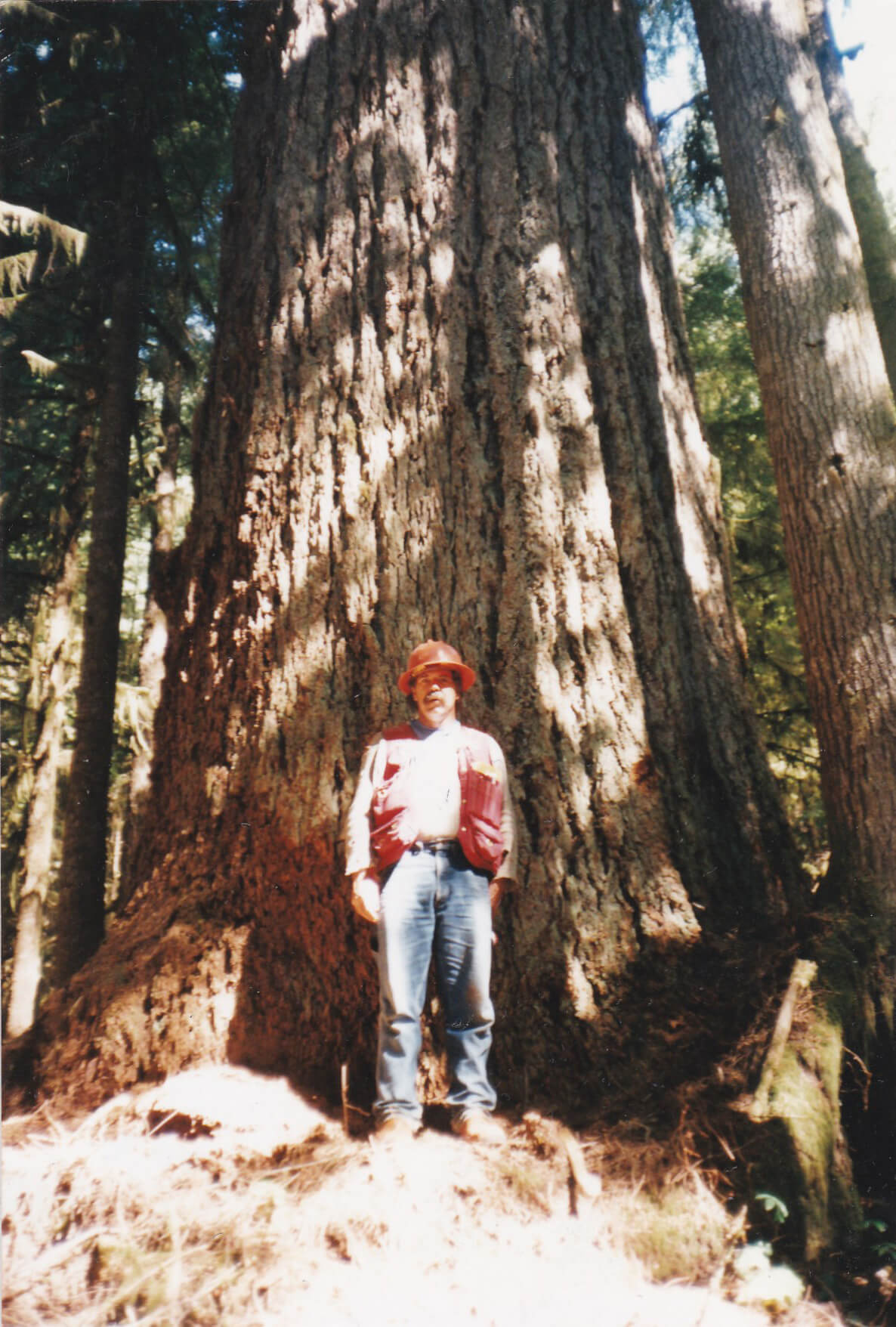

On a sunny morning in the winter of 2011, Dennis Cronin parked his truck by the side of a dirt logging road, laced up his spike-soled cork boots, put on his red cargo vest and orange hard hat, and stepped into the trees. He had a job to do: walk one of the few remaining stands of old-growth forest on Vancouver Island and flag it for clear-cutting. Known as cutblock number 7190, the twelve hectares fringing the north bank of the Gordon River near Port Renfrew, British Columbia, held some of the largest and oldest trees in the country.

Order Big Lonely Doug from The Walrus Books today!

Order Big Lonely Doug from The Walrus Books today!

Cronin began his survey at the low side of the cutblock. Every twenty-five metres, he reached into his vest pocket for a roll of neon-orange plastic ribbon and tore off a strip. The colour had to be bright to catch the eye of the fallers who would follow. He tied the inch-wide sashes around small trees or low-hanging branches. “Falling Boundary” was printed on each ribbon.

