Rosedale Valley Road is a tree-lined sanctuary that winds through the ravined heart of Toronto. For Nigel Wright, it’s part of a half-marathon route he used to traverse virtually every day, but one morning nine years ago its calm was abruptly shattered. Just after five a.m., a German shepherd came charging at him out of the trees. Within moments, three other equally ferocious dogs were also upon him. There was no traffic, nor any apparent avenue of escape. “They started working as a pack,” Wright said in a news account of the incident, “coming around me from all directions. I was extremely aggressive. It was absolute survival and an animalistic response. I really thought that this was it. I absolutely thought I was going to die.” Suddenly and serendipitously, a cab appeared and Wright, who had been kicking frantically at the dogs, managed to flag it down just as their owner emerged from the underbrush and called them off.

A “wrong place at the wrong time” kind of event, but the next morning Wright was probably back on the roads. Obsessive about fitness and long inured to the loneliness, the dark, and the vagaries of weather, he runs at a brisk pace—usually twenty kilometres in about 100 minutes. He runs early because that’s when he has time. By seven in the morning, he is at his desk for the start of a second half-marathon, a fourteen-hour day punctuated with work by other names: evening staff meetings, social receptions, and a few armloads of professional reading.

He has been running like this—an average of 120 kilometres a week—for twenty-five years. Until he arrived in Ottawa last fall, he had trained mainly in the neighbourhoods around his downtown Toronto home, although he also runs while travelling on business: the United States, Europe, Africa, Asia, across dozens of alien landscapes. Here’s the basic math: twenty-five years at 120 kilometres per week makes more than 155,000 kilometres. It would be a mistake to regard this statistic as trivial, or to view his running as merely a casual discipline; it’s more than that—a ritual as sacred in some respects as a religious practice.

Indeed, if he were to talk about running, he would doubtless describe its benefits as being as much spiritual as physical—the quest for a Zenlike state in which a stress imposed on the body confers relief of the spirit. At least publicly, however, he isn’t talking about running—nor anything else. In the spring of 2010, Prime Minister Stephen Harper, an old friend, invited Wright to take an eighteen- to twenty-four-month leave from one of the top jobs on Bay Street to become his chief of staff in Ottawa.

It was an invitation that implied no small amount of sacrifice. Wright was a managing director at Onex Corporation, the private equity Goliath and—after the federal government—the country’s largest single employer. Although Onex does not publish details of executive compensation, it is widely believed that his gross annual income in salary and bonuses exceeds $2 million; on Parliament Hill, it’s unlikely that he will earn more than $300,000. Still, Harper’s summons was a call to public service he felt he could not refuse. We live in an age grown properly skeptical of such conceits—noblesse oblige lite—but Wright’s, it happens, is genuine. In many ways, he’s a throwback to another era. He developed an appetite for politics in high school: at seventeen, he wrote a well-reasoned letter to the editor about the flaws in Pierre Trudeau’s constitutional patriation proposal, and it was published in the Globe and Mail. Even then, his preference was more for the meat of public policy than for the seamier side dish of campaign tactics, and it has never really left him.

Nor was his interest simply academic; he sought engagement. In university, he threw himself into the Young Conservatives, backing Brian Mulroney’s leadership campaign in 1983. Greg Lyle, another young Tory at the time, recalls that he found meeting Wright “pretty intimidating. It was incredible how smart he was. He really knew his stuff.” Tom Long, who as president of Ontario’s campus Conservatives led 300 delegates at the convention, recalls that “our bloc ended up being the difference between Brian and John Crosbie on the penultimate ballot. Nigel was a key part of that.” Writer and commentator David Frum, who also met Wright during those years, says, “Nigel was the Conservative’s conservative, but in a very subtle and nuanced way. He saw beyond the Reaganite, Thatcherite slogans of the day. He saw how the Canadian experience was similar and how it was different.”

Still, Wright’s economic instincts—freer trade, lower taxes, less intrusive government—were always identified with the party’s bluer, more libertarian wing.

