay him.”

“It’s not that,” says Ned. “He’s just busy doing something. It has to be day after tomorrow.”

“Well shit,” says Jane.

“Can’t you get your ticket changed?”

Jane hadn’t thought of that. It would, of course, have to be on her own dime. Then there is the extra night at the Delta.

“I guess I could,” she says. “It might be pricey. I may have to take you up on that offer to sleep on your couch.”

“Good-good,” says Ned.

She packs her bags, tucks away her laptop and bids a fond farewell to the hotel room, which she leaves in a bedlam of newspapers and empty Evian bottles. She is always careful to dispose of her empties when out on the street, dropping them—wrapped up in plastic bags or newspapers—into the first garbage can she comes across on her way to get coffee. The worst the chambermaids can say of Jane is that she hasn’t caught the recycling bug.

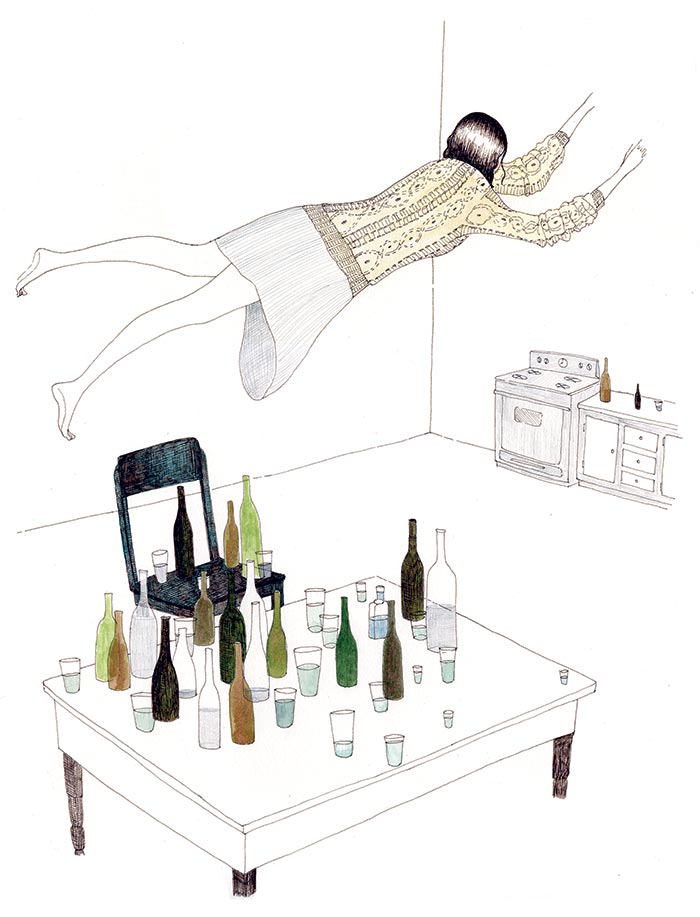

They drink three bottles of wine over dinner before Ned starts rooting around under the sink for his harder stuff. This is the nicest time they’ve had together so far—it’s because they’re not in public, they can let their hair down and drink as much and as fast as they are inclined. They sit at the kitchen table all night, pouring and talking. They are kitchen-table drunks by nature, Jane realizes—the two of them, for all their combined bar-hopping. This is what they do. This here, as Ned would say.

The drunker Jane gets, the more she remembers the dream—floating out amongst them in the cool, clear water. She’s fearless of a hangover, the dream fortifies and reassures her, tells her everything will be cool, clear sailing from here on out. Ice clinks into her glass and she touches it, imagines reaching out, wobbling to keep balance in Ned’s brother’s boat—she’s been picturing a dory, which is probably ridiculous—hand stretching toward the monolith of ice. She fishes the ice cube from her drink, cups it in her palm, holds it to her face, then eyes. Against her eyes, it starts to melt in earnest.

Jean’s problem? Jean Rhys? She expected such comfort from people, men.

Jane bursts out laughing, pops the lessened ice cube in her mouth.

“What’s that?” asks Ned as if she’s said something, smiling at her.

Jane shakes her head. She’s embarrassed, ashamed, though she’s always instructing herself never to feel this, about anything.

“The symbolism,” she laughs. “I just realized how obvious it is.”

Ned smiles and pats her hand like grandpa. It’s that stage of drunkenness where you either accept that you understand nothing, or assume that you understand everything. He heads to the cupboard for a bag of Cheetos. Jane crunches more ice, something draining out of her. She feels panic, it’s going away. She’s read that Freud treated people with recurring dreams—good and bad. He made them talk and talk about the dream until finally the patient understood precisely what was going on in his or her own head. The moment they did, the dream would depart. Freud drew back the curtain. He was like Toto, the yappy little rat who took the magic out of Oz.

Ned turns, sees her face. “No!” he says, putting the Cheetos aside. He goes to her, stands her up. “No!” he says again, her head between his big musician’s hands.

They’ll set off after lunch. Meanwhile, he’s said she will need clothes even warmer than what she wished she had put on for Signal Hill. The wind off the water and all that. Fortunately, they won’t have to putt-putt too far out into the open ocean, as the twins are situated just at the lip of the narrows. Still, Ned said, it will be “cold enough.” And no doubt the wind will be good.

