Consternation rumbled across the country like an approaching thunderhead. For aboriginal leaders, one of their worst nightmares appeared about to come true. Two weeks before last June’s federal election, pollsters were suddenly predicting that Conservative leader Stephen Harper might pull off an upset and form the next government. What worried many in First Nations’ circles was not Harper himself, but the man poised to become the real power behind his prime ministerial throne: his national campaign director Tom Flanagan, a U.S.-born professor of political science at the University of Calgary.

Most voters had never heard of Flanagan, who has managed to elude the media while helping choreograph Harper’s shrewd, three-year consolidation of power. But among aboriginal activists, his name set off alarms. For the past three decades, Flanagan has churned out scholarly studies debunking the heroism of Metis icon Louis Riel, arguing against native land claims, and calling for an end to aboriginal rights. Those stands had already made him a controversial figure, but four years ago, his book, First Nations? Second Thoughts, sent tempers off the charts.

In it, Flanagan dismissed the continent’s First Nations as merely its “first immigrants” who trekked across the Bering Strait from Siberia, preceding the French, British et al. by a few thousand years—a rewrite which neatly eliminates any indigenous entitlement. Then, invoking the spectre of a country decimated by land claims, he argued the only sensible native policy was outright assimilation.

Aboriginal leaders were apoplectic at the thought Flanagan might have a say in their fate. Led by Phil Fontaine, National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, they released an urgent open letter demanding to know if Harper shared Flanagan’s views. Two months later, Harper still had not replied. For Clément Chartier, president of the Métis National Council, his silence speaks cautionary volumes. Martin’s minority government could fall any minute, giving Harper a second chance at the governmental brass ring. “If Flanagan continues to be part of the Conservative machinery and has the ear of a prime minister,” he worries, “it’s our existence as a people that’s at stake.”

That protest provided a wake-up call about Harper’s agenda for others too—not least among them disenchanted Tories who found themselves shut out of the election campaign. At a time when Harper remains vague about his agenda and the Conservatives’ first policy convention has been postponed, some have been stunned to discover that the party’s course may have already been set by Flanagan and a handful of like-minded ideologues from the University of Calgary’s political-science department.

Who are these men—for they are, without exception, men—in Harper’s backroom brain trust, collectively dubbed the “Calgary School”? Flanagan won his conservative spurs targeting the prevailing wisdom on the country’s native people—what he calls the “aboriginal orthodoxy.” Others like Rainer Knopff and Ted Morton—Alberta’s long-stymied senator-elect—have built careers, and a brisk consulting business, taking shots at the Charter of Rights, above all its implications for the pet peeves of social conservatives: feminism, abortion, and same-sex marriage.

But what binds the group is not only friendship, it’s a chippy outsiders’ sense of mission. In a torrent of academic treatises and no-holds-barred commentaries in the media, they have given intellectual heft to a rambunctious, Rocky Mountain brand of libertarianism that has become synonymous with Western alienation.

That neo-conservative agenda may read as if it has been lifted straight from the dusty desk drawers of Ronald Reagan: lower taxes, less federal government, and free markets unfettered by social programs such as medicare that keep citizens from being forced to pull up their own socks. But their arguments echo the local landscape, where Big Oil sets the tone—usually from a U.S. head office—and Pierre Trudeau’s 1980 National Energy Policy left the conviction that Confederation was rigged against the West.

They also share one beef not confined to Alberta: exasperation at Ottawa’s perennial hand-wringing over Quebec. In a 1990 essay in the now defunct West magazine, Barry Cooper, Flanagan’s closest departmental pal, advised Quebec separatists that if they were heading for the federal exit, they’d better get on with it—or, as he now sums it up, “The sooner those guys are out of here the better.” Cooper and David Bercuson, now director of the university’s Centre for Military and Strategic Studies, promptly followed up with Deconfederation:Canada without Quebec, a polemic that rocketed to the top of best-seller lists and sent shockwaves across the country.

Cooper’s article was entitled “Thinking the Unthinkable,” a headline that might have been slapped on most of the Calgary School’s work. Revelling in their unrepentant iconoclasm, its members take pride in airing once verboten ideas that they have helped convert to common currency in the national debate. “If we’ve done anything, we’ve provided legitimacy for what was the Western view of the country,” says Cooper, the group’s de facto spokesman. “We’ve given intelligibility and coherence to a way of looking at it that’s outside the St. Lawrence Valley mentality.”

But what has put the Calgary School on mainstream radar is not merely its academic rabble-rousing, it’s the group’s growing influence on Canadian realpolitik—first through Preston Manning, whose Reform Party tugged the ruling Liberals inexorably to the right; now through Stephen Harper, who commands the best parliamentary showing for any combination of conservatives in a decade—and sits only a vote of confidence away from toppling the government. In both cases, the linchpin has been Flanagan, once Manning’s right- hand man, who masterminded Harper’s campaign and remains his closest confidant.

Little is known about the shadowy, sixty-year- old professor who is staying on Harper’s post- election payroll as a senior advisor from Calgary. Flanagan declined to be quoted in this story. In Ottawa, where he has refused interviews for the last three years, some journalists regard him as a modern- day Rasputin manipulating a leader sixteen years his junior. But in Calgary, one of his former students, Ezra Levant, publisher of the eight-month- old Western Standard magazine, cautions against that generational cliché. These days, Levant sees Flanagan and Harper more as “symbiotic partners.” But he does not disagree with a Globe and Mail report that once referred to Flanagan as the original godfather of the city’s conservative intellectual mafia. “I call him Don Tomaso,” Levant says. “He is the master strategist, the godfather—even of Harper.”

