The road to Sappar, if it can be called a road, banks off the main, rock-strewn wadi running through Jegdalek, an Afghan village tucked away in the foothills of the Hindu Kush. Under normal conditions, Jegdalek would be considered a satellite village of the capital, Kabul, which is only an eighty-kilometre drive to the southeast. But in a country ravaged by more than a quarter-century of war, it is a world apart, accessible only by truck after a punishing four-hour journey through minefields and narrow gorges. I’ve come to Jegdalek many times before. It is my translator Bashir’s hometown and for me a symbol of the vicissitudes of Afghanistan’s modern history. During the Soviet invasion, Jegdalek was a mujahedeen stronghold. My translator’s father commanded a battalion of fighters here; they ambushed the communist invaders from a web of caves and tunnels that now lie empty.

After the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, a civil war broke out between the largely Hazara and Tajik people of the north, and the Sunni-Pashtun Taliban of the south. Most of the residents of Jegdalek and its surrounding farms fled, and the area fell into the hands of the Taliban, who were ousted by a US-led coalition in November 2001. Since then, many of the villagers, including Bashir, have returned to rebuild their shattered homes and replant their desolate fields. The vales, neglected and forlorn on my first visit in the spring of 2002, are gradually turning green, carpeted now with wheat and, in some of the more secluded valleys, with the lollipop-coloured flowers of opium poppies. Life is returning to some semblance of normalcy: children are going to school, teenagers play mosa, a game not unlike horseshoes except competitors throw rocks at a target rock (closest wins). And the Kuchi have returned.

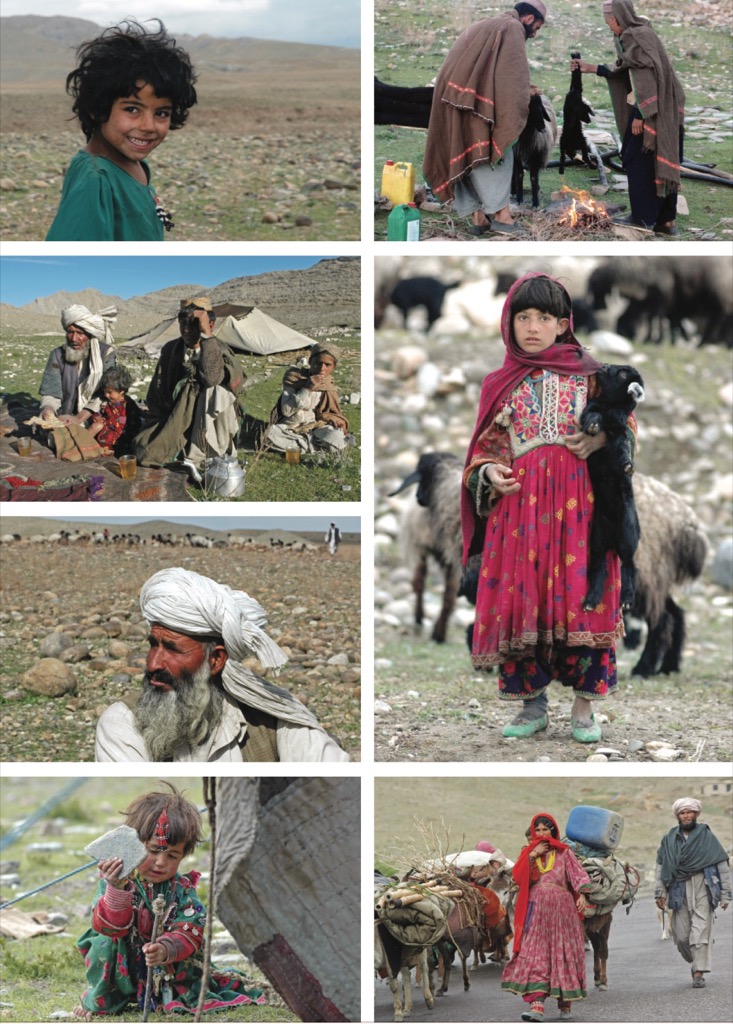

The Kuchi (which means “nomad” in the Afghan Dari language) are Sunni Muslim tribespeople who travel the alpine routes between Pakistan and Afghanistan, guiding their herds of sheep and camels to the sparse grazing grounds scattered over rugged mountain terrain. Although there are close to 2.5 million Kuchi in this country of 31 million people, they are one of the least-understood groups in Afghanistan’s often violent ethnic stew, and for centuries have occupied a unique space in the intrigues of the region. The Kuchi and their forebears have witnessed the rise and fall of conquering dynasties, including the Soviets, but have never themselves been subdued. And now Canadian and other soldiers from the US-led coalition, who have come to impose order and democracy on Afghanistan, are crossing the Kuchi’s ancient trails. While the nomads have thus far been little more than a curiosity to the soldiers, the Kuchi are capable of extreme violence. They often survive by smuggling, and when roused to it, as they were in the jihad against the Soviets, they have significantly changed the course of Afghan history. Mindful of this, the Afghan government is determined to bring the Kuchi into the country’s evolving democracy.