In Ontario, he led a small cadre of policy planners who worked on Mike Harris’s unsuccessful 1990 campaign, and later played a formative role in the birth of the Reform/Alliance movement. When Tom Long launched his bid for the leadership of the Canadian Alliance Party, he says, “I immediately called Nigel, and he helped me paint a comprehensive picture of how the world works, how domestic policy works; here’s the policy matrix you need to be thinking about. It was like going to school and getting a crash course.” After Long lost to Stockwell Day, he turned once again to Wright, to help raise money to eliminate Long’s campaign debts. (The two have remained close friends; Wright is godfather to Long’s son, Michael.)

Later, Wright was among those who encouraged Stephen Harper to seek the leadership of the newly united federal party. Since that merger in 2003, Wright has continued to play an active—albeit backstage—role, as a productive fundraiser and a valued policy adviser to Harper and other senior Conservative politicians. Even before tapping him to join his staff, Harper was in touch with him on policy questions. Wright used to sit on the board of the Manning Centre for Building Democracy, run by former Reform Party leader Preston Manning, an affiliation that gave him a foothold in the two principal factions of the broader party: the more ideologically driven Western element, of which the Manning Centre is at the forefront, and the more pragmatic Eastern group that has effectively seized the levers of party power.

He began work in the Prime Minister’s Office last November, in tandem with outgoing chief of staff Guy Giorno, and became the sole, official gatekeeper on January 1. But the low profile remains; these days, if he consents to any interviews, it will be to trumpet what he perceives as the virtues of Stephen Harper’s Conservative government, not to talk about himself. (He declined to be interviewed for this article.) But he continues to run most mornings, and if you rise early enough you may spot him sprinting through the spectral, frozen wastes of the capital. Look closely. As he helps steer the unstable vessel of Harperism toward the next federal election, one eye, at least metaphorically, is cocked for signs of trouble—mindful of both the government’s many political enemies, and those dogs on Rosedale Valley Road that would happily have eaten him for breakfast.

Although he has spent the past thirteen years at Onex, and about seven before that practising merger and acquisitions and securities law at Davies, Ward, and Beck, one of the country’s most prestigious commercial firms, Nigel Wright’s recent government secondment is not his first direct encounter with Ottawa’s favourite blood sport. In 1984, and barely into his twenties, he took a phone call from Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. Would he consider taking a hiatus from law school at the University of Toronto to work as a speechwriter and serve as assistant to Charley McMillan, the PM’s senior policy adviser? Wright consulted the school’s dean, Robert Prichard, who urged him to take the job, notwithstanding the inevitable delay and complication of his legal training. But the chat with Prichard was mostly about observing protocol; Wright had already made the decision. As he told his Trinity College friend Kevin Adolphe, “I feel a duty to the country.” From any other bright young college student, this might have sounded pretentious or simply inane; from Wright, it was totally sincere.

In Ottawa, he roomed in a downtown apartment with Tom Long, who was working elsewhere in the PMO. “We lived together, but I rarely saw him,” recalls Long. “Nigel worked incredibly hard, late into the evening, and then he’d be up at some ungodly hour working some more.”

One night, Wright and McMillan were staying late in the Langevin Block, across from Parliament Hill, preparing the prime minister’s notes for the next day’s cabinet meeting. It was 8:30 p.m., half an hour before their deadline, when the hotline on McMillan’s desk lit up: it was an aide from Mulroney’s office, asking if the material was ready.

“Almost done,” Wright assured him. Two minutes later, the phone lit up again. Wright impatiently grabbed the receiver and, only half in jest, barked, “Will you fuck off!” Only this time, it wasn’t an aide at the other end; it was Mulroney himself. Unfazed, the PM slipped into his signature basso profundo and crooned, “Could you please put Charley on the line? ” And for what was possibly the first and last time in his life, Nigel Wright was left, momentarily at least, cringing with embarrassment.

