I am staring into the eyes of Harry Houdini. Here he stands, taller than me, with arms casually folded. I move closer to determine the colour of his irises. Our faces are just centimetres apart. Then it happens: he blinks.

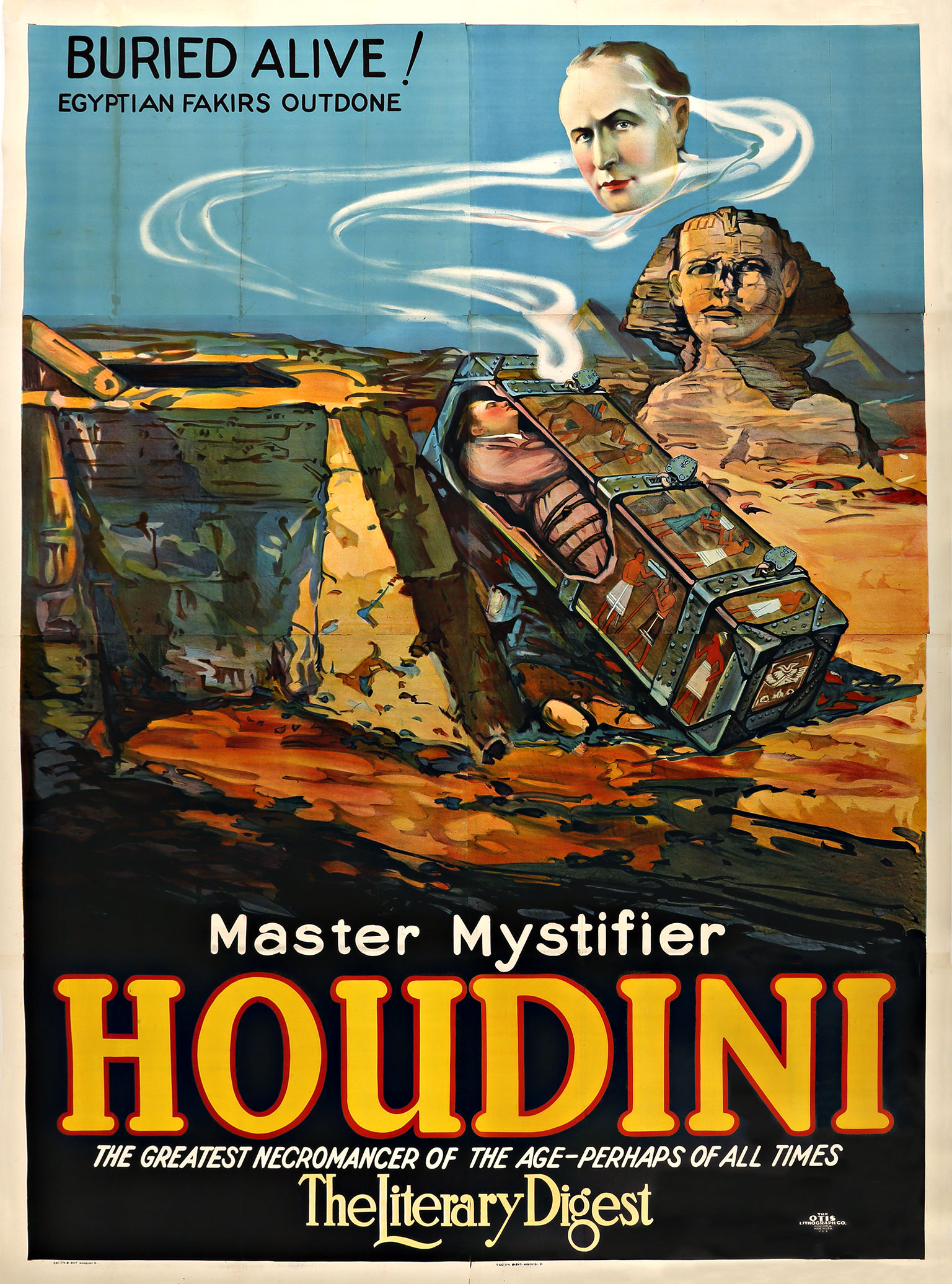

I shake my head and step away from this pristine, larger-than-life poster. It’s only advertising, I tell myself. It was printed in 1911, fifteen years before Houdini’s death. This is just an original, immaculately preserved, two-metre-tall lithograph. On the opposite wall, towering above me, is a billboard-sized poster of the Master Mystifier’s illusion “Buried Alive.” I’m standing still in the basement of the McCord Museum, in Montreal, and the room starts to spin. The importance of what has happened becomes clear: this place just took delivery of what is easily among the world’s most important magic collections.

The lot is worth $3 million and is especially strong in so-called Houdiniana. More than 1,000 items—rare books, personal correspondence, playbills, photographs, autographs, notebooks, and ephemera of all sorts related to the Handcuff King—are being carefully catalogued in another part of the museum. In this room, Houdini is surrounded by 600 exquisite advertisements announcing the most illustrious performers in magic history.

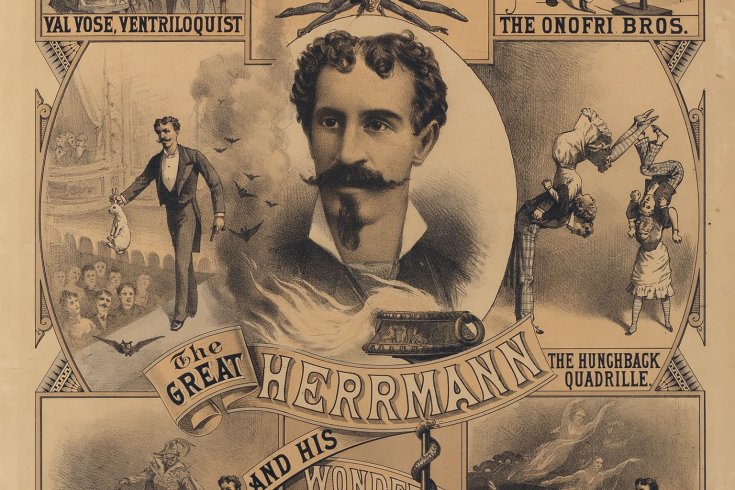

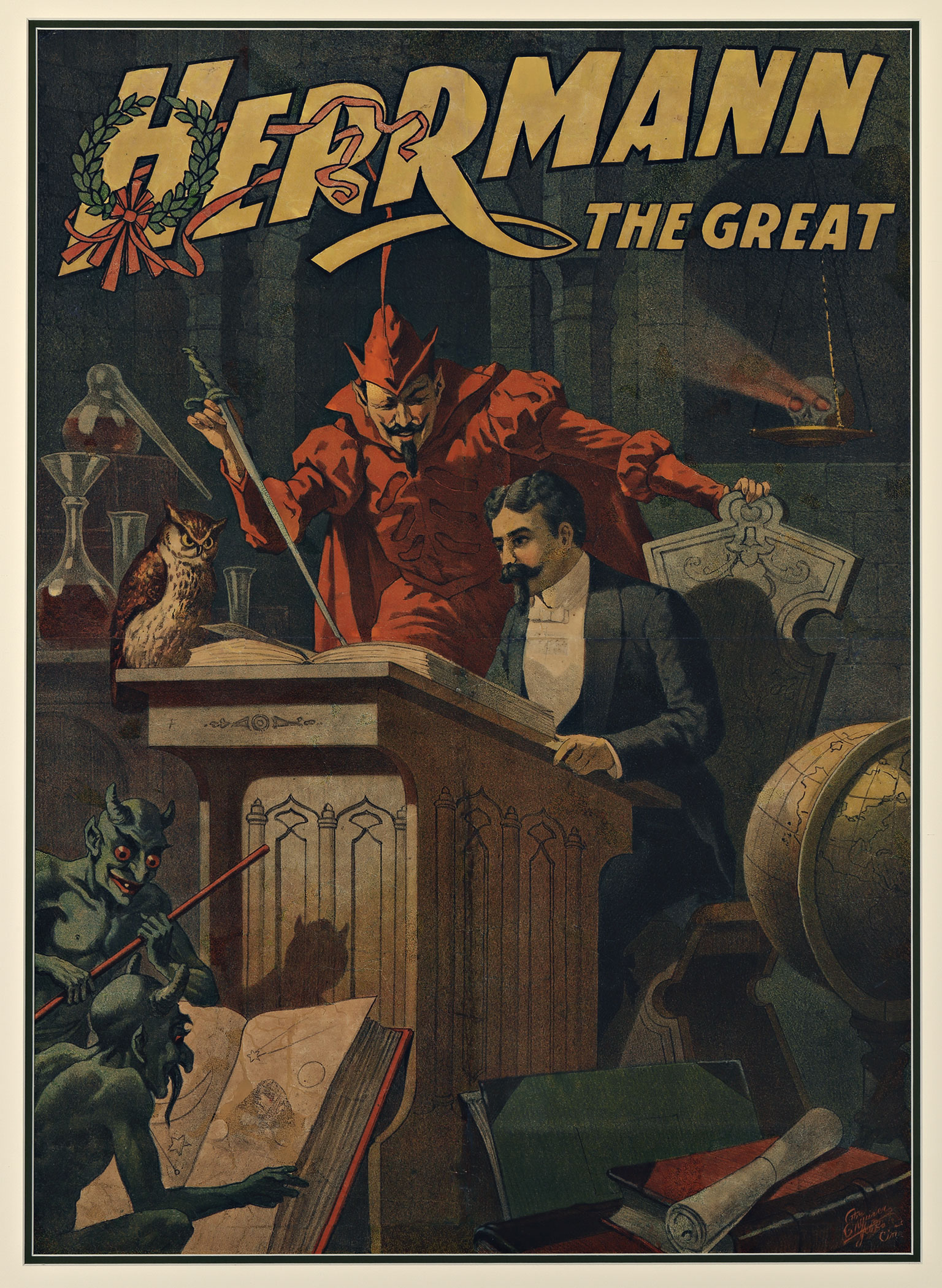

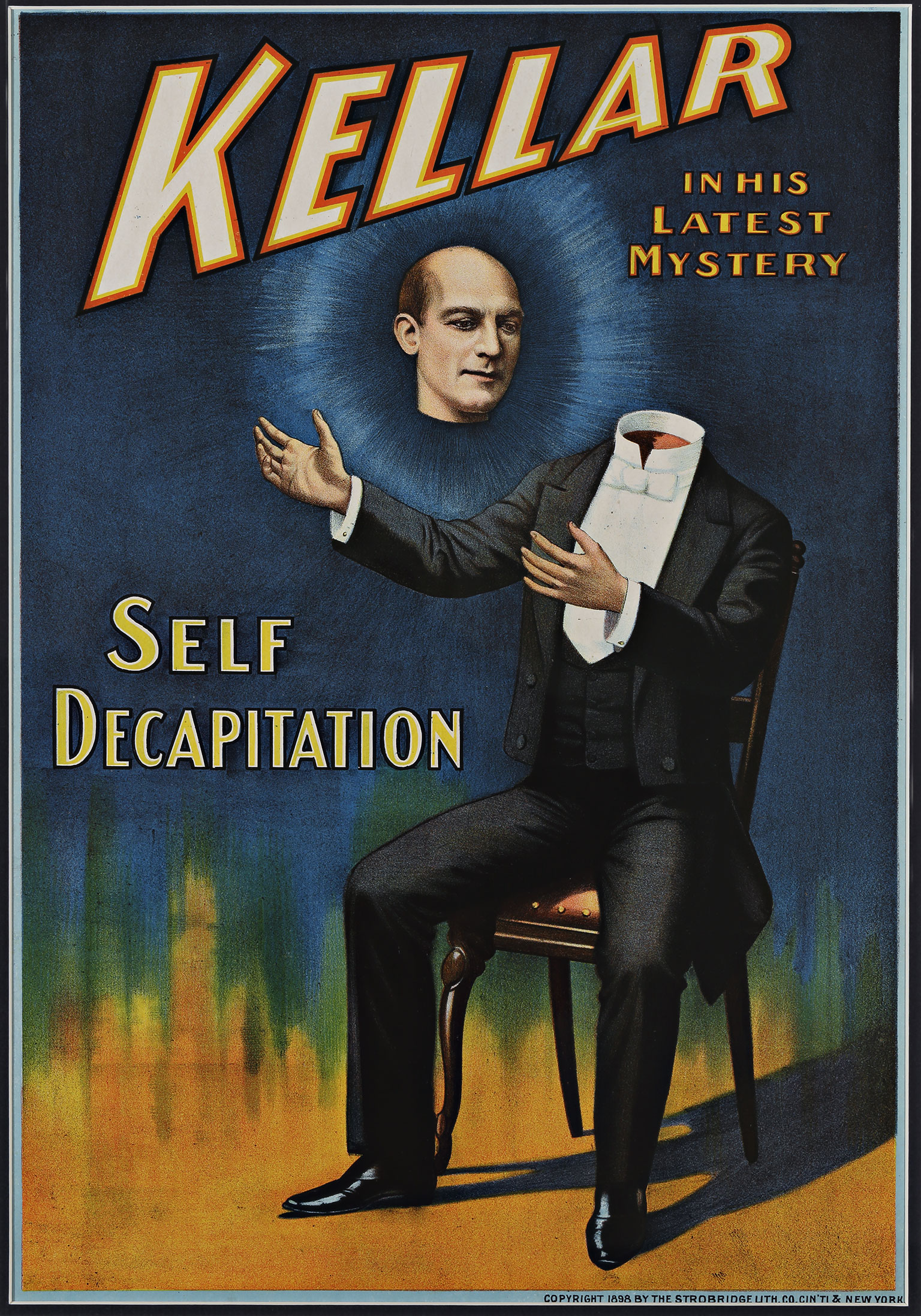

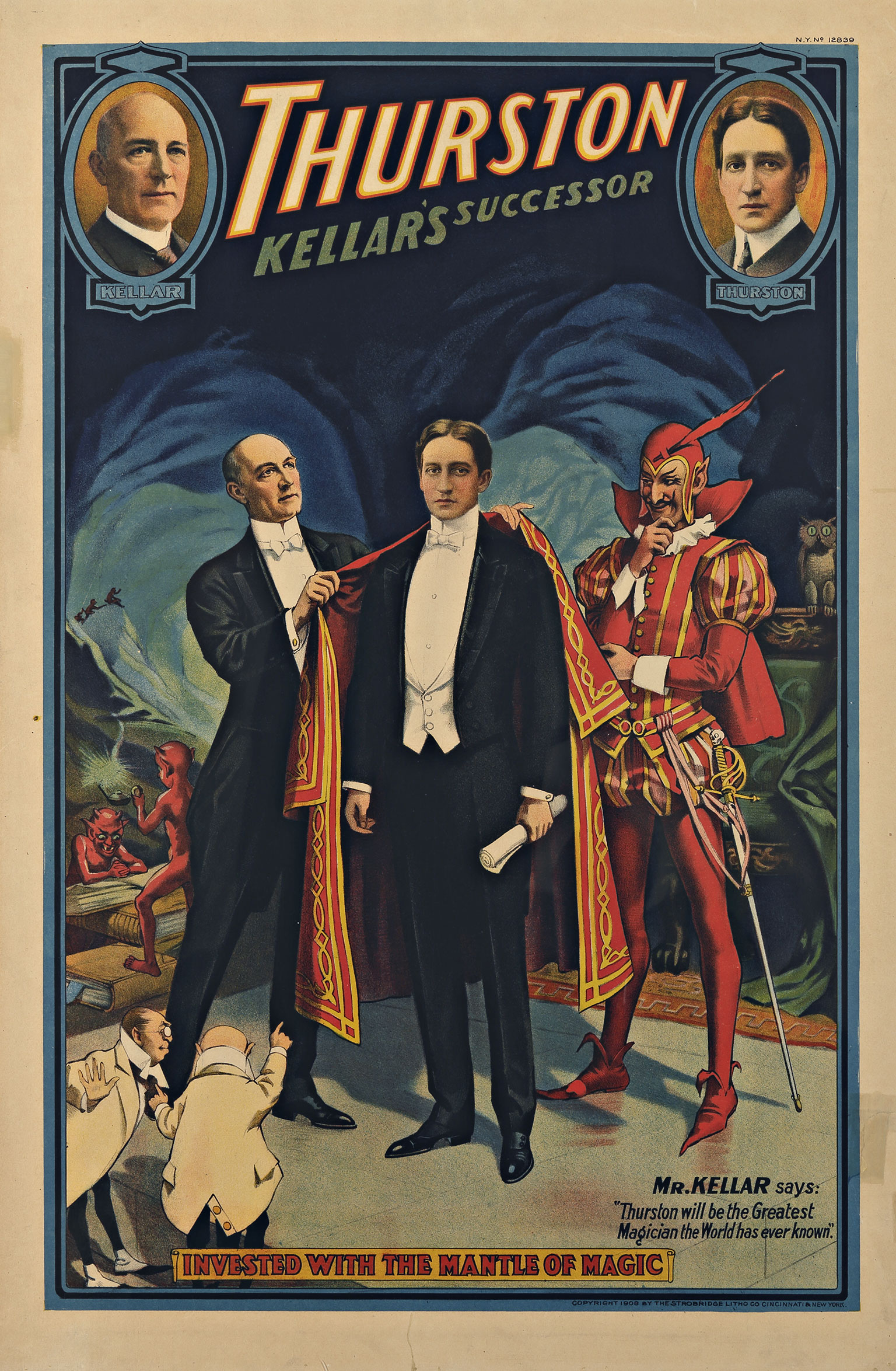

Magic’s golden age lasted roughly from 1875 to 1925. Superstars such as Alexander Herrmann, Harry Kellar, Howard Thurston, and Houdini strove to draw the largest crowds to their shows. Their duelling performances required publicity materials to match—materials that helped construct a powerful celebrity system that predates Hollywood. Before we had movie stars, we had magic stars.

These posters document, with clarity and elegance, the magical fantasies of turn-of-the-century spectators. One theme in particular—the promise of life after death—continues to resonate today. Many of these posters tantalize viewers with the magician’s power to transgress the limits of mortality.