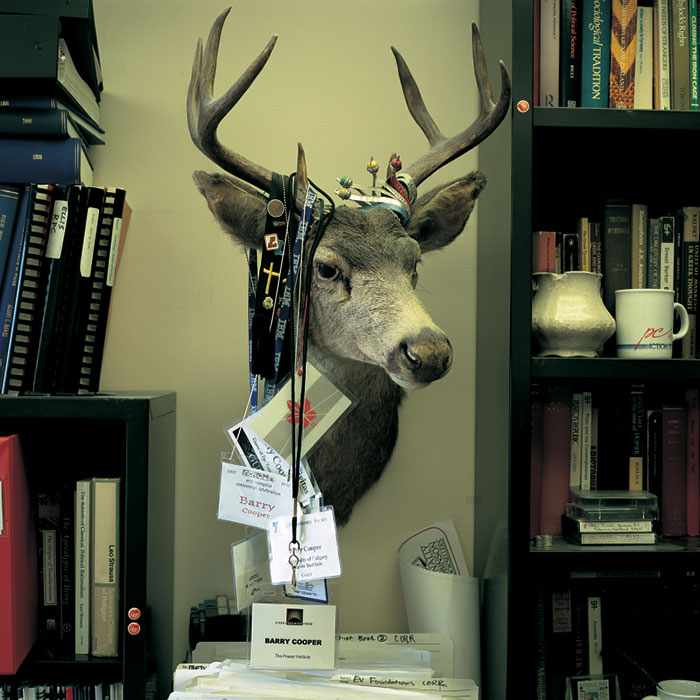

The first clue that the University of Calgary political science department is not quite like any other stares out from Room 748 of the Social Sciences tower—the book-crammed cubby-hole that serves as Barry Cooper’s office. Above a visitor’s chair hangs the mounted head of a black-tailed deer, academic conference credentials dangling from its antlers. Cooper didn’t bag the deer himself, but that doesn’t mean he would have had qualms about doing so. One of the ties that binds the members of the Calgary School is their macho derring- do in the wilds.

Cooper’s bulletin board is littered with snapshots chronicling their hunting and fishing trips. Flanagan, who declines to hunt, is an avid hiker and fisherman who for years led Cooper, Bercuson, and assorted others on an annual angling expedition to the Northwest Territories, where they flew in by Twin Otter to a cabin on Hearne Lake. As airfares soared, Flanagan decreed a change of venue. “Tom said, ‘This year we’ve got to go for meat fish,’” Cooper recalls. “Then he cancels out because of the bloody election.”

Harper himself has never been part of the Calgary School’s rollicking outdoorsmanship. But their tales provide grist for an image mill meant to set it apart from the Eastern academic establishment, which Cooper scorns for its timorous “garrison mentality.” As a disgruntled voice of the West in his weekly Calgary Herald columns, Cooper plays his own role to the hilt. He loves to recount how his great-grandmother shot an Indian intruder in her Alberta ranch house and his uncle announced the Calgary Stampede for forty-two years. He is less quick to admit that, growing up as the son of a wealthy doctor in Vancouver, he went to Shawnigan Lake School, one of the country’s more elite private boarding schools, north of Victoria.

In fact, Cooper didn’t come to U of C until 1981—the last of the group to arrive—after ten years teaching at York University, where Jack Layton was one of his students. His friends from those days can’t recall him showing any interest in politics until he moved west. “Barry’s ideas were shaped by Alberta,” says Edward Andrew, a political-science professor at the University of Toronto, who dismisses his old pal as “a poseur. Partly he just likes to be a bad boy,” Andrew says. “The only influence on Cooper was that he didn’t get a job at U of T, despite my best efforts, so he became a Western chauvinist.”

Andrew is not so indulgent about Flanagan, whose flinty reserve and dry wit often earn him the label “chilly.” Unlike Cooper or Bercuson, Flanagan appears never to have strayed from a conservative path. As he likes to point out to startled Canadians, that path began in Ottawa—Ottawa, Illinois, a blue-collar town 130 kilometres southwest of Chicago. What he seldom mentions is Ottawa’s chief claim to fame: on August 21, 1858, ten thousand people gathered in the town square to hear the state’s young senatorial candidate, Abraham Lincoln, square off against his rival Stephen Douglas in the first of their legendary debates on slavery.

Flanagan shrugs off the Lincoln-Douglas debates as meaningless in shaping his political world view—just a plaque in the park. Shirley Hiland, a fellow student at Marquette High, is not surprised. Hiland recalls that the nuns on the Roman Catholic school’s teaching staff avoided such potentially charged chapters of history. Instead, they focused on the heroic feats of the French missionary who gave the school its name: Father Jacques Marquette who teamed up with the voyageur Louis Jolliet to become the first Europeans to discover and trace the Mississippi. “The emphasis was on Father Marquette,” Hiland says, “and how he brought Catholicism to the Indians.”

In a town where almost everybody worked for Libby Owens Ford, Flanagan’s father had a white- collar job, managing the outlet of an auto -parts chain, that put the family a notch up the local social ladder. The defining influences on the household were the Roman Catholic Church and the Republican Party, two forces that did not always mix. Most U.S. Catholics then voted Democrat, but the only time Flanagan’s father made that radical gesture was in 1960 when a fellow Irish Catholic named John Kennedy ran for president.

Popular and known for taking on any teacher he thought had made a mistake, Flanagan graduated from Marquette in 1961 as class valedictorian, winning a $500 scholarship from the Retail Clerks of America—more than half his college tuition—a reward for his after-school labours at the town A & P. His father wanted him to go to Harvard, but he opted for the Catholic bastion of Indiana’s Notre Dame, where political science meant Plato, Aristotle, St. Augustine, and Thomas Aquinas.

On every side, the social glue of America was coming unstuck: Kennedy was assassinated, Martin Luther King marched on Washington, and protests against the Vietnam War were breaking out like wildfires. But at Notre Dame, Flanagan found a haven of tradition and certainty. There he met his first wife and was captivated by another figure who would shape his career: Eric Voegelin, a German-born philosopher who had fled Hitler and blamed a flawed utopian interpretation of Christianity for spawning totalitarian movements like Nazism and Communism. In Voegelin’s complex Weltanschauung, Flanagan found a philosophical framework that reconciled his Roman Catholic faith with his family’s conservative politics. He confided later that he felt he’d been drifting leftward. Suddenly, Voegelin pulled him back from that perilous course.

Flanagan went on to pursue his PhD at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, where John Hallowell, one of Voegelin’s disciples, presided over the political science department. Among his fellow grad students was an ebullient Canadian with whom he found himself sharing real estate at the campus library. “I show up in the carrel I’ve been assigned,” Cooper recalls, “and Flanagan’s in it.”

They worked out shifts—Flanagan, by then married, got the cubicle by day, Cooper at night—laying the foundations for a forty-year friendship. In 1996, at the height of Flanagan’s notoriety for Riel-bashing, Cooper thumbed his nose at his pal’s critics by nominating him to the Royal Society of Canada. “I don’t think I disagree with Tom on anything,” Cooper says. “Political or intellectual.”