Then he surveyed the pitches and gradients of the land to plot where a road could be ploughed that would allow for the easiest extraction of logs. Walking in a straight line, he tore strips off another roll of ribbon, this one hot pink and marked with the words “Road Location.” Any creek he came across, he flagged in red. When he was done, the green-and-brown grove was lit up with flashes of colour.

While it could take 500 years for a fir to reach fifty metres tall and two metres wide, it can take a skilled faller with a chainsaw five minutes to bring it down.

As he waded through the thigh-high undergrowth, something caught his attention: a Douglas fir, poking up through the forest’s canopy and with a trunk wider than his truck. It was one of the tallest trees he had ever come across in his four decades in the logging industry—nearly the height of a twenty-storey building.

He didn’t know it then, but Cronin was standing under the second-largest Douglas fir in the country—later confirmed to be sixty-six metres tall, nearly four metres wide, and almost twelve metres in circumference. The tree’s deeply crevassed trunk was limbless until well above the forest canopy, and its grain looked straight, too: a wonderful specimen of timber. Encased within the foot-thick corky bark was enough wood to fill four logging trucks or to frame five 2,000-square-foot houses. As it could also be turned into higher-priced beams and posts for houses in Victoria and Vancouver, or shipped across the Pacific Ocean to Japan, this single tree would fetch tens of thousands of dollars.

Various large trees dominate these rainforests—western red cedars, Sitka spruces, western hemlocks—but the Douglas fir is the real icon of BC. It was prized by the settlers who built along the coast throughout the nineteenth century. In his 1918 book, Steep Trails, Scottish-American naturalist John Muir praised the species as “tough and durable and admirably adapted in every way for shipbuilding, piles, and heavy timbers.” Loggers and millers found the wood dimensionally stable—it doesn’t twist or warp when drying—while consumers prized its pronounced grain and warm colour, which made it ideal for flooring, doors, windows, and beams. Today, the species produces more timber than any other tree in North America.

Cronin reached into his vest pocket for a ribbon he rarely used, tore off a strip, and tied it to a thin root protruding from the base of the trunk. The tape wasn’t pink or orange but green, and along its length were the words “Leave Tree.”

Within a year, cutblock 7190 would be gone. Every wiry cedar, every droopy-topped hemlock, every great fir cut down and hauled away—all except one. Today, Cronin’s towering fir is one of the last of a threatened species in coastal BC, where 99 percent of the old-growth Douglas firs have been logged.

Less than a year after retiring, Cronin died of cancer, on April 12, 2016, in his home in Lake Cowichan, an hour’s drive from cutblock 7190. His career was dedicated to levelling forests, and yet by saving this one tree, he created a symbol that is doing more to raise awareness about the cutting of old growth on Vancouver Island than any protest, march, or barricade.

The words “old growth” suggest a Tolkienesque grove where every tree is a behemoth. But in reality, each stage of life is represented, from seedling to skyscraper. These forests are not simply original; they are complete.

The patches of old-growth Pacific temperate rainforest on Vancouver Island were once part of a thick band that fringed the continent from Alaska to northern California. Under the dark-green foliage, thick salal bushes make one section impenetrable to pedestrians; another opens into a clearing. Some trees appear painted in lime-green moss, while others drip with grey lichen. The larger trees pierce the canopy, allowing long beams of light to penetrate.

On the ground, a blown-down cedar can lie nearly intact for a century, slowly decomposing and becoming a “nurse log” in which opportunistic seedlings can take root. Any tree that falls, anything that dies, remains. Every hectare contains more biomass—the total volume of live and decaying flora and fauna—than any other ecosystem on the planet, greater even than the tropics, where the heat breaks down dead matter more quickly. Life teems in every square metre: insects, fungi, birds. One researcher has shown that 18,000 invertebrates can be found under a single pair of boot prints. Not only are these forests more efficient at absorbing carbon from the atmosphere than smaller second-growth trees, they also present one of the few environments in the world where large carnivores (wolves, mountain lions, and bears) and ungulates (deer and elk) exist alongside some of the biggest trees. The Douglas firs in particular play a key role, transferring nutrients from their great heights to smaller saplings below through mycorrhizal fungi that link together the roots of various species in an underground network.

It’s here, around the soggy and wind-beaten town of Port Renfrew, two hours up the coast from Victoria, that trees grow especially big. In one of the wettest places in Canada, where rain falls two out of every three days, they thrive in the flat, wet valley bottoms.

It was because of these forests that Cronin got a job as a logger forty-two years ago: he wanted to work outdoors, in nature, with sap on his hands and mud on his jeans. For more than two decades, during the heyday of modern logging, he walked the forests as a hook tender, leading a crew that hauled logs. “It was continuous clear-cut back then. You just cut everything down,” Cronin told me, shortly before he died. The introduction of mechanized feller-bunchers—capable of chopping, de-limbing, and cutting trees to length—made it possible for loggers to clear a hectare of second-growth forest in a matter of hours. But few machines are capable of felling old growth; the trees are too big. Every great tree that is cut down on Vancouver Island is done by hand. While it could take 500 years for a fir to reach fifty metres tall and two metres wide, it can take a skilled faller with a chainsaw five minutes to bring it down.