Spring is a traditional migration period for the Kuchi, and Jegdalek is a transit point for families making their way from Jalalabad through Sappar to the grazing grounds in the north. After a night of rain, the sky is a clear azure. The Kuchi, we know, will be on the move. As they travel, they subsist on a diet of mostly bread, yogourt, and a heavy butter sweetened with sugar. They move in family groups of four or five people, with herds of up to a hundred sheep or camels. To protect themselves against mishaps on the trail, the families stagger themselves along the route. If you wait a few hours after encountering one group, another will arrive.

Barely fifteen minutes into our drive to Sappar, we meet a family preparing for the next leg of their journey. Their camp, with its traditional earth-toned kaidi tent, is set up on a hilltop. Unfortunately, the area is littered with rocks painted bright red, lined up three years ago by the Mine Action Program for Afghanistan in order to warn people that this is a minefield. Walking to the edge of the safe zone, I call out to the heavily bearded, stone-faced patriarch. “Don’t you worry about landmines” I ask when he comes over to greet us. “Mines” he retorts, “What can we do about mines This is our life.”

The Kuchi and their animals are often maimed or killed by landmines, and every family I meet has a story to tell about someone who has lost a hand or foot, and occasionally about lives lost. Misery has long been imposed upon the Kuchi, which is one of the reasons why they are so wary of outsiders. Thankfully Laoor, the patriarch, is willing to sit with us, though he warns that he has four dogs. “You don’t want to meet my dogs,” he says ominously. He calls on one of his sons to bring out a brown felt rug decorated in orange and white flower patterns. We walk into what we believe is a safe area in the minefield and take a seat twenty metres from the tent. The women stay a safe distance away; the dogs are nowhere in sight.

Laoor is thirty years old but looks considerably older. He offers us unsweetened green tea, an Afghan staple. Lumps of candy made from brown sugar, known as gur, are placed in a small plastic dish in the centre of the rug, and Laoor’s son performs the typical Afghan cleansing ritual of pouring a small amount of tea in each glass, swirling it around and dumping it out before filling them up again. It is a peace offering of sorts, indicating that we are welcome to stay awhile. After a few cups of tea, Laoor begins to open up.

The Kuchis’ life is difficult, he says. Any shift in the political realities of Afghanistan or Pakistan can disrupt their ancient routines. For example, like the Taliban, the Kuchi are Pashtun, and when the fundamentalist regime was in power, they were allowed to take their herds into the lush Bamiyan Valley of northern Afghanistan, the same region where the Taliban blew up two ancient statues of Buddha in 2001. But the local Hazara militia has now barred Laoor and his tribe from these rich grazing grounds, which are critical to the Kuchi barter economy. Now they make do with smaller grazing areas shared with other nomads—a situation that is taxing their herds, already drastically reduced by drought. “The Taliban was better than the government we have now,” says Laoor. “The people of Bamiyan bother us too much.”

The Hazara have reason to mistrust the nomads. According to a report co-authored by Hussain Razaiat, chairman of the Afghan Multi-Ethnic Association, previous Pashtun regimes, dating back over 100 years to the reign of Amir Abdul Rahman, have offered land to the Kuchi for settlement in the Hazara-dominated regions of the north. The Hazara claim the Taliban, like the rulers before them, were using the Kuchi as a buffer between the Hazara and the majority Pashtuns. Since the fall of the Taliban, there have been outbreaks of violence between the Kuchi and the Hazara militias.

After leaving Laoor and his family to their departure preparations, we gingerly make our way out of the minefield and continue toward Sappar. The route leads off the wadi to a dirt track carved into rocky hillsides. At one point, a pickup truck filled with Afghan police officers stops. The group’s commander, who is dressed in a forest-green police uniform, happens to be Bashir’s uncle (no surprise considering my translator’s tribe controls much of the region, including the police force). “Your father called me from Kabul,” he tells Bashir. “He told me not to let you go any further. It’s too dangerous.”

Bashir’s father was the district commissioner for this area before he left to take up a government post in Kabul. The commander tells us there are pockets of Taliban and al Qaeda supporters in the area. If we are captured, he warns, they will cut off our ears and noses. But Bashir assures us that this is his home turf, that we will be safe with him. Finally, an agreement is reached: the police will drive us as far as our vehicles can go, then one of the officers will go along with us on foot. “We cannot be held responsible if anything bad happens to you,” says the commander. We agree and push on into the mountains.

My first encounter with the nomads occurred while I was embedded with Canadian troops in Kandahar in mid-March. I was accompanying them on Operation Peacemaker in the Sha Wali Kot district. The meeting was a simple case of paths crossing: we were taking a rest during a three-day foot patrol into the mountains, and a Kuchi teenager was grazing his family’s camels. When the youth passed through, Captain Kevin Schamuhn asked the translator to question him briefly. It was a surreal experience: a modern warrior and an abadi, a free person, meeting each other with equal reserves of curiosity and stoicism.

