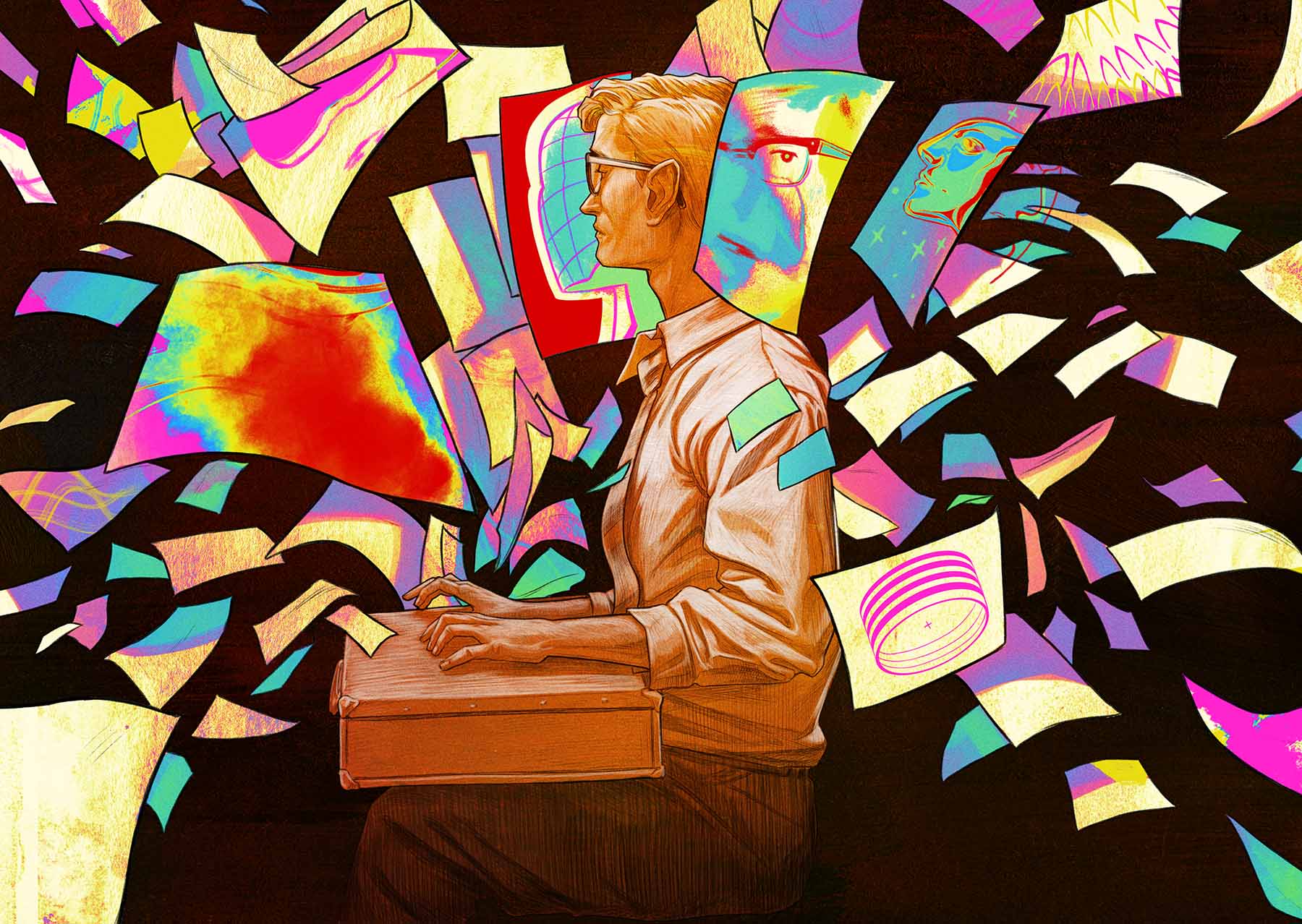

There are numerous drafts. Some parts are written in pencil, some in pen, some on a typewriter, and some on a computer. Several pages were printed on old-timey paper attached to each other along a perforated edge, unfurling like a scroll, and some were saved on a 3.5-inch floppy that can now be retrieved only as a file of randomized numbers, like code in the Matrix.