She rises early, Ned still asleep in his room. She insisted on the couch after the head-in-hands thing. Her mood is bereft. The day is blinding. She needs fresh air, cleansing wind. Coffee. Not to be in Ned’s house, ashtrays on every surface.

More than anything, she wants to feel good, anticipatory. Today’s the day we go and see the icebergs.

The only place she knows to go for clothes is downtown, but the only stores she can find are meant for suckers from away, like her. One of the stores has a poster of the movie in its window, claims to have been the “outfitter.” Nobody dresses like that, she remembers, and she thinks about Ned in his brown Doc Martens, the locals in their Gore-Tex. She’s even passed a few Goths on Duckworth Street. Still, some of the sweaters are gorgeous. One-hundred percent virgin wool, and upwards of two hundred dollars. She wants one. She treats herself. This is to go and see the icebergs in.

The young cashier rings it up. Jane can see holes in her face from which jewelry has been removed.

“You’re the lady from the magazine,” the hole-faced girl accuses, folding the massive sweater into an ungainly woolen lump.

Jane stares at her. “Yes.”

“Dad was saying you’re looking to go out on the boat.”

“Dad?” says Jane, jaw-to-floor. “Ned?”

The kid laughs. “Oh god help us, no. Ned’s my uncle.”

“Oh!” says Jane, and they laugh together at the misunderstanding, though Jane doesn’t know why.

“We hoped you would come out to supper,” remarks the girl. She’s sixteen at the most with an easy, middle-aged way to her, leaning on the counter like a seen-it-all waitress with varicose veins—for whom talking to strangers has long ago lost its sense of adventure.

“I’d be happy to come to supper,” says Jane. Native hospitality at last, and just in time to save the article.

The kid frowns a stagey sort of frown, poking out her lower lip. “Well Ned said you couldn’t. He said you were busy.”

Jane blinks. “I’m the farthest thing from busy.”

“Oh,” says the kid, sounding almost disappointed. “We were all set to give you shit. Say you want a last-minute boat ride and won’t even come to supper.”

“But I want to come to supper,” Jane insists.

“When? I’ll call mum.”

“Well how about after the boat ride? I know your Dad is busy these next couple of days, so whenever is good for him.”

The kid straightens her back, turns from middle-aged waitress into impudent youngster with a twist of her mouth. “Dad’s not busy,” she scoffs. “It’s off-season.”

“Oh.” Jane pauses, the hangover-brain grinding to life. “What business is your father in?”

The kid gapes. Leans forward a little with her body. Enunciates word for word.

“He gives people rides. In his boat.”

She drifts into the street, wanting sunglasses to fend off the bright of the sidewalk. Meanders to the end of the block and turns down toward Water Street as per the girl—Raylene’s—instructions. The sign is big, hand-painted. An obtrusive sandwich-sign, meant to impede pedestrian traffic. “Dave’s Charters.” Inside is Dave, sitting behind his counter, cap pushed back on his head, and idly surfing the Internet. Raylene’s father. Brother of Ned. As tall as Ned is burly, but with the same bunching eyebrows.

He jumps up at the sound of the door —someone has stationed a too-large set of wind-chimes above it. They jangle around like the sound of madness. “Hi,” Jane shouts above the chimes.

“Ah,” says Dave. “It’s she-who-wouldn’t-come-to-supper.” He stands, smiles. All Ned’s family behave as if they’ve known her forever, and furthermore hardly approve.

“I understand you’re very busy,” apo-logizes Jane.

Dave squints, frowning the same puckered, stagey frown with which his daughter favoured her moments ago. “My dear,” says Dave. “I’m busy going broke.”

Dave has several photographs for sale. Shots of the tower, the batteries that dot the hill—guns toward the water—the icebergs, reprints of the old Marconi photos. Quality reproductions in deliberately rough, wooden frames. Overpriced. Jane pretends to study them, giving the hangover-mind time to catch up, for the gears to click more firmly into place. Eventually buying three by way of apology. To make up for cancellation of the boat ride, but also the fact that she—just remembered!—can’t make dinner this evening after all. She’s got a flight to catch.

Also she must make up for the fact that she was, apparently, staying directly across the street from Dave and family the whole time she was here. Dave with the long-“a” sound in his name, across the street from her hotel.

Because to hell with this, Ned. I will not do this thing with you.

Yet kept insisting she’d have no time for a visit. No time for anyone but Ned. Then all of a sudden demanding a ride in the boat! This, she’s gathered from Dave’s gruffness, is not how things are done. She selects a fourth print to take home, apologizing numbly all the while. It’s cutting little salt with Dave. He’ll be on the phone the moment she jangles her way out the door. Alerting local media. West Coasters Big for Britches, As Suspected All Along.

The prints of Marconi are the same images she saw at the tower for the most part. Different vantages of the same scenario; the photographer must have circled him, hoisting his heavy tripod around, ducking his head beneath a black shroud. The serene fanatic seated in his desolate, wind-blasted room at the top of the hill, wire-mess of his obsession on the table in front of him. A scribble of potential—connection unconnected.

Oh this? This is nothing.