In the early 1990s, Cronin began noticing a shift in attitudes toward logging. “Everybody was trying to get dirt on you all the time,” he said. “They had cameras on you.” Two of the most successful anti-logging campaigns in Canadian history were waged over these forests. Protestors chained themselves to the base of giant Sitka spruces and camped out in the treetops in the Carmanah Valley, just north of Port Renfrew. In 1990, the province paid the largest timber company in the region, MacMillan Bloedel, $83.75 million for lost tree-farm licences and established Carmanah Walbran Provincial Park.

Three years later, farther up the coast near Tofino, the protests over proposed logging around Clayoquot Sound became known as the War in the Woods. The standoff between environmentalists and timber workers reached fever pitch when activists spent the summer blockading roads to stop fallers from reaching their cutblocks. In response, members of the logging community dumped 200 litres of excrement near the activists’ staging site. In the end, 800 protesters were arrested and convicted of defying an injunction—the largest act of civil disobedience in the country’s history. In 1995, Clayoquot Sound was protected by provincial order, and in 2000, it was designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. A year later, the Forest Practices Code of British Columbia Act (now the Forest and Range Practices Act) became law, establishing new regulations for logging companies, reforestation policies, road construction, and the treatment of wildlife habitats and watersheds.

It was during this time that Cronin became an industry engineer, a job that required him to enter intact forests and map them for logging. He was often the first one on the scene. In this role, he began seeing trees differently. “Fallers see them lying on the ground, not standing up,” he said. As big timber continued to vanish, he watched as the unbroken evergreen that once covered Vancouver Island was reduced to rare and isolated groves.

Two decades later, the battle continues. The provincial government still approves logging leases on patches of old growth in unprotected areas. And timber is still big business in BC, where one in sixteen jobs is related to the forest industry, which annually contributes $12 billion to the provincial GDP.

But while cutting down old-growth forest may be profitable in the short term, there also is an economic argument to be made for keeping these trees standing. Only 10 percent of the original forests that hold the giants remain on Vancouver Island. Given the value of old-growth as a draw for eco-tourists, long-term economic output might well be maximized if the logging industry were to focus on second-growth forest, which covers much of the island. While second-growth yields less timber per hectare, the trees are planted in a way that allows them to be harvested quickly and easily. “With second growth, there’s no waste. What you see is what you’ll get,” Cronin said.

Cutting old growth, in other words, represents a complete lack of foresight. We are on the cusp of losing the last remaining giant trees of Vancouver Island, and it won’t take a few years or a decade but many centuries to get this resource back.

For a year, Cronin’s tree swayed quietly on its own. But in early 2012, TJ Watt—who was photographing old-growth and clear-cut areas for the Ancient Forest Alliance (AFA), a Victoria-based non-profit—stumbled upon it while driving on logging roads thirty minutes north of Port Renfrew.

It was a tree unlike any Watt had photographed before. In the middle of the clear-cut, the fir stood like an obelisk in a desert. He estimated it must have been approximately 1,000 years old; it would have been a seedling around the time the Norse explorer Leif Ericson was building sod houses in what is now Newfoundland.

Two years later, after climbing the tree to measure its height, the AFA issued a press release on March 21—the International Day of Forests—titled “Canada’s Most Significant Big Tree Discovered in Decades!” The statement noted that the trunk bore a deep scar (likely the result of loggers having used it as an anchor for cables while hauling logs out of the cutblock) and that the tree’s largest branch lay on the ground nearby. The AFA suggested it had been ripped off by a storm because the tree had lost its buffer from the wind when the forest around it had been cut. The claim frustrated Cronin, who told me he’d seen the branch resting in the undergrowth the day he flagged the fir.

“Nobody would have ever seen Big Lonely Doug if we hadn’t logged that piece,” Cronin said.

This single tree provided exactly what the AFA needed: an image that could symbolize its cause. Heroic life persevering amid destruction. The organization christened him Big Lonely Doug, and the tree instantly became a celebrity. Its story rippled through the media—the Globe and Mail called it “the loneliest tree in Canada.” Numerous environmental advocacy groups used the photographs, as did the Victoria clothing company Sitka, which, as the crowds visiting the tree grew, began diverting proceeds to construct a trail and viewing platform “to keep him company.” Much of the online chatter centred on how Big Lonely Doug would be blown over by the wind. But the tree had already endured stronger weather. When Cronin walked the forest in 2011, he noticed that most of the surrounding trees were 150-year-old hemlocks that had grown back after a hurricane-force gale had torn through the valley and knocked down all trees but the greats. “He’s used to the wind,” Cronin said, “so he’s got a chance.” It’s not the first time Big Lonely Doug has stood alone.