An old and amusing story, of course, but one that, in the peculiar way the world sometimes turns, acquired a contemporary relevance when Wright, now forty-seven, returned to the Langevin Block last fall.

In recent years, the PMO has grown dramatically in size and power. The chief of staff functions like a consigliere: as well as calling signals for every offensive and defensive manoeuvre and controlling information flows, he’s the PM’s sounding board and last line of defence on every significant matter. “The important detail about Nigel,” says David Frum, “is that he’s ultra fair minded. His role isn’t to put his own thumb on the scale in terms of what gets presented to the prime minister. In other words, I don’t think you get these jobs unless you do have strong views, but you can’t succeed unless you’re able to put those views to one side. Nigel can and will.”

In the best of political circumstances, the chief of staff has the second-toughest job in Ottawa. University of Toronto political scientist Nelson Wiseman says it requires “a massive skill set. You’re overseeing 120-odd people, liaising with the Privy Council Office, dealing with the party caucus and the regional desks, coordinating four or five policy people and half a dozen speechwriters. Essentially, you’re the eyes, ears, and nose of the prime minister, and you have to be a very quick study.” Under Harper, an obsessive-compulsive micromanager who has brooked no serious opposition to his thinking (he’s been known to rehearse the remarks of his own ministers at cabinet meetings, in preparation for question period in the House of Commons), the job will likely be even tougher.

Among the nomenklatura of official Ottawa, Tory and otherwise, the proposition that Harper stands in serious need of an adviser unafraid to speak truth to power is thus widely accepted. Certainly, it’s safe to say that during his first four and a half years in government, the two previous chiefs—Ian Brodie and Guy Giorno—were seldom understood to dare say to the prime minister, “With all due respect, sir, that would be a stupid, suicidal, insane, mendacious, vindictive, counterproductive decision.” Harper cabinet members have felt similarly constrained to suppress any critical reflux they might have felt bubbling up on policy matters. As Globe and Mail columnist Lawrence Martin noted in his aptly named 2010 book, Harperland: The Politics of Control, Harper ran the PMO and the cabinet like a schoolroom, where he was the stern headmaster and everyone else was there to learn and submit to his will and authority.

Brodie, the political scientist who served as chief of staff during Harper’s brief tenure as leader of the Opposition, and for more than two years after the first Conservative electoral victory of 2006, was seen as an affable but obedient henchman, orchestrating the Harper-inspired program to ruthlessly control all aspects of the government’s political message. It was Brodie who was dispatched to exact sweeping editorial changes on Harper’s Team, a book by former strategist Tom Flanagan about Harper’s rise to power. It was Brodie who ordered then Conservative MP Garth Turner to cease and desist from public criticism of the party’s decision to recruit Vancouver Liberal David Emerson to the cabinet as trade minister, just days after the 2006 election. (Turner, characterizing the Emerson appointment as unprincipled, subsequently crossed the floor in the opposite direction.) And it was Brodie who took the heat for putting a very clumsy toe in the waters of American presidential politics, after disclosing to the media that Barack Obama had not been serious in calling for renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement during campaign appearances in the Rust Belt states. That faux pas, in February 2008, may have been fatal; Brodie’s departure was announced the following May.

More combative than Brodie and even more committed to hardball tactics, Giorno, a former Mike Harris loyalist and aide, was blamed for pushing Harper and his government into a series of costly political gaffes: the messy 2008 measure, later revoked, to eliminate federal party subsidies, which nearly brought down the government; the PM’s controversial and arguably undemocratic proroguing of Parliament in December 2009; the embarrassing foofaraw over the decision to scrap the mandatory long-form Statistics Canada census; a steady attempt to politicize the Privy Council Office, traditionally seen to offer non-partisan advice; the awkward handling of cabinet member Helena Guergis’s firing, after revelations that her husband, former Conservative MP Rahim Jaffer, had engaged in lobbying activities; and the attempt to block the release of uncensored documents in the controversy surrounding Canadian forces’ handling of Afghan detainees. Following Giorno’s arrival on the scene in 2008, an op-ed piece noted that, as one of the architects of Harris’s Common Sense Revolution, he was “not the ying to Mr. Harper’s yang. Rather, they are two yangs together.”

