Pierre Poilievre first came to my attention in 2004, when we were both new to Ottawa and I used to sit in the gallery of the House to watch Question Period. Poilievre, then a freshly elected twenty-five-year-old, stood out as unusually combative. He sought every opportunity to take cheap shots at his opponents, like a trash-talking hockey player, always slashing, trying to draw penalties. He would often deliver over-the-top partisan rants typed up by brash, young PMO staffers. I found his harsh recitations chilling because he gave the impression he would deliver the attacks no matter what the words said, so fierce and remorseless was his partisanship.

But his skill and zeal made him a valuable player, and once Stephen Harper beat Paul Martin in the 2006 election, he made Poilievre parliamentary secretary to John Baird, the president of the Treasury Board. In 2013, Harper made him minister for democratic reform and put him in charge of overhauling the Fair Elections Act. Opposition parties and civil society groups thought the new bill would weaken Elections Canada’s enforcement arm and make it harder to vote, a milder version of Republican-style voter suppression measures. When Elections Canada head Marc Mayrand complained he hadn’t been consulted and warned the amendments could hamstring the agency, Poilievre attacked him by implying he was a Liberal. The “referee should not be wearing a team jersey,” he said, a statement calculated to weaken public faith in the independent agency that runs Canadian elections, one of the best in the world.

After the Liberals won in 2015, Poilievre blossomed as a critic, finding ways to hold the government’s feet to the fire and tormenting Bill Morneau with particular relish. He pressed Morneau on the blind trust in which he had placed shares in the family pension management firm while he was making rules about the industry. When Morneau bent to pressure and divested, Poilievre went for the jugular. “The finance minister hid his offshore company in France until he got caught, and then he reported it. He hid from Canadians his millions of dollars in Morneau Shepell shares in a numbered company in Alberta, despite wrongly telling others it was in a blind trust, until he got caught, and now he is selling them.”

