It is a sunny July morning in a Kitchener-Waterloo courtroom, a bright space reminiscent of a non-denominational church. I am the only spectator, sitting at the edge of the front-row pew. A door opens, and two armed guards escort in a young woman, her small hands tightly bound and crossed at the wrist by plastic cuffs that pinch her skin. Her legs are shackled, so her gait is odd, slow. When she arrives at the prisoner’s box, her chains are padlocked to the floor. The guards position themselves tight to either side of the box.

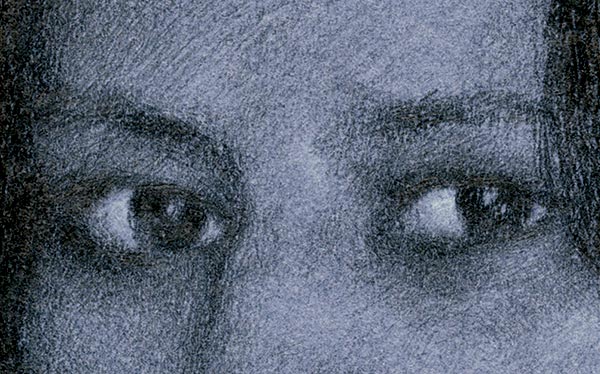

The woman is dressed in white A-line pants and a long-sleeved white blouse over what appears to be an orange tank top. She looks like a young nurse. The room is cold; she fidgets, rubs her wrists, takes in her surroundings, glances briefly at me. We’ve spoken but never met. She is slim, fine boned, and taller than I had imagined, with a straight back and a heart-shaped, solemn face and bright brown eyes. She is very beautiful.

Her name is Renée Acoby, and she is considered by the Correctional Service of Canada (csc) to be one of the country’s most violent women. She rarely goes anywhere without her legs shackled, her hands cuffed, and between two and five armed guards beside her. She is in this sunny courtroom because the attorney general of Ontario has agreed to an application to have her classified as a dangerous offender, following a series of hostage takings at several different jails, particularly a 2005 incident at the nearby Grand Valley Institution for Women.

Born in 1979 in Manitoba, Acoby went to prison in 2000 on charges including trafficking in a scheduled substance and assault with a weapon. Her sentence was three and a half years. Since then, she has accumulated an additional eighteen years of time for offences committed within the corrections system, putting her in the tenth year of a twenty-one-and-a-half-year sentence. She has never been paroled, nor even applied for parole. The only time she leaves the segregation unit of one of the numerous Canadian prisons in which she has been incarcerated is for court appearances like this one.

On the phone with me, Acoby has revealed a mercurial disposition and a sweet, light voice and laugh. She has another voice, too, which I’ve never heard. I’ve heard her speak in desperation but not in anger. She admits to a volatile temper, though, and says she is “pigheaded.” She has spoken to me of having been “blinded by rage” in the past.

The judge takes note of her obvious discomfort and indignation in the prisoner’s box, and remarks that she need not be handcuffed. The prosecutor and the police officers hastily intervene. She could grab a weapon; she could grab a pen and turn that into a weapon. “She has a history of using improvised weapons,” one of them says. The judge orders that ordinary handcuffs be brought in instead. Eventually, they are.

Only two women have ever been labelled dangerous offenders in Canada. The first, Marlene Moore, committed suicide in the Prison for Women in Kingston in 1988. The second, Lisa Neve, had her sentence overturned in 1999. For Acoby, classification as a dangerous offender would mean an “indeterminate” sentence, and life on parole were she ever released. The fundamental questions being asked in her hearing are deceptively simple: Is this inmate likely to reoffend? And if released, could she control her violent tendencies?

