Art is a lie that makes us realize the truth.

—Pablo Picasso

On April 7, dignitaries and TV crews made their way down cobblestoned streets to the Stadtmuseum Düsseldorf, a small gallery on the edge of the Rhine River, Germany, to witness the return of a painting the Nazis had compelled a Jewish art dealer named Max Stern to sell in 1937. As a crowd gathered in the building’s assembly hall, a self-portrait by the nineteenth-century Romantic painter Wilhelm von Schadow, a moody three-quarter profile of a cloaked, bearded, windswept man, stared down from an easel on the stage. Although not a work of great monetary value or artistic significance, the painting was revered because von Schadow, an early director of the Düsseldorf Academy, had shaped one of Europe’s most famous art schools, the alma mater of legendary twentieth-century masters including Joseph Beuys, Gerhard Richter, and Andreas Gursky. He had also forged the spiritually charged Nazarene movement, based on the credo “an artist must believe and live out the truths he attempts to paint.”

The von Schadow portrait had previously gone up for auction* on November 13, 1937, at the Lempertz auction house in nearby Cologne—which became infamous for trafficking “non-Aryan property” to Hermann Göring, Adolf Hitler’s deputy and most avaricious looter. It was where Cornelius Gurlitt, the reclusive son of a Third Reich art dealer, unloaded a work by the modern master Max Beckmann in 2011—one of 1,300 paintings in his father’s secret collection. Now, on a sunny spring afternoon in 2014, the von Schadow portrait was being returned to its rightful owner. Or, more accurately, to his estate, because Stern, who would go on to become one of Canada’s most important gallery owners, died in 1987, taking the secret of this and other losses to his grave.

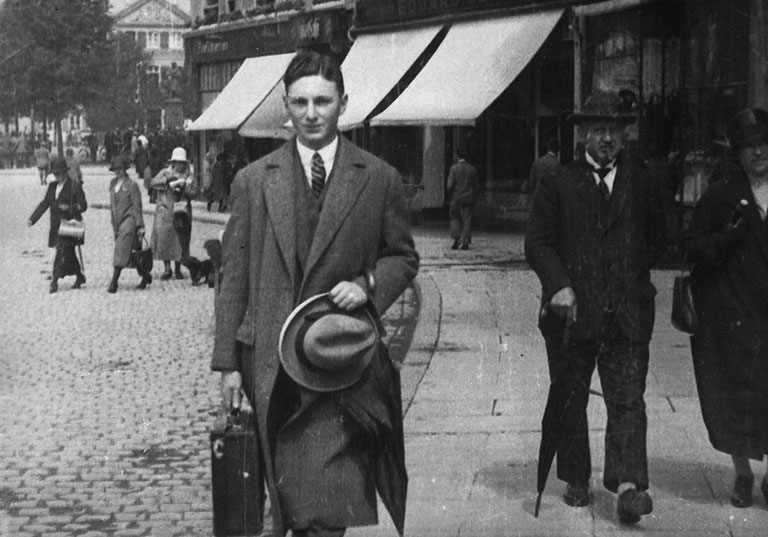

Max Stern’s career as a Canadian art dealer began in the unlikeliest of places: a prison camp. He had escaped Düsseldorf for London in 1937, but in May 1940, when Hitler’s push across the English Channel seemed increasingly likely, Scotland Yard rounded up more than 2,000 German and Austrian citizens, mostly Jews, and incarcerated them as enemy aliens. Stern was sent to an internment camp on the Isle of Man.

Hearing that some detainees were being sent to Canada to free up soldiers guarding British camps, Stern volunteered to join them. In North America, he believed, he would be well-positioned to help his mother and one sister in England, as well as his other sister and her family in France. But Canada, where he was greeted by bayonet-wielding soldiers, was even less hospitable than the United Kingdom. As he recalled years later, “We had to stage a hunger strike to convince the Canadian authorities that we were certainly not Nazis but, on the contrary, anti-Nazi.”