In Durham, a North Carolina radio host named Jesse Helms was constantly denouncing desegration on air, cloaking his rage in the mantra of federal decentralization: states rights. But classmates can’t recall Flanagan or his Duke pals ever debating lunch-counter sit-ins or other Sixties’ hot-button issues when they met for barbecue and hush puppies on Friday nights. “I don’t remember any discussion of the civil-rights movement or the draft,” says Elliot Tepper, a Carleton professor who was Cooper’s roommate. “We were not into sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll. We were into witty exchanges of bons mots.”

The closest brush Flanagan had with the hurly burly of live politics was the friendship he struck up with one of Cooper’s professors, Allan Kornberg, Duke’s expert on decoding the statistical mysteries behind voting patterns—a science then still in its infancy. A native of Manitoba, Kornberg was celebrated on campus for financing his academic career not only as a lineman for the Winnipeg Blue Bombers, but as a professional wrestler, the “Kosher Krusher.” He was a key influence on Duke’s Canadian studies program, and since 1964 has charted the political winds in Canada, including those that swept through the last election. Now, at 73, the self-confessed “registered Republican” applauds Flanagan and Cooper’s increasing clout. “Given the left-of-centre intellectual climate in Canada,” he says, “I’m delighted. It’s good for debate.”

Kornberg has been periodically seconded to ply his expertise on Canada for the U.S. government, probing the risk of a destabilizing crack-up on America’s northern flank. Before the 1995 Quebec referendum on sovereignty, he was on loan to Washington’s National Science Foundation, constantly measuring Lucien Bouchard’s péquiste troop strength. Later, he took the pulse of Reform Party voters. Beneath the yawn-inducing titles of his studies—A Polity on the Edge: Canada and the Politics of Fragmentation—his work has surveyed the national psyche through every tremor that might send U.S. bureaucrats scrambling for a foreign-policy Plan B. Those governmental gigs are listed on Kornberg’s curriculum vitae, along with consulting stints to the U.S. State Department and the Pentagon. But in a phone interview, he adds one detail: during the Vietnam War he was “a consultant on psychological operations and counter-insurgency”—a rare intelligence assignment for a political numbers cruncher.

In 1967, Flanagan’s burgeoning friendship with Kornberg spawned his first scholarly paper: a joint study of the ultra-conservative voters who backed Barry Goldwater’s abortive 1964 bid for the White House. Even then, Kornberg regarded Flanagan as one of Duke’s most conservative students. “He believes many people want a risk-free society,” Kornberg says. “He is sort of like Goldwater: he believes people have to take care of themselves.”

What brought Flanagan to Alberta where that bootstrap ideology would find such fertile ground? He says only that he needed a job: he and his wife had already started a family (last year his oldest daughter, Melissa, retired from a twelve-year communications career with the U.S. Army). At the time, new Canadian universities were hatching across the country, prompting a hiring spree that outstripped the national crop of PhDs. But Flanagan didn’t apply for the post. In the spring of 1968, when he was offered an assistant professorship—just as Pierre Trudeau came to power—he was researching his thesis on an obscure German novelist in the turbulent compound of the Free University of West Berlin, a U.S.- funded institution briefly shuttered by anti-American protests. When the offer arrived in the mail, Flanagan had to go to the library to look up Calgary on a map.

The invitation came from E. Burke Inlow, another American, and the first head of U of C’s political-science department. An expert on Iran and the Far East who died last year, Inlow himself had been recruited directly from an assignment with the Pentagon. There, according to his son, Brand, a Calgary lawyer, he was engaged in “cultural work—providing intelligence to people we (the U.S. government) were sending to the Middle East.”

For Inlow, Flanagan’s conservative inclinations were no coincidence. He and his successors set out expressly to counter the prevailing leftist currents on the country’s campuses. “Canadian universities were almost the fiefdom of Karl Marx,” says Anthony Parel, a Jesuit-trained expert on Machiavelli, whom Inlow hired from Radio Vatican in Rome. “We wanted balance.” Balance is always in the eye of the beholder. Soon critics charged that the department had leaned too far to starboard. “They said we were all right-wing reactionaries,” Parel winces. “Very offensive epithets were used.” Radha Jhappan, now an associate professor at Carleton, remembers concluding it was pointless to apply for a more senior post in what she now refers to as the “department of redneckology.” At U of C, “I realized they’d rather hire a chimpanzee than me,” she says. “I was perceived as leftist, feminist—everything they can’t abide.”

Still, it wasn’t until the spring of 1996 that Flanagan bounded into the department brandishing a paper from a scholar at Johns Hopkins’ School of Advanced International Studies in Washington. “He said, ‘Hey guys, guess what? We’re a ‘school!’ ” Cooper recalls. That twenty-page treatise entitled “The Calgary School: The New Motor of Canadian Political Thought” reported that a band of Alberta academics had “given birth to a new form of nationalism, that in turn is changing the terms of debate in English Canada.”

Today, its members can’t seem to decide whether to bask in their ongoing celebrity or shoot down the notion entirely. “It’s an external construct,” scoffs Cooper, rhyming off the group’s internal differences, then diving into his filing cabinet to unearth proof of their shared crusades. But it seems no accident that the group’s first nod of recognition came from an American. Not only are Flanagan and Morton U.S.-born, but Cooper is a member of the Bohemian Club, a fraternity of Republican movers and shakers who fork out a $10,000 initiation fee to gather every year in the redwoods outside San Francisco for a policy version of summer camp. In a crowd that has included Henry Kissinger and Vice-President Dick Cheney, Cooper gives a regular talk on Canadian politics—one reason the Calgary School’s views may hold more sway in Washington than Ottawa.

For the Calgary School, in turn, intellectual inspiration has always run north-south, not east-west. Its papers are studded with admiring references to some of the most controversial figures on the U.S. conservative landscape. In his argument for aboriginal assimilation, Flanagan repeatedly cites Thomas Sowell, a black Republican who became the darling of the Reagan-Bush right for attacking affirmative action. Not surprisingly, most of the group’s policy prescriptions—from an elected senate to parliamentary approval of judges—would have one effect: they would wipe out the quirky bilateral differences that are stumbling blocks to seamless integration with the United States.