These are difficult questions, in part because most of Acoby’s criminal history has unfolded deep within the country’s corrections system. She has lived almost entirely in solitary confinement for nearly six years, spending twenty-three hours each day alone in her cell. In 2004, she became one of the first to be placed on csc’s Management Protocol, a special category of punishment designed for women prisoners who have been involved in a major incident causing serious harm or threat while in the system. This anodyne-sounding regime consists broadly of a three-step program of segregation, partial reintegration, and, finally, transition to a regular maximum-security cell for at least three months. Offenders must earn their way from phases one through three and then off the Protocol, largely by avoiding aggressive behaviour. Most fail to do so—too many snakes, not enough ladders.

As of fall 2009, Acoby was one of four women covered by the Management Protocol. All are aboriginal, from among the almost one-third of women in federal penitentiaries who are of aboriginal descent. Seven women have been on the Protocol since it was created—one was taken off it last fall, perhaps not coincidentally after threatening a Charter challenge.

In his 2008–09 annual report, federal corrections investigator Howard Sapers wrote of the Protocol, “I have very serious concerns about the impact of this form of harsh and punitive confinement on the mental health and emotional well-being of these women. They need intervention and treatment, not deprivation. I think most Canadians would agree that in the 21st century there must be safer and more humane ways for our correctional system to assist a handful of high-needs women offenders.”

But the debate over the Management Protocol comes at a time when Canada’s attitude toward crime and punishment is hardening, with the federal government engineering a hastily designed retrofit of our justice and penal legislation that will affect everything from sentencing to parole to segregation to judicial discretion. A Roadmap to Strengthening Public Safety, the Conservatives’ bible for their populist “transformation” of csc, is described by academics Michael Jackson and Graham Stewart in their critique A Flawed Compass as “deeply regressive,” based on a vision that will have a “great detrimental impact on the protection of human rights and effective corrections.”

Indeed, the Roadmap never once mentions the human rights of prisoners, and deals only perfunctorily with the issue of segregation, or solitary confinement (a major component of the Management Protocol), which Michael Jackson calls “the litmus test of legitimacy for csc, because it is the hardest thing to get right.” This superficiality is especially troubling because, in the fall of 2007, while the Roadmap was being finalized, nineteen-year-old inmate Ashley Smith committed suicide in a segregation cell at Grand Valley Institution, witnessed by several corrections staff. Kim Pate, executive director of the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies (caefs) says, “The level of confinement in isolation is so dehumanizing it is a violation of the Charter, security of the person, and international human rights standards.”

Concerns about the human rights of Canada’s women prisoners in turn raise an important practical question: is it possible that the policies and practices of federal institutions for women might actually be helping to create the criminality they’re designed to prevent? In other words, has the system helped to create Renée Acoby?

What I have seen of Acoby’s accumulated criminal record follows a narrow, unwavering narrative line: difficult childhood, delinquency, incarceration, violence, recalcitrance, escalating punishments, a determination of incorrigibility, and finally, in the courtroom in Kitchener-Waterloo, the potential for the worst possible sentence. In the court transcripts that I have had access to—which in turn allude to social welfare reports, psychiatric evaluations, and csc files that I have not—it also seems to be a story larded with racist bias and incendiary psychiatric speculations.

A more humane version of Acoby’s story might begin with a bright, fierce child caught in the fan of adult actions and passions. It would allude to timeless, tragic motifs: a father who murders a mother, a grandfather who kills himself after the brutal murder of his daughter. An aunt who betrays the child unwittingly, with terrible consequences, but who is still loved. The child who lost her mother in turn becoming a mother who loses her child.

Acoby was six months old when her father murdered her mother. She and her siblings were brought up by a loving grandmother who struggled with diabetes, addiction, and heart problems. It was only when Acoby was nine that she learned, in the chance overhearing of a conversation, that her grandmother was not her mother. “So everyone has lied to you,” she told me one evening on the phone. “Your picture of your family falls apart.” Forgiveness came slowly, much later.

According to the official record, from the age of twelve Acoby was angry, defiant, and in serious trouble. She spent several periods in secure custody for such offences as theft under $1,000, theft under $5,000, setting off false fire alarms, public mischief, assault, dangerous operation of a motor vehicle. Four days after her twenty-first birthday, in 2000, she was sentenced to three and a half years and sent to the Saskatchewan Penitentiary. She was pregnant at the time.