Held in a camp in New Brunswick, he was put to work cutting down trees. Still, he remained optimistic, thankful for the food, shelter, clothing, exercise, and twenty cents per day in pay. He also welcomed the opportunity to teach. Twelve years earlier, he had earned a doctorate in art history, which he now put to use in classes for his fellow internees.

His talent and positive outlook caught the attention of William Birks, scion of the Montreal jewellery family, who headed the local branch of the National Committee on Refugees. Birks was openly critical of Canada’s restrictive and anti-Semitic immigration policy, which he called “narrow, bigoted and very shortsighted.” He believed the government should have sent trade missions to Europe to recruit men like Stern, “not wait for them to seek and beg us.” In 1941, he sponsored Stern’s release and move to Montreal.

Needing a job and hoping to assist in Canada’s war effort, Stern looked for work in an airplane factory. When he was not hired, he turned to the thing he understood best—art. “You’ll starve,” people told him, but he was certain he could be successful as a dealer in Montreal, because he had spotted a void he knew how to fill. Most of the city’s galleries were pushing stuffy nineteenth-century European genre and landscape paintings. No one was promoting or selling homegrown works because, as he later explained, “Canada didn’t have any confidence in its own artists.”

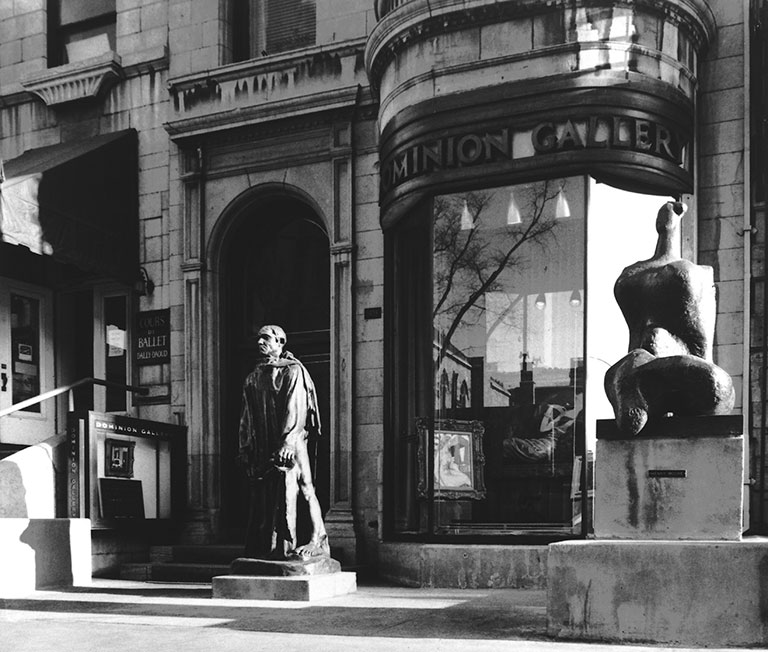

Stern pitched his vision to Rose Millman, who had just opened a space on rue Sainte-Catherine called the Dominion Gallery of Fine Art. Impressed by his assurance and expertise, she offered him a job for $12.50 a week. Stern said he wanted $17.50 and her promise to make him a full-fledged partner once he built up her business by conquering Canada, as he put it, “by selling Canadian artists.”

Within months, he was mounting exhibitions by contemporary Canadian painters. Over the years, they would include John Lyman, Goodridge Roberts, E. J. Hughes, Stanley Cosgrove, Jean-Paul Riopelle, and others whose names he would play a pivotal role in establishing. Stern secured their loyalty and best work by offering them monthly retainers for an agreed-upon number of works, already an established practice in France, England, and the United States, but not yet in Canada.

