Dr. Goldfine: Bree, how does this reconciliation have a chance if the two of you can’t be honest about the innermost parts of your lives?

Bree: We’re, um, wasps, Dr. Goldfine. Not acknowledging the elephant in the room is what we do best.

Bree Van De Kamp is the most quietly desperate of the Desperate Housewives. As played by the exquisitely uptight Marcia Cross, Bree spent the first season silently navigating marital problems with husband Rex. She has since survived Rex’s sudden death—after which her only public sign of grief was a series of stunning black outfits—and accepted a dubious marriage proposal because she felt it would have been rude to decline. (“Obviously there is a downside to having good manners,” as she later explains to Dr. Goldfine.) The buttoned-up Bree may not be as conventionally sexy as her barely dressed neighbour Gabrielle, but she exudes a certain steely eroticism. Check out any fan forum and you’ll find fired-up admirers waiting for that preternaturally neat red hair to be mussed.

Meanwhile, over at the Las Vegas crime lab, Gil Grissom is hot. Despite being middle-aged and a bit pudgy, despite geeky hobbies such as entomology, despite a set of emotional inhibitions that would bring an ox to its knees, the head of the csi graveyard shift (as played by William Petersen) is way, way hot. At csi-forensics.com, one of the many websites that encourage fans to post their fictional expansions of the show’s characters, Gil is at least as big a draw as hipster Greg, and much bigger than all-American frat-boy Nick, or tall, cool Warrick. Of particular interest to the fan-fic crowd is the unexpressed relationship between Gil and Sara Sidle, which has been confined mostly to significant glances over blood-spatter patterns and—on one memorably romantic occasion—some deeply submerged flirting while the two tracked the insect infestation of a dead pig.

So why are these characters, who at one time might have been dismissed as charmless, turning out to be this season’s sex symbols? Could prime-time TV—of all things—be helping to rebrand reticence?

The values of privacy, modesty, discretion, and restraint have taken a hit in the last forty years. This distrust of emotional reserve is partly a holdover from the 1960s, when failure to voice even stray feelings and thoughts was considered hypocritical and phony. An ideological divide hardened into rigid stereotypes about who is expected to wear their hearts on their sleeves and who is expected to tuck them tidily into breast pockets. Conservatives supposedly support a collective stiff upper lip, while liberals believe in free-to-be-you-and-me emotionalism. Men are evidently from Mars, a planet where communication consists of Gary Cooperesque “yups” and “nopes,” while women are caring and sharing Venusians. wasps are expected to stare mutely into their drinks, while the sons and daughters of the Mediterranean engage in the loud, wildly gestural fights so beloved by the Italian neo-realists. All rich people are stuffy and stiff, while all poor people are given to exuberant, spontaneous outbursts of dancing, like the steerage passengers on James Cameron’s Titanic. Young people routinely embark on romantic affairs by saying, “Let’s promise to always tell each other everything,” while their more cautious elders have retreated to the fallback “don’t ask, don’t tell” position.

These either/or categories put progressive repressives like me in a bind. If we admit that over-emotionalism leaves us feeling faint and exhausted, we risk being aligned with a whole set of values that we might not actually embrace (if we were given to embracing at all, which, generally speaking, we are not). Fortunately, recent blips on the pop-culture radar seem to be offering a way to rehabilitate reserve without coming off as completely pompous. Where the control of passion was once viewed as hopelessly square, it can now be seen as sexy, smart, and self-aware. Done right, emotional repression could be the new cool.

Emotional coolness has a history. The Stoics believed that while we cannot control external events, we can control our emotional responses to them through the exercise of reason. (Stoicism saw a brief millennial revival with the release of Tom Wolfe’s A Man in Full, in which the writings of Epictetus inspire a stoic televangelistic crusade, and Gladiator, in which the aging Marcus Aurelius praises the virtues of forbearance and fortitude while a stripped-to-the-waist Russell Crowe acts on them. In the end, though, contemporary North American culture had a hard time sustaining a philosophy that declares that “wealth is the greatest of human sorrows.”) In his discourses on the virtues of the Renaissance courtier, Baldassare Castiglione advocated modesty, gentleness, grace, good sense, and discretion (along with the abilities to run, jump, swim, ride, throw darts, cast stones, vault, wrestle, play tennis, speak the classical languages, and compose poetry). In keeping with his belief that extreme positions contain their opposites, Castiglione argued for both emotion and reason, which he felt could be reconciled through the virtue of temperance.

Later, the Victorians became the image of emotional propriety; their very name is now synonymous with prudery and primness, though the layered realities of Victorian life actually illustrate how complex the balance between emotion and expression can be. While middle-class Victorians believed that some feelings should not enter into polite conversation, they could also—in modern terms—turn into sentimental mush balls, weeping publicly over the death of Dickens’ Little Nell or writing letters replete with flowery declarations of friendship. Queen Victoria herself took her protracted private mourning for Prince Albert to almost necrophiliac extremes.

Over the centuries, artists and thinkers have characterized this tension in various ways: reason vs. passion, mind vs. body, super-ego vs. id. The current skirmish involves neuroscientists who are searching for the hard-wired emotions that enable the human species to survive vs. those postmodernists who view emotions as social constructions. Apparently, in whatever way the human heart has been mapped out, the control of feeling has never been as neat or complete as the Stoics would have wished.