Approximately two months into her term, Acoby participated in a hostage taking, a strategy some women inmates use, often collectively, to make a point about prison conditions. The official record refers to the possibility that the incident was staged, but its aims were real enough. According to the prosecution’s statement, the women “demanded to see a mental health nurse; they wanted coffee and water; they wanted feminine supplies, sanitary napkins, that sort of thing.” Acoby’s role in the hostage taking is unclear from transcripts: in what became a pattern, she chose not to defend herself against the charges. “I’m taking responsibility for my actions,” she said. “I just want to plead guilty… I’d like to get sentenced today.” The plea added three years to her sentence.

That fall, Acoby gave birth to a daughter. csc changed her security designation from maximum to medium, allowing her to go to the Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge for aboriginal inmates in Saskatchewan, where her baby could be with her at all times. She was even permitted to make one escorted journey away from the prison with the infant, to visit family. Parole began to seem like a possibility.

But when the baby was eleven months old, Acoby, then twenty-two, did drugs with other prisoners—a temptation she had previously resisted, despite ready access. Prison staff removed the baby that night, then sent her to a relative in another province the next day. Acoby (who was still breast-feeding) was permitted to see her daughter briefly that morning, a moment she wrote about a few years later: “I spent those five minutes memorizing every detail of her beautiful little face, holding her and telling her how much I loved her. It was the hardest thing I had to do in my life—to turn my baby over to the care of someone else. I spent hours crying and praying for [her] health and happiness, and I hoped that one day I would have her back with me.”

Almost immediately after she lost her child, she attempted to escape, taking a correctional officer hostage. Again, she refused legal aid and pleaded guilty. During sentencing, she had this exchange with the judge:

“Because they took her away from me, that’s why I did it.”

“Well, now she will probably be taken away from you permanently.”

“I know, and that’s probably the worst kind of sentence… So what you give me is not going to make a difference.”

Her sentence was extended to ten and a half years. She would not see her daughter again for seven.

In several prisons over the next three years, she committed still more offences: uttering threats, forcible confinement, assault causing bodily harm. Her sentence went from ten and a half, to fifteen and a half, to eighteen years. As one judge noted in sentencing her, “You’ve heard the expression ‘life on the installment plan.’ I think I’m seeing it here.”

Acoby was put on the Management Protocol in July 2004, after two assaults on fellow prisoners. Over the next six months, she worked her way into the third phase of the regime, which meant she was no longer in segregation and was sometimes allowed to go unshackled within the maximum-security unit. According to Acoby, she was scheduled to get off the Protocol in January 2005, but the deadline was altered (several times, she says), and her fury at what she saw as a betrayal of trust ignited the hostage taking at Grand Valley.

According to court documents, on August 22, 2005, Acoby and another inmate captured two staff members and tied them to chairs with electrical cord and bandages, then put belts around each of their necks and gauze over their eyes. The inmates force-fed medications to the hostages and threatened to cut their throats and gouge out their eyes. Acoby brandished a shank made from a toothbrush and a sewing machine bobbin. She burned the arm of one of the hostages with a cigarette, then poured water down the woman’s arm to ease the pain.

After the incident, she told one of the hostages that it had not been “personal”—that their anger was directed at the institution. The other inmate was sentenced to three and a half years; Acoby pleaded guilty and now faces the dangerous offender application. Since 2005, she has committed one additional hostage taking and a few minor offences, all of which have been introduced into the dangerous offender process (which will resume in September 2010).

Acoby’s record of offences in prison is striking in that it is almost entirely about perceived injustices to her or to other inmates. “As far as I’m aware,” Pate says carefully, “every incident in which Renée was involved was preceded by her using every other mechanism available: complaint, grievance, appealing to the warden and to anyone else in authority. Every single incident was preceded by her trying to use all the legitimate mechanisms first.”

