Shannon, the teenage heroine of Marjorie Celona’s debut novel, Y, is a “short weirdo with a bum eye,” a cross, she says, between Shirley Temple and a pug. Physically underdeveloped, she is cripplingly insecure but admirably resilient. All she knows about her origins is that she was left as a baby, wrapped in a dirty sweatshirt, by the glass doors of a Victoria YMCA.

She spends the first years of her life subjected to abuse and neglect in foster care, passed from home to home, sharing a bunk bed with a smelly bedwetter, and being called the wrong name by parents with more kids than they can manage. Then Miranda, a caring but flawed single mother, miraculously adopts Shannon at the age of five. In this stable home, the girl yearns to reconcile the unanswered questions of her beginnings: who is her birth mother, and why was she abandoned?

Shannon’s newly acquired sister is Lydia-Rose. Half a year older, she is, by contrast, a classic beauty, tall and skinny, with honey-brown skin and copper-coloured hair. She falls into the role of Shannon’s imperfect protector and teacher, backing her up in schoolyard fights and sharing stories about the aggressive desires of boys. Shannon watches Lydia-Rose’s exploits with jealousy and awe.

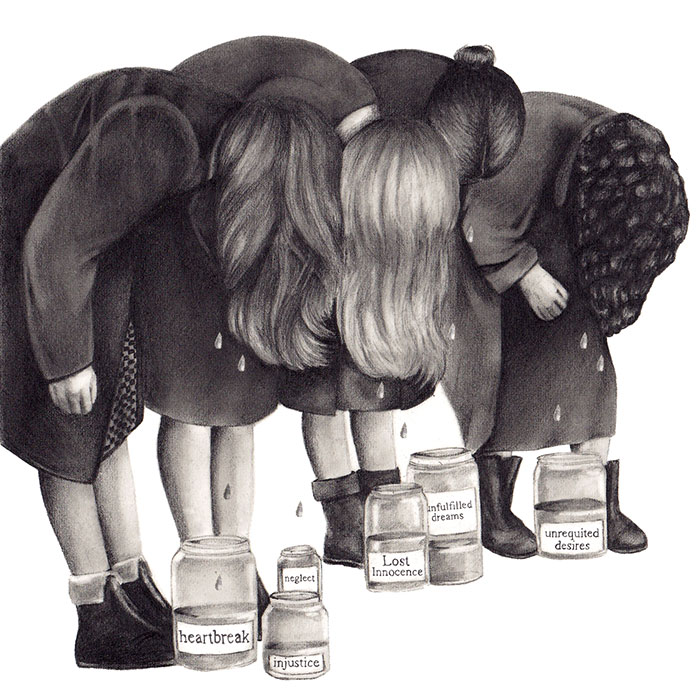

An accomplished and heart-wrenching story, Y is a modern variation of the archetypal coming of age tale. It joins a long list of novels that depict the transition from girl to woman as a painful trudge of rejection, violence, self-loathing, and narrow options. While the male Bildungsroman , such as Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Catcher in the Rye, or The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, tends to involve the acquisition of power, the experience of adventure, or the act of rebellion, the female version seems dictated by how well a heroine can withstand suffering without flinching.

The thread of young women’s survival runs through many CanLit coming of age favourites, such as Ann-Marie MacDonald’s Fall On Your Knees, Margaret Laurence’s The Stone Angel, and Camilla Gibb’s Mouthing the Words. In classic tales and gritty contemporary fiction alike, girls are victims—of female bullies, of predatory father figures or absent mothers, of limited circumstance. The specifics may have changed, but the fate of the heroines has not.

Anne Shirley is the plucky red-headed idol of our collective youth. The first of the Anne of Green Gables novels was published in 1908, and since then L. M. Montgomery’s bestselling series has been translated into more than a dozen languages; been adapted into multiple films and television programs; and spawned a flourishing tourist industry in Prince Edward Island. Yet despite the rosy glow around Anne’s story and our national obsession with it, the girl begins her narrative journey unwanted and rejected because of her sex.