The progression of technology seems to imply a hierarchy of edits—that the pencil draft is superseded by the pen draft, the typewritten pages supersede the longhand ones, and the perforated paper supersedes them all. However, scenes rarely appear in more than one edition, meaning that each ensuing draft was more addition than revision.

Everything is unstapled; pagination happens randomly and redundantly. “Page one” repeats like déjà vu. There are notebooks labelled “The Fortress Before Armageddon” or “Origins Pt II: Plus Messiah’s Speeches” or “THE WAR” (emphasis in original), but it is impossible to discern sequence. There’s a typewritten stack, bound by a paper clip, that is titled “CHAPTER” but without any ensuing number; and beside it, in demonstrative red ink, is written “DONE.” There’s a folder labelled “OUTLINE.” It is empty.

There is orphaned loose leaf; there are algebraic formulas; there are hand-drawn character sketches. The point of view veers between third and first. Sometimes it takes the form of a memoir; sometimes it’s epistolary; sometimes there is what one would call poetry.

The narrative itself takes place across several books, over multiple generations, on several astral planes. There is a timeline of reality, which begins as a straight shot but then pivots into cubes that stack upon themselves. One scene is dated 1982, another is dated 2500 AD, and another features a knight with a sword. The cast includes Jesus, Plato, the Buddha, and Descartes. There’s also this guy named Garner, who seems central to it all but is not to be confused with another character named Ganor.

There is a pyramid. There are dog fights. There is Heaven and there is Hell and they connect at Drumheller, Alberta. There is a Golden Web (always capitalized). There is an astute knowledge of what to do during a bad LSD trip.

There is one notebook (the thickest) that ends with the declaration, “If this is true, it has only happened a few times in the history of life itself. It has marked a turning point both here and on earth.” But at the bottom of that final page—of a scene that seems earmarked for epiphany—there is a concluding footnote: “Continued in previous section.”

All of this—the notebooks, the loose leaf, the worlds—is gathered in the briefcase. The paper is brittle in the open air, and such frailty gives each sentence a sacred weight. Because with every storming of a castle and boarding of a starship, with every flourish of calligraphy and strikethrough of red pen, there is an unspoken yet deafening declaration: I will write a story, and I would sooner die before I let it be incomplete.

Eight years ago, my mother met a woman named Laurene. When my mother told her she had a son who was a writer (I hate it when she does this), Laurene exclaimed, “I have a story for him!” And Laurene, I came to learn, meant this in the most literal sense.

Two weeks later, in her kitchen, Laurene told me her late husband, Jim, had spent decades writing a novel that he had always planned to finish upon retirement but died before he got the chance. He was not a professional writer, rather a surveyor by trade. Laurene presented me with a large leather briefcase, heaving it onto the table and resting both hands upon the lid. “His notes, his chapters, his everything is here.”

She summarized the plot for me. (My takeaway, in essence: reawakened inhabitants of the universe’s peripheral dimensions organize a primeval army in order to save the Earth.) But, she said, the ending was still undetermined.

“Do you want me to proofread it?” I asked.

“I want you,” she said, “to finish it.”

As Laurene slid the briefcase toward me, her eyes shone like she was giving a great gift. I assumed she felt she was handing over an easy fortune because the hard part was already over—the labour of birthing an idea—and all I had to do was towel it off and spank a bit of life into it. So how to explain to her that right then and there, sitting in her kitchen as she told me of her late husband’s life’s work, even as I accepted the briefcase, I knew I would never add a word to the story? How to convey to her that I had neither the temerity nor the tenacity to write about a world that could be saved? How to break it that there was no hope?