Pate believes Acoby is motivated in part by a “righteous rage” born of the banishment of her child. Since their separation, she has only seen her daughter—who does not know that Acoby is her mother—once, a visit during which she was shackled and handcuffed. “Many women in prison, when they have that kind of devastation, will implode, start self-injuring, get depressed,” says Pate. “Some have suicided. But Renée is a survivor. She learned from a very early age that you have to fight back and never show your weakness. So instead of weeping or being depressed and asking for meds and slashing and trying to kill herself and every other woman, she acts.”

In my experience, Acoby is well spoken, intelligent, and articulate. She reads voraciously, writes well, and takes correspondence college courses that, according to her lawyer, she typically all but aces. She has a sophisticated understanding of prison policy, commissioners’ directives, and research papers. And she knows the Management Protocol practically by heart. In 2008, she wrote in a notebook, “One need only look at the durations the women have spent on the Management Protocol to deduce it is not a successful OR humane model of confinement. I find it reprehensible that [those] who designed the Management Protocol with the ‘special needs of women offenders taken into consideration’ cannot even meet with us. Perhaps they don’t want to confront the ghosts of women their brilliant Protocol has reduced the women to.”

The systematic incarceration of Canadian women dates back to the 1830s. For decades, female prisoners were housed in sections of penitentiaries for men, where they were placed in separate wings and made to work in the kitchens and laundries, subject to the same discriminations they experienced in Canadian society. By the 1920s, reformers were arguing that women should be housed apart from male inmates and guards, ultimately leading to the creation of the Prison for Women (p4w) in Kingston. The new institution opened in 1934, and started coming in for criticism not long after.

Between 1938 and 1990, p4w was condemned in no fewer than fifteen different reports. Famously described in 1977 as “unfit for bears, much less women,” the prison was, in Madam Justice Louise Arbour’s words, an “old-fashioned, dysfunctional labyrinth of claustrophobic and inadequate spaces.” Programming was poor, inmates were far removed from their families, and the morale of inmates and staff was abysmal. Lockdowns were common, and suicide and self-mutilation occurred with worrying frequency; between 1988 and 1991, six inmates committed suicide there.

In 1989, the commissioner of csc set up a task force to examine the treatment of female offenders and review the future of the prison. The task force consisted of corrections officials and civil servants, as well as such non-governmental representatives as caefs (which co-chaired) and the Native Women’s Association of Canada. The debates that arose from this unusual and idealistic bipartisan arrangement resulted in some significant silences in the task force’s final report, Creating Choices, notably with respect to high needs/high risk offenders. The task force was unanimous, however, in recommending that p4w be closed and replaced with regional prisons featuring cottage-style housing—an approach partly designed to ensure that inmates could be housed in facilities near their own families and communities.

Four years after the release of Creating Choices, on April 22, 1994, with work under way on the new facilities, a violent clash between p4w inmates and staff resulted in an extraordinary intervention by an all-male emergency response team. The men pulled prisoners from their cells, conducted strip searches, and left the women in body belts and leg irons, naked save for paper gowns, on the floor for several hours. In 1995, a videotape of the confrontation surfaced after being suppressed by the csc, prompting Solicitor General Herb Gray to order a Commission of Inquiry into the incident. He appointed Arbour to lead it.

Arbour’s 1996 report catalogued the “ongoing infringement of prisoners’ legal rights at the Prison for Women over many months” and probed the “cruel, inhumane and degrading” treatment of inmates. It also denounced csc’s decision to enforce a “seriously harmful” eight- to nine-month segregation period at p4w after the clash. “If prolonged segregation in these deplorable conditions is so common throughout the Corrections Service that it failed to attract anyone’s attention,” she wrote, “then I would think that the Service is delinquent in the way that it discharges its legal mandate.” Her overarching conclusions were unequivocal: “The absence of the Rule of Law is most noticeable at the management level… there is nothing to suggest that the Service is either willing or able to reform without judicial guidance and control.”

