The Toronto Star is the best investigative newspaper in Canada. In recent years, it broke Jian Ghomeshi, Rob Ford, the ORNGE scandal, and numerous other stories. To their credit, editor Michael Cooke and publisher John Cruickshank clearly take this sphere of journalism seriously, and have ploughed millions into these investigations. (Lawyers’ bills alone are enormous for stories such as these.) Without the Star, Jian Ghomeshi might still be the host of Q, Rob Ford might still be mayor of Toronto, and Chris Mazza might still be running Ontario’s air ambulance service.

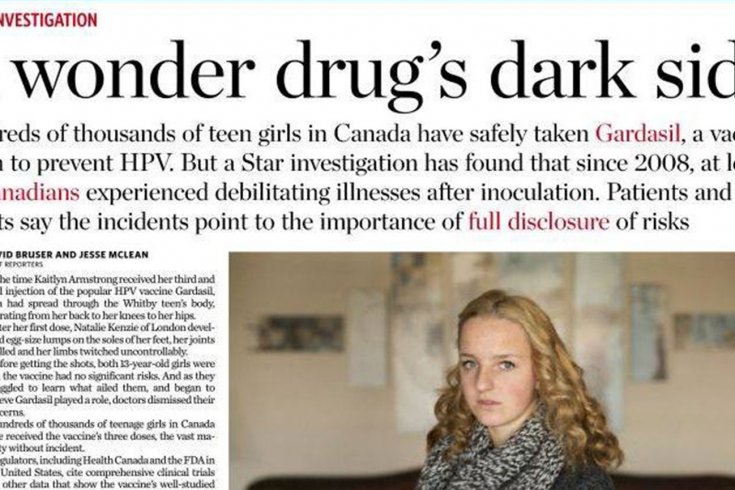

So it says something that even the Star could have botched a story as badly as it did on February 5, when it splashed a gruesome banner across its front page, entitled “A wonder drug’s dark side.” The drug in question—the vaccine Gardasil—is indeed a wonder drug. By preventing human papillomavirus infections clinically associated with deadly cancers (of the cervix, most notably), the vaccine can help save hundreds of Canadian lives every year—not to mention many tens of thousands of lives around the world.

But that was not the focus of the Star’s story. Instead, reporters David Bruser and Jesse McLean zeroed in on a small group of vocal patients, family members, and activists who claim—without evidence—that Gardasil injections cause a range of severe medical problems. As noted by many prominent critics from within the medical community (including a long list of well-credentialed medical professionals, whose powerful letter to the editor was published in the Star almost a week later), the article is grossly misleading. General statements about the tested safety of the vaccine are embedded obscurely, while the horrifying tales of death and disability are splashed prominently throughout, including a huge photo spread. Any casual lay reader exposed to this article would have come away with the impression that this vaccine is dangerous.

The article is breathless and misleading—the Star letter writers argue—because the reporters who wrote it, and the anti-vaccination sources they relied upon, have no grasp of the difference between correlation and causation. It’s precisely the same error that many anti-MMR-vaccine activists make: the onset of symptoms associated with autism sometimes can coincide with standardized pediatric vaccination schedules, but that does not mean one causes the other.

As with the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine, the HPV vaccine has been the subject of enormous epidemiological study. Almost 170 million doses have been administered worldwide. One of the largest studies of the drug’s safety was funded by national governments (Sweden and Denmark)—not drug companies. It found no increased risk of autoimmune conditions, neurological diseases or blood clots, the most commonly alleged medical harms claimed by HPV vaccine opponents.

On the other hand, who is going to focus on these sort of dry statistical studies, when you can go to the Toronto Star and get vignettes like this?

One [girl] needed a wheelchair, another a feeding tube. A 14-year-old Quebec girl, Annabelle Morin, died two weeks after receiving the second injection of the vaccine. It was 7:30 p.m. on the night of Dec. 9, 2008, when her mother, Linda, found her in the tub, her head underwater and turned to the side. The paramedics lifted Annabelle’s body on to a stretcher. “I put a blanket on her, saying, ‘She’s going to freeze,’ ” Linda recalled. “I did not know she was already dead.”

That is a heartbreaking story—so heartbreaking that it destroys the ability of most readers to rationally assess the statistically proven risk of dying from taking the HPV vaccine, which is zero.

Anti-vaccine activists will claim that such articles simply provide “balance” in a media environment otherwise dominated by journalists (like me) who rely on government bodies, respected academic studies, and public-health experts. But the media’s obligation to present balance applies only when there is a genuine controversy in the mainstream, peer-reviewed scientific literature. That is not the case here. On CBC Radio, Dr. Yoni Freedhoff called the Star story “one of the worst examples of false-balance journalism I’ve read.”

One possibility is that the Star reporters in question—Bruser and McLean—knew all this, and wrote it up anyway. If so, that would be journalistically unconscionable. Under this theory, the two reporters would have knowingly published a story whose effect would be to discourage Canadians from taking potentially life-saving medication that carries no proven risk. I would never level that charge against journalists without proof.

Instead, I prefer to assume that the pair simply don’t understand science or statistics. Nor did their assigning editor, or any of the other editors who worked on this massive front-page piece. From my experience in a newsroom, I’d estimate that at least half a dozen senior editorial staffers would have read such a legally sensitive piece before its publication.

And there is the real scandal here. None of those people had the basic scientific literacy to know that what they were putting on the front page of Canada’s biggest newspaper was misleading tripe. And we are not talking about quantum physics here—but rather the basic, high-school science-class principle of cause and effect. That’s pathetic.

The Star’s reaction to the whole affair comprises a second scandal—this one having nothing to do with scientific ignorance, but rather with ass-covering organizational-behaviour reflexes. Soon after the front-page story appeared, several medical professionals posted rebuttals on social media. Prominent among them was Dr. Jennifer Gunter—a board-certified OB/GYN, and a recognized expert in vulvovaginal disorders. (“One of my specialties is treating women with autoimmune conditions of the vulva and another is treating vulvar pain and pain with intercourse for women who have had surgery and/or radiation for cervical, vaginal, and anal cancer due to the human papilloma virus,” she recently wrote—so yeah, she’s got this one.) Earlier this week, this website reposted an essay by Gunter that put the entire Star newsroom on notice of the page-one fiasco. The paper’s response? Heather Mallick, a Star columnist who tells readers she is “trying to teach myself about statistics and science so as to find a way through the fog” slagged off Gunter as a mere “rural doctor.” Meanwhile, when health reporter Julia Belluz called Star editor Michael Cooke for comment, he dismissed her as a Gardisil shill. (Belluz’s chronology of these events, published at Vox.com, is worth reading.)

Yesterday, someone from the Star finally manned up and admitted that it was the newspaper—not some “rural doctor”—that was in the wrong. “We failed in this case,” Cruickshank told CBC Radio host Carol Off on As It Happens. “We let down. And it was in the management of the story at the top. . . . It’s especially troubling that the treatment was in that way during this period that there is an extraordinary debate over inoculations, frankly, between science and nonsense. And we have, at this newspaper, always been on the side of science.”

Well said, Mr. Cruickshank. Better late than never. (Oh, and we’re still waiting to hear directly from Mr. Cooke.)

The overarching problem, of course, is that everyone in the mainstream media says they’re “on the side of science.” But what this episode shows is that there are precious few journos who actually understand what science is.

Maybe the next hire at the Star should be someone with a degree in the health sciences. Someone with the credentials of—oh, I don’t know—Dr. Jennifer Gunter? And if they used Mallick’s salary to fund the position, you wouldn’t hear any complaints from me.