Nigel Wright is cut from a different cloth entirely. In modern times, the best analogs to the gravitas he brings to the PMO would be Derek Burney, Brian Mulroney’s chief of staff in the late 1980s; and Jean Pelletier, who served in that capacity under Jean Chrétien in the ’90s. Wright can claim none of Burney’s prior experience as a Canadian diplomat, but his curriculum vitae at Onex implies a grasp of global economic currents unmatched by virtually any previous incumbent. And though he is not as close to Stephen Harper as the late Pelletier was to Chrétien, he likely commands the same kind of respect. “Nigel has a long-standing relationship with the prime minister,” observes veteran Tory strategist Jaime Watt. “They know each better than people recognize. They both know what they’re getting into. And Nigel is not subservient. He’s demonstrably a peer, close to Harper in age, and has a long record of accomplishment and community service.”

Of course, it’s been almost two decades since Wright last worked in Ottawa’s insular political hothouse, but that, too, may confer an advantage. Instead of being drawn into the miasma of tactical gamesmanship and wedge politics that preoccupied Giorno, he’ll keep vigil on the bigger strategic picture. “When you’re there,” explains another friend, writer and broadcaster Rudyard Griffiths, “you tend to look at the outside world as if through the slit of an army tank. It’s a very narrow window. Nigel, in addition to his deal-making savvy, will bring a different perspective.”

On news of Wright’s appointment last fall, the brigades of partisan snipers quickly loaded their weapons. Liberals, New Democrats, and the Bloc Québécois criticized his right-of-centre political leanings, bemoaned his ties to the pernicious demigods of big business, and warned of potential conflicts of interest between sectors he handled at Onex (principally aerospace, defence, and energy, but others as well) and files he would likely be called on to stickhandle through cabinet.

He was summoned before the parliamentary ethics committee to defend himself against the assumption that his advisory utility would be effectively neutered by his prior corporate connections. Of particular concern were his directorial ties to Onex-owned Hawker Beechcraft Inc., a partner with Lockheed Martin in a consortium that is selling F-35 stealth fighters to Canada for $16 billion in an untendered contract. “He’s in a completely untenable position,” complained Winnipeg NDP MP Pat Martin. “[It’s] a… profound conflict of interest on so many levels that in order to live up to any ethical standards, he would have to recuse himself from three-quarters of cabinet meetings. He would be out in the hallway more often than he would be in the cabinet room… [He] cannot even order a pizza for the prime minister without being conflicted.”

A clever sound bite, of course, but otherwise nonsense. And Wright was prepared for it. He had already paid a visit to federal ethics commissioner Mary Dawson, and had drafted the terms of an “ethical wall” that would screen him from any direct dealings between Onex and the government. He had also agreed to exempt himself from all discussions involving the Canadian aerospace industry, since he had sat on the boards of Hawker Beechcraft Inc. and Spirit AeroSystems Inc., both Onex subsidiaries; as well as from investment industry taxation issues, and the deductibility of interest costs in cross-border investments. A complex mechanism has been constructed to prevent information about these files from crossing his desk. And for the duration of his tenure in the PMO, his public equity holdings, including 93,957 shares in Onex and 44,024 shares of its Cineplex Galaxy Income Fund—worth roughly $3.5 million—have been placed in a blind trust.