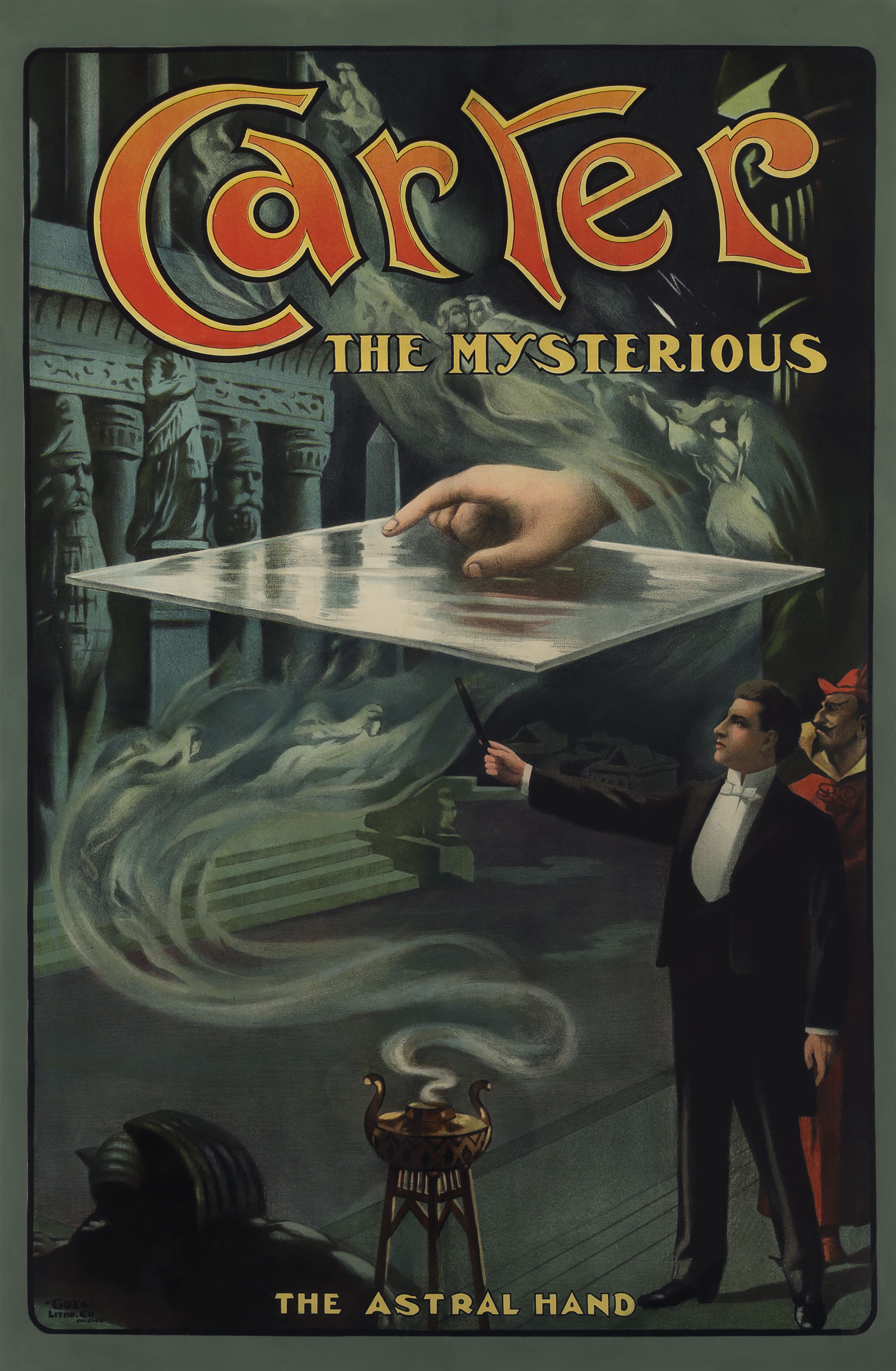

What arcane knowledge is Herrmann the Great reading from the tip of the devil’s sword in The Book of Life? How does Carter the Great’s “Astral Hand” move of its own accord? Does Kellar really self-decapitate? If so, did the imps that sometimes appear on his shoulders tell him how to do it? These are some of the otherworldly riddles posed to passersby. They can be distilled into the question emblazoned on one of Thurston’s house-sized posters: “Do the spirits come back? ”

The turn of the century saw a sharp rise in seances, the introduction of the Ouija board, and the zenith of spirit photography. The public looked to the world’s great magicians to confirm or deny the claims of spiritualism—the belief that communication with the dead is possible.

The spiritualist movement began in the 1840s with the spirit-rapping tables of the Fox sisters in New York (at least one later admitted their hoax). It continued with international demonstrations by the Davenport brothers of their sensational spirit cabinet. The two men would be bound by ropes and enclosed in a large box with musical instruments; spirits would then be summoned and the instruments would begin to play. When the cabinet was opened, the Davenports would still be tied at the hands and feet. Over the course of twenty years touring North America and Europe, their performances were exposed and duplicated by a number of magicians whose posters appear in the McCord collection. Magicians today face a similar ethical choice: Do you claim supernatural powers in real life, or do you simply perform the illusion of such powers onstage?