Between 1995 and 2000, when p4w finally closed, federally sentenced women were gradually transferred to other institutions, including five new ones: the Edmonton Institution for Women; the Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge, in Maple Creek, Saskatchewan; Grand Valley Institution for Women, in Kitchener; the Nova Institution for Women, in Truro, Nova Scotia; and the Joliette Institution, in Quebec. (In 2004, a sixth, the Fraser Valley Institution, opened in Abbotsford, BC.) However, with new prisons came new problems, especially when it came to the most difficult-to-manage inmates.

University of Alberta professor Stephanie Hayman, who published a book in 2006 on the implementation of the ideals and objectives of Creating Choices, found that the entrenched bureaucracy and practices of the prison system had triumphed over the good intentions of reformers. Those “good intentions” reflected a bias toward the notion that women who have committed crimes are themselves victims. Because of philosophical differences within the task force, Creating Choices had neglected the possibility that some women offenders might require “enhanced” security. As Hayman noted, “In refusing to deal fully with the difficult-to-manage women, and in being reluctant to accept that women’s violence was not always linked to their victimization, the task force presented csc with the opportunity to define the problem and to decide upon the solution.”

csc’s first major initiative was to considerably expand the new prisons’ external security and segregation capacities. In 1999, it introduced the “Intensive Intervention Strategy,” which provided for perimeter fencing and new secure units—largely maximum-security and segregation cells—under the assumption that 10 percent of federally sentenced women would require extra supervision. By 2005, the number of beds in mental health or secure units had reached almost 25 percent.

In 2004, csc introduced a new element of the Intensive Intervention Strategy: the Management Protocol. The Protocol’s primary aims, as csc defines them today, are to “ensure safety of staff, other inmates and the public, as well as the opportunity for the inmate to regain her credibility and slowly reintegrate back into the regular maximum security population.” Methods include stabilizing a routine, establishing intervention methods, maintaining staff-inmate interaction, and providing for psychological assessments and interventions, spiritual activities, and leisure. csc estimates that an inmate will likely need at least six months to complete all three steps.

But hardly anyone ever gets off the Protocol, perhaps because of this rule: “There will be a zero tolerance for any aggressive behaviour (physical or emotional).” According to Howard Sapers, the federal corrections investigator, there is an arbitrary, defeatist element to the regime: “The standards of behaviour offenders must meet to be moved down the sliding scales of the Protocol are almost always security focused, and extremely difficult to assess or meet. There are few to no correctional programs or leisure activities available to women on the Protocol.”

Pate cites restrictions on things that by law should be allowed, for example “writing instruments and paper, which prevents women from using legal processes like grievances to challenge lack of compliance with law.” She says that csc also sometimes interferes with family visits, even though, she asserts, “Corrections’ own research indicates that the single most important indicator of someone’s success after prison is the extent of their interaction with family.”

Some aspects of the daily reality of the Protocol seem absurd, picayune. According to Acoby, she has in the past had to earn her way to more than ten squares of toilet paper, and has been required to clean her cell with a face cloth and hand soap until she earned the privilege of a mop, a broom, and real cleaning fluids. For several months at a time, she says, meals were brought to her cell in paper cones, “like Dixie cups.” She has been prohibited from brushing her teeth more than once a day. And she has been told that she must not use profane language for thirty days. (Her response was to swear a blue streak for several days, until the condition was withdrawn.) As one corrections official said to Pate, “This would be a Monty Python skit if it weren’t real life.”

But the most troubling element of the Protocol, and its centrepiece, is solitary confinement: twenty-three hours a day in the first phase. Michael Jackson, a law professor at the University of British Columbia, calls solitary “the most individually destructive, psychologically crippling, and socially alienating experience that could conceivably exist within the borders of the country.” Arbour’s 1996 report cited evidence that the effects of solitary may form a clinically distinguishable syndrome, leading to “perceptual distortions such as hallucinations, affective disturbances such as massive anxiety, difficulties thinking, disturbances in thought content, problems with impulse control and rapid subsidence of symptoms on termination of isolation.” Such findings, she wrote, “support the conclusion that prolonged segregation is a devastating experience, particularly when its duration is unknown at the outset and when the inmate feels that she has little control over it.”

“People cannot tolerate a situation in which there seems to be no escape,” says Jackson. “If Acoby feels there is no escape and, knowing her own limitations, fears she cannot put together a month or two of good behaviour without some infraction that sends her back to the previous phase, then she is in a situation where there is inescapable pain and inescapable punishment. It is the ultimate horror, and it leads to this cycle of violence.”

Twice during 2006 and 2007, Renée Acoby was incarcerated on a segregation unit at Nova Institution in Truro alongside a young woman named Ashley Smith. Smith first entered the criminal justice system at the age of fourteen. Between 2003 and 2006, a period she spent mostly in segregation, she was the subject of upwards of 800 incident reports and 500 institutional charges, and was cited for at least 168 self-harm incidents. At eighteen, she entered the federal system, and in less than a year was transferred seventeen times between numerous correctional institutions and treatment facilities, in segregation the entire time. I’ve seen two videos of Smith; she clearly had an enormously engaging personality, and also clearly suffered from profound mental afflictions. (Acoby describes Smith with affection, as “one of those kids you want to hug and scold at the same time.”)

In August 2007, the two were in cells next to each other at Nova. The segregation unit consists of cells with reinforced doors featuring a food hatch. Inmates cannot see one another; they communicate by yelling. Smith was a high-needs/high-risk inmate, who shouted out incessantly and frequently threatened to strangle herself. According to evidence presented at Acoby’s dangerous offender hearing, Smith was pepper sprayed numerous times. She was prohibited from having anything whatsoever in her cell, including writing materials, and was denied sanitary supplies, even underwear, when she was menstruating.

Because Smith was not given pen or paper, Acoby wrote out several grievances on her behalf, which were dismissed by csc because they weren’t written by Smith herself. Then, onthe hot and airless evening of August 17, Acoby took a guard hostage for more than two hours, demanding that she be transferred to another institution. Videotape of the event was shown at the dangerous offender hearing. It shows Acoby wielding a sharp object, then tying the victim’s ankles with her shoelaces and resting her on the floor. Acoby was occasionally agitated, yelling about being taken seriously. She wanted outside negotiators and asked that Kim Pate be called.

Although the standoff was obviously traumatic for all involved, it was also a curiously static incident during which, according to the hostage, Acoby tried not to hurt her. Twice, a bottle of pop was passed through to Acoby; each time, she offered it first to her victim.

Abruptly, while management was still considering Acoby’s request for transfer, she released the hostage unharmed. Both she and Smith were transferred out of Nova within days—Acoby to Edmonton and Smith to Grand Valley. At Grand Valley, Smith was placed on suicide watch, with a guard monitoring her from outside her door. According to Sapers’ report, A Preventable Death, she had “no clothing other than a smock, no shoes, no mattress, and no blanket. During the last weeks of her life she often slept on the floor of her segregation cell, from which the tiles had been removed.”

On October 19, 2007, Smith died. Three front line corrections officers and one manager were charged with criminal negligence in her death, but fourteen months later, after ten days of pretrial hearings, the charges were dropped suddenly because medical experts concluded that the guards could not have reached her in time to prevent her death. During the proceedings, prosecutors showed a videotape of her last moments, filmed by one of the corrections officers, who stood outside her cell, unable to open the door without radioing a request to a manager sitting in front of a computer on the other side of several closed doors.

In the corner of the cell farthest from the door, Smith is wedged between a bare bed frame and the concrete wall. She is face down, on her knees, wearing nothing but a short, colourless “suicide gown” that theoretically cannot be torn to make ligatures. When she twists her head, her right cheek is revealed, and it is undeniably purple. The only sound from inside the cell is a ragged gasping of breath. Long intake. Silence. Long intake. Silence. Silence. Intake. Silence. The only sound from outside the cell is an occasional comment or aside from a guard. During an interminable twelve minutes, the guards watch, entering briefly once, possibly to remove a ligature, and again just after seven in the morning, when three or four guards enter the cell and a commotion erupts: “How do we know if she isn’t breathing? ” “Does anyone have a cpr mask? ” Someone screams in the cell next door. A guard yells, “Shut up!” Smith is pulled out from beside the bed. She is dead.

In June 2008, Sapers reported “a litany of serious failures leading up to the tragic and, I believe, preventable death of Ms. Smith.” He cited a fatal congruence of individual and system failures: inadequate attention paid to mental health issues and grievances, and the unconscionable use of prolonged segregation. He noted that an independent psychologist “interpreted Ms. Smith’s self-injurious behaviour in part as a means of drawing staff into her cell in order to alleviate the boredom, loneliness and desperation she had been experiencing as a result of her prolonged isolation. This behaviour was Ms. Smith’s way of adapting to the extremely difficult and increasingly desperate reality of her life in segregation.”

According to Michael Jackson, Smith and Acoby were both likely scarred by the horror of isolation. “Smith took her own life; Acoby acted out against the staff,” he says. “They were both trying to demonstrate that they needed help, [in a position] where you believe no one cares about you.”

The Management Protocol is a “purgatory of segregation,” says Jackson, “because there is no escape route from the rigours of the regime. Someone like Acoby has huge issues of anger and hostility to authority. But the measure of her progress is that she has to control her anger and demonstrate respect for authority. Because her skepticism of authority is so deeply embedded, no matter how she tries, the gates [to getting off the Protocol] are closed.”

Pate, who has known Acoby for ten years, says, “I don’t support it all—her staging a hostage taking or taking someone hostage, she’s done both. But I think they were desperate measures, where she felt it was the only way to get attention to the issues she’d already tried to address. It doesn’t justify her actions. But at one point they were saying, she’s unpredictable, she’ll turn on you, and that’s not true.”

“What she needs is people in whom she can trust,” says Jackson, “people who will not judge and condemn her for everything she does. Other prison systems have found ways of dealing with similarly higher-risk offenders without locking them up like Hannibal Lecter.”

Although the Canadian system has unquestionably improved since the closure of p4w, and Pate and others have encountered many sympathetic officials and front line workers over the years, observers such as Howard Sapers believe a new approach for high-risk/high-needs women offenders is urgently required. In his 2008–09 annual report, he was unequivocal: “The Management Protocol for women offenders should be immediately rescinded pending further review by an external expert in women’s corrections.” In its formal response to the report, csc stated that it is “currently reviewing its strategy for managing higher risk women with a view to moving away from the Management Protocol.”

As for what that should mean in practice, Sapers, caefs, and others have consistently reiterated Arbour’s 1996 recommendations for an external judicial process to oversee the use of segregation. They have also sought to genuinely empower the prison system’s Deputy Commissioner for Women, a position created after the Arbour report. Such recommendations have in the past been repeatedly denied; none is likely to be implemented in the government’s current transformation of csc.

The extent to which Canada’s penal system has helped create Renée Acoby is difficult to measure in part because speaking with her is not encouraged. I managed to talk with her on the phone in the fall of 2008, and asked her if she would be the focus of this story. She courageously agreed, saying she would “gladly do it, not for me but for other women.” I then submitted a written request for an interview to the warden of the Edmonton Institution. Although csc is in principle dedicated to openness, including freedom of expression, association, and the press, it maintains complete discretion over interactions between inmates and journalists, and it chose to deny my request. After both Acoby and I followed up, we were given several reasons: because of security and operational concerns, because it might place Acoby’s victims at risk, and because she herself had not submitted a request (though she says she did). Twice, I was granted permission by staff at the Edmonton Institution for telephone contact with her, but that permission was abruptly withdrawn without explanation.

