Born as a doodle on a diner placemat nearly ten years ago, Wendy, the mononymous arty party girl of Walter Scott’s cult comic book series, has since journeyed through Canada’s busiest centres and buzziest scenes in her quest to become an acclaimed visual artist. In the character’s self-titled 2014 debut, Wendy, still in her early twenties, began chasing art-world aspirations, from Montreal to a woodsy artists’ retreat and back, though her attention often drifted to the eternal hunt for a good party and the affections of a skeezy drummer named Jeff.

The next instalment, 2016’s Wendy’s Revenge, sees her navigating larger ponds: an international residency in Japan, a move to Toronto, a group exhibition in Los Angeles. Wendy was still learning how to swim among the (occasionally ferocious) personalities she encountered from her place at the edge of the scene, and the offer of another beer or key bump still served as a regular diversion from her creative aspirations.

Now, third in the saga, comes the new Wendy, Master of Art, which has the scattered-yet-sweet antihero venturing off to complete an MFA in fictional Hell, Ontario. She hopes that, back in school, she’ll finally be able to define, for herself, “what an art practice—and accomplishment—means” and step—or at least stagger—into her authentic self.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

Wendy’s grad school classes are home to a motley ensemble of gadflies, ingenues, and minor celebrities ready for a Christopher Guest flick. Some are returning characters, such as Maya De Vanegas, the Martian-like rising talent who is never far from a European airport gate and can land Chloë Sevigny for a video project. Others are new faces, like Eric (permanently clenched jaw, sweaty, frets about problematic politics) and Yunji (professionally interested in “the semiotics of pissing” and “really long string”). Their professor, Cliff Masterson, is a worn-out formalist who had his last solo exhibition in 1998. Nowadays, he’s more concerned with beating traffic than with the artistic development of his students.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

Add to these ingredients Wendy, who arrives late and hungover on her first day of class and introduces herself in her typical haphazard manner: “I’m here cuz my art practice is all over the place. And I want to figure out what’s important to me.” As Wendy’s classes progress, Scott finds plenty to laugh and cry about in academia (he himself is a graduate of a similar program at the University of Guelph). The people are indeed wacky, but so is the world they inhabit.

Though Wendy’s escapades are fiction, Scott’s economical and expressionistic black-and-white cartoons may be one of the most faithful representations of a young artist attempting to climb the Canadian art world, with its hobnobbery, esoteric granting systems, imperative side hustles, and—most Canadian of all—the dream of success abroad. Wendy is a bit of a mess, but that’s at least partly because the art world she’s trying to crack into is pretty messed up too.

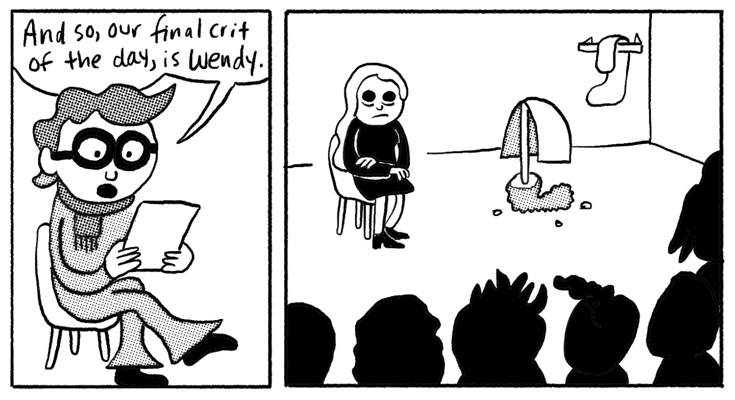

Anyone who’s attended an exhibition opening will recognize the ethnographic detail of Scott’s world: the severe hairdos, kooky eyewear, and voguish footgear are all on point; the art speak is appropriately inscrutable (from classmate Eric: “My work seeks to propagate systemic qualities of erasure in non-human logic. In speculative environments, however . . . ”). Even the stilted conversation typical of gallery chatter is polished to perfection, with the canned exit line to escape flagging chitchat—“I’m gonna check out the show”—repeated in montage. These surface pretensions are easy to skewer, though Scott executes his with uncanny precision. But it’s his keen observation of the subtler codes and behaviours domestic to the subculture that gives the Wendy series real depth. Present are the scene two-faces, the backbiters and social climbers, who are quick to bad-mouth a young artist with conjecture about “independent wealth.” Then there’s the special kind of existential crisis that can crop up after a rough class crit.

If Wendy’s story feels so true to life, that may be because it is semi-autobiographical. Scott, her Kahnawá:ke-raised, Toronto-based creator, has found more success than Wendy has—his sculptures, drawings, films, and other works have been featured in solo exhibitions at Saskatoon’s Remai Modern and New York’s International Studio & Curatorial Program, among others—but his character’s follies and frustrations, he says, have been inspired by both his own experiences and other episodes he’s either witnessed or heard about.

