I’m a bit of a recluse. It comes with the job of writing books. I live with my husband and our two middle-school children in a canyon in the Santa Monica Mountains in southern California. Between school drop-off and pickup I’m a novelist. I sit alone in my pajamas with crazy hair and a mug of tea conjuring characters and inventing narratives that I hope to share with strangers, which sounds psychotic. When I’m not in a typing trance I’m a wife and mother, like any other, caring for my family, driving my kids to practices and dances and games and rehearsals. Sometimes my hands hurt from all the tapping on the keyboard and gripping of the steering wheel but I count myself exceedingly fortunate and grateful for my lot.

A number of years ago I started to feel stiffness in my finger joints. I mentioned to my husband that I thought I was developing arthritis and he said something about all my years of writing taking their toll. Overhearing this, my daughter, then around eight, looked at me with concern and asked, “Is ‘authoritis’ why you make that face? Will it stay like that? ”

We all knew the face she was talking about. My son calls it my faraway face—the half-there stare and the deeply furrowed brow and the cocked ear because I’m trying to hear the characters still chattering in my brain. The three of them do bad impressions of me. When I’m deep in a book they say they have to tell me everything twice. I think that’s what they say—I don’t pay attention. They say I get distracted easily and I’m not always all there. They find me quiet. Sometimes sad.

Authoritis. I suspect the condition affects writers in all mediums. My daughter’s misunderstanding of the word made me think about the way I spend my days. At best, writing is an addiction. At worst, writing is an addiction. I’ve heard people speak of golf and other solitary pursuits this way. Whatever story I’m working on is my drug—I’m always thinking about my next fix. I must actively resist the siren song of my computer, the magnetic pull of my people when the writing day is done—hence the furrowed brow and faraway look. There have been occasions when only fear of an encounter with a wild animal has kept me from my computer at 3 a.m. (the garage over which I work is twenty very dark steps from the house).

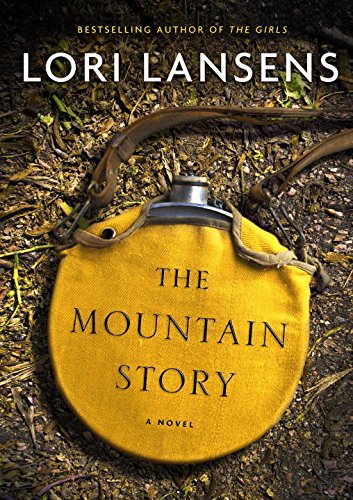

Many of us work in a vacuum. No daily feedback. No weekly feedback. In my case, no yearly feedback. I worked on my current novel, The Mountain Story, for nearly four years before I let my husband read a rough draft. Isolation was part of the process—I needed to be alone with my characters to write about being lost on a mountain, and I couldn’t let anyone read it until all of the elements of mystery and suspense were in place. Over the five years it ultimately took to write and revise the book—one year for every day that the characters are lost—my husband and children would often catch me wearing that distant expression and ask, “Are you on the mountain right now? ” I was. They’d rescue me, but I wasn’t always thankful.

The writer’s work is sedentary—an unfortunate job hazard. We slouch and slump and tilt and recline. Our discs slip and our vertebrae bulge and still we don’t leave the chair. There’s no lunch with the gang in the break room. No visit to a colleague’s office down the hall. I set alarms to remind me to get up and move around so I don’t get blood clots. Most writers are not at one with our bodies. Our bodies are pissed at us for sitting all day.

I don’t know a lot of writers because of the recluse thing, but I do know a TV writer—a neighbour I see scurrying on the other side of the bushes once in a while. Occasionally he and I meet up at the road with our recycling bins. We laugh about how much we hate talking when we’re in the middle of a writing day. Talking breaks the spell. It takes time to go in deep again—much like a sleep cycle. Most days the TV writer is required to wear something other than pajamas and drive to an office to invent stories with other writers. I’ve noticed his affliction seems less severe than mine.

There is one novelist I met when I was touring with my first book. I bonded with her over the fact that we didn’t really know any other novelists, and saw ourselves as outside of the pack. For a long time I wondered if there really was a pack. I hadn’t seen my friend in years before we had dinner recently and shared our thoughts about the challenges of being writers. We both confessed to suffering from low-grade depression. (I call it melancholy because it sounds more redemptive.) We talked about how false reality feels when we’re required to suddenly and randomly pop back into it. We commiserated over the essential role of solitude in our choice of profession. It’s lonely. We talked about the difficulty of stepping into the light when you’ve been underground for so long, the sudden and swift revelation of the secret you’ve kept for months and years—a baring of your soul. When things got too serious, we laughingly reminded each other that we are volunteers.

The shoptalk was gratifying. Maybe someday science will identify the confluence of factors that drive writers to their novels, poems, screenplays, stage plays, and lyrics. The authoritis? Bet most of us wouldn’t cure it if we could.