The woman peers around a partially open front door. Her hair is tangled and streaked with grey. She is wearing a sweatshirt and sweatpants. We’re on Quebec Street, not far from Vancouver’s freshly gentrified Mount Pleasant neighbourhood, with its artisanal bakeries and hipster barbers. At one end of her street, construction is underway on a five-storey condo redevelopment. Four houses have been replaced with a construction pit; another four are slated to come down.

I explain that I’m a journalist. She seems reassured but keeps me on the other side of the door. The woman tells me that her father and mother have owned the two-level bungalow since 1962 and that, for more than a year, sometimes as many as two or three times a day, real estate agents have been pestering them to sell. They’ve even approached her in the alley while she was putting out the garbage. “One agent told me, ‘Don’t wait for your dad to die. You need to get out of here.’”

Offers have been as high as $1.8 million. But, if her family did cash out, where would they go? With the benchmark price for a detached house in Metro Vancouver escalating by 27 percent over the last year—hitting $1.3 million in February—and inventory shrinking because of competition from builders eager to redevelop, it would be nearly impossible to buy back into the market. Residents are coping by downsizing to condos, moving to small towns or remote suburbs, or leaving BC altogether. Sales of detached properties in Metro Vancouver reached 1,778 in February—an increase of more than one-third from the same month in 2015.

Once sold, a family house can remain empty for months. It could be empty because it was bought either as an investment or as a residence for someone from abroad with multiple homes, or perhaps because the purchaser (often an absentee buyer) is waiting to flip it for a higher price. It could also be empty because it’s part of a land assembly—a group of houses sold off for redevelopment into condos or townhouses—and awaits the bulldozer. Which is the case here on Quebec Street, where many houses have days’ worth of mail gathering on their stoops. Aside from some parked cars and this terrified woman at her door, the middle-class enclave shows few signs of life.

The woman speaks in a low monotone. I lean forward to hear her. “I’m so mad at what’s happening in my neighbourhood,” she says. “Look at me—I’m shaking.”

Farther west, some of Vancouver’s most scenic neighbourhoods, with their lush boulevards and ocean views, have been reduced to half-deserted blocks. These are the most prized houses in the city—the area’s benchmark price was $3 million in February—yet they can stay vacant for years. An effort is often made to keep houses looking lived in, especially if they’re new. Property managers or real estate agents will visit to turn on taps and pick up flyers. In the days before Halloween, uncarved pumpkins appear on front porches; Christmas wreaths hang from doors until someone thinks to remove them months later. Lights are on timers, curtains drawn. The knock-on effect has been devastating. Without foot traffic, local businesses are failing. And, with so many young families clearing out, Vancouver is mulling the closure of twenty-one schools. Frustration has even inspired a popular blog called Beautiful Empty Homes of Vancouver, which documents scores of perfectly livable but empty multimillion-dollar homes.

Jason Manning is a forty-one-year-old radio broadcaster who lives with his girlfriend and her two kids in a rented house in Dunbar, near where he grew up. The reassuring displays of domestic life that he remembers—a neighbour mowing the lawn or waving hello, screen doors slamming, children playing—have all fallen away. Manning moved in just before Halloween and immediately stocked up on candy, but only one child came to the door. In February, the city distributed new recycling bins. Many went untouched for days. “I feel like we’re in that movie The Andromeda Strain,” he says, “where everybody has died from a mystery virus, and we’re the only survivors.”

This particular disaster sequence, however, is being scripted by frenzied investor speculation, which has turned ordinary properties into blue-chip commodities. Examples of “surreal estate” pop up daily. A Kitsilano Point house sold for $1 million above asking. In Dunbar, a small nondescript house on West 22nd Avenue sold for $2.6 million and was flipped eight months later for $1 million more. In Point Grey, a ramshackle eighty-six-year-old bungalow went on the market for $2.4 million. It received three offers and finally sold for $2.5 million. Also in Point Grey, a home that was originally purchased for $4.6 million in 2011 was put back on the market in March—complete with broken windows and a disintegrating frame—for $7.2 million. “I’ve been doing this for almost twenty-five years now,” says agent Don Eilers, “and it’s nothing short of amazing.”