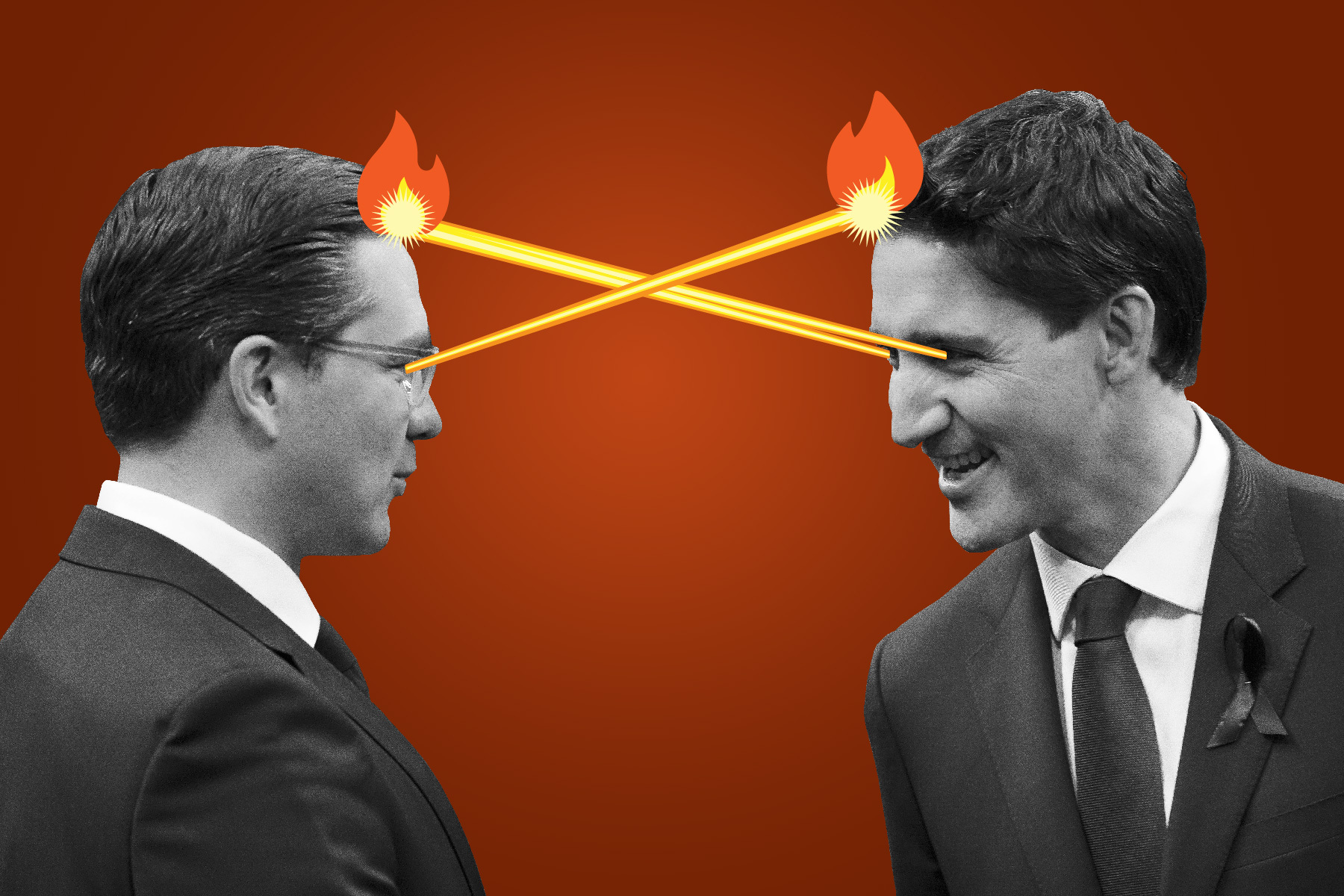

Poilievre has a gift for quickly finding the most devastating line of attack and is thoroughly committed to the Conservative cause, qualities that earn him grudging respect from his opponents, including Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. During the WE Charity controversy in 2020, when Trudeau testified by video hookup at committee, Poilievre roasted him over the speaking fees WE paid his family members, demanding he say the amount. When Trudeau refused, saying he didn’t have the number in front of him, Poilievre was scathing. “Nobody believes you,” he said. Trudeau actually squirmed in his seat as Poilievre skewered him, and he tried to talk about his mother’s advocacy work. Poilievre was not interested. “You don’t know how much your family has received from this organization to which you tried to give a half billion dollars. Really?”

A friend talked to Trudeau the day after Poilievre won the Conservative leadership in 2022—and did it with 68 percent of the vote on the first ballot—and reports that the prime minister was “energized” by the prospect of facing Poilievre in an election. Poilievre campaigned as an outsider who wanted to undo Trudeau’s Canada. He promised to get rid of mandates, defund the CBC, and fire the governor of the Bank of Canada. “He thinks that Poilievre is everything he dislikes,” says another friend, referring to Trudeau. “He’s an asshole. He’s mean. He’s gonna hurt a lot of people who are already vulnerable. He can’t stand him.”

But it is not clear to Liberals, even some close to Trudeau, that he is the best candidate to face Poilievre. Some think he is uniquely qualified to lose to him, given the deep resentment and fatigue that many voters feel for Trudeau—and the dominance of cost-of-living concerns, which have destroyed many a government. But the two candidates are evenly matched in one regard: mutual hostility. This may turn out to be one of the meanest elections in recent memory.

The hostility is clear enough in every exchange between the two men. Two weeks after winning the leadership, Poilievre took the fight to Trudeau in the next Question Period, showing his ability to find the weakest spot in an opponent’s armour. “It is good to see the prime minister here, visiting Canada, to fill up the gas on his private jet,” he said. Trudeau had just flown back from Queen Elizabeth’s funeral in London and the UN General Assembly in New York and was about to fly to Japan for the funeral of former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe. Poilievre pressed him on the impact of the carbon tax on home-heating oil in Newfoundland and Labrador, which was going to hit seniors on fixed incomes hard. “The leader of the Liberal Party has an opportunity to respect the fact that heating one’s home in January and February in Canada is not a luxury, and it does not make those Canadians polluters. They are just trying to survive. This from a prime minister who burned more jet fuel in one month than twenty average Canadians burn in an entire year. Will the prime minister ground the jet, park the hypocrisy, and axe the tax hikes?”

Trudeau responded by mocking Poilievre’s support for unregulated cryptocurrency. “If Canadians had followed the advice of the leader of the opposition and invested in volatile cryptocurrencies in an attempt to ‘opt out of inflation,’ they would have lost half of their savings.”

In retrospect, Trudeau might have been better off taking Poilievre’s suggestion on the carbon tax. Under the threat of losing Atlantic seats, in October 2023, Trudeau agreed to let his finance minister, Chrystia Freeland, suspend the carbon tax on heating oil for three years, overruling objections behind the scenes from environment minister Steven Guilbeault. Politicians in the rest of Canada, whose constituents would not get a break on natural gas, objected angrily. It looked like desperation, stoked regional resentments, and threatened to undermine Trudeau’s central environmental policy. If he had acted sooner, he might have been able to change the policy without a humiliating backdown that undercut the rationale for the carbon tax.

Trudeau won in 2015 after campaigning to take action to help the “middle class and those working hard to join it,” convincing Canadians that he, not Harper, would be more likely to look after their economic interests. At some point, the government stopped emphasizing that. Liberals can point to significant ongoing efforts to help people who are struggling, through child care and dental programs, for instance, but the government has stopped talking effectively about its commitment to the middle class. They did not see the cost-of-living crisis coming.