I accepted the briefcase because I was polite and uncomfortable, too embarrassed for both of us to decline. But there was another thing: a vague yet implacable connection I felt to Jim, that I ought to care for him the way I would for myself, because in that moment, the two of us seemed much the same, separated only by age. At that time in my life, I was at a fulcrum in my career: all the glitz of writing—its shining promises—had rubbed off, and what remained was a knowledge of the unnavigable distance between where I was and where I wanted to be. As a novice writer, I had thought that once I began to publish, the route would prove easier. But the exact opposite had happened. It was only when I began to publish—and witnessed the immediate irrelevance of it—that I understood the impossibility of my ambitions. The briefcase seemed to know this too, having learned it in defeat.

Later that night, as I sat in the blue light of my laptop screen while a Word document’s cursor blinked back at me, I flipped up the clasps, and the briefcase’s hinges creaked open. Inside were thirteen notebooks, a stack of legal pads, ballpoint pens, a floppy disk, and piles of paper, yellowed with time. The headlights from a passing car poured through the window and across my shaking hands.

I laboured through the drafts, and the hours rubbed against each other like knives being sharpened. “So this,” I said to the briefcase, “is what it means to be a writer.” How paltry and vain, how arrogant in the face of inadequacy. I closed the briefcase, vowing to never open it again.

But I did not abandon it. Spanning eight apartments and two provinces, I have kept the briefcase with me, stowing it snugly into each bedroom closet, behind the laundry basket and beneath the violin I never play.

I have considered throwing it out, tossing it into a Goodwill drop-off. But then there’s the image of all that loose leaf tumbling in the updrafts of the recycling depot. Because to forsake the briefcase would be to admit the expendability of writing, and that, in time, a similar destiny awaits me.

For the better part of a decade, I had believed Laurene’s request unique. But, as the cliché goes, every story has already been told.

“People ask me to do this all the time,” the editor of this very essay told me when I first explained my situation. “Everyone is either filling a briefcase themselves or trying to get somebody to empty their briefcase. And when people find out you’re a writer, they know which one you are.”

A reporter I know concurred. She told me of serial requesters, of email blasts that begin “Dear Esteemed Writer.”

“You’re not special,” she told me.

A third writer disagreed but only on a level of semantics. “Everyone’s special,” he said, before telling me about the epidemic of ghostwritten biographies. “My Presbyterian grandmother, who believed that none of us are special, would have been appalled.”

But I contest that the fact the briefcase novel is just that—a novel—separates Laurene’s request from the chaff that clogs up an inbox. This was not a pitch for a story, or a fragment thereof. It was worse. It was an entire story—just a few wormholes in the narrative, and all I had to do was step into them and chart their course.

Writing a story, no matter the length, requires obsession. It is the only emotion that can withstand the tedium. And so the act of adopting someone else’s story—no matter how trivial or fictional—is revealing for not only the one who proposes but for the one who accepts. Because amidst the onslaught of offers that are nothing, there is one that becomes your everything. A project is not given to you; rather, it is you who gives yourself to it. With both hands, you accept the file and say, “This is me.” And because Jim’s briefcase novel held such apparent failure, I refused to touch it, lest I be infected.

I know another author who has been writing a story without end. He began a novel six years ago with the plan that he’d be done within a month. The manuscript has now ballooned to over 280,000 words. And it is growing.

I told him of other writers I know, writers who’ve banged off a novel in weeks. And my voice had an anger I did not expect: “Are you not envious of them?”

“Yes,” he admitted.

I reclined, appeased.

“But they,” he said, “should be envious of me.”

The years passed, Laurene and I fell out of contact, and I continued to write in my plodding way. I was never happy with any manuscript I wrote; I was instead exhausted by them. And each time I sent one away with a prayer for it to be published, I felt a great burden lifted, as if the problem was now someone else’s.