Many homes are eventually knocked down, sometimes with children’s toys still inside, and replaced with massive “speculation”—or “spec”—houses, some cheaply constructed, others gaudily decorative. Wary residents know the signs: first, survey stakes appear at the property corners; then, orange fencing goes up around the perimeter. On average, about three houses a day have been demolished since 2012. City hall estimates that 40 percent of all buildings will be rebuilt by 2050. And the new houses—which may end up being inhabited for only a few months out of the year—will be outside the financial reach of almost everyone who works and lives in Vancouver. A year ago, a developer named Tim Wang paid $2.6 million for a character house on the west side. Once he redevelops it as a boxy 5,000-square-foot house with tile cladding, he expects to sell it for $4.8 million. To a greater extent than those in hot spots such as Toronto, San Francisco, or New York, Vancouver’s market has utterly decoupled itself from local incomes. Between 2001 and 2014, average Vancouver salaries increased by 36 percent—according to the most recent census numbers, the median household income was $73,390—while home values skyrocketed 63 percent.

Without data, claim politicians, no one can say with certainty what has sparked the affordability crisis. In order to address complaints that vacant single-family homes are driving up prices, the city recently released a study examining electricity usage in 225,000 homes over a twelve-year period. It found that empty housing stock was concentrated in condos. However, its methodology overlooked houses that are newly built and under construction, and the study did not properly account for houses used as pied-à-terres for a few weeks out of the year or awaiting permits for demolition. Taken together, these represent many of the empty units on the west side.

Developers and industry types have always preferred to blame lack of affordability on lack of supply, which they say is due to population growth and limited geographical space. Others point to low interest rates—although Winnipeg has seen the same rates, and that city isn’t unaffordable. Downsizing boomers are also seen as driving demand as they trade their homes for condos. But, even taken together, these factors cannot explain the wildly out-of-sync price-to-income ratio—which is by far the highest in Canada. A typical detached house in a normal city traditionally has cost about three or four times the median household income. In Metro Vancouver in 2014, according to the Bank of Canada, the multiple was roughly ten.

The better question is, Who can afford all these homes? When we follow the money, it leads primarily to the city’s newest wealthy class: buyers from mainland China.