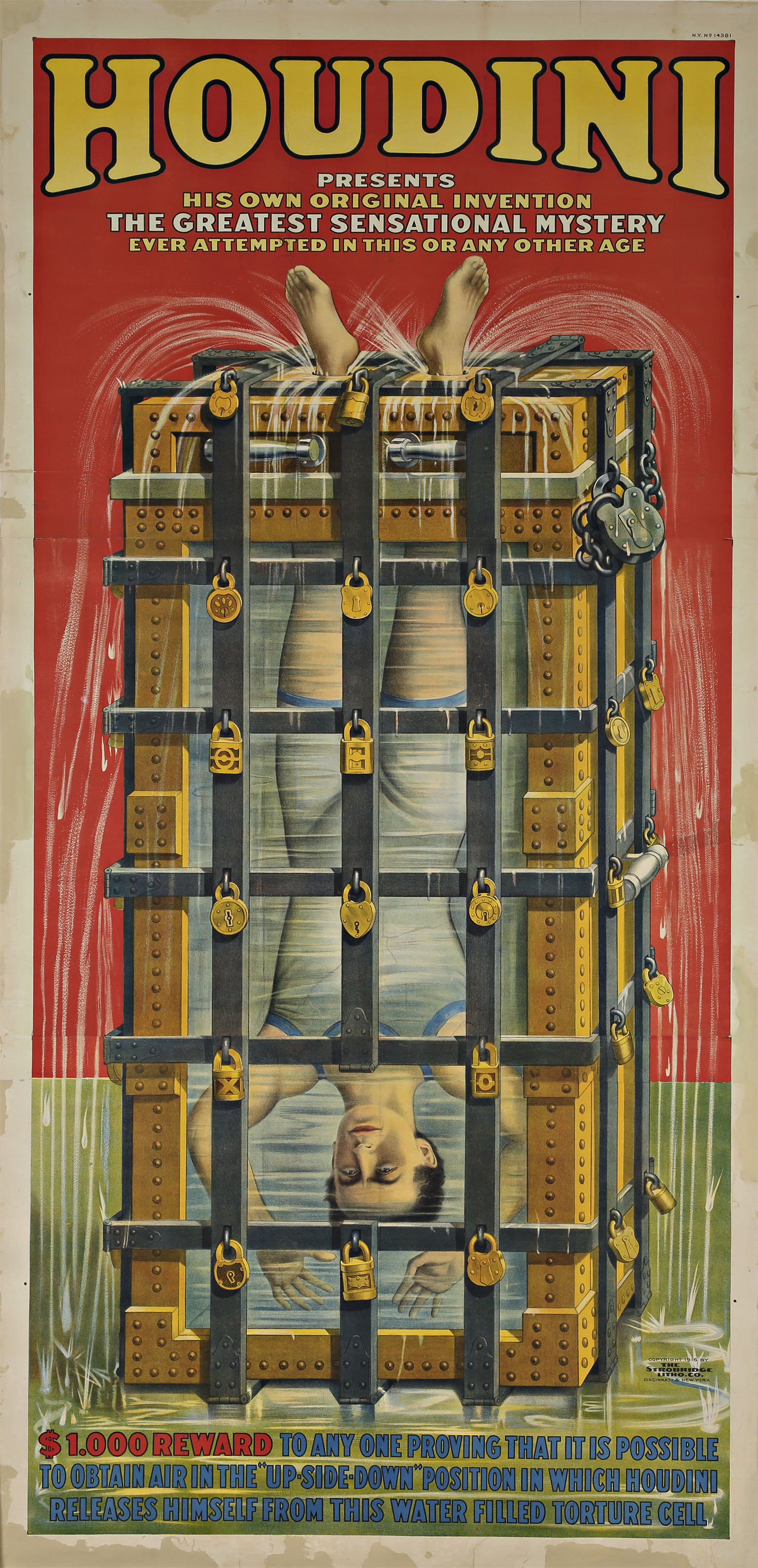

Houdini was a high-profile opponent of spiritualism. In 1911, he interviewed the surviving Davenport brother to learn how he escaped from the ropes. From the early twentieth century until the end of his life, Houdini emphasized the physical prowess his escapes required. He vehemently denied having occult powers. He shunned the Davenport path. Though he continued to employ otherworldly imagery in his promotional materials, his artwork and publicity stunts focused on the power of the ordinary man—of the human body—to achieve the impossible. He challenged the public to build handcuffs and packing crates from which he would be unable to escape. And while he filled theatres with these other forms of publicity, he also gave lectures debunking spiritualism.

Houdini delivered one such lecture at McGill University, in the student union ballroom, mere weeks before his death and the end of the golden age. That room is now the library of the McCord Museum. It’s empty at the moment, but full of magic.

This appeared in the April 2015 issue.