In conversation with the committee, Wright appeared poised, polished, confident, articulate, focused, respectful, and utterly nonplussed. For those who knew him, however, the entire “conflict” issue was an exercise in political posturing and opera buffa. Seth Mersky, another managing director at Onex, says he actually laughed out loud when he watched TV footage of earnest parliamentarians grilling his friend. “I have to tell you, it was comical,” he says. “The thought of Nigel ever providing policy advice or action in contravention of the country’s best interests in favour of Onex’s narrow self-interest is simply laughable.” John Tory, another old friend and an astute political observer, calls the parliamentary committee hearing legitimate but unfair: “Nigel’s integrity is complete. The fact is that the first person who would have posed any questions about the potential for conflict would have been Nigel himself. I can assure you that even before he sat down for a substantive discussion with Mr. Harper or anyone else about the job, he would have had prepared for him a detailed, twenty-five-page briefing note containing a complete political and legal assessment of how best to protect the public interest.”

There’s no evidence that such a briefing document was provided, but Tory—not remotely close to Wright on policy questions—is surely right in maintaining that “Nigel is an example of precisely the kind of people we should want to be going into public life.” Indeed, because he has already accumulated significant wealth (in addition to his equity holdings, millions of dollars are said to be parked for him in Onex management’s deferred profit-sharing plan), no one can logically argue that he is using the chief of staff job as a springboard to financial gain.

Because Wright has lived largely outside the klieg lights of the media, significant gaps exist in the public biography. Even old friends such as Tom Long profess to know little about his private life, his upbringing, or the precise origins of his passion for politics. It is known that he was born and raised in a suburb west of Toronto; some friends believe he may have been adopted, but this speculation is unconfirmed. While he remains close to his mother and sister, his father, Graham Wright, a technician, died a few years ago. At the funeral, Wright paid tribute to his father, crediting him for passing on his core ethical and moral values, and for teaching him the importance of public and community service.

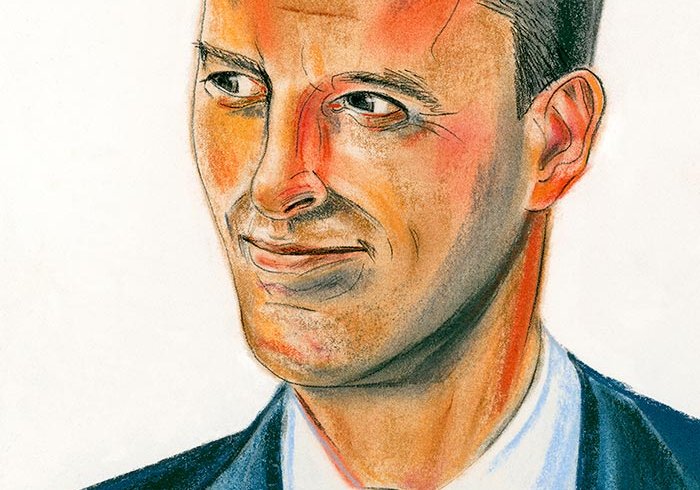

After graduating from law school at U of T, he earned a master’s of law from Harvard, served another brief stint with Mulroney in Ottawa, and worked as policy coordinator during the run-up to Kim Campbell’s 132-day reign as prime minister. Campbell remembers him as “a workaholic, a reliable funnel for policy inputs, and, because of his angelic good looks, quite the catnip for the young women in our office.” It was his subsequent work at Davies in 1996, on an Onex takeover of Imperial Parking, that drew him to the attention of Onex chairman and CEO Gerry Schwartz. “Another managing director, Anthony Munk, told me about him and thought he was extraordinarily capable,” Schwartz recalls. After a series of interviews, the other partners agreed, and Wright joined the firm the following year.

Like other loyal members of the Wright fan club, Schwartz can rattle off a list of his assets: rock-solid integrity, glittering intellectual wattage, fundamental sociability, a prodigious work ethic, and an Ironman durability. “He’s indefatigable,” says Schwartz. “I’ll hear from him from Shanghai one day, Sydney the next. He’s completely selfless. He’ll get on an airplane to fly halfway across the world for a single day.” Schwartz credits Wright with helping articulate and implement the vision that in six years took Onex from a baseline zero position in the aerospace sector to being one of its major private equity players.

One landmark deal was the 2005 acquisition of the Boeing Company’s persistent headache in Wichita, Kansas, a plant that built fuselages and nose cones but suffered from high wages and fractious labour relations. Wright and Seth Mersky thought the Onex modus operandi—slash costs, increase productivity—could generate healthy profits. Everything was going well until Onex asked the unions to accept a 10 percent wage reduction and sacrifice 15 percent of the workforce. At first, they balked. Then Wright and Mersky proposed a sweetening solution: in return for the cuts, union members would receive a 10 percent equity stake in the subsequent initial public offering. The pact eventually delivered $61,000 to each machinist.

Schwartz says Wright informed him of his interest in joining Harper’s staff in the spring of 2010: “On the one hand, we’re very proud of the appointment. On the other, it’s costly for us. It leaves a big hole, though Nigel has mentored a younger group here that can help fill the gap.”

Wright’s principal loyalty, it seems—he has never married, nor been publicly linked with a partner of either gender—has been to his career. His worth ethic is legendary: eighty- to ninety-hour weeks are routine. At Onex, he spent half his life on airplanes, and when negotiating a deal was often away from home for long stretches. Mersky recalls that during the Boeing discussions, he and Wright once spent six consecutive weeks in the Peninsula Hotel in Beverly Hills, dining regularly in the same restaurant: “I’d have a few beers and a hamburger, and he’d have a martini and a hamburger. Every night. At the end, we felt compelled to tell the bar’s management that we weren’t actually married.”

Religion provides him with a second anchor. As a young man, he contemplated joining the Anglican priesthood. Today he’s a subdeacon at St. Thomas’s Anglican Church, near his home in the downtown neighbourhood Torontonians call the Annex. He has been granted semi-private audiences with both the current pope, Benedict XVI, and his predecessor, John Paul II; and a few years ago he accompanied a group led by Father Raymond J. de Souza, Roman Catholic chaplain at Queen’s University, on a tour of holy sites in Israel. Well read on many subjects, he is said to be particularly well versed on religion, and in his early twenties he once spent a long night over dinner at Winston’s restaurant in Toronto, holding his own on the finer points of church history with Conrad Black.

Despite the workload at Onex and his backroom political commitments, he has found time to commit to three major charities: LOFT Community Services, which provides housing for people in need; Out of the Cold, a multi-denominational program for the homeless; and Camp Oochigeas, a remarkable Muskoka facility that caters to children with cancer. As board chair, Wright spearheaded a major fundraising campaign. He still sits on an advisory committee, and, more notably, used to volunteer a week of his summer vacation every year to work with the kids on the site. Until recently, he also sat on the board of the MasterCard Foundation, which funnels millions of dollars into micro-financing ventures in the developing world.

Envoys from the disparate avenues of his life turn up at his home for his much-celebrated annual Christmas party. “These parties are like a Renaissance painting,” says Tom Long. “It’s the most eclectic group you could imagine, because so many people gravitate to him.” Perhaps the most extraordinary aspect of Wright’s life is that he seems never to have made an enemy. This might seem a preposterous claim, especially about someone who has fought, often fiercely, in the war rooms of Canadian politics and led corporate acquisitions that were anything but amicable. And indeed there is no shortage of Liberal and NDP sympathizers willing to lament his unwavering adherence to free market principles and other tenets of the Tory faith. Yet there is something about Wright’s essential persona—a refined gentility, a reflexive courtesy—that seems to disarm potential adversaries. They might disagree with him vehemently, but the differences never descend to ad hominem ugliness.

“I swear to you,” says Phil Evershed, a long-time friend, a fellow conservative, and now head of investment banking at Canaccord Genuity, “the man is well liked by everybody. He’s a pretty strong-willed guy, but he expresses his will in a way that is not particularly confrontational. He absolutely has the courage of his convictions, and he will debate his point as forcefully as anyone, but you’d have a hard time getting angry at him.”