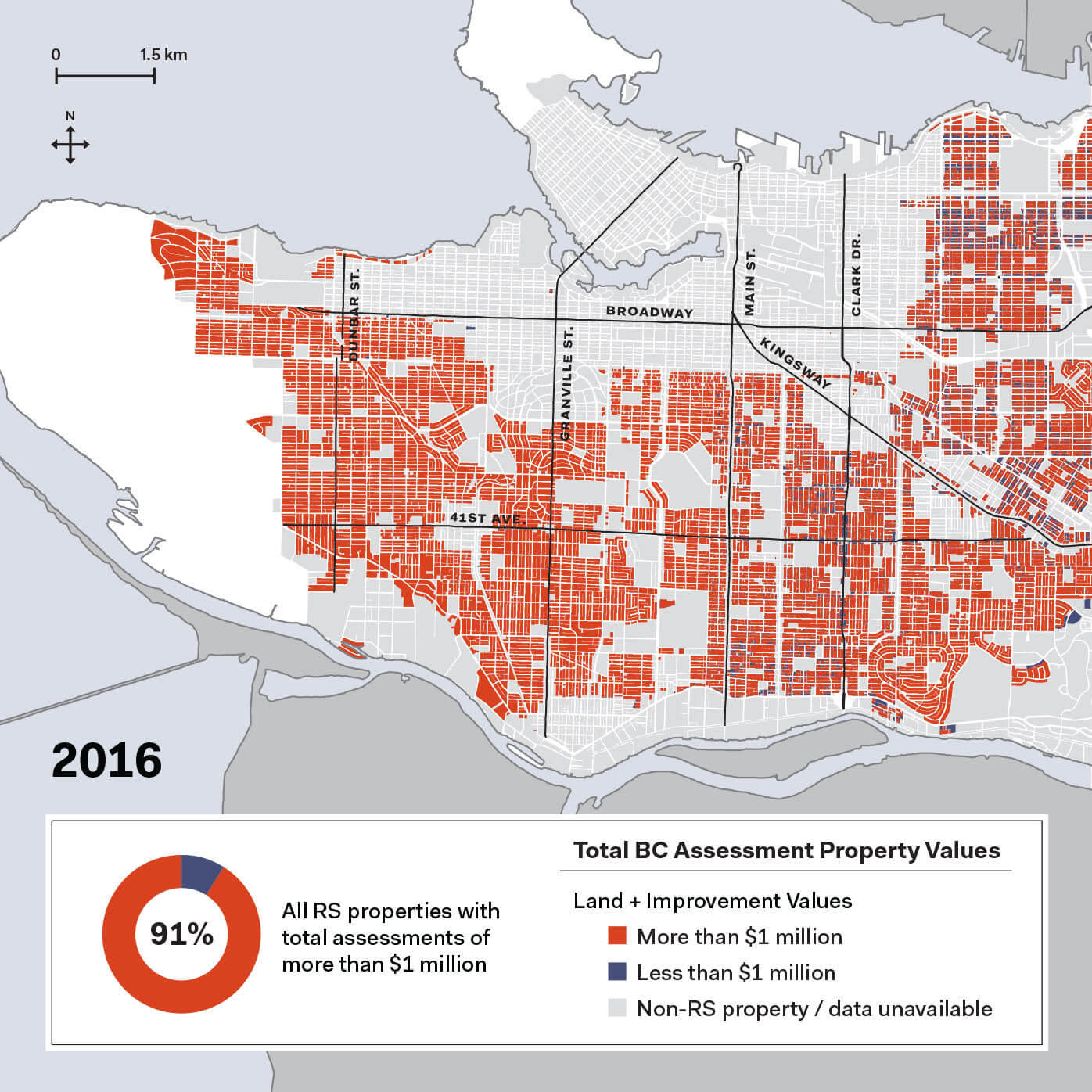

Graphic by Meredith Holigroski

Vancouver has a shameful history when it comes to visible minorities. Starting in the 1870s, Chinese labourers who arrived to work on the transcontinental railway had to pay a $50 “head tax” for the privilege of immigrating here (by 1904, the amount had grown to $500). They weren’t allowed to vote or to travel in certain areas of the city. Shaughnessy and the British Properties neighbourhoods, which were as prestigious then as they are today, had covenants on land titles that barred houses from being purchased by “any person or persons of the African or Asiatic race or of African or Asiatic descent”—a practice that reportedly did not end until 1955.

It’s no surprise that residents of European descent are uneasy even suggesting that Vancouver’s affordability crisis might be connected to the influx of China’s new money. No one wants to be accused of stereotyping or of spreading paranoia about a twenty-first-century “yellow peril.” For a long time, only agents would talk openly about the rich mainland Chinese clients snapping up their houses. Vancouver’s Macdonald Realty, which has an office in Shanghai, made local headlines when it revealed that Chinese buyers accounted for 70 percent of the firm’s sales for houses above $3 million.

But Andy Yan found data that went further. Yan is the acting director of the City Program at Simon Fraser University and works as an urban planner for local architectural firm Bing Thom Architects. As part of a study run out of the firm’s research division, called BTA Works, he estimated that, over a six-month period, Chinese buyers accounted for 66 percent of all residential land purchases in the expensive west-side communities of Dunbar, University Endowment Lands, and Point Grey. The province does not keep track of buyers’ countries of origin, so Yan went through land-titles records and identified all non-anglicized Chinese names. (Anyone with an anglicized Chinese name, such as his own, didn’t qualify, because that would suggest they’d been in Canada for some time.) The methodology wasn’t airtight, but the work had been peer-reviewed, and it held up as solid evidence that the Chinese were the dominant players at the high end of the market.

Yan released his findings to the media on a Monday last November. By the end of the week, the forty-year-old academic was fending off attacks from those who claimed his data smacked of racism. “This can’t be about race,” Mayor Gregor Robertson told CBC’s The National, “and it can’t be about dividing people.” In the same segment, development consultant Bob Ransford echoed this sentiment. “The danger,” he said, “is intolerance, racism, singling out certain groups of people, saying they’re to blame for this.”

But the issue is one of money, not race. Global money is boosting Vancouver’s prices, and local dollars can’t compete. Most troubling is that many homeowners are now selling directly to buyers in China, listing their homes in real estate exhibitions in Beijing and Shanghai. Vancouver realtors are helping them and making a fortune. Average-earning buyers are being entirely cut out of the purchasing loop. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, the Ottawa-based agency that tracks housing data, is so concerned that it has reportedly accelerated its collection of figures on foreign investment, especially in Vancouver. For years, Tsur Somerville, director of the University of British Columbia Centre for Urban Economics and Real Estate (which one writer dubbed the “academic wing” of Vancouver’s real estate industry), blamed xenophobia for concerns about offshore investing. But, in February, he abruptly acknowledged that real estate prices were inflated by “a massive change in the official currency reserves in China”—more specifically, wealthy individuals and companies moving money out of China and into Vancouver.