There is ample absurdity to wring from the fine-art ecosystem, where hierarchies and quid pro quos rule. Players ruthlessly engage in an unspoken competition for limited opportunities and resources—be they grants, residencies, publications, exhibitions, panel spots, teaching gigs, public commissions, or sales. And all of the above is adjudicated by gatekeepers who, like the gods of Olympus, deal fate and favour. This is why Wendy’s attendance at every opening is all but compulsory: each event is a potential job interview. It’s also why we find her often tethered to her laptop, where there’s always a grant application to complete, a proposal to type up, or a tweak to be made to her CV.

Wendy’s world, where artists are constantly scraping by and searching for an in, isn’t any different from our own. Few make a decent living as a visual artist: according to research firm Hill Strategies, the median income is $20,000—less than half the median income for all workers. (For artists who are women, that figure drops to $17,500. For racialized artists: $17,400. For Indigenous artists: $13,500.) Second and even third jobs are often a requisite, pushing art-making into the few moments available. In Scott’s novels, we see Wendy clocking hours behind a café counter to pay rent, taking an extra-long break from her shift to interview (unsuccessfully) for a better gig at an ad agency. Wendy’s friend and collaborator, Winona, moves back in with her mom to save money while conducting “image research.” This dismal reality fuels the fantasy of greener pastures in LA, New York, and Berlin—all of which Wendy has visited in search of the next ladder rung—where the commercial markets are larger and opportunities are perceived to be more fruitful.

Meanwhile, wealth and possibility remain tantalizingly close, with rich executives, donors, and collectors orbiting the same openings, talks, and galas as the resource-strapped artists. Across the first two Wendy books, artists, writers, and curators alike chase their favour by clamouring for the attention of VVURST magazine. (Its publishers are later exposed as wire-pullers with shady business dealings involving oil money and real estate developers.)

This is an environment, Scott says, where an artist feels like they must always show up and always be selling themselves. “I’ve definitely been invited to a biennale because I went to the right party and I was standing in the right place,” he says. Wendy’s ubiquitous partying, then, isn’t so surprising. Perhaps it’s at least in part due to the blurriness between business and pleasure. Or maybe it is a means—not necessarily the healthiest—of coping with the chronic instability. Scott’s comics offer no solution to overcome this precarity—it is, after all, difficult to rewrite the rulebook when you’re stuck to the playing board. There is an expression Wendy wears often, though, her eyes and mouth emptied into abysses, that feels especially relevant here. It appears in moments of fear, lust, boredom, exasperation, and especially powerlessness. It is the look, Scott says, of existential dread.

So, if the art game is so difficult, why does anyone play at all? Scott’s own answer is straightforward: “I like to make things.” That conviction is the beating heart of Wendy too. Though the most memorable images of Wendy may be post-party with her head in a toilet, she can also often be found alone, labouring by the glow of her laptop or entangled with works-in-progress on the floor of her studio. These quieter scenes may not be as flashy as the drinking and the drugs, but they are what art production really looks like. And, despite the heaps of bullshit Wendy must navigate—the gatekeepers, the pressures, the saboteurs and slanderers and swindlers—her commitment to her work persists because she, too, likes to make things.

It is one of the series’ longest-running gags that readers never actually get a good look at Wendy’s art. Whenever she tries to describe what she does, she’s interrupted. At her thesis defence, where she receives praise from one panel member for the “leaps and bounds” her work has grown, her pieces on display are obscured in part by Maya De Vanegas’s giant hat. “In a certain way,” Scott says, “the art doesn’t even matter.” Maybe it’s a joke about her privilege, he suggests. White, young, attractive, and well educated, “she’s the right kind of person to move through the art world.” Or maybe, he continues, “it doesn’t matter what the art is because all that matters is that she wants to make it.”

What began as a series about a young woman trying to achieve fame and fortune has gradually transformed into the story of a journeyperson. Wendy may not be an undiscovered genius, as the trope usually goes, but after three books, she’s finally on her way to becoming a working artist. This shift snaps into focus toward the end of Master of Art, when Wendy runs into an undergrad student she teaches. The latter introduces Wendy to her friend as a super famous artist who “shows in Toronto.” “I want a career like yours when I graduate!” the student says, her fawning a mirror of Wendy’s own words in earlier adventures. Success may not look as Wendy had imagined. It may, in fact, feel more like constant struggle. But she’s gotten this far by sticking with it—and isn’t that the hardest part? To some, it may seem foolish to play a game when you know it’s tilted, but it is difficult not to root for someone compelled to play anyway.