His first major coup came in 1944, when he visited Emily Carr, then seventy-two, at her home in Victoria. She showed him a room packed with 300 paintings. Struck speechless by her talent, he asked if he could mount an exhibition. Laughing, she replied, “You will not sell a single painting.” The recipient of critical praise, Carr had yet to enjoy commercial success. “If you let me choose the paintings,” Stern replied, “I think I can make it a perfect success.”

He selected sixty canvases, including some from every period of the artist’s career. The exhibition, as he predicted, was a success. When he sent her a cheque for the sales, she said she had never seen so much money. The following year, Carr died and Stern became her estate’s agent. He sold her work quickly and effectively, but kept about forty paintings for himself—the foundation of the significant wealth he would soon amass.

Within three years of joining the gallery, Millman made him a partner, and he took the Canadian art scene by storm. Wartime currency controls made it difficult to export income, so wealthy Canadians were motivated to buy pieces at home. Meanwhile, and for the first time, scholars were documenting the history of Canadian art in books, heightening interest in the works Stern made available to museums and collectors.

In 1946, Stern married Iris Westerberg, a Swedish émigré to whom he was introduced by Birks. The following year, the couple purchased Millman’s gallery outright, and shortened its name to the Dominion Gallery. Four years later, they moved it into a stately greystone building they purchased at 1438 rue Sherbrooke Ouest, where they took up residence in a five-room apartment on its top floor. For the next two decades, he built the gallery with the foresight and conviction he brought to its launch. In addition to selling work by living Canadian artists, he also established a healthy inventory of European paintings, both modern and Old Masters, including works by Picasso, Braque, and Kandinsky. He liked to survey his collection, recount the warnings of the early days, and say with a broad wink, “You can see how I’m starving.”

In the ’50s, Stern took the gallery in a new direction. Predicting that television, movies, and posters would make audiences yearn for the tactile, he made what would become a highly lucrative investment in the works of then little-known British sculptor Henry Moore; and he secured Canadian rights to sell the creations of famed nineteenth-century French master Auguste Rodin, whose popularity had waned in postwar Europe. By the ’70s, the twenty pieces he had bought from Moore for $15,000 had skyrocketed in value, and French dealers visited regularly because he had the largest collection of Rodin’s works outside the Paris museum that bore the sculptor’s name.

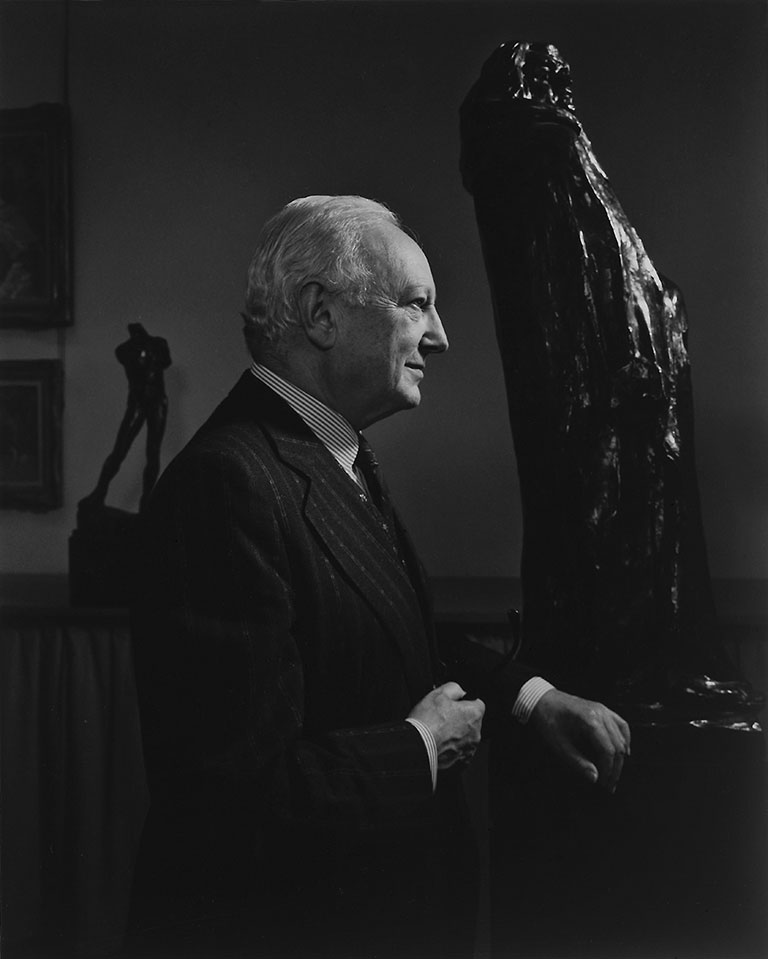

Stern’s success stemmed as much from his smooth and welcoming manner as his art-world foresight. “He was the perfect combination of authority and affability,” says David Silcox, who used to visit the Dominion Gallery in the ’60s as senior arts officer of the Canada Council for the Arts. “He used to introduce himself as Herr Doktor Stern, Ph.D.”—in a thick German accent—“a reminder that he was the country’s only gallery owner with a doctorate. But he wasn’t intimidating, and would talk about art to anyone who was interested for hours.”

Still, there was one subject on which Stern remained silent: his life in Europe. “When asked,” says Charles Hill, curator of Canadian art at the National Gallery of Canada, “he would say, Oh, that’s the past. I’m interested in the present.” And yet in conversations with his clients, he sometimes hinted that there was more to his story, cautioning them to avoid making purchases at auction houses where a painting or sculpture’s provenance was seldom fully revealed and often wilfully obscured. “Pedigree,” he liked to say, “is not only important in animals.”

Stern was still doing what he loved most—dealing art—when he died at eighty-three on a buying trip in Paris. Childless and widowed, he had named McGill and Concordia Universities in Montreal, along with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, as the principal beneficiaries of his estate, which included the Dominion Gallery. Ordinarily, his executors would have been expected to close the gallery, but Stern had requested that it remain open for a decade, if possible—in the end, it survived thirteen years.

In 1999, Clarence Epstein, a Montreal-born, British-trained art expert with extensive experience in art estate management, was selected to oversee Stern’s cultural property, a job that included selling his European collection. Had the works been put up for sale at the time of Stern’s death, they would have disappeared quietly into private collections around the world. But in the decade that followed, the art world underwent a profound transformation. Fifty years after the end of World War II, scholars were gaining access to German archives, and the publication of such books as The Rape of Europa in 1994 revealed a previously untold story about how, for twelve years, the Third Reich systematically looted and deliberately destroyed art on an unprecedented scale. Stolen art was suddenly on the agenda, and provenance was a hot issue.

Not surprisingly, there was an upsurge in claims, the value of the works in question having increased dramatically. In 1998, the Austrian journalist Hubertus Czernin found documents proving that the Nazis had seized Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I by Gustav Klimt, which now hung in Vienna’s Belvedere palace. Ensuing court disputes determined that it was the legal property of Bloch-Bauer’s surviving niece, Los Angeles resident Maria Altmann, and in 2006 a panel of three Austrian arbitrators ordered its return. Altmann subsequently sold it at auction to cosmetics magnate Ronald S. Lauder for a reported $135 million (US).

In 1991, the Art Loss Register, a privately owned database, was established by the art trade (Sotheby’s remains one of its shareholders) to assist those tracking looted or lost works. The ALR, which places all its findings online, quickly became a powerful resource for Holocaust survivors and their heirs in the recovery of stolen works. In 1998, forty-four governments signed the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art, agreeing to search their public collections for looted works and to collectively identify and resolve claims for their restitution. In 2001, the Canadian Museums Association and the Canadian Jewish Congress organized “The Canadian Symposium on Holocaust-era Cultural Property,” which called for a nationwide assessment of cultural collections to find those at risk of holding spoliated property.

This was the cultural climate in which Epstein set about developing a strategy to liquidate the Dominion Gallery’s European holdings. Not wanting to flood the market and thus depress the value of the works, he began conversations with international dealers and auction houses. Invariably, they prompted the question: What was the connection between the Dominion Gallery and the renowned early twentieth-century Düsseldorf dealer Julius Stern? Neither Epstein nor Max Stern’s executors had an answer.

Lucian Simmons, the senior vice-president of provenance and restitution at Sotheby’s New York, provided a clue. Auction houses like Sotheby’s realized they were at risk if they sold objects with tainted provenance—and not only because of public relations considerations. “Once there is a known Holocaust survivor of a known work of art, it becomes virtually unsalable,” ALR historic claims director Sarah Jackson told the Los Angeles Times. Experts like Simmons and his team were hired to trace the origins of the pieces auction houses were asked to sell. They began stockpiling European art catalogues from the ’30s and ’40s.

Simmons sent Epstein one such catalogue, Die Bestände der Galerie Stern–Düsseldorf (The Holdings of the Galerie Stern, Düsseldorf), which included an inventory of more than 200 Old Master and northern European works sold at Lempertz on November 13, 1937, after the Nazis demanded that the Galerie Stern liquidate its assets. “It was clear,” says Epstein, “that we had to find out if Max Stern had been part of the Düsseldorf gallery.”

As part of the liquidation of the Dominion Gallery’s assets, Stern’s private papers—more than fifty boxes of records and photographs—were donated to the National Gallery of Canada. It was there that Philip Dombowsky, the archivist in charge of the collection, discovered the information Epstein needed. Not only was there a connection between the Galerie Stern and the Dominion Gallery; it turned out that Julius Stern was Max’s father.

In the early 1910s, after becoming a successful textile manufacturer in München-Gladbach, the elder Stern relocated to Düsseldorf where he quickly became one of the city’s most important dealers. He bought a location for his gallery on the Königsallee, Düsseldorf’s most elegant and desirable address. On the wide, picturesque boulevard, a canal running down its centre, its sidewalk lined with lush sloping trees, Julius ran his business in the same building where he made his home with his wife, Selma, and their three children, Hedi, Gerda, and Max.

Throughout his youth, Max was groomed to inherit the gallery, which specialized in conservative genre scenes, landscapes, and seascapes, as well as Old Masters paintings and some Impressionist works. He prepared for his future by studying art history in Berlin and Vienna, earning his doctorate in Bonn in 1928. In the last four years of the Weimar Republic, he worked alongside his father, who was generous with his advice. “Don’t give an exhibit of a single period of an artist,” instructed Julius. “Show a cross-section so you can have variety.” This, surely, was what guided Max in his breakout Emily Carr exhibition in 1944. An art dealer must try to know the future and where it is going, Julius told his son, who undoubtedly acted on this admonition when he added sculptures by Moore and Rodin to the Dominion Gallery’s offerings in the ’50s.

Then in January 1932, Hitler gave a two-and-a-half-hour speech at the Park Hotel in Düsseldorf, and the world as the Sterns had known it came to an end. Speaking to more than 600 members of the Industry Club, including some of Germany’s wealthiest men, the Nazi leader allayed fears that he was a radical, and positioned himself as an enemy of communism. A year later, he was chancellor of Germany, and the Nazi Party orchestrated a national boycott of Jewish shops and department stores. A temple in Düsseldorf was defaced with a swastika and the words “Jew perish.” Aryanism became a prerequisite for employment in the civil service. Nazi laws deemed the participation of Jews in German culture as racially unacceptable.

Julius was broken by these events, his health went into a steep decline, and he died in October 1934. As planned, he left the Galerie Stern to his son, but ten months later the Reich Chamber for the Fine Arts sent the younger Stern a letter and copied the Düsseldorf Gestapo. As a Nichtarier (not-Aryan), he had lost his professional accreditation to deal in art and was given four weeks to sell the gallery’s assets.