Vancouver isn’t an isolated example. With China’s economy slowing, the wealthy have increasingly looked elsewhere to park their cash safely. They’ve focused on gateway cities in North America, Australia, and the United Kingdom, including New York, Los Angeles, Melbourne, Sydney, and London. An unprecedented $1 trillion (US) flooded out of China last year. In 2014, $16.6 billion was invested in Canada, largely in Toronto and Vancouver. But buyers are now branching out into smaller cities as well, where they can find better deals. In BC’s north, for example, Chinese enterprises have invested heavily in resource land around proposed mines and pulp mills. Foreign investment has caused house prices to spike above the $1 million mark throughout Burnaby, Richmond, Port Moody, Coquitlam, South Surrey, Tsawwassen, Vancouver Island, and other areas in the region.

But Vancouver itself leads the pack. Demographia’s Housing Affordability Survey ranks it in the top three of the 367 least affordable housing markets in the world, along with Hong Kong and Sydney. And that tells only part of the story. The annual analysis, now in its twelfth year, includes all of the Vancouver region’s housing types—even the 290-square-foot micro-condos. The survey’s founder, Wendell Cox, says the city’s detached-house prices are on another plane. “They’re more expensive than anywhere else, by a good margin,” says Cox. “I don’t know how you get out of this situation.”

The affordability crisis doesn’t hurt just low-income earners. Tech-industry workers, even those from major companies, are fleeing two-bedroom condos for better job opportunities in Seattle and San Francisco, where the compensation is better and houses are within reach. Raza Mirza was one of a group of eight software engineers recruited from Pakistan by Microsoft’s Vancouver office. Today, he knows of only two who stayed. The remainder relocated to the US (Mirza now lives in Victoria, where he pays two-thirds the rent he paid in Vancouver). Engineer Eric Murray was once CEO of a clean-tech company in Burnaby. He lived in Raleigh, North Carolina, because he could enjoy a higher standard of living there—including a 3,500-square-foot house and private school for his kids. He would fly into Vancouver every third week for work.

Murray still lives in Raleigh but found a new job in Ontario. He continues to visit relatives in Vancouver, a place he considers too costly for a six-figure professional like him. “My aunt lives on a pretty normal street,” he says. “When I go see her, two-thirds of the lights on her street are off. No one is there.”

The issue of how the global migration of big money affects communities is being discussed all over the world. But Vancouver has shied away from the conversation. In many cases, argues Yan, “charges of racism are being used to justify the housing status quo and continue the inflow of money.” The Canadian government has not intervened—we are the only G7 country without a national housing policy. Australia and England now collect data on foreign ownership and have closed tax loopholes to help cool their high-end markets, but BC refuses to curtail the offshore buying for fear that homeowners will lose equity. “The responsibility is provincial and federal,” says Yan. “Policy is not just about the actions you take. It’s about what you don’t do.” And if we don’t do something soon, he says, the price will be paid by future generations, who won’t be able to afford to live here.

The business of buying, building, and selling houses in Vancouver is worth more to the province than its mining, natural gas, and forestry industries combined. Last year, detached-house sales throughout the region totalled $38.6 billion, and residential construction added up to $21.6 billion.

This redirection of the economy toward real estate reflects a calculated effort by government going back at least thirty years. A shrinking economy in the 1980s led Canada, and BC in particular, to start eyeing Asian investment as a fix. All three levels of government embarked on trade missions to Japan, Hong Kong, China, and Singapore. Vancouver—where, in 1981, house prices had dropped by 40 percent—worked hard to publicize the city’s fine geography and standard of living during Expo 86. The courtship paid off when Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka-shing purchased the eighty-two-hectare Expo lands as a single land holding. His interest in what was then seen as a modest seaside city inspired other wealthy buyers from Hong Kong, who were troubled by the uncertainty surrounding the handover of Hong Kong in 1997.

But this was the first stage of a larger migration from mainland China. The country’s newly rich became mobile and went in search of better lives. By 2013, more than 9 million people had emigrated from China, according to the UN International World Migration Report. In 2014, a survey by the Hurun Report—a monthly magazine best known for its annual ranking of China’s wealthiest people—suggested that 64 percent of China’s richest individuals, those with a self-declared worth of at least $7 million (US), had either emigrated or were making plans to do so. Respondents to the survey cited pollution, lack of food safety, and a poor education program as their key reasons for fleeing. Their top destinations were Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Vancouver.

In Canada, citizenship was typically expedited through the federal government’s immigrant investor program. Created under the Conservative government in 1986, the policy gave permanent-resident status to any wealthy investor who’d agree to loan Ottawa $800,000—repayable without interest after five years. Canada was effectively selling Canadian passports. The program became hugely popular because it was one of the cheapest in the world. Australia required a $1.5 million investment; New Zealand, $1.3 million; the UK, $1.4 million. The US demanded $1.3 million and the creation of ten new jobs. By 2012, it had become clear that many newcomers created so-called astronaut families, taking advantage of health care and education for their children, while continuing to spend most of their time abroad for work.

By the time the federal government shut down the program in 2012, it had a backlog of 65,000 pending applications, reportedly 70 percent of which came from China. But the Quebec immigrant investor program still provides a loophole. The old federal rules apply under the Quebec program, which accepts 1,750 applicants a year. The federal government estimates that 90 percent of those applicants head to other cities instead of settling in Quebec as required—the majority to Vancouver.

The effect on the city has been profound. In 2006, according to Andy Yan, 19 percent of single-family homes were valued at more than $1 million. Nearly a decade later, that share has jumped to 91 percent. For Yan and others, the connection between Vancouver’s escalating property prices and the arrival of offshore buyers is clear.

“Foreign investment drives the top end of the market,” says David Ley, a geography professor at the University of British Columbia who has spent sixteen years studying Asian investment in gateway cities. “Anyone who says otherwise is either misleading or misled.” Ley considers the wealth-based immigrant program a failure. Certainly, he says, few jobs ever came of it—and little tax revenue. Since the 1980s, he estimates that more than 200,000 Asian immigrants have come to Vancouver through federal-based investor programs. An internal-use-only study from 2012 conducted by Citizenship and Immigration Canada (and unearthed by South China Morning Post reporter Ian Young) showed that, after five years in Canada, only 39 percent of program applicants reported any income earnings. Those who did report annual income showed an average of $21,000 at the five-year mark. After fifteen years here, the figure climbed slightly, to $25,000. Refugees, the study showed, averaged $30,000 in earnings after fifteen years—more than people who came to Canada as “investors.”

Cameron St. John, whose work involves helping a Chinese venture capitalist buy properties in Alberta, feels the investor program has brought mixed results. St. John lived in Hong Kong and married a woman from mainland China in Australia before moving back to Vancouver, where he grew up. He says the city has “already become a retirement suburb of Beijing” but argues that houses are assets that should be open to the free market. His main concern is that the growth is not paying for itself. “That is a legitimate worry, if people are claiming Canadian services and not declaring their taxes here,” he says.

As Canadian ambassador to China during the bulk of the exodus from 2009 to 2012, David Mulroney had a special vantage point as Chinese multimillionaires arrived in BC. He worries we don’t know half of what’s going on. The Chinese government allows citizens to pull only $50,000 from the country—so how are they buying multimillion-dollar properties? “Based on my experience,” he says, “we are probably in danger of importing hot money.” By which he means illegal, or illegally transferred, funds.

There’s the telling example of former CIBC financial advisor Guiyun Ogden, who was fired from her job managing a $233 million portfolio for a wealthy Chinese client in Vancouver after it was discovered she’d used her own bank account to move some of her client’s money. As a Globe and Mail investigation revealed, the bank had long supported the practice of using multiple wire transactions to transfer big sums out of China without running afoul of the $50,000 limit. Ogden had helped her client move $500,000 (US) through friends and family, who sent ten wire transfers of $50,000 (US) into ten CIBC accounts—money used as the down payment on a $5.7 million Vancouver mansion.

The investigation suggested that other major players in the industry might be complicit as well. Since 2012, when China began its anti-corruption campaign to stop citizens from illegally funnelling funds out of the country, Vancouver financial institutions have reported 8,200 suspicious transactions to the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada, the agency that tracks money laundering. Of those transactions, 96 percent were facilitated by banks—which are required only to flag suspicious activity, not stop it.