But Shadia Drury, a member of the U of C department until last year, accuses her former colleagues of harbouring a more sinister mission. An expert on Leo Strauss, the philosophical father of the neo – conservative movement, Drury paints the Calgary School as a homegrown variation on American Straussians like Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz, who share their teacher’s deep suspicions of liberal democracy. Strauss argued that a ruling elite often had to resort to deception—a noble lie—to protect citizens from themselves. To that end, he recommended harnessing the simplistic platitudes of populism to galvanize mass support for measures that would in fact restrict rights. Drury warned the Globe’s John Ibbitson that the members of the Calgary School “want to replace the rule of law with the populism of the majority,” and labelled Stephen Harper “their product.”

If so, there’s no mystery in the appeal of Strauss’s theories to Flanagan or Cooper, who edited Strauss’s thirty-year correspondence with Voegelin, Faith and Political Philosophy. “Strauss believed that good statesmen have powers of judgment and must rely on an inner circle,” the University of Chicago’s Robert Pippin told Seymour Hersh in the New Yorker last year. “The person who whispers in the ear of the King is more important than the King.”

From his summer home outside Washington, Kornberg scoffs at charges that his protegés are ultra-rightists masquerading as anti-establishment eggheads. “Their extremism has been greatly exaggerated,” he says. “It wouldn’t be surprising if it came from the University of Toronto or McGill. It’s the fact that it’s a provincial university out West that people find outrageous—how dare they?!”

At first, Flanagan had no plans to stay in Calgary. His wife was homesick—she eventually left the country, and the marriage, with their two kids—and he’d never had the slightest interest in Canadian politics. But once he decided to apply for citizenship, he volunteered to teach a summer class in the subject to force himself into a crash course. In the midst of that reading blitz, he stumbled on Louis Riel, the Metis firebrand hanged by Sir John A. Macdonald’s government in 1885 for treason.

What intrigued Flanagan was not Riel’s contentious place in history, but scattered references to his claims of prophecy. For Flanagan those allusions were the equivalent of a scholarly smoking gun. Suddenly, he saw Riel’s Metis rebellions as an attempt to found one of those misguided messianic movements against which Voegelin had warned. In Riel’s diaries and the obscure archives of Roman Catholic orders, he found evidence of his suspicions.

The result was Louis “David” Riel: Prophet of the New World, his 1979 profile of a man driven by ecstatic visions to raise a purified North American version of the Catholic Church with its papal seat in St. Boniface outside Winnipeg. According to Flanagan, not only did Riel view himself as its chief prophet—an heir to the Biblical King David—but he went to the gallows convinced that, Christ-like, he would rise again on the third day. “Riel did not see himself as a tribal soothsayer,” Flanagan writes. “He was the voice of God to a sinful world.”

Historians applauded Flanagan’s research, excavating Riel’s unsuspected religiosity, and the University of British Columbia awarded him its biography prize. But Metis and aboriginal scholars were appalled. Flanagan’s Riel wasn’t merely a stressed-out leader who’d had a mental meltdown; he was a delusional religious crackpot. “He turns nearly every interpretation of Riel into megalomania,” says Regina writer Maggie Siggins whose best-selling biography of Riel appeared five years later. “To make him that kind of crazy is to say that aboriginal people who followed him have no claim on land.”

It would take Flanagan another four years to get around to the subject of land claims. Along the way he became a one-man Riel industry, turning out a flood of books and papers, then constantly updating them with new research that spurred him to increasingly damning conclusions. In his 1983 preface to Riel and the Rebellion: 1885 Reconsidered, Flanagan confessed that earlier he’d taken for granted that the Metis had justified gripes. Now he was recanting. “I concluded that… the Metis grievances were at least partly of their own making,” he wrote. Flanagan admitted he was rushing his revised opinions into print with a motive: to block lobbying for a posthumous pardon that would exonerate Riel in time for the 1985 centennial of the Northwest Rebellion. A pardon, he declared, “now strikes me as quite wrong.”

By the 2000 edition, he was even more adamant. Rehabilitating Riel’s reputation, he warned, could cost Canadian taxpayers billions in Metis land claims. What seems most striking about the revised text is its notched-up adversarial tone. Flanagan’s closing argument reads not like a measured scholarly assessment, but political scare-mongering. In establishing his Metis provisional governments, Riel had twice issued unilateral declarations of independence from the federal government, Flanagan pointed out—exactly what Ottawa feared from Quebec.

What had happened to provoke not only Flanagan’s hardened line, but his rush to man the federal barricades? He has said he simply had a chance for more research—an exercise that turns out to have been financed largely from federal coffers. Between 1972 and 1994, he received nearly $620,000 in research grants on the subject from the Canada Council and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. That largesse includes a rare scholarly bonanza: $500,000 for a five-year project with four other academics, co-editing the collected writings of Louis Riel.

But Flanagan’s views wouldn’t have raised more than eyebrows if his telephone hadn’t rung on a June afternoon in 1986. The Justice Department offered him a $103,000 contract as its chief historical consultant on one of the biggest land-claims cases before the federal courts: a suit by the Manitoba Métis Federation for 1.4 million acres promised to Riel and his followers in 1870.

Flanagan has gone on to reprise that role in a half-dozen other federal aboriginal disputes, including Victor Buffalo, et al. vs.The Queen—a landmark claim for more than $1 billion in damages by the Samson Cree Nation at Hobbema, near Edmonton, over Ottawa’s handling of its oil and gas royalties. The Manitoba and Alberta governments have also hired him for their own battles over treaty rights. “What he’s become is a very convenient tool for the government,” says David Chartrand, president of the Manitoba Métis Federation.

Flanagan’s expert-witness stints have not proved unrewarding, but friends insist he is driven not by money but ideology. “He’s concerned the state should not adopt people as wards,” says Allan Kornberg. “It eventually has a corrosive effect on the entire society.” That libertarian loathing of special rights for any group is the philosophical underpinning of Flanagan’s most provocative work, First Nations? Second Thoughts, which unleashed outrage not only in aboriginal circles, but in the usually restrained corridors of academe. “These aren’t second thoughts,” says Joyce Green, an associate professor at the University of Regina and a Metis herself. “They’re the same old first thoughts that the colonizers came with from Europe. It’s a celebration of the original arguments that supported the subordination of indigenous peoples.”