On the economy, Poilievre has been strong, overmatching Trudeau with a libertarian message delivered skillfully on social media. Once he dropped his crypto fixation, Poilievre had a good, simple message: the government should get out of the way, cut taxes, and go after “gatekeepers” stifling growth in other levels of government. “There are people in this country who are just hanging on by a thread,” he said in his victory speech. “They don’t need a government to run their lives; they need a government that can run a passport office. They need a prime minister who hears them and offers them hope that they can again afford to buy a home and a car, pay their bills, afford food, have a secure retirement, and, God forbid, even achieve their dreams if they work hard. They need a prime minister who will restore that hope, and I will be that prime minister.”

Poilievre exaggerates the economic impact of the carbon tax to the point of dishonesty. Most voters are better off for it because they receive bigger rebates than they pay in tax, but they notice only the increased bills, not the rebates. And in the symbolic sense in which voters absorb politics, Poilievre is right in a way. Trudeau has made decisions that have constrained resource extraction—mining, oil, and gas in particular, but also agriculture and transportation—and imposed restraints on sectors of the economy that would have grown faster if, say, Harper had continued as prime minister. Under Trudeau, it has become harder to build pipelines or mines. In response to climate, public health, and Indigenous concerns, Bill C-69, which critics call the no-more-pipelines act, opened new barriers for projects in these sectors. Conservatives were particularly angered that the bill required regulators to consider the possibility of violence against Indigenous women from the “man camps” that are established wherever resources are extracted, seeing it as an insult to the men who hew the wood and draw the water we all need.

For leaders trying to create economic opportunity for their people, Trudeau’s policies were unbelievably frustrating. “I just think he’s been the most divisive prime minister we’ve ever had,” says former Saskatchewan premier Brad Wall. “More so than his father, even. I think his policies are more of a danger to the West’s economy, and willfully so.” Wall questions the sustainability of the federation. “This Canada, it doesn’t really represent us in a meaningful way, or doesn’t provide us remedies when we feel like we’re just being ignored or, worse, targeted. And I didn’t think that was the sense during [the] Chrétien and Martin [administrations]. I mean, they were pragmatic, they were fiscally responsible, they had to support and promote a Canadian industry, including oil and gas.”

Despite western alienation, the environment and energy file is not the worst one for Trudeau or the best one for Poilievre. As always, bread-and-butter issues are the easiest way to get the attention of voters, and both bread and butter have become much more expensive while Trudeau has been prime minister, with annual food inflation pushing 10 percent—the result of the war in Ukraine and pandemic supply chain issues. But Poilievre has been able to blame it on the carbon tax—a real but small factor in price increases—and on inflation caused by the government’s free-spending ways.

Federal policy may or may not be responsible for inflation—which is worse in other countries than in Canada—but there is little doubt that the Trudeau government is responsible for the housing crisis. Federal governments have historically helped build housing during times when supply was tight, and Trudeau did not take the necessary action, even while increasing immigration to record levels—431,645 newcomers in 2022. There was nowhere for all those new people to live. And no place for the 551,405 international students Canada welcomed in 2022, plus an unknown number of undocumented foreigners—the migrants who somehow got into Canada without papers. Tent encampments started to appear in major cities, not only for the people afflicted by mental health issues or addiction but also for those who could not find a place to rent. And forget about buying: home ownership is for baby boomers.

Although this crisis should have been foreseeable—that’s why we have the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Statistics Canada—it seemed to come as a surprise to the Trudeau government. That created a huge political opening for Poilievre. “I think we’re headed to a massive socioeconomic crisis in the next couple of years as an entire generation of young people are forced to give up on having kids, building home equity, or even leaving their parents’ basements,” he told the Sault Star in July. “It was never like this before Trudeau, and it won’t be like this after he’s gone.”

Poilievre was speaking for all the people stuck in their parents’ basements, and they were listening. Trudeau had somehow failed to see this issue coming. His government had actually started putting money into housing—more than any prime minister since Brian Mulroney—but it was not enough to keep up with demand. Young people began to tell pollsters they planned to vote Conservative. This was an enormous shift from recent patterns and an existential threat to the Liberals, who had looked like the party of hope and change in 2015. Now, it was Poilievre who was talking about hope—and young people who were listening. Underpinning the loss of support was a generalized gloom among the young, who got the dirty end of the pandemic stick and now can’t find places to live.

“The most pessimistic group are young people,” says pollster Nik Nanos. “In the past, young people tended to be the most optimistic, which means that, in 2015, for a leader that talked about sunny ways and appealed to young people, now he has taken that generation and turned them from the most optimistic and hopeful into the most pessimistic and negative when it comes to the country and when it comes to the future.”