As noted above, the BC government doesn’t place any real estate restrictions on foreign buyers, nor does it have a specific tax or fee for properties purchased by non-residents, the way authorities do in Hong Kong, London, Melbourne, and Sydney. When Mayor Robertson proposed taxing luxury properties as a way to penalize flippers, Premier Christy Clark refused, referring to a 2015 Ministry of Finance report that challenges the perception that foreign investors and speculators are driving Vancouver’s affordability crisis. “The data we have,” it states, “does not support this perception.” Clark argued that foreign buyers made less than 5 percent of purchases. The Ministry of Finance, however, got that figure from the BC Real Estate Association, which represents the very industry now enjoying extraordinary commissions (every $1 million worth of house nets agents about $30,000).

As of February, when it released its budget, the government continued to dismiss claims about the impact of foreign buyers, with finance minister Mike de Jong calling them “speculation.” Instead of cooling the market by introducing a tax on empty or flipped houses—a move made by other governments—the province offered tax breaks on new home construction to cushion the costs for homebuyers. The budget included a 3 percent increase to the property-transfer tax on luxury homes costing more than $2 million, and the reintroduction of a citizenship declaration form, on which buyers must declare whether they have Canadian citizenship or are permanent residents. But critics argue that this is the wrong question to ask, as the thousands who’ve come to Vancouver through immigrant-investor programs already have permanent-resident status.

“The whole thing is soul-crushing if you think about it,” says Paul Robinson, a thirty-four-year-old senior engineer who lives downtown in a two-bedroom condo with his girlfriend. Robinson can’t help but compare his life to that of his high-school friend in San Francisco, who earns enough from his job in the tech industry to afford a house in the city. For a Vancouver millennial, he says, the only hope is that parents sell the family home to a foreign buyer and share the wealth with their kids.

One seller, who grew up on Vancouver’s west side, told me about a day last summer when his parents put the family home on the market for $3.5 million. They had their first response within an hour. Suddenly, Mercedes-Benzes and BMWs started slowly cruising down the street, each with a middle-aged man in the passenger seat and an agent at the wheel, craning his neck. Nobody viewed the interior of the house. But, within four hours, they received five offers, including one for $4.2 million, which his parents accepted. When the paperwork came back from the notary a few hours later, it bore the name of a different buyer. Within hours, the house had already been resold. The agent couldn’t explain what had happened.

Called shadow flipping, the popular practice exploits a previously little-used clause in the selling contract whereby ownership of a property may be reassigned to a third party after the homeowner sells. By the closing date, a house might already have been flipped multiple times, sight unseen, names unseen, amounts unseen. The agent makes tens of thousands of dollars of commission with each flip. (They might also have been involved in the assignment all along and reaped even greater profits.) The seller and his parents felt as if they’d received a windfall. But, if their house ultimately sold for $5 million—not impossible in this scenario—then that’s $800,000 they missed out on. This kind of shady behaviour is typical in an overheated market. “No one is looking after the citizen,” says Ley.

In February, when news of shadow flipping sent shock waves around the Lower Mainland, the government announced that it would set up a task force to investigate. The province also said that it would study foreign buying but that the results of the inquiry might not be made public. “Since when is a census not made public?” asks David Eby, housing critic and NDP member of the legislative assembly for Point Grey. A forty-year-old lawyer who lives with his wife and baby in a tiny condo, Eby has pushed the province and the real estate industry to clean up sketchy practices and to tax speculative buying. He writes letters to government and regulators and holds press conferences to plead his case to the media. The emphasis, he says, needs to be on foreign money, not foreign buyers: undeclared, untaxed wealth earned offshore is where any investigation should start.

The unaffordability crisis brings with it other considerations. With close to 1,000 house demolitions per year, the environmental costs of the building frenzy are climbing. Each razed house sends about fifty tonnes of rubble to landfills. Before the city instituted its urban forest strategy, rampant deforestation (agents complain that properties with big trees are worth less) resulted in tree-canopy shrinkage equal to about 400 hectares—roughly the size of Stanley Park.

Already, the old west-side neighbourhoods have been rendered architecturally unrecognizable. Some streets rival the Las Vegas strip in their ersatz diversity. You might see a mountain chalet complete with river rock next to a version of a French Normandy manse.

One popular style is a large, tall box covered in marble or limestone tiles, which is nicknamed “the urinal” by locals. City heritage policy lacks the teeth to protect Vancouver’s history properly. While Victoria has more than a dozen heritage conservation areas, Vancouver has created only one, in Shaughnessy, and moves are already underway to soften the restrictions there because rich residents are suing. Homeowners, including new Chinese expats and long-time residents alike, are worried that, without the ability to demolish their homes, they’ll lose equity. The homes that spring up are, on average, 77 percent larger. Yet, notwithstanding a city hall that pushes density, they house fewer people than do the homes they replace.

City hall could cool demand by getting tough about heritage protection or by rezoning targeted neighbourhoods so that bigger houses can’t be built. But that would require political will. There are also fears the municipal government is too cozy with developers, many of whom have financially supported the city’s ruling Vision Vancouver party.

The story of a humble bicycle lane helps explain why people are suspicious of city council’s role. In 2013, the city passed changes to cut off through-traffic to eight blocks of Point Grey Road. It then turned the area over to bikes and local traffic—at a cost to the taxpayer of $6 million. On one of those blocks sits the province’s most expensive house. Valued at $63.8 million, it belongs to Lululemon founder (and major Vision party donor) Chip Wilson. At the time, Mayor Robertson lived nearby, in a $1.6 million duplex with wide-open views. Protesters, newspaper columnists, and bloggers accused the mayor of using his Vision party’s much-hyped “Greenest City 2020 Action Plan”—intended to make the city friendlier to transit, cycling, and walking—as cover for creating what amounted to a gated community for himself and other wealthy homeowners. Although he had no legal conflict of interest, Robertson recused himself from voting, and his Vision-dominated council passed the action. Non-Partisan Association councillor George Affleck was one of the few who voted against it. The city, he says, spent a total of about $18 million on that stretch of bike route. It spent another $35 million overhauling the Burrard Street Bridge crossing. “How much affordable housing would that have given us?”

Meanwhile, as buildings keep coming down and new ones keep going up, residents keep getting pushed out. Renters, who make up roughly half of Vancouver’s residents, are particularly vulnerable. The average household income for renters is half that of homeowners, at around $41,000. For some, staying within a community has become a matter of nomadic survival. Semiretired sixty-year-old Daryl Morgan has been evicted seven times in the last ten years. In almost every case, the landlords wanted to make renovations and increase the rents. He’s applied for the government’s low-income housing program, which has a five-year wait list. They told him, “You’d better be prepared to go to a shelter.” He recently moved into a suite in a house owned by a doctor and his wife, but every day he worries they’ll end up selling to one of the real estate agents knocking on the door. And then he’ll have to start looking all over again.

Entire apartment buildings have undergone “renovictions.” Such cases can be fought through arbitration, but not everyone has the time or energy—or money—for battle. Compounding the problem is that traditional forms of rental homes are disappearing. Basement suites have been a Vancouver mainstay, offering cheap rent to students, retirees, and single workers, as well as being a mortgage helper for the homeowner. But the uber-rich who have entered the housing market don’t need the revenue, so many of the new homes being constructed don’t include secondary housing. Available rental housing is being squeezed further thanks to the proliferation of empty condos—one of the first major signs of investor money a few years ago. About 23,000 Vancouver condo units are non-resident owned and under-occupied, often leased through property-management companies that run them like hotels.

Bob Rennie is a celebrity in Vancouver—the Four Seasons Hotel even christened a $23 grilled cheese sandwich after him. The chief marketer of the condo towers that dominate the region’s skyline, Rennie is one of the most powerful people in BC and a lobbyist for the real estate industry with close connections to the provincial government. He believes in being pragmatic about the acceleration of change. “I’ve been at this for forty years, and when I see the in-migration, it’s scary. I don’t want my city turned into a resort. But we have to be realists and understand where we are going.” Where we are going, he says, is away from the urban core and toward long-distance commutes.

Not surprisingly, Rennie sees the creation of more multi-family housing throughout the region as the only realistic avenue for building affordable housing. He admits, though, that the very idea of “affordable” will need to adapt—downtown condos will never be less than $1,100 a square foot again. But he’s dead set against taxing foreign money. Earlier this year, a group of economics professors from UBC and Simon Fraser University proposed that the province create a BC housing-affordability fund. Under the fund, owners of vacant homes, or homeowners who live abroad and contribute very little to the Canadian economy, would face an annual 1.5 percent surcharge on their properties. A vacant $10 million house, for example, would be hit with a $150,000 surcharge. The proceeds would be shared, through lump-sum payments, with residents in the same area.

Taxing foreign buyers, warns Rennie, would cool the market to such a degree that locals would lose their retirement equity. He estimates that Vancouver’s boomer parents and grandparents have about $200 billion in equity, and a good chunk of that will go toward the purchase of homes for their children and grandchildren. He’s seen that transfer of equity first-hand through the condo projects he’s marketed. Roughly half of the 540 first-time buyers he dealt with last year received financial help from parents or grandparents.