What ignited the most fury was Flanagan’s contention that aboriginals were simply conquered peoples who’d been bested by Europeans with a higher degree of “civilization,” as he termed it. That argument, peppered with references to “savagery,” hadn’t been heard in polite company for decades. “There’s a fundamental racism that underpins his view,” says Radha Jhappan. “It’s an amazingly selective reading of history and it’s driven by a particular right-wing agenda that wants to undermine the claims of collectivity.”

But Flanagan’s fans cheered the book as a brash intellectual ice breaker on a subject that has bedevilled Ottawa policy-makers for years. “What Tom was trying to do was demythologize a lot of stuff that needed demythologizing,” says David Bercuson. “Political correctness had settled over the issue like a wet blanket.”

When First Nations? Second Thoughts won the $25,000 Donner Prize in 2001, Flanagan’s foes weren’t surprised. The award is funded by the Donner Canadian Foundation, which set out to promote a Reaganite agenda in this country. The foundation, in fact, funded Flanagan’s basic research with a $25,000 grant.

But when the Canadian Political Science Association (cpsa) awarded Flanagan’s book its prestigious Donald Smiley Prize, all hell broke loose. Gurston Dacks, an expert in aboriginal rights who chaired the three-member jury, quit after finding himself outvoted. In a tense, closed-door session, the cpsa’s board decided to keep Dacks’s walkout under wraps and even today no one will talk about it. But in political-science circles the decision left lasting bruises. “It fractured the community,” says Joyce Green, “because it implicated us all in rewarding something that many of us felt was deeply wrong.”

Today, Flanagan’s work remains an explosive topic, but few of his colleagues are willing to criticize him—at least on the record. After an introductory political-science textbook he co -authored was dropped from Ontario’s approved list of high-school texts because of its “racial, religious, and sex bias” against women and Jews, he became active in the Society for Academic Freedom and Scholarship, an aggressive lobby of professors fighting political correctness, on whose board he now sits.

Certainly, by last June there was no lack of opinion that Flanagan’s own writings were controversial, if not right off the mainstream map. As the Conservatives’ campaign director, he seemed perfect fodder for the sort of Liberal attack ads already depicting Stephen Harper as a scary extremist with a hidden agenda. The mystery is why Paul Martin’s admen didn’t jump on that tailor-made target.

One reason for their reluctance may well have been case #C1- 81- 01- 01010. After twenty years, the Manitoba Metis’ land claims are still in federal court and the stakes for Martin’s government are high—vast tracts of prime Manitoba real estate, including slices of Winnipeg, and cash reparations that could run to billions of dollars. In that battle, as in at least two others, the Department of Justice is still pinning much of its defence on Flanagan’s expert testimony.

The Liberals’ silence not only left him untouchable, but it may have allowed Harper to sidestep the question posed by aboriginal leaders: does he share Flanagan’s views? Rick Anderson, who has worked with both Harper and Flanagan in the Reform Party, has no doubts. “I’d be astounded if it were otherwise,” he says. “They’re intellectual soulmates, philosophical soulmates.”

Journalist Lorne Gunter (left) and Tom Flanagan (right) showed a united front in catching the same fish. This explanation is courtesy of Mr. Flanagan:

“The picture comes from a fishing trip about three years ago, to Gordon Lake in the NWT. On the trip were David Bercusson, Barry Cooper, Lorne Gunter, and me. David, Barry, and I had been going on these trips for years, but it was Lorne’s first time (he is now a regular). Lorne had done almost no fishing in his life. I took him with me the first morning and showed him how to set up the tackle, bait the hook, etc. He was trolling while I drove the boat. We’d been fishing less than an hour when he got a strike and finally landed the 36-pound lake trout you see in the picture. I netted the fish, took the hook out, and with Lorne’s camera snapped a picture of him holding the fish. I’ve been fishing all my life and had never even seen a fish like that. Lorne goes fishing and catches a monster the first time, in less than an hour. You may well ask, Where is the Just Society? Anyway, I consider it partly ‘my’ fish because of the contributions described above. After Lorne sent me the picture, I had a friend take a shot of me with her digital camera and scan my head onto Lorne’s body. That’s why I look so relaxed, because I wasn’t actually holding a slippery 36-pound fish! I’d love to simply publish the picture and thus complete my campaign of historical revisionism. But in fairness to Lorne, we have to ask his permission and promise to put in some kind of explanation.”

In a cramped, windowless office at Calgary’s Canada West Foundation, Preston Manning tries to keep his eye on the big picture. Down the hall in a glass-walled corner suite, the foundation’s president, Roger Gibbins, had just vented his post-election spleen in a Globe opinion piece, blasting Paul Martin’s campaign rhetoric for stoking Western alienation. That tirade hardly seems unexpected from a think-tank long regarded as an arm of Manning’s defunct Reform Party, but in his own commentaries, Manning, the foundation’s star fellow, strikes a more conciliatory note. He is careful never to betray bitterness toward the two protegés who helped orchestrate his ouster from the movement he founded—Stephen Harper and Tom Flanagan—both once his closest aides. “These politicians who keep score,” Manning says, “it’s just a waste of energy. Now if you talk to my wife you might get a different story.”

For nearly two decades, Manning had dreamed of launching a Western-based populist movement that took up where his father’s Bible-thumping Social Credit Party had left off. In 1987, with Westerners furious at Brian Mulroney’s gst and mollycoddling of Quebec, he sensed the time was ripe. A policy wonk who’d worked on systems theory for a U.S. defence contractor during the Vietnam War, Manning asked Gibbins—then head of U of C’s political science department—to pull together some intellectual wattage to help hammer out a platform.

During those brainstorming sessions in the departmental conference room, Flanagan and his colleagues not only met Manning, but the grave young grad student who was already his policy chief. Harper was just finishing his Master’s degree with Robert Mansell, a neo-conservative economics professor who joined the group, but Gibbins can’t remember Harper uttering a word. “He had a quiet, very serious, imposing presence,” recalls Radha Jhappan. “I got the feeling he was one of the people pulling Manning’s strings—definitely playing an influential role.”