Dombowsky also brought to light an unexpected piece of information. After the war, Stern began a correspondence with Lester Pearson—then with Canadian External Affairs, as well as a client of the Dominion Gallery—asking for assistance in finding twenty-two paintings he had left with Josef Roggendorf, a shipping agent in Cologne, when he fled Düsseldorf a decade earlier. A statement from Roggendorf provided evidence that the works, valued at £100,000 in 1954, had been seized by the Gestapo.

With the help of Pearson’s political connections, Stern began an eight-year, 32,000-kilometre sleuthing campaign, combing through the cellars of Rome, Cologne, and Vienna, and attracting international press. The Daily Mail in London wrote, “The doctor-detective went to hundreds of sales, advertised rewards in newspapers, poked around half-remembered haunts in a dozen art centres and interviewed scores of dealers.”

And yet, not once in these interactions with journalists did Stern mention the inventory of more than 200 paintings the Nazis had forced him to sell. Why not? As Dombowsky explains, “There was no legal recourse available to him to reclaim the works.” Postwar legislation offered claimants assistance only on works proven to have been confiscated or looted. If a Jew sold a painting to protect it from seizure or to generate income because the Nazis had stripped him of his livelihood, it was considered not a theft but a “forced sale.” Moreover, since Stern himself put the gallery’s inventory up for auction, it is possible he believed that even if it were a forced sale, it was still a sale.

Until 2000, publicity around Holocaust-era restitution claims focused on famous paintings, such as Klimt’s Adele Bloch-Bauer, to which a single individual or family asserted ownership. This raised another troubling issue: since the bulk of the art Jews lost in Nazi Germany was composed of minor pieces sold at forced auctions—as in the case of the von Schadow self-portrait—restitution was addressing only a fraction of what had been stolen.

Epstein began to think about how the Stern estate might augment the understanding of art restitution so that its practice would “honour Stern’s legacy for all the things that he lost and for what he tried to do,” and at the same time serve a larger number of the victims of cultural theft. Although forty-four governments signed the Washington Principles, “none of these countries had yet instituted standard procedures to deal with restitution, and none had a policy for dealing with forced sales.”

In 2002, the Max Stern Art Restitution Project was launched at Concordia. Epstein was named its director (today he also serves as the university’s senior director of urban and cultural affairs). The only restitution organization in the world that is part of a university, it was set up so that the proceeds from its efforts to find and reclaim art could be used to find and reclaim more. A perpetual plaintiff in pursuit of the works listed for sale by Lempertz in November 1937, “we’re an organization that is not going to die,” says Epstein. “Those we approach can either work with us or leave their art to someone else who will be stuck with a tainted piece. But we will never go away.”

Epstein set about building a team. Dombowsky, who would become the project’s lead Canadian researcher, began to compile information on the provenance of each of the Lempertz works by launching an extensive search of German museum catalogues and auction databases. Willi Korte, a Bavarian-born, Washington-based lawyer and war crimes expert renowned as “the Indiana Jones of the art world,” was recruited as its chief investigator. To facilitate international legal claims, the project entered into a partnership with the Holocaust Claims Processing Office, run by the New York State Banking Department, one of the world’s foremost advocates for persons seeking the return of assets lost during the Third Reich.

The project’s first big break came in January 2005, when the Art Loss Register contacted Epstein about a nineteenth-century work by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, called Girl from the Sabine Mountains. Off the art market for sixty-eight years, the painting of a peasant woman resting languidly by a tree had been consigned to Estates Unlimited, a small Rhode Island auction house, by Maria-Louise Bissonnette, an octogenarian German baroness who lived in Providence. On behalf of the Stern estate, the ALR’s historic claims department requested the auction house withdraw the painting from the sale, and the HCPO sent Bissonnette a letter asking her to return it to the Stern estate.