But is it reasonable to expect an entire generation to depend on handouts to buy houses? More than 300,000 people in Vancouver are twenty- to thirty-year-olds. Not everyone in that group can count on a home-equity inheritance. Some have parents who are too young to sell, and some have parents who will need that money for retirement.

Eveline Xia, who currently rents, was raised in Burnaby, California, and France before moving to Vancouver, where she got a master’s degree in environmental studies. Angry at the lack of affordable housing options for her generation, the thirty-year-old started the hashtag #donthave1million last March; it went viral, drawing hundreds of frustrated tweets from financially struggling millennials—medical-software analysts, lab technicians, film editors—who worry constantly about being priced out of Vancouver. “This kind of global wealth isn’t going to end,” says Xia, referring to the inflated market. “It will get worse.”

Rennie doesn’t have much patience for this kind of affordability angst. Young professionals, he insists, must be prepared to give up on the idea of living in the city. Instead, he believes they need to open their minds to moving to suburban areas like Burnaby and Coquitlam, which is why he’s pushing for more residential building around transit hubs such as SkyTrain stations.

And what of millennials who complain about commuting from far-flung communities? Get over it, he says. Times have changed.

At one time, if you went to school, got a job, saved your money, and worked hard, the payoff was a little fixer-upper in your hometown and the chance to put down roots. That’s what a healthy housing market looks like, the kind that’s on display across the border in Seattle and Portland. Those cities have manufacturing, major company headquarters, successful startups, old historical buildings that contain thriving shops and galleries—and housing markets that remain linked to local incomes. Houses in Seattle are pricey, but buying one is still a realistic goal, much as it was for professional Vancouverites just a few years ago. A Vancity report, however, says that, by 2025, eighty-five out of eighty-eight high-demand jobs in Vancouver (nurse, police officer, teacher) won’t pay enough to cover local housing—condos and townhouses included.

“It’s sad to see the passing of old Vancouver,” says St. John. But, at the same time, he argues, it’s short-sighted to ignore the fact that BC reaps huge benefits from the money being dumped into the province by mainland investors. They are giving boomers a windfall they could never have imagined—a windfall that’s then passed along to their kids and put back into the economy.

“It just means your economy won’t be doing what you thought it would be doing,” St. John continues. “Now it’s a financial-services and retirement-support and construction economy, and I think that’s okay. I think we should recognize that’s a natural transformation, driven by immigration and the fact that our corner of the planet is a beautiful, stable place with very little corruption.”

But according to Yan, the intergenerational transference of equity is an illusion. Parents are giving their kids a down payment on an overpriced house, which means a massive mortgage that may never get paid off. “One generation has scored—they are the victors in this game. But they’ve shackled their kids and their grandchildren to an albatross of debt.”

And what happens twenty or thirty years from now, when the last boomer cashes out? When huge pockets of the city and the region are controlled by wealth generated in another country? When there is no financial district, little manufacturing, and no industries other than those that cater to rich people?

Stripped of civic culture, the city becomes a seaside resort ossified by wealth. Few historic buildings remain. The east side is densely packed, having been carved up into blisteringly expensive duplexes, laneway houses, and granny suites. The west side is effectively a gated community. The downtown has been overtaken by multimillion-dollar condos in skyscrapers, high-end chain stores, and luxury car dealerships. With so few mom-and-pop businesses, pubs, or cafés, the core is dead at night—the streets, empty wind tunnels.

In this dystopia, nobody talks about the crazy house prices anymore. Vancouver isn’t even on the radar of the average wage earner. The middle class has been hollowed out. With nowhere else to go, the city’s citizenry has pushed inland, filling up acreage in the east and to the south. Residents in need of space—elderly boomers, immigrants, young families—have settled in formerly pastoral areas of Surrey, Langley, and Chilliwack and now live in massive townhouse developments. The bulk of the population has grown around bustling transit hubs such as Surrey City Centre, Coquitlam Centre, and Burnaby’s Brentwood and Metrotown. They are the new glass-tower cities, the new urban cores.

As for Vancouver, there is not much reason to go there—unless you work in the service industry, or you go to UBC, or you have guests in town. It’s a knock-off Monaco, where you drop by to enjoy the view.

This appeared in the May 2016 issue.