And the gloom was not confined to young people. In November 2023, pollster Frank Graves did a survey and was shocked by the grim national mood. Seven out of ten Canadians felt the country was moving in the wrong direction, the worst score Graves has seen in thirty years of polling. Three quarters thought the world was becoming more dangerous. And not even half said they had a strong connection to Canada. Canadians were increasingly distrustful of institutions, worried about political polarization, disinformation, and their own finances, and increasingly skeptical about immigration. “When you look at the collective expression of fundamental barometers of societal health and cohesion, this constitutes a legitimacy crisis,” says Graves. “It’s not sustainable.”

When it is time for a change, it is time for a change. At the end of 2023, the polls kept sending Trudeau the same grim message, and everything the Trudeau government did seemed to go sideways. “It’s like watching somebody who’s been on the ice too long,” says one former senior staffer. “It doesn’t matter how good of a hockey player they are. If they’re gassed, they’re gassed, and they’re just not able to do anything.”

The next election is Poilievre’s to lose, but he might find a way to do that. He is insulting to reporters and friendly to anti-vaxxers. There is a sensible plan behind this stance. If he can permanently absorb supporters from Max Bernier’s People’s Party of Canada, the Conservative Party will not have to worry about its right flank in every election. But would middle-of-the-road Canadian voters find his openness to outlandish ideas off-putting? Would voters really want to entrust the management of the national economy to someone who could be gulled by the hucksters selling crypto on YouTube?

Maybe not, but by the time Poilievre won the leadership, many Canadians were exhausted with the current prime minister. He had pulled off an election victory by polarizing voters around the pandemic, but frustration with him was growing. People who had never voted for Trudeau were increasingly unable to abide pious lectures about diversity from Prime Minister Blackface or about feminism from the man who threw Jody Wilson-Raybould under the bus. Worse, people who had voted for him repeatedly were tired of his schtick. “Every MP will tell you that their closest, most long-standing Liberal supporters all think it’s time,” a Liberal MP told me in late 2023. “Every MP.”

Even his friends were telling him to go. “I think of him more as the leader for a time, and I think the times require a different kind of leader now,” says one close friend. “That’s how I look at it.”

Governments naturally take special care to look after people in their electoral coalition—preferential treatment that, over time, becomes increasingly irritating to those outside that coalition. Trudeau looks hostile to rural people and those who make their living in resource extraction. He rarely makes appearances with police or members of the Canadian Armed Forces, and he doesn’t speak often or effectively about issues that matter to working-class white men. His diverse, social-media-attuned staffers take pains to be politically correct, but a growing number of people outside his coalition think that the government ignores issues that are important to them. He has focused, perhaps by necessity, on the people in his coalition—and left the rest to Poilievre.

But Trudeau does not want Poilievre to run the country. “He’s been around this place a long time,” Trudeau recently told me. “I have never seen the drive to service. What is the call to build a country? I’ve seen a tremendous, cut-throat competitor, someone who’s willing to do whatever it takes to win, to score points, to make the goal. And there’ve been politicians in all parties who do that, but that’s never been what drives me.”

Trudeau is telling everyone he is keen to face Poilievre in an election. “I just see it as such a fundamental choice in what kind of country we are, who we are as Canadians,” he told me. “That, for me, is what I got into politics for: to have big fights like this about who we are as a country and where we’re going. And that is what this next election is going to be—because the contrast between the vision that Mr. Poilievre is putting forward and what we continue to work for every single day couldn’t be clearer, couldn’t be crisper. As a competitor, as a leader, as someone committed to this country, being there for that conversation with Canadians touches me at the core of what I feel my purpose is in stepping forward into politics.”

But voters struggling to pay their bills do not believe that Trudeau understands their problems, and Liberals have been watching in dismay as the government has failed to connect on bread-and-butter issues. If there was a strong leader waiting in the wings, Trudeau would have to watch out for knives in his back.

There are no similar mixed feelings among Conservatives. They have rallied behind Poilievre, setting aside any squeamishness as he has shown greater poise and depth and continued to expand his lead in the polls. He is doing so well, and has been for so long, that he is attracting prominent prospective candidates, as Trudeau did before the 2015 election.

And Jenni Byrne, the formidable strategist and organizer who helped Harper win his majority in 2011, is his chief adviser, bringing her focus, skill, and determination to his operation. She knows her candidate well, and neither of them will shrink from doing what is necessary to win.

Excerpted from The Prince: The Turbulent Reign of Justin Trudeau by Stephen Maher. Copyright © 2024 by Stephen Maher. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster Canada, Inc. All rights reserved.