After Acoby was temporarily moved to another institution, we managed to speak a few times, sporadically. When she called, she was sometimes preoccupied with recent events, such as the day when “the bad apples” were in charge and she wasn’t permitted to send birthday greetings to her daughter. Or the several days when she’d covered her cell window and refused to emerge. Or the day she ripped up some of her clothing because she was sick of wearing the same thing (she was allowed to shower only once a week, and hadn’t been out in the fresh air for months). Another day, she’d lost her temper and was facing charges for uttering threats.

Acoby admitted to feeling badly about “being a jerk” with some of the front line workers, but insisted on pushing for access to course books, for example. “I need my brain to stay busy, otherwise I have too much time to brood about stuff,” she said. She seemed conscious of the need to control her anger, and longed to get her security lowered so she could connect with her daughter. But until then, she said, “I can’t disrupt her life.”

She was clearly hungry for contact, for conversation. She described to me, with pride, a one-month stint in 2006 in the maximum security unit of a provincial facility near Sarnia. “The officers there aren’t afraid of me. When I arrived, a white-shirt said to me, ‘We know all about you, but I just want to ask you one thing. If we unlock you with the other girls, are you going to give us problems? I said, ‘Absolutely not.’ And they unlocked me for the whole time I was there.”

During a lull in the proceedings at the dangerous offender hearing in Kitchener-Waterloo, I asked one of Acoby’s guards if I might speak with her. Unexpectedly, the senior police officer said he didn’t see why not, so I went over and introduced myself. We had spoken perhaps four times by that point.

“Hello, Renée,” I said. “I’m Marian.”

She smiled, and her face lit up. We talked for ten minutes: About her daughter, who has become more real to her now that the girl is older, and because she gives her mother a reason for behaving well. About her concerns regarding her family being hurt by news coverage of the proceedings (“They are doing well; they have jobs and lives,” she said). About books, since I had sent her a collection of short stories by Joseph Boyden. I mentioned that I was thinking of going out west, where she grew up, and she said she hoped I might meet her sister.

When the judge returned, we stood, and I said, “It was nice to meet you.”

“Thanks a lot for coming,” she replied.

Acoby’s 2008 notebook entry about women being turned into ghosts by the Management Protocol stays with me. I do not know the names of the other women in the system; regrettably, the only way their identities could surface would likely be in a courtroom. They are effectively silenced.

A few weeks later, I did go west, to Manitoba. Though I wasn’t able to connect with Acoby’s sister, I met a cousin of her mother’s and spent an hour with one of her uncles, a soft-spoken, thoughtful man with sad, dark eyes. He showed me the photographs on what he calls his “wall of death”; they were of grandparents, a father, and his adored sister—a beautiful young woman with a solemn, heart-shaped face, straight-backed in a simple long white wedding dress. Her daughter, Renée, looks exactly like her. Acoby’s uncle told me that the family worries about Renée, that they love her and wish her well.

We drove at sunset to the reserve’s graveyard, a meadow on the gentle slope of a small hill, encircled by bush, large spruce trees, and clusters of birch. The graves were marked by wooden longhouses, each with a small porch or opening where offerings could be laid. The grasses were long, with portions of the graveyard overtaken by shrubs, even trees. It was quiet, and the air was fragrant. There was a brief sprinkling of fine rain, even as the sun shone. Acoby’s uncle took me back through the brush to a longhouse with a faded blue, subsiding roof; there were small tokens by the opening, in memory of his sister, Renée’s mother. A few months later, Renée sent me the following undated poem, written in blue pencil:

There are times when I covet so much

The comfort inherent in a mother’s touch…

Infinite memory, suspended yet rushed;

Fleeting vulnerability… whispered, clutched.Freedom slips away every time I get near it,

Deprived of intimacy so long, I almost fear it;

The song of North Wind, I long to hear it…

I search for peace to still my transient spirit.