The baroness refused, claiming she had inherited the work from her mother, whose second husband, Karl Wilharm, purchased it at the 1937 Lempertz sale. Disputing—or ignoring—the fact that her stepfather was a high-ranking member of Hitler’s storm troopers, she offered his bill of sale as evidence that the work was hers. “Why should I give the painting back,” she asked, “when there is no proof that it was a forced sale? ”

With the Winterhalter auction only seventy-two hours away, the Stern estate had no time to waste. “The auction house—a small outfit—wouldn’t take our calls,” says Epstein. “We had to request an injunction to stop the sale.” Estates Unlimited returned the painting to Bissonnette, who then sent it to Germany, where she initiated a lawsuit asserting her ownership. The estate countered by taking her to court in Rhode Island on the grounds that she had exported a work of stolen property.

In December 2007, Chief US District Judge Mary Lisi ruled in favour of the plaintiffs and instructed Bissonnette to return the painting to the Stern estate. “Dr. Stern’s relinquishment of his property was anything but voluntary,” she said. In a statement submitted in support of the estate’s case, Lynn Nicholas, author of The Rape of Europa, said Stern’s surrender of the paintings “was ordered by the Nazi authorities and therefore the equivalent of an official seizure or a theft.” The decision was historic, because it recognized that the majority of German and Austrian Jews lost their artworks through Nazi coercion, acknowledging for the first time that a forced sale was in fact a theft.

Bissonnette appealed the case, and Girl from the Sabine Mountains remained in a German warehouse for another two years. It was transferred to Stern’s executors only when she lost the appeal in 2008. (Today, it is on loan to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.) Two more works from the Lempertz auction were returned a few months later. In all, the Max Stern Art Restitution Project has recovered twelve paintings, for an average of one a year.

In the two years between receiving the first notice from the Nazis and the Lempertz auction, Stern put up a vigorous fight. First he tried the courts, appealing the law that prohibited him from selling art—and buying him time, he hoped, to find someone of Aryan descent who could act as a front man while he remained “in reality the owner.” His friend Cornelis van de Wetering, an assistant to the director of the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum, agreed to help, but he was Dutch and the Nazis deemed the Galerie Stern too important to be placed in foreign hands. Next he approached Karl Koetschau, the director himself, but one of Koetschau’s great-grandparents was Jewish, which ruled him out too. At this point, Stern decided to move his business to London where, along with van de Wetering, he and his oldest sister, Hedi, opened West’s Galleries (the name a combination of Wetering and Stern).

Stern stayed behind in Düsseldorf to sell the property on the Königsallee, but by 1936 full-blown anti-Semitism had taken hold of the city. Its hospitals would no longer admit Jewish patients. Jewish officers were expelled from the army. Jewish graduate students were refused their doctoral exams. As for Stern, his clients now saw him only surreptitiously.

The situation would come to a head in the summer of 1937, when Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) opened in Munich to display works that Hitler condemned as sick and wallowing “in filth for filth’s sake.” Well-attended (and a source for the notorious Gurlitt collection), the show marked the moment at which confiscation of so-called degenerate art went public. They had been selected from the 15,997 works seized from German museums.

When Stern received notice that he had to close Galerie Stern, he realized he had no choice but to orchestrate its demise himself. The process was one that Lynn Nicholas described as “convoluted and drawn out.” The Nazis achieved their objective “of eliminating Jews and other aliens from German society while exploiting their assets and making the process appear legal.” No single document in Stern’s archives records the steps he took, but the details can be pieced together, including the choice of the Lempertz auction house. Stern was likely aware that his father had enjoyed a relationship with the firm going back to his days in München-Gladbach. The catalogue for the auction resembled Galerie Stern’s trademark style, including elegant typography and a thick white stock for the cover, a further indication, says Dombowsky, “that Max played a role in the sale.”

