On October 27, 1995, tens of thousands of Canadians marched in Montreal against Quebec independence. Held three days before the referendum, the Unity Rally gave the final push of support for the “non” campaign. Mark Leiren-Young wrote this account of his experience at the event shortly after non won.

“All those Canadians (who went to the rallies) can look at their children and say to them the next time the Canadian flag flies, they own a piece of it. They made a difference.”

—Jean Charest, leader of the Progressive Conservatives

Even before the bilingual boarding announcement for my flight to the Unity Rally I was reminded that Canada is indeed a distinct society. To my left, a greying, grey male businessman with a French-Canadian accent was debating constitutional reform with an elderly Anglo couple. The Anglo man was a first-generation Canadian, his wife was tenth generation, and they were agreeing with their new acquaintance that even if Quebec votes to remain in Canada, the country will need to change. To my right, a couple of Anglo males in their mid-thirties were discussing the merits of René Lévesque’s approach to sovereignty.

If this isn’t distinct, what is? Where else in the world do people without political science degrees or dull government jobs willingly debate the merits of asymmetrical federalism?

Looking around the departure lounge at Vancouver International Airport I started playing spot the patriot. How many of us were heading out to Quebec in a quixotic attempt to show the people of that province that despite what they may have heard, we really care about what they decide?

As I got in line to board the plane to Toronto, from which I would transfer to a flight to Montreal, I discovered Vancouver Playhouse general manager Chris Wooten right behind me. “Why are you going to Toronto? ” I asked.

“To say no,” said Wooten, who was bringing his son and daughter along to do the same.

As we discussed our spur-of-the-moment, completely illogical decision to fly to Montreal, a middle-aged woman near us piped up “that sounds familiar.”

“So you’re going too? ” I asked.

“Absolutely,” she replied with more than a hint of pride in her voice.

Once on board I asked the woman seated beside me, Catherine McLellan, if she was off to Toronto or Montreal. “Montreal,” she replied, “to say no.” The woman in front of us turned around to announce that she too was off to the rally. The businessman behind us interrupted to ask how much was the special fare. I told him $199.50 plus tax and he declared it was “a great deal.”

The trans-Canada quest to Montreal was sparked by fisheries minister Brian Tobin, who suggested that people from “the rest of Canada” should attend a “non” rally to show that they care about the people of Quebec. It was a lovely idea if you lived in New Brunswick or Ontario, but what turned the rally into an unprecedented display of Canadian patriotism was the decision by Canadian Airlines to cut the cost of their flights to Quebec to enable people from across the country to attend. The move prompted Air Canada to follow suit, matching the fare of $99.50 for anyone within 800 kilometres and $199.50 for everyone else.

McClellan told me she was born and raised in Montreal. She was fluently bilingual, had left the city three years earlier, and said it broke her heart that she was not allowed to vote—but at least the rally would give her the chance to do something. “I had to go,” she said in the same determined tones I would hear dozens of times over the next thirty-six hours. Before leaving Vancouver, she bought a BC provincial flag so people would know how far she’d travelled.

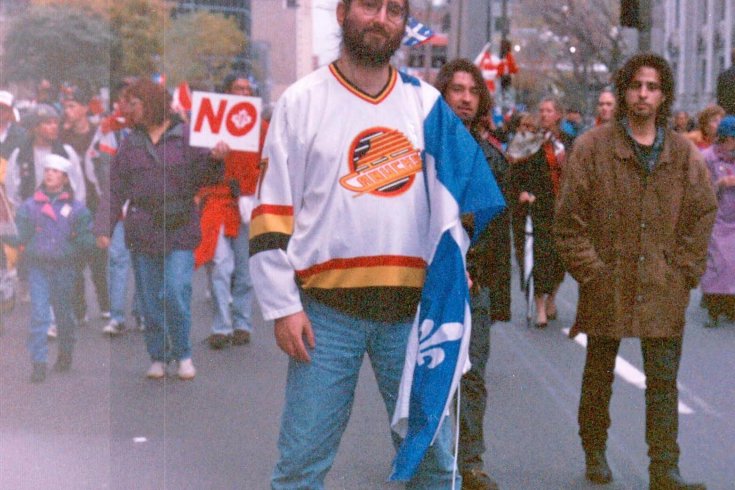

I felt queasy about the idea of carrying a flag—being that blatantly patriotic seemed un-Canadian to me. In order to show where I was from I’d decided to wear my Vancouver Canucks jersey. McLellan thought this was a great idea. “Most Quebecker won’t recognize a BC flag—but they all know the Canucks.”

The woman in front of us was a bilingual Franco-Ontarian woman in her thirties who lives in Vancouver. She and her husband had been discussing what a lovely idea the rally was, but how they couldn’t really afford to attend it—when Bloc Québécois leader Lucien Bouchard came on TV and snidely dismissed the people coming out for the rally as the citizens of “English Canada.” A moment later they had agreed that when they were ninety, she could look back to say she’d done her best to help her country, and $200 wouldn’t seem like all that much money.