It was usually at these times, in the lull between assignments, that I would hear the siren song of the briefcase. I wondered if, in my balking at the project, I was affecting an aesthetic sanctimony that has long precedence of being breached. Take, for example, the editors who posthumously worked on Hemingway’s The Garden of Eden, Nabokov’s The Original of Laura, and Tolstoy’s Hadji Murád. And then, too, there is Poodle Springs.

Before he died in 1959, famed detective fiction writer Raymond Chandler wrote the opening four chapters of a story tentatively titled Poodle Springs, the eighth Philip Marlowe novel. At this stage in Chandler’s career, his talent was waning, a decline epitomized by the seventh Philip Marlowe novel, Playback, which the New York Times called “his worst book.” Three decades later, after Chandler’s literary estate asked writer Robert B. Parker to complete the manuscript, the novel was published to critical acclaim, became a New York Times bestseller, and was adapted into a Tom Stoppard movie starring the leathered-but-not-yet-collagenically-frozen James Caan.

But it would be incorrect to say that Parker “finished” Chandler’s novel. Chandler reportedly left behind only thirty-one pages; Parker filled in everything else. Those opening four chapters by Chandler merely sketch the setting of the novel and reintroduce a couple of established characters. The plot itself is devised almost entirely by Parker. More than being a collaboration of writers across astral planes, Poodle Springs is fan fiction.

But the briefcase novel is not so simple. There is no identification of genre, no coherent narrative voice, no deep-pocketed literary estate offering guidance; there are no seven preceding novels that explain the backstories of Garner or Ganor. All that the briefcase offers is an endless number of pages written, with an endless number of pages to write.

And it was during one of those lulls between assignments that I quit writing. There was no one to take my resignation, so I simply said it out loud—“I quit”—and let the words fill the room. A cold sadness rose within me before draining away into a hollow calm. It was a feeling I had previously known only in breakups that I did not want to happen: when all the denial and delusion was spent and there was no longer the anguish of optimism.

I had not seen Laurene for seven years, since she handed me the novel. She had moved to a different city and disconnected her landline. (“I kept on meaning to check in,” she said when I finally got hold of her on the phone. “Just to see how Jim’s book is coming.”) On the eight-hour drive to her new suburban home, the briefcase sat shotgun, buckled in, quiet as a teenager who will not co-operate with the conversation.

When she answered her door, I was surprised by how excited we both were to see the other. In the ensuing years, she had met someone new. I’d had a child.

She said we could talk in the back, and she led me to a patio shaded by flowers blooming from trees. She set a pitcher of iced tea on the table, and the sunlight refracted through the crystal and across the lawn. There are times when I think that this career has given me every beautiful moment in my life.

But then: “So,” Laurene said, lighting a cigarette, “you’re writing an article on Jim’s book, but you’re not writing the book itself?”

I was hot with shame. “An article,” I mumbled, fidgeting with my recorder. “I just need some more information.”

Much like how the unfathomable expanse of our universe might be traced back to a pinpoint, the briefcase novel originated in a single cigarette. Jim started his novel in 1974 as a way to quit smoking. “He needed something to do with his hands,” Laurene explained. “He’d go to a restaurant and sit for hours.”

Quitting smoking didn’t last for long, but the book stuck around. By the time Jim was diagnosed with stage four esophageal cancer in 2013, it had been nearly forty years since he started his novel.

“Once the kids were in bed, he’d go downstairs, have a toke, and work on it,” Laurene told me. “He wasn’t the type to need the house dead quiet. I once had a girlfriend who was living with an author, and it was ridiculous. I said, ‘Why are you putting up with him?’”

I‘ve often thought that the worst part about being a writer is that virtually everybody can do it. The widespread practice of the craft places it only one rung above improv at the very bottom of art’s hierarchy (with, obviously, classical cello and daredevil juggling at the top).

But the more I have read the briefcase novel, the more it seems the greatest quality of writing is its ubiquity. There is the cliché that every Starbucks barista has witnessed: “Everyone has a novel inside them.” But in that sentence’s simplicity, a key fact is overlooked: it’s not that everyone can have a novel in them but that they already do, whether they want it or not—a story of great insight and revelation, a story that is full of heartache and transformation, of struggle and triumph and (if the plot requires, as Jim’s novel does) flying horses, a story that takes in the shaggy humongousness of the world and compresses it into unity, into recurring combinations of twenty-six symbols. And so, to abandon that story—how it turns chaos legible—would be to abandon all semblance of meaning and succumb to nihilism.

There is a type of novel that seems conceived to kill its writer. There’s Kafka’s The Castle, Woolf’s Between the Acts, Foster Wallace’s The Pale King. In 1969, John Kennedy Toole took his own life, leaving behind a manuscript that he had tried for years to get published. For the next eleven years, his mother, Thelma, relentlessly submitted it to publishers until one acquiesced, and A Confederacy of Dunces ascended into the canon. (There is a path to the assuagement of the dead, but how few have the doggedness to trudge it.)

All of these novels vary stylistically and thematically, but they are united in their intent: to write something—long or short—that conveys what it is like, truly, to exist. Each narrative argues that we experience life not with the enlightened rationale of the Dewey Decimal system but rather within the dark confusion of an earthquake that has toppled the stacks upon us.

The most pertinent example of a novel with Icarian aim would be Austrian writer Robert Musil’s near-2,000-page tome, The Man without Qualities, often considered one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century. Needless to say, I have not read it; but like in my English undergrad days of yore, I’ve read a handful of excerpts and now feel myself apprised. Musil began writing his book in 1921 and was still writing it twenty-one years later when he died of a stroke (not of the genius variety, mind you).

The Man without Qualities is set in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but the plot is as sprawling and labyrinthine as a slum and similarly sardined with characters. The first chapter is called “From which, remarkably enough, nothing develops.” There is no structure, no scope, no cohesion. Musil reportedly referred to his novel as “a bridge into space,” which is to say a long linking into nothingness.

Jonathan Lethem, in his introduction to the Picador Classic edition, writes, “Musil, in his torrential evocations, seems to be conducting an inventory of what it is to be alive and human.” The Man without Qualities was never finished, but not because Musil failed—rather because he struck the bull’s eye. The more accurately Musil portrayed his subjects—their stunted relationships and corkscrewing conversations, the mixed metaphors and dead-end plots—the more his novel mushroomed like a cloud. Lethem writes by the novel’s final pages, “The unpublished fragments tail into contradiction, pensiveness, and, finally, inchoate notes.” Because to build a bridge into space means that the massiveness of the endeavour will eventually outweigh its planetary anchor, and the whole globe topples off its orbit.

There is a novel that I, too, yearn to write. I have notes, I have pages, I have a hand-drawn map. I have a timeline that’s more cerebral than linear. Like Jim’s, my novel is also intergalactic; it, too, spans lifetimes, features rural Alberta, and depicts a tangible God. Once a year, I try to write it. But each time, failure is abrupt as a guillotine. Within the first sentence (“I was born on the ship, but I will not die on the ship”), I am overcome by everything moving away from me. It is a feeling so intimate and embarrassing you forget it’s universal: the harder you try to write about a subject, the more that subject eludes you. The faster you run, the faster it flees.

Every act of writing is an act of faith: that your words will hold together and take root, that they will endure the spans of doubt and insult, and that, given enough time, all of those words will blossom into something splendid and godly and you will be alive to see it. But when I sit to write my novel, all I see is a pursuit into oblivion, a bridge into space.

How to have faith in the shadow of such uncertainty, where one afternoon, after you’ve had a bit of difficulty swallowing, the specialist speaks the words “stage four,” and life is a loan called back? Laurene told me that during Jim’s sixteen months of chemo, they never discussed his novel. But there must have been moments of quiet, of waiting for the doctor, of the hypnotic beeps of medical machines. And in those moments, did Jim wish that he had worked on the novel more or not at all?

Laurene turned her face to the setting sun and I asked her for a cigarette.