Now tourists are visiting Port Renfrew not only to hike the famous West Coast Trail, but to head inland and stand under some of the largest trees in the world. Once a town where virtually all of the 200 residents were connected to the logging industry, Port Renfrew is rebranding itself as “Canada’s Tall Tree Capital.” In December, the town’s chamber of commerce called for a moratorium on logging old growth in the region, citing the business and tourism potential of keeping the big trees standing. The town’s tourist brochure includes a map to the area’s large trees, including Big Lonely Doug, and features a picture of the great tree on the back cover.

In late May, the BC Chamber of Commerce, which represents 36,000 businesses, passed a resolution calling on the provincial government to increase old-growth protection, stating, “the local economies stand to receive a greater net economic benefit over the foreseeable future by keeping their nearby old-growth forests standing.” They cited Big Lonely Doug as an example. Thanks to the popularity of the big trees near Port Renfrew, local hotels and B&Bs have reported a surge in demand of between 75 and 100 percent each year since 2012.

Local support, however, isn’t enough. It took years of campaigning from the AFA to establish a forty-hectare Old Growth Management Area, nicknamed Avatar Grove, in February 2012. The AFA has since constructed boardwalks through the forest to ease the impact of the thousands of visitors who are flocking to the area. But during the time the AFA worked to protect Avatar Grove, cutblock 7190 down the road was clear-cut, along with dozens of others in the Gordon River valley. “It’s so difficult to fight spot by spot,” Watt says. “In the time it takes to fight for five or six stands, you might lose hundreds.”

Hundreds more groves—such as the one adjacent to Big Lonely Doug and cutblock 7190 that contains dozens of three-metre-wide cedars and firs—remain flagged and ready to be razed, tucked away down kilometres of obscure logging roads across Vancouver Island, far from where the pavement ends. “Often the first and last people who are seeing these forests are the people who are cutting them down,” says Watt.

Throughout his career, Cronin made other discoveries while working in the forests of Vancouver Island. He once found a ten-metre-long canoe two and a half kilometres from the ocean that had been partially dug out of a felled cedar. It had been abandoned more than a century ago, he estimated, judging by the eight-inch-wide tree growing out of the log. He uncovered pre-European-contact stone tools and stacks of cedar shakes intended for longhouses. And in May 2014, while surveying a patch of forest on a mountainside near Port Renfrew, he stumbled upon the wreckage of a Second World War–era Avro Anson bomber that had mysteriously vanished while on a navigational training flight on October 30, 1942.

But of all Cronin’s discoveries, the big fir in cutblock 7190 may turn out to be his biggest legacy. During that sunny day in the winter of 2011, he unintentionally created a monument that is drawing pilgrims away from the famed coastlines and over to the front lines of the logging at the heart of Vancouver Island. “Back in the day, that tree would’ve been cut down,” Cronin said. “I’m glad it grabbed everybody’s attention. Nobody would have ever seen it if we hadn’t logged that piece.” An hour east of Port Renfrew grows the Red Creek Fir, the world’s largest Douglas fir. Nearby is the San Juan Spruce, Canada’s largest Sitka spruce. The Carmanah Giant, Canada’s tallest tree, is located two kilometres off the West Coast Trail. But these and other great trees in the area stand within intact forests and so don’t create the stark contrast that sets Big Lonely Doug apart.

Before he died, Cronin often returned to stand under the great tree he saved. He would bring his wife, Lorraine, and friends to proudly show them. “It’s a legacy, ya know? Even though I’m a logger and I’ve taken out millions of trees,” he said. Like the fir, Cronin was the last of his kind. If the remaining old growth is eventually brought down, the generations of loggers who put axe and chainsaw to trunk will have no more trees to cut, and the shift to mechanized falling will be nearly complete. When that happens, Vancouver Island’s old-growth legacy will have been permanently cut away, and with it, any potential for communities like Port Renfrew to build new economies out of groves left intact and trees left vertical.

For now, Big Lonely Doug stands tall. The tree’s thick roots, as wide as a person, draw groundwater up to its glossy needles. Below, huckleberry bushes and seedlings poke through the sun-bleached scraps where great cedar, spruce, and hemlock once thrived in seemingly inexhaustible quantities.

Each afternoon, the sun sinks toward the patchwork hills and casts a silhouette that nearly reaches the neighbouring stand of old growth—the shadow of a great sundial ticking around the clear-cut. Still tied at the base of the tree, Cronin’s green ribbon flutters in the wind.

This appeared in the October 2016 issue.

* An earlier version incorrectly identified the Avro Anson as a First World War plane.