No one is more fulsome in his praise of Wright than Peter Munk, the gold industry baron and philanthropist whose relationship with Wright is friendly but essentially tangential. Munk came to know him through his son Anthony, also a managing director at Onex and a close friend of Wright’s. “In fact,” says Munk, “Nigel is godfather to Anthony’s son.” (Later, when the elder Munk and his wife, Melanie, established the Aurea Foundation, he asked Wright to help frame the ground rules for the semi-annual Munk Debates, which it sponsors.) Munk has been in business for more than five decades. Wherever he goes—and he’s been everywhere—he deals with the elite. Yet he says, “I’d rank Nigel Wright among the mere handful of people I’ve met in whom I have complete trust. He’s just one of those rare human beings with whom you feel totally comfortable in seeking an opinion or discussing complex issues, on any subject. It’s not just his demeanour. You can have a beautiful Cartier watch, and if you put it in a plastic package it becomes a totally different product, doesn’t it? But with Nigel, the demeanour is accompanied by a fundamental intelligence.”

Tom Long believes it is Wright’s experience as a Bay Street deal maker that will ultimately best serve him—and the prime minister—in Ottawa. “The key thing is the ability to filter. As a private equity guy, you might have 500 good ideas, but you then have to screen them, identify the two or three worth spending time on. You have to assess the competitive environment any company is working in, what the structural issues are, the growth characteristics, and where can you add value other people don’t see. The guys who can think in three dimensions the way Nigel can are typically the ones who are successful.” Calling Wright “among the very best and brightest of his generation,” Robert Prichard, who now sits on the Onex board, predicts Stephen Harper will soon be pinching himself and asking, “Where has this guy been all my life? ”

During his appearance before the parliamentary ethics committee, Wright declared that Harper’s “values align with mine in every conceivable way.” Incontrovertibly, he was enlisted as chief of staff because, a priori, he views the matrix of public policy through the same ideological lens as the prime minister does. The careers of the few Tory dissidents who have had the temerity to protest Harper’s Way have been given a one-way ticket to political oblivion. But after five years in power, perhaps Harper has realized that turning the cabinet and the caucus into an echo chamber, where every opinion is a sycophantic variation of his own, is not the optimum way to govern. Wright’s appointment could be seen as a de facto acknowledgment that dialectic trumps monologue. Total command of his sad chorus of yes-men has yielded what? Two minority governments, a pathetic standing east of Ontario, and the enduring skepticism of Canadians that the Tories should be trusted with a majority.

If Wright is as capable as his record and his friends suggest, he will bring a new measure of stability to the PMO, and rechannel Harper’s energies away from divisive small ball and back to pursuing the grander Conservative vision that first inspired them both. “Nigel won’t nod his head and acquiesce to weak ideas,” insists his friend Greg Lyle, managing director of Innovative Research Group. “It’s not in his nature to flatter anyone, least of all superiors. He’s a very disciplined, ruthless thinker. You can’t make an argument with a loose end and not expect him to find it and yank it. He’s too good. There’s no one smarter than Nigel. He’ll be gracious, but he will speak truth to power.”

That, surely, is the heart of the matter. He will be asked for advice on dozens of issues, among them how best to navigate the treacherous shoals of a shaky economy; how to position the party’s policy on the environment, crime, and other incendiary files so it can finally capture a parliamentary majority; how to finesse Liberal Opposition leader Michael Ignatieff, the NDP’s Jack Layton, and Gilles Duceppe and the Bloc Québécois. But ultimately, the singular question that hovers over Wright’s appointment is whether he will have the cachones to say deliberately to a sitting prime minister what he once said unintentionally to Brian Mulroney: fuck off.

Stephen Harper may have the smartest guy in the room on his speed dial, but it would be folly to regard Wright as a deus ex machina, a man able to undo the government’s missteps or save the prime minister from his own sometimes wayward instincts. Still, if Harper can’t secure his elusive majority with Nigel Wright as his corner man, it’s a safe bet he never will.

This appeared in the April 2011 issue.