No one in the platoon had any idea how to deal with the nomads, but for the remainder of the patrol, the Kuchi were all around us—sometimes specks in the distant foothills, occasionally close enough to raise concerns that their animals would set off the trip flares acting as an early-warning system around the patrol camp. At the time, the troops were hunting for Taliban fighters in Sha Wali Kot, the gruesome incident in the region that saw one of their fellow soldiers wounded by an axe blow to the head still fresh in their minds.

“I wouldn’t recommend going there again,” says Faisal Rahman, a nomad from Bamiyan who, with his wife and three children, is making the trek by foot from Jalalabad on the Pakistan border to Logar, just south of Kabul. “There are Kuchi tribes in the area who are involved in some illegal things. Some of them support the Taliban; others just do it for the money. Either way, they are dangerous people.”

The Rahmans are relatives of Laoor, the Kuchi man we met earlier. Walking together, surrounded by lambs, donkeys, camels, and a couple of refreshingly docile dogs, Rahman is at ease and talks passionately about his love for the “free” life. “If you offered me the whole of Kabul,” he declares, “I would not take it in exchange for this life. We are free people; no one can bother us. We’ve lived through all of Afghanistan’s governments and still we are free.”

For Rahman, crossing borders unchecked is a sacred right. The only time he has ever been searched is when he attempted to go through the official crossing between Pakistan and Afghanistan at Torkham, the gateway to the storied Khyber Pass. He has never been searched in the more remote mountain passes, let alone during journeys within Afghanistan’s national boundaries.

This lack of domestic security has made smuggling a major problem inside Afghanistan’s borders. According to a nomad from the Musa Khel tribe, notorious for its involvement in smuggling, “If the Taliban need guns to be moved from one location to another, they often hire Kuchi to carry them.”

The Kuchi also transported arms during the Soviet occupation in the 1980s. “We were helping the mujahedeen by bringing them weapons and food,” says Rahman. “Sometimes we would tell them where the Russians were and where they were moving.” Another sexagenarian nomad acknowledges that Kuchi tribes captured large caches of Russian weapons, many of which are still hidden in the mountains. Many people, including some members of Afghanistan’s parliament, believe that without the Kuchi, the mujahedeen would have lost the war. “No doubt,” says Shahzadah Masood, adviser to the Minister of Borders and Tribal Affairs, whom I interviewed in his lavishly furnished office in Kabul. “The Kuchi have always been very powerful in this country.”

So powerful, in fact, that the government has bowed to many of their demands. Article fourteen of the Afghan constitution holds the state responsible for “improving the economic, social and living conditions of nomads.” And last year, the government passed legislation guaranteeing the Kuchi ten seats in the legislature. Nearly 600,000 Kuchi voted in the last election, and keeping them in the national fold is something Afghan authorities are determined to do. One plan involves settling the nomads on farms, but while there is plenty of land available, the required money has not been forthcoming. In the meantime, to survive, some have accepted humanitarian food aid, while others have stayed allied with the Taliban, with some becoming involved in the heroin trade. “Some of them smuggle for the Taliban out of allegiance,” says major General Kamal Sadaat, Director-General of Afghanistan’s counter-narcotics police force. “Others do it for money.”

For Canadian troops, the Kuchi present a particularly delicate problem. As wanderers who are technically unaligned, they are, in a sense, untouchable. But with foreign troops now patrolling the less accessible passes of the east and south in search of Taliban, clashes with the Kuchi may be inevitable. Their determination to uphold their independence in the face of foreign troops is expressed by Janat Khan and his family, who have been walking for three weeks on a dirt track southeast of Kabul. “No one can search us,” says the defiant Khan, an ageing and slightly hunched grandfather with a ragged salt-and-pepper beard. “Especially those of us who travel by foot over the mountains. We are very close. We share each other’s happiness and sadness. We help each other when we are moving.”

Most Kuchi simply shrug at the possibility of conflict with Western troops and walk on. The last Kuchi couple we meet exemplify this fatalism. It’s mid-afternoon and the sun is intense, the air choked with dust. By the time we catch up to them, Gulmeena has tied a rope around her waist and placed the other end in the hands of her husband, Shinwari, who is almost blind. She is the first Kuchi woman we’ve seen up close: penetrating grey-green eyes, hair plaited with colourful beadwork, and a vividly coloured dress.

The two have been married for sixty years, Gulmeena says, and travelling free for at least seventy-five. Neither can remember their exact ages. Gulmeena came up with the idea of using a rope to help her husband along. “Sometimes I think I’d rather tie the rope to my dog,” she says, her eyes glinting mischievously. For five minutes, the couple talk with us, straining to pull some strands of history from their fading memories. But they quickly tire of the exercise and decide to move on. As they walk off, Shinwari stumbles along behind his wife, clutching the end of his rope. This is nomadic life—binding and, above all, enduring.