Anne is orphaned as a baby when her parents die of typhoid fever. She spends her childhood in institutions, and in the homes of strangers, where she is treated more like a servant than a child. When she reaches adolescence, she is adopted by Marilla and Matthew Cuthbert, middle-aged siblings looking for a boy to work their farm. When the girl is sent to them by mistake, Marilla insists that she be returned, but Anne’s desperation eventually leads her to relent.

Anne is incorrigible and prone to amusing misadventures: dyeing her hair green, getting her best friend drunk, and finding herself in a sinking boat while re-enacting a Tennyson poem. But she is also whip smart and studious, and she wins the prestigious Avery Scholarship, which will send her to teachers’ college.

Toward the end of the novel, however, Matthew, whom Anne regards as a “kindred spirit,” dies of a heart attack after learning that the family has been bankrupted. Just before his death, he tells her, “I’d rather have you than a dozen boys, Anne… I guess it wasn’t a boy that took the Avery Scholarship, was it? It was a girl—my girl—my girl that I’m proud of.” And here is the book’s cruel twist: Anne’s devotion, her eagerness to please, culminates in her giving up the scholarship. Instead, she stays on the farm to tend to Marilla.

“We pay a price for everything we get or take in this world,” Montgomery writes in the novel. “Although ambitions are well worth having, they are not to be cheaply won, but exact their dues of work and self-denial, anxiety and discouragement.”

Later coming of age tales go even further in underscoring this theme, most notably Alice Munro’s 1971 novel Lives of Girls and Women. Set in the 1940s, in the rural Ontario town of Jubilee, the book follows Del Jordan from late childhood into adolescence. A self-professed outsider, Del is bright and ambitious, and too big for the boundaries of Jubilee. Men play supporting characters in the book, but Munro uses Del’s attractions to them as obstacles to her success. As with Anne, Del’s circumstances (this time the consuming love for a man) lead her to lose the scholarship that would aid in her escape.

Each story in Munro’s cycle situates Del in a new crisis: embarrassment about her mother, awkwardness over her emerging sexual desire, her fear of domestic submission, death, and loss. The book acts as a feminist interpretation of how the trials of growing up ambush gifted girls on their path to freedom.

Similarly, Margaret Atwood’s Cat’s Eye , published in 1988, tells the story of successful painter Elaine Risley, as she reflects on the painful relationships of her childhood and teenage years. These experiences of cruelty have heavily influenced Elaine’s adult life and her art, and Atwood explores the construction of female identity, and conveys a keen-eyed feminist perspective on what it means when other girls, quite literally, leave you out in the cold.

As Atwood depicts it, a woman’s character is built by pushing up against pain and remaining upright. Girls savagely betray each other, but also lead each other to moments of understanding and growth. In one of Elaine’s recollections, her young friend Carol pulls up her skirt and pulls down her underwear to reveal the marks of her father’s belt buckle where he has beaten her; the display gives her new authority among her friends. Afterwards, she shows them the wet spot in her mother’s bed, and leads them in a semi-nude game of patient and nurse. For Atwood, expertise is obtained in these ugly, clandestine moments.

In earlier books, the travails faced by the heroines are consistent with the constraints of less enlightened times. In contemporary novels, however, while girls and women have more freedom, their misery persists in even more harrowing and disturbing circumstances. Take Rebecca Godfrey’s The Torn Skirt , published in 2001, in which sixteen-year-old Sara, suddenly fatherless, learns that her boyfriend and his friends have gang-raped a local girl with a garden hose.

Meanwhile, in Heather O’Neill’s 2006 novel Lullabies for Little Criminals, winner of the Canada Reads competition, the young heroine, Baby, navigates a similar terrain of sexual cruelty. Baby is motherless, resigned to propping up the addictions of her wayward father. She is eventually taken by social services and placed in a foster home while her father is sent to a rehab centre. Baby becomes a runaway, is locked in a juvenile detention facility, and later seeks stability and a semblance of love in the arms of a pimp.

Little, the protagonist of Amber Dawn’s 2011 Lambda Literary Award–winning novel, Sub Rosa, is yet another teenage runaway and prostitute. In this surreal fairy tale, Little becomes a reluctant hero and a leader in a battle against an outside force that seeks to destroy her underworld community.

Collectively, these books examine the darkest corners of female experience, highlighting young women’s lack of power, regardless of era or circumstance. There is an ambivalence about female agency that sets up girls, fictional or not, as perpetual victims. In many cases, this theme mimics reality: O’Neill’s novel draws on the details of her own hardscrabble childhood, while Godfrey also wrote Under the Bridge, a true-crime account of the 1997 death of Reena Virk, a fourteen-year-old girl from Saanich, BC, who was beaten and killed by a group of teenagers.

Into this terrain of hopeless, exploited children enters Y’s Shannon, another abandoned girl on a treacherous course toward womanhood. Considering these books as a whole, Lydia-Rose’s response to Shannon’s question of why she would have sex when she didn’t want to is particularly weighted. “You are a stupid freak sometimes. Grow up,” Lydia-Rose sneers, indicating that she has already done so, and that suffering is the means to coming of age.

In one revealing scene, these two very different girls represent specific brands of girlhood experience. Shannon spends an evening at home with a head cold, drinking NeoCitran, wearing flannel pyjamas, and reading Judy Blume books. After midnight, Lydia-Rose returns from a party she went to with a boy she has a crush on and climbs into Shannon’s bed.

Lydia-Rose is wearing bubble gum pink socks and flared jeans, and she lifts her sweater to reveal a new purple satin and black lace bra. Shannon notices a long red welt on Lydia-Rose’s stomach; she asks where it came from and traces it inquisitively with her finger. Lydia-Rose explains, “He said it would be fun… If we did it rough.”

Shannon does not react with disgust, rage, or even protectiveness. Instead, she’s envious, and dismayed that she doesn’t inspire this kind of talk and coercion. “I don’t radiate sexual,” she thinks. “I could stand on the corner in a nightie and spike heels and men would walk on by.”

Marjorie Celona offers this vivid tableau littered with visual markers of childhood—its books and magazines, its girlish and gauche costuming—combined with Lydia-Rose’s violent loss of virginity. After her revelation, Lydia-Rose reads aloud to Shannon from a book about New York performance artist Marina Abramović, pointing to a picture of the artist dressed in crotchless leather chaps. She tells Shannon about a piece in which Abramović invited people to do whatever they wanted to her. The reference to 1974’s Rhythm 0 is not accidental; the artist endured six hours of humiliation from her audience via seventy-two implements, stating when it was over, “I felt really violated: they cut up my clothes, stuck rose thorns in my stomach, one person aimed the gun at my head, and another took it away. It created an aggressive atmosphere.”

This performance is one of Abramović’s best known, and it arguably cemented her reputation. Suffering, it seems, is the mark of female success.

Anne of green gables concludes with a complacent surrender. “Anne’s horizons had closed in,” Montgomery writes, “but if the path set before her feet was to be narrow she knew that flowers of quiet happiness would bloom along it.” It is an all too familiar lesson in sacrifice, and the ever-optimistic Anne looks forward to the next “bend in the road!”

Coming of age stories have changed little in the hundred years since. While Y’s rough terrain is far from the idyllic backdrop of Anne’s Green Gables or Del’s Jubilee, Shannon has learned a similar lesson as her forebears did. (CanLit is, of course, not the only place these trials exist. Similar themes emerge in American and British novels, such as Sapphire’s Push, which was adapted into the film Precious, and Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit. Y succeeds precisely because it unflinchingly explains what we already know from literature and life: girls still grow up to learn that loss and pain are essential to becoming an adult.

In the girlish bedroom that Celona so artfully creates, Shannon is overwhelmed by Lydia-Rose’s confession and the nonchalance of her impromptu art book reading. Her reaction is to lock herself in the bathroom and carve a star into her calf with a knife. This self-punishment brings her comfort, as though it gives her the credibility that Lydia-Rose earned through her brutal sexual experience. When Shannon returns to the bedroom, Lydia-Rose tells her, “He didn’t know it was my first time. I never want him to know.”

As with Abramović’s disturbing performance, these girls do not triumph over, conquer, or even fight against pain, but instead prove themselves by simply enduring. When tragedy or injustice befalls our real and imagined heroines, it is their burden to bear, their inevitable, unspoken formulation of identity. The world is an anvil upon which the narrative shapes girls such as Shannon into blades.

This appeared in the October 2012 issue.