She passed me one, and I said, “Do you think he knew how his book ended?”

“He didn’t chart out the story,” she replied, sparking the lighter and offering me its flame.

I thought, surely, Jim must have had some help. “In all the notebooks and notepads, there’s different types of handwriting,” I said.

I showed her pages covered in handwriting, pages written in all caps, pages written with a pen so heavy it punctures the paper.

“That’s Jim,” she said. She explained that he’d been working on the book for so long his penmanship changed.

In that moment, it appeared to me that if Jim hadn’t developed stage four cancer—even if he had lived another 100 years—his briefcase novel would never have been completed. In whatever version of the future you imagine, in whatever dimension you visit, Jim always concludes before his book does.

At some point, creation will always overtake creator. Ask Frankenstein and the scientist whose name he has subsumed. And so, as the decades drew on, is it not possible that the novel came to understand Jim better than he did? Night after night, it took his confession, gave shape to his dreams, delivered worlds made just for him. It listened to him, sat with him, watched him. And from its vantage on the desk, did it note the slight swelling of his throat as the cancer grew from stages one through four?

The novel’s characters are always saying things like: I will explain soon, but right now there’s not enough time.

O ne autumn morning, I opened an email from a woman I’d never met. She accused me of plagiarizing a short story, one that I had written a long time before and which had been recently named a finalist for a literary award. Of course, I had excuses, flimsy ones that used words like “overlap” and “pastiche.” But no one was much interested in hearing them.

Despite trying to quit writing, it never occurred to me that I could be fired. Editors disavowed me; I was suspended from teaching; in a final besmirchment, a literary magazine revoked its solicitation of an unpaid submission. I became so spiteful and indignant that I sealed myself off from the world, the way a besieged porcupine will roll itself into a ball and become pure urchin.

A couple months later, during another afternoon with nothing to do, I searched for my violin in the closet. And there it was: the briefcase. True, the novel had its issues—the glancing lecture about DNA engineering, the painstaking asides on scuba diving, a surprise cameo by Immanuel Kant—but the manuscript was so completely of itself that it would be impossible to think otherwise. Out of everything the briefcase novel was, there was one thing it was not—a fraud.

I stood in the closet’s doorway, perfectly still. Because I was no longer a writer—because I had irrefutably failed—I pulled out the briefcase and opened its lid. Here is the best I can explain the feeling: on a bus in summer, sweltering heat, the gridlock of rush hour, when someone from the back cracks open the emergency hatch in the ceiling and the ocean breeze tumbles down, and you did not realize, this entire time, you had been holding your breath.

Why did I open the briefcase once again? Because the story inside started to seem impossible in breadth and target, and I began to think that my memory had inflated the manuscript and let it loom too large, that I was cowering before a god who was more curtain than clout. I thought that by letting the story see daylight, it would evaporate, and I would be absolved of my failures.

But the exact opposite has happened. Such a fine line between a gift and a curse, between an honour and an affliction—so fine, in fact, that perhaps there’s no line at all.

And then, after all those years, Laurene is on the phone with a voice so deep with mercy she whispers: “Would you like to give the briefcase back to me?”

At first, I am polite and say no, but later in her backyard I concede and say yes, and then a few months later, while in the lineup at the post office, I decide no.

The briefcase novel has taught me nothing about writing; it hasn’t taught me how to sculpt a sentence, how to develop character, not even how to craft a sex scene (from the notebook titled “Personalities”: “They made love, and she died.”). But the briefcase novel, and the surveyor who made it, has taught me everything about being a writer.

The briefcase still sits in my closet, its lid shut tight as the mouth of a judge. I’m often hunched over my desk, exhausted, but wanting just another five minutes. Because what can damn a life’s work—condemn it to the limbo of words unwritten—is not too little time, but too much, when we are allowed to expand into our full and total selves, boundless and infinite, and alight upon an astral plane. But if such be the rules, does it not seem more of a failure to be done than undone?