For Manning, the relationship with Harper was “very much an intellectual one. Stephen was one of the few people who could write speeches for me with very few changes,” he says. Not that Harper had any knack for Manning’s trademark folksy phraseology. “Stephen’s preferred method of communication is policy-writer language,” he says. The down-home parables that Manning added came from cocking a careful ear to the small talk after political meetings—part of the process he calls “democratic discourse.” Harper had no time for it, then or later. “Stephen worried about the dark side of populism,” Manning says. “He’d feel I went overboard on all this grassroots stuff.”

In October, 1987, when Manning launched the party in Winnipeg with the rallying cry, “The West Wants In,” its policy manifesto may have been Harper’s handiwork, but the Calgary School could see its own fingerprints on the pages of that Blue Book. Still, once Reform got rolling, Manning’s ideafests at the university petered out. “We’d filled a vacuum,” Gibbins explains.

No one in the department joined the party. By then, Flanagan had plunged into a new intellectual passion, the theories of the once scorned Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek, who lauded free markets as the cornerstone of free societies, impervious to intrusive government meddling. In the late 1970s when Flanagan stumbled on his work, Margaret Thatcher had just cut short a Conservative policy confab in Britain by slapping down Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty on a desk. “This,” she said, “is what we believe.”

In the 1988 election on free trade, Flanagan cast his ballot for Mulroney’s Conservatives. He points out that even his second wife, Marianne, a speech therapist he’d met on a winter trek with the Rocky Mountain Ramblers, voted Reform before he did. But by 1990, he was furious at Mulroney’s mushrooming deficits—heresy to fiscal conservatives like himself—and he signed up. Months later, when Manning was looking for a right-hand man, Flanagan leaped at the job.

His university colleagues were stunned he was willing to rub shoulders with the Reform hoi polloi. “He is not a social animal in any way,” Gibbins says. “If people look on Harper as reserved, Tom is a further evolutionary step behind that.” At Duke, however, Allan Kornberg viewed the move as a logical leap for the grad student who’d once pored over Goldwater voting patterns. “Tom’s always been interested in building a conservative movement,” Kornberg says, “and a conservative party.”

Still, it was the theoretical nuts and bolts of politics that fascinated Flanagan—the sort of statistical prowess he’d acquired at Duke that now allows him to parse pollsters’ bafflegab. “He’d equipped himself with all this theory,” recalls Rick Anderson. “But he didn’t have much respect for the practical school of politics. And there’s no book learnin’ for that.”

For Manning, the heart of his populist vision was a constant consultation process with the party’s grassroots. Flanagan didn’t hide his distaste for it. He arrived at constituency meetings armed with studies and stats as if he were back in the classroom. “Tom would get in all these terrible tussles with folks who he thought didn’t know as much as he did,” recalls one former Reform insider. “Finally one night he just had this outburst: why are you people always talking and not listening to me? This guy goes up to the microphone and says, ‘Because we pay your salary.’ ”

In Manning’s office, Flanagan set out to create a chain of command in which everyone, including Harper, reported to him—a foretaste of the tight Conservative campaign ship he would run last spring. Along the way, he found himself stickhandling reports that security squads at some party rallies were members of the neo -Nazi Heritage Front. That scandal was sparked by the revelation that Heritage Front member Grant Bristow was a Canadian Security Intelligence Services (csis) informer. “Preston used to say, ‘When you turn on a lightbulb, you get a lot of bugs,’” Cooper says. “Well, one of Tom’s jobs was to swat the bugs.”

The party’s unruly rank and file wasn’t Flanagan’s only frustration. Manning was ignoring his flow charts and increasingly giving his counsel the cold shoulder. He felt useless, shut out of the inner circle he had tried to command. “Nobody seemed to want his advice,” Cooper says.

Manning’s closest collaborator had suddenly become Anderson, a veteran Ottawa operative who’d run the Washington office of the lobbying giant, Hill & Knowlton. To Flanagan, Anderson was a hired political gun—a onetime Liberal with no loyalty to Reform policies—who had slyly insinuated himself into the leader’s confidence. Harper too was miffed that Anderson had usurped his wunderkind role. As Manning noted later in his memoir Think Big : “Stephen had difficulty accepting that there might be a few other people (not many, perhaps, but a few) who were as smart as he was with respect to policy and strategy.”

Harper and Flanagan had already hit it off as ardent devotees of Hayek, and tolerated Manning’s populism as a tedious inconvenience. Now they were galvanized by a common foe. Their friendship was cemented in that summer of their mutual discontent. “Tom thinks along the same lines as Stephen,” Manning says. “They reinforce each other. But Tom always saw the gloomy side.”

Months before his contract ran out in the fall of 1992, Flanagan quit, blaming Manning’s decision to name Anderson manager of the next election campaign. Not only did Anderson personally disagree with one of Reform’s key platform planks—opposition to the Charlottetown constitutional accords—he had a conflict of interest: his firm, Hill & Knowlton, was the government’s lobbyist for the referendum on the subject. For Flanagan, Anderson’s views were a fireable offence. “Tom doesn’t like the kind of hypocrisy you need in politics,” says John Herd Thompson, former head of Duke’s Canadian Studies Program. “Something’s right or wrong: he’s pretty unrevised and unrepentant.”

So anguished was Harper over whether to follow suit and abandon the Calgary Reform nomination he’d sewn up that he huddled with Flanagan and his university colleagues over his future. In the end, he went on to ride the wave that catapulted Reform from a single seat to fifty-two overnight, shattering the Conservative party into a two-seat curiosity. But Harper refused to campaign nationally and nearly a year later, when press leaks revealed an internal party probe into Manning’s expense accounts, some Reformers fingered him as the source. He promptly went public—a stab Sandra Manning never forgave. In 1997, Harper decamped to the National Citizens’ Coalition, the country’s oldest libertarian lobby, whose motto is “More freedom through less government.”

For Harper and Flanagan, Manning’s decision to appoint Anderson had symbolized his willingness to betray a fundamental Reform credo—no special rights for any group or province—in his quest for more parliamentary seats. But Manning and Anderson saw it simply as a clash of egos over who had the moxie to make the party a national force. “They tried to turn it into this whole thing about how Preston was watering down the wine,” Anderson says. “I think they were actually trying to assert who was alpha male.”

That metaphor would soon prove apt. As the long unite-the-right minuet kicked off, Flanagan and Harper began jostling for position in a dance that might have been borrowed from a text on Flanagan’s newest enthusiasm: bio-politics—a collection of controversial theories on the biological basis for power that had become the rage of the American right.

“Tom just fell in love with that literature,” Gibbins recalls, “and brought it into the classroom.” Indeed, on Flanagan’s reading list was one book that had sparked a personal epiphany: Frans de Waal’s Chimpanzee Politics, which won raves from Newt Gingrich in The New York Times. A study of the world’s largest captive chimp colony at a Netherlands zoo, it chronicles the scheming, coups, and ultimate murder of the would-be alpha male, Liut. Ezra Levant, then still a student, remembers being riveted by Flanagan’s lectures on the subject. “It was the most radical class I ever took,” he says. “If a series of young males were fighting for power, a thoughtful chimpanzee would make alliances with all the losers and eventually take over the group.”

Flanagan pressed copies of Chimpanzee Politics on Cooper and his Calgary School confreres, who delighted in watching staff meetings for tell-tale signs of simian rituals—their favourite a trademark show of bluster that de Waal dubbed “pant-hoot.” “We’d look at each other: ‘Yeah, there it is—pant-hoot,’ ” Cooper recalls.

Chimp behaviour convinced Flanagan he’d been too rigid in his first foray into the political arena. In de Waal’s Dutch colony, savvy chimps built coalitions and bided their time. Over the next years, Flanagan and Harper might not have been on Reform’s main stage, but they were far from inactive. A new intellectual infrastructure was taking shape on the Canadian right, echoing the web of conservative foundations and think tanks that paved the way for Reagan’s 1980 ascension to the White House. Flanagan became an activist in Civitas, a network of 300 conservative thinkers spawned by the 1996 Winds of Change conference that Levant and fellow National Post columnist David Frum had organized in Calgary. Toronto’s C.D. Howe Institute—whose researcher, Ken Boessenkool, would later become Harper’s policy chief—and Vancouver’s Fraser Institute, which opened a Calgary office under Cooper, were routinely proffering policies once considered too radically right wing for mainstream consumption.

In 1997, Flanagan and Harper made their media debut in the short-lived Next City, arguing coalitions were the only route to conservatives seizing national power. One combo they proposed might make compelling bedtime reading now for Paul Martin: an alliance with the Bloc Québécois, whose core rural Quebec voters “would not be out of place in Red Deer,” they noted. “They are nationalist for much the same reason that Albertans are populist—they care about their local identity… and they see the federal government as a threat to their way of life.”

Flanagan and Harper’s writing collaboration would last four years. Flanagan was the chief wordmeister, spinning out a snappy first draft at one sitting, then handing it over to Harper to refine. As Flanagan explained later, his verbal wizardry allowed Harper to get his thoughts into the media more quickly—and with more pizzazz.

Meanwhile—perhaps not coincidentally—the drum rolls of disenchantment with Manning were building. His image might no longer be a problem—Sandra Manning had shelled out for his laser eye surgery and he’d thrown away the glasses and Brylcream—but there were mounting questions about his appeal outside the West. No sooner had Manning tried another kind of makeover, rebranding Reform as the Canadian Alliance, than Flanagan painted him with the same brush that had once tarred Riel. Manning was imbued with a quasi-religious “mission” to unite the right, Flanagan told a Globe reporter, and seemed to be saying, ‘This is the manifestation of God’s will.’”

Two months later, when Manning agreed to what he regarded as a pro forma leadership race for the new party, Flanagan promptly announced he was putting his money on another horse: Alberta Treasurer Stockwell Day, who had introduced a flat tax. Day went on to win, leaving Manning’s national dream in shreds. But Flanagan’s infatuation with the new leader proved short-lived. Within a year, Day had become a national joke, mired in scandal and immortalized in comic monologues as an evangelical airhead in a wetsuit. “You’d have to be a moron,” Flanagan told Ted Byfield’s Alberta Report magazine, “not to see that the chances of the Alliance winning soon are not very great.”

In fact, Flanagan—a man now known for his aversion to the media—proved decidedly verbose on the subject of Day’s shortcomings. So busy did he seem leaking news of the tribal revolts within Alliance ranks that Rick Anderson wondered publicly “what Prof. Flanagan is trying to achieve.” In September, 2001, the answer became clear. As Day was forced to call a leadership review, a website suddenly appeared: www.draftharper.com. Flanagan turned out to be national co-chair of the movement to woo his co-author back into the political limelight.

The first clue to that scheme had surfaced nearly a year earlier. In one of their last joint literary efforts, Flanagan and Harper co -authored a public missive to Alberta premier Ralph Klein—co – signed by Boessenkool and two other members of the Calgary School—calling on him to build a political “firewall” around Alberta. That firewall letter, as it became known, demanded Klein use the muscle of Alberta’s oil wealth to sieze control over health care, opt out of the Canada Pension Plan, and send the rcmp packing in what would amount to quasi- secession from the federal bosom.

At the time, Ted Byfield thought he saw a plot: the group was positioning Harper to take on Klein in the provincial arena. In fact, their aim was more ideologically ambitious. Alberta was to be a test case in their push to untie the Big Government bonds that knit Confederation. It was only when Day’s leadership imploded that Harper and Flanagan shifted their attention back to the national stage and another means to that libertarian end.

In Harper, Flanagan finally had his dream candidate to carry the neo-conservative torch: an alter ego whose benign boyish good looks belied the radical agenda they shared. Says Cooper: “Tom understands that Stephen is a guy who has the capability of changing what the country looks like.”

Flanagan took a leave of absence to join the three-year campaign that began with Harper’s takeover of the Canadian Alliance and ended with his annexation of Peter MacKay’s Tories and his ultimate face-off against Martin last June. Some friends were astonished Flanagan opted for a role as Harper’s chief of staff, not one that would tap the sort of risk-calculating he’d honed in his 1998 text, Game Theory and Canadian Politics. But in fact Flanagan and Harper had already spent years together pondering every possible policy and tactic. “Stephen has an incredible strategic sense,” Cooper says. “It’s like playing chess: he can always see five or six moves ahead.”

On Sunday, December 7, Jean-Pierre Kingsley, Canada’s Chief Electoral Officer, went to the office. He almost never worked weekends, but Harper and Progressive Conservative leader Peter MacKay persuaded Kingsley they couldn’t wait to register their new Conservative Party of Canada, forged from a merger that had been ratified by MacKay’s members in a vote only the night before.

Already, challengers were poised to block their pact. A month earlier, after they had unveiled their deal, David Orchard, the Saskatchewan farmer whose support had clinched the Tory leadership for MacKay—and with whom MacKay had signed a written agreement not to embark on merger talks—had filed a suit to block the union. Former Tory MP Sinclair Stevens had also threatened to contest the new party’s legality—which he later did in a separate lawsuit. By rushing to register their offspring on Sunday, Harper and MacKay hoped to circumvent any process servers who might try to stop the official baptism the next business day.

MacKay makes no apology for their move. “There wasn’t any dark conspiracy,” he says. “We had ratification from our memberships that was over 90 percent.”

Orchard denounced the new party as “conceived in betrayal and born in deception.” He was not alone in his feelings of unease. For many, its furtive beginnings were a bellwether of the secretive climate that promptly descended over the Conservative election campaign. From the first, the merger was billed as a marriage of equals, and in star turns for the camera, MacKay, the deputy leader, was invariably caught in Hallmark moments of unity, applauding wildly just over Harper’s left shoulder. But behind that sunny façade of team spirit, a different reality has been unfolding. According to well-placed sources, MacKay was shut out of the party’s inner circle and given virtually no role in the election campaign.

MacKay himself refuses to confirm those leaks from angry former Tories. But according to associates, he was never included in strategy sessions or dispatched to help out other former Tory candidates, many of whom later lost. More than once when he agreed to answer a call for help, Harper’s headquarters vetoed the trip. When MacKay did come to the rescue of friends in ridings across the country it was at his own initiative. Otherwise, Harper’s official Number Two was left to sit out the race in Nova Scotia. “There were weeks at a time when Peter didn’t talk to Harper,” says an associate, “or hear from anybody in headquarters.”

Nor was MacKay the only former Progressive Conservative who found himself snubbed. Key players in the old Tory election apparatus—including the Ontario team that propelled Mike Harris to power—never received the expected calls for their services.

Some try to explain away those lapses as the pitfalls of a rough-and-tumble national race for which Harper’s team had little time to prepare. But off the record, they pin the rap on Flanagan, the supreme cog in his campaign machine. From a war room that ironically once housed Groupe Action, the ad firm behind the Liberals’ sponsorship scandal, he directed an election effort that stunned even veteran Parliament Hill reporters with its fortress mentality. “Everything was very tightly held,” says one Tory. “It was circle the wagons completely.”

At the centre, the lanky, taciturn wagon master remained a phantom presence, whose aides scrupulously referred to him as “Dr. Flanagan” but whom only a few ever glimpsed. Says a miffed Tory MP: “He was just this overlord nobody ever saw.”

Now, both former Alliance and Tory loyalists blame Flanagan for a parliamentary showing that, however strong, fell far short of the campaign’s overhyped eleventh-hour expectations. “He caused us to lose,” says an irate MacKay loyalist. “I don’t think he really understands this country.” Even some in Harper’s own ranks are equally blunt: “You can’t build an organization by excluding people,” says a former Alliance MP. “There’s a lot of bitterness out there.”

Veterans of the Reform Party see that snub of the Tories as a rerun of Harper’s treatment of party stalwarts, including his former boss Deborah Grey, who bolted the Alliance caucus under Stockwell Day. Even after Harper took over, they found themselves treated as not quite trustworthy and relegated to the back benches. As official co-chair of the Conservative campaign, Grey refuses to badmouth Flanagan—at least not in so many words. “He’s bright and he’s capable—a university guy—and I wish him well with his classes,” she says. “Some guys fit and some guys don’t.”

Critics blamed the Conservatives’ near miss on their mushy platform, but there seems no doubt the party’s policies were left purposely vague. They were released on a Saturday, under the media radar, and couched in language that the University of Lethbridge’s Geoffrey Hale calls “a masterful exercise in ambiguity.”

Now Harper and Flanagan seem in no rush to convert that cotton wool to concrete. They have postponed the party’s policy convention, originally scheduled for October, until at least March—delaying a high-risk day of reckoning that many predict could be bloody. “There will be tremendous pressure to move to the centre,” says David Taras of U of C’s Faculty of Communications and Culture. “When there’s actually a policy convention, you’ll see real struggle. It’ll be a contest for power.”

On one side are MacKay and other former Tories pressing for progressive policies—an adjective that gives neo-conservatives palpitations. “It has to happen,” MacKay insists. “This party has to portray a modern, moderate vision with compassion for people who represent all facets of this country.” For him, it’s not a matter of choice. “We’re right at the precipice of electing a new government if we play our cards right,” he says. “But we have to lead people to a new comfort zone. We don’t want to remain in opposition forever.”

Lined up against him are those true believers who have long made up the Reform and Alliance faithful—not to mention Flanagan himself. He has never blanched at owning up to his most contentious beliefs: scrapping medicare in favour of personal medical savings accounts—a policy adopted by some U.S. corporations—and whittling aboriginal claims on land and self-determination down to individual property rights and municipal self-government. Flanagan may, in fact, not be unlike Louis Riel: a man with a mission, albeit secular. In his last literary outing with Harper, a June, 2001, column in the National Post, they warned fellow conservatives to stick to their policy guns and offer a genuine right-wing alternative—not some pale vote-getting pap. “If all we want is the exercise of power,” they wrote, “we might as well join the Liberals.”

The looming power struggle is not only for the soul of the new party. It is also over Stephen Harper’s political future: how much is he willing to water down the ecumenical wine required to win the pmo? Rick Anderson calls it “the defining question of his leadership—whether he’ll fudge the party’s policies or not.”

But back in Alberta, Ted Byfield, the unabashed voice of the West since the Calgary School’s professors were pups, sees it another way—in terms Leo Strauss might have approved. “All these positions which Harper cherishes are there because of a group of people in Calgary—Flanagan most prominent among them,” Byfield says. “I don’t think he knows how to compromise. It’s not in his genes. The issue now is: how do we fool the world into thinking we’re moving to the left when we’re not? ”

To those who are unnerved by that prospect, Byfield offers no cheer. “Those people who said they’re dangerous—they’re right!” he says. “People with ideas are dangerous. If Harper gets elected, he’ll make a helluva change in this country.”