And what’s your story, she asked me? Since I’ve identified everybody else by age and relationship to Quebec: I’m thirty-three and unilingual, although I’ve got basic comprehension of French. I’ve been to Quebec four times in my life including this one—all of which add up to a grand total of twelve days in la belle province—and as corny as it may be to admit it, I like the idea of being part of a country that can stay together and thrive despite, or perhaps because of, the linguistic and cultural differences that Bouchard and Parizeau say demand the creation of a separate nation.

Until less than forty-eight hours before hopping that flight my participation in the referendum was going to consist of watching the news reports, crossing my fingers, and making the occasional rude comment about Bouchard. Then I got a call from my friend Donna Wong-Juliani, who was born in Montreal and speaks fluent French, telling me about the rally and the reduced fares. Five minutes later I was asking my wife if she’d mind me disappearing to Montreal. By 12:15 p.m. I had a seat on one of the last available flights out. Like most of the people I spoke to I had a million good reasons not to fly to Montreal that day, but I suspected that all of them would have sounded pretty hollow the following Tuesday morning if Quebec voted “oui” and I hadn’t gone.

At one point I asked a flight attendant how many people on the plane to Toronto she thought were heading to Montreal. She estimated about half of the 170 passengers were off to the rally. And this was a business express flight to Toronto—not one of the special unity charters. She also told me that another passenger had asked her to make an announcement to find out if there was a rally organizer on board, but there were none. No one I met had talked to anyone other than perhaps their significant other before deciding to do this bit to help save the country.

My impromptu interviews were cut short by the in-flight movie, Crimson Tide, which felt somewhat appropriate—two men yelling at each other at high volume, both convinced they’re right, the other is wrong, and that the fate of the world hangs in the balance.

When the plane landed the attendant did make one special announcement, which was greeted with cheers and applause. “For those of you off to Montreal for the rally, good luck.”

Waiting in the departure lounge in Toronto, the mood was almost festive.

Rob Haggarty, a high school teacher from Bonneville, Alberta had a Canadian flag laid out on the ground in front of him. People were gathering around to sign it. Haggarty said he’d asked students at his school to autograph it, then he took it to the local junior high school, and then to the elementary school—he got the signatures of just about every kid in Bonneville, and “just about everybody” on his flight out from Alberta.

Chris Wooten, who was sitting across from the impromptu flag-signing ceremony, commented, “It reminds me of going to anti-war rallies in the ’60s.”

When I told people I was going on the save-the-country express, I expected to be teased about it. After all, it’s pretty hokey to fly almost 4,000 kilometres just to wave a flag and sing the national anthem. Instead, I had people thank me and tell me they wished they were going. My dad the Reform Party supporter asked me to “hug a Quebecker” for him.

That seemed to be about the response everyone got from their friends. On the connector flight from Toronto to Montreal, the woman beside me, Torri Enderton, told me one of her coworkers at the BC Court of Appeal stuffed a $10 bill in her hand when he heard she was going. “For a couple of drinks,” he said. Enderton said she and a friend had started a petition to show their support for Quebeckers when they got to work that morning. By the time they left at 2 p.m. to catch their flight they’d collected seven full pages of names. The two of them had bought small BC and Canada flags at Eaton’s. When they got to Montreal they planned to find Quebec flags to complete their set. Enderton had never been to the province before, but this was something she had to do. Why? “If every one of us convinces one person . . .” she said. She didn’t finish the sentence, but she didn’t have to.

When the flight landed in what I realized could soon be a foreign country, a French-Canadian attendant announced, “I would like to extend a special welcome to all of you who are coming to Montreal with a cause that’s very dear to their heart.” Although the message didn’t indicate which side he was on—everybody applauded and cheered.

At the luggage carousel I spotted Much Music VJ Terry David Mulligan. The moment he told me he was covering the event for Much I realized this was Canada’s Woodstock. I half expected that when I got to the rally the organizers would broadcast warnings that “There is some bad maple syrup out there.” And, like Woodstock, I suspect that a few years from now half a million people would remember being crowded into Place du Canada at noon on October 27, 1995.

On the airport bus to downtown Montreal, I ran into my first and only “ugly Canadian” of the trip—a fifty-something businesswoman from Victoria who stepped on the bus and loudly proclaimed: “Are you guys happy to see all of us? You better be.” She then began bleating about the economic impact of separation to anyone unable to get out of her way.

The other passengers on the bus included two black-clad, beret-wearing teens from Winnipeg who had never been to Quebec. They had come “because we had to.” They didn’t know where they were going to sleep that night but they didn’t care, all that mattered to them was that they’d made it.

The next day—rally day—my friend Donna and I decided to head out early “to beat the crowds.” After she’d bought herself a Canucks jersey at Le Baie we walked down St. Catherine looking at all the people with flags in their hands, maple leafs painted on their faces, and hope in their hearts.

When we arrived at 10:30 a.m. the streets were already packed. Donna spotted some perplexed-looking RCMP officers moving in a set of metal railings to keep the crowd from getting too close to the speaker’s platform. She and I attached ourselves to one of the railings and held onto it as the police moved it. When it was finally in place, we found ourselves about two metres away from the corner of the platform.

How good was our view? When the speakers mounted the platform an hour later, the person directly in front of us, on the other side of the railing, was Ontario Premier Mike Harris. Harris was wearing a new baseball cap—at least I hope it was new because he hadn’t removed the price tag.

At eleven o’clock, a speaker announced that someone had found a bag belonging to Margaret something and the crowd began chanting “Margaret, Margaret . . .” At 11:05, I heard the first of numerous spontaneous and buoyant renditions of “O Canada,” each of which was endowed with the same depth of feeling rarely heard in this country outside of a Remembrance Day march, a military funeral, or the original Canada Cup series when we took on the Russians.

At about 11:15, a tiny old woman started forcing her way through to the front of the crowd using her elbows with the practiced skill of a professional hockey goon. At about 11:20, she attached herself to my arm to keep from falling over, then held on tightly for most of the next two hours. She told me she was from Richelieu, a half-hour outside of Montreal. I think she said she’d taken the bus, but between the crowd noise, the French pop music blaring from the loudspeakers, and her thick accent, I’m not prepared to guarantee any of these facts. She also tugged on my arm occasionally to point out local celebrities, like Jean Charest’s kids and a popular Montreal MP.

As my new buddy was catching me up on the local colour, a man on the other side of the railing started tossing flags to the crowd—real, full-sized flags. The next thing I knew I had a Quebec flag in my hands. I wasn’t sure what to do with it, so I slung it over my shoulder and suddenly there I was, wearing a Vancouver jersey with a fleur-de-lis cape. My transformation to Captain Canuck was completed when Donna stuck a paper Canadian flag in my ponytail holder and then the old woman handed me a small Quebec flag to put in my hair to complete the set.

Under normal circumstance I would have felt ridiculous—but there was nothing about this event even remotely related to normal. I was surrounded by people of all ages who had drawn maple leafs and fleurs-de-lis on their faces, plastered their skin with “non” stickers, and dressed themselves in various combinations of Canadian flags. Meanwhile, the biggest flag I had ever seen was moving through the rally like a living creature. In this crowd I was inconspicuous.

When Jean Charest began to speak the old woman began tugging frantically on my arm again. I turned from watching to find her pushing my other arm toward a man in a snazzy dark business suit. I smiled and said “I’m from Vancouver,” and just as I finished I realized I was shaking hands with Frank McKenna.

“I’m out from New Brunswick,” he said. “Glad to have you here.”

Next the old woman tugged me again so I’d lean down. She beamed at me and shouted, “You came all the way from Vancouver. Now you will be on TV with the prime minister of New Brunswick.”

I was told later that the TV newscasts focused on the speeches—but the speeches were almost irrelevant.

As powerful as Jean Chrétien or Jean Charest’s words may have been, they weren’t as poignant as the man holding the municipal flag of the city of Yellowknife, the woman with the cardboard sign that read “Edmonton, Alberta loves Quebec” or all the people from across the country who, like myself, had never waved a flag in their lives and were now proudly holding a fleur-de-lis and a maple leaf to show our support for a united Canada.

No one was there to hear the speeches—the only statement that really mattered was we had come from all over Canada. The biggest cheer came when a speaker announced that the crowd was estimated at 150,000. I suspect that if the politicians hadn’t interrupted, the spontaneous renditions of “O Canada” punctuated by chants of “Ca-na-da!” would have lasted all afternoon.

I could try and be cynical and witty or at least hip and ironic about my feelings as I looked out at the mass of people, but if I did I’d pretty much deserve to burn in hell. Bouchard was right, it was a love-in, but we didn’t just come out for the people of Quebec. We were there for ourselves too because, for one brief moment, it felt like we might be able to make a difference.

As the crowd was dispersing the old woman tugged one last time and pushed a slip of paper into my hand. It had her address on it. She thanked me for coming and told me to write her and tell her what I thought. Then she grasped my hand and we hugged each other.

After she left, Donna and I walked away in our Canucks jerseys—or at least tried to walk away. We were stopped every few moments by someone asking if we were really from Vancouver. Then, after a moment where they appeared to get lumps in their throats, they’d thank us for making the effort to help, and we’d wish them well on Monday. “You came from Vancouver, thank you so much,” they’d say—some with English accents, some with French.

Sitting in Schwartz’s Deli after the rally, sampling their legendary Jewish junk food, we heard a man at the next table asking another man if he was really from Vancouver and if he’d really come all this way to help. He was and he had. I asked him if it had been worth it and he smiled and said that he loved Canada, he loved Quebec, and that this was just something he had to do.

On the flight home the attendant told me that even though she wasn’t able to attend the rally, being able to talk to so many people about the event feel a part of it. Then she said she felt better knowing that whatever happens on Monday night, at least we tried. Yeah, we did.

Just before sitting down to write this I unfolded the slip of paper I’d been handed by the old woman at the rally—her name is Marie-Josephte Champagne. Well, Marie-Josephte Champagne, this is what I thought. Whatever happens now, we tried—and none of us who were there will ever forget it. I hope that whatever happens next, Quebec doesn’t either.

A version of this article was originally published in the Vancouver Courier.