No one knows who attended the Galerie Stern auction. The Lempertz records were destroyed when Cologne was bombed during the war, and Stern himself was silent on the subject. But the three-day event’s size would have attracted business leaders, political officials, and museum directors—clients who had once frequented the Königsallee gallery, people who now travelled to Cologne to take advantage of what were guaranteed to be low prices on one of Düsseldorf’s most esteemed collections.

Stern’s lifelong silence on the event may be “attributed to a sense of guilt or failure,” says Catherine MacKenzie, a professor of art history at Concordia who has studied the auction extensively. “He had, after all, lost the family gallery for all time.” Years later, Stern offered only one line in a draft memoir about his participation. “When the prices did not reach the limit that I had given, I very often gave a sign to the auctioneer, which we had made out, so that he would know that I was accepting a lower offer.”

As he watched the gavel fall on Wilhelm von Schadow’s self-portrait, Stern must have thought about how the proceeds from the auction would help him build a better, new life in London. But this was not to come to pass. After he left Düsseldorf, German authorities froze his assets, and less than a year later they forced him to relinquish them in return for an exit visa for his mother. He never saw a cent from the Lempertz sale.

In November 1972, almost thirty-five years to the day after the von Schadow self-portrait went on the auction block, an undisclosed consignor sent it to Lempertz for a second time. The painting was purchased by the Stadtmuseum Düsseldorf, where it remained in relative obscurity for the next forty years. In 2009, Dombowsky discovered an image of the work in a catalogue for a 1976 Düsseldorf Museum Kunstpalast exhibition about the mid-nineteenth-century American artists who had been drawn to von Schadow’s celebrated academy (most famously Emanuel Leutze, who painted Washington Crossing the Delaware). The catalogue revealed the painting’s location to be the Stadtmuseum.

Following Dombowsky’s lead, the Max Stern Art Restitution Project approached the museum, which was unaware of the painting’s fraught past. Lempertz had passed on incomplete information about its provenance when it was acquired. The two parties discussed restitution, cautiously and at first slowly. “It was a complicated process,” says Epstein, “because Germany still has no laws outlining how to deal with claims.” By late 2013, having accepted the moral and legal arguments the project had advanced in previous claims, the museum agreed the portrait should be returned to the Stern estate. However, the painting will continue to hang in the Stadtmuseum Düsseldorf—with an acknowledgment that it is on loan.

Max Stern’s story will be a part of the portrait’s display. “A painting presented without details of its context is nonsense,” says Susanne Anna, the museum’s director. Anna negotiated with the Stern estate to keep the work on view “not because it is a great painting,” but to remind visitors that “art was only one thing stolen by the Nazis. They took everything—rugs, bicycles, cars, carpets, candlesticks, books—turning Germany into a garage sale of Jewish goods to finance the war. We know about the most famous, museum-quality objects, but not about the rest.”

Under Anna’s direction, the gallery will also organize two exhibitions around the von Schadow self-portrait: one on Jewish life in Düsseldorf, opening in 2015; the other on Stern and his collection, scheduled for 2018. As well, the museum will become a centre for education on provenance research.

Epstein believes these victories are just the beginning. “Numerous restitution cases, relating to Aboriginal war losses and other historical cases, will be exposed to the same arguments that we have brought forth,” he says. Questions of cultural ownership and art attribution are about to undergo intense rethinking. The very notion of what constitutes a museum will come under scrutiny as institutions like the Stadtmuseum Düsseldorf overhaul the process by which cultural objects are described and catalogued. Each Stern estate restitution will heighten public intolerance of the art world’s obfuscation of provenance. “We hope,” says Epstein, “that one day it will be ethically untenable to visit a museum with stolen art on its walls.”

During his lifetime, Max Stern was legally limited in retrieving what was taken from him, but the events he set in motion when he died have fired the consciences of curators, policy-makers, judges, and governments around the world. His story, no longer a secret, is bringing us closer to realizing Wilhelm von Schadow’s ideal: the truth found through art.

This appeared in the October 2014 issue.