Emotional expression, meanwhile, has not always been as tiresome as it has become in our full-disclosure culture. When the Romantics proclaimed that “Feeling is all!” it meant something, and their exploration of the individual psyche and its most powerful emotions—sorrow, awe, ecstasy, longing—was fired by great-souled ambition. This revolutionary fervour seems to have dwindled. Rather than expanding the self to meet the world, latter-day romantics have been shrinking the world to fit the self. Leftover Romanticism has been topped up with misreadings of Freud, who has been brought in to champion emotional anarchy in ways the good bourgeois Viennese gentleman could never have anticipated. André Breton and the Surrealists hoped that Freud’s theory of dreams and the unconscious would waken humankind to complete social, sexual, and emotional liberation, something Freud found vaguely embarrassing. He himself was content with the rather more modest project of converting “neurotic misery into ordinary unhappiness.”

“Ordinary unhappiness” would never cut it in the American self-help movement, of course. Postwar pop psychology’s tendency to zero in on instant personal fulfillment reinforced the idea that any thwarting of emotion could be instantly converted into unhealthy neurosis or even physical disease. Amid this emotional free-for-all, our culture began to jettison the idea of decorum, the notion that displays of feeling should occasionally be circumscribed by time, place, or audience—that not everything needs to be expressed, for instance, “in front of the children,” on a cell phone in a crowded elevator, at the wedding of one’s former lover, or during a teary appearance on daytime TV. We increasingly used self-expression as a justification for all sorts of bad behaviour on the grounds that to do anything other than what our natural feeling dictates is hypocritical.

But, really, what’s wrong with a little hypocrisy, wonders Judith Martin, a.k.a. Miss Manners, North America’s best-known arbiter of etiquette. Though occasionally expected to pronounce on matters of fish-knife placement, Martin spends much more time dealing with the moral foundations of civilized society. Within this framework, she finds social hypocrisy vastly preferable to expressions of unkindness, no matter how existentially authentic they may be. As she writes in the modestly titled Miss Manners Rescues Civilization: “People seem to have an inordinate amount of interest nowadays in their own feelings. This does not strike Miss Manners as quite decent. First they put an enormous effort into examining themselves, in the hope of discovering what their feelings actually are…. Then they act on those feelings. This requires no thought at all.”

All of this puzzles Miss Manners, who always knows exactly how she feels, and considers the question of how and when to express or to act upon one’s feelings to be a highly complex subject—namely, etiquette. Martin wishes to remind her “gentle readers” of the difference between feelings, to which we are all entitled, and the notion that all feelings must be yanked, half-formed and gasping, into the open air.

We should make clear that those of us who find reticence sexy—let’s call ourselves the New Repressives—are not advocating cold-fishiness of any sort. We seek not to extinguish emotions but to focus them by using reflection, self-knowledge, and the judicious ability to occasionally shut the hell up. We’re for feeling passionately but expressing selectively, because it’s in this gap that interesting things happen.

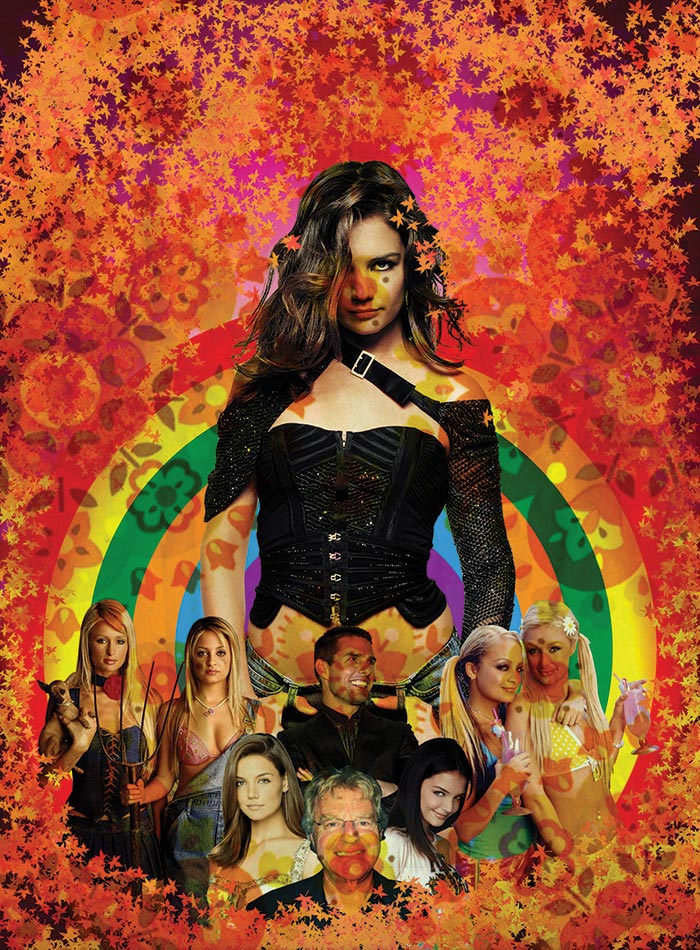

The last decade has established the tedium of hyper-emotionalism with a queasy display of over-sharing celebrities and tell-all autobiographies, chair-throwing talk shows and invasive reality TV, and the cyber-exhibitionism of blogging. We may have reached a tipping point, though, if the recent fascination with buttoned-up TV characters is any indication. It’s doubtful that this development marks a pop-culture paradigm shift. It’s probably not even a trend. Emotional subtlety and stringent self-analysis will likely remain the territory of Booker Prize winners and Joan Didion memoirs. But the mass media’s puppy-like attention span has seized on the prickly pleasures of uptightness—at least for a moment.

Consider the contrasting celebrity trajectories of Tom Cruise and Madonna. Though he’s known for his portrayals of callow, cocky operators, Cruise once maintained a sense of mysterious depth through the ruthless gatekeeping of his public image. And then suddenly there he was, getting all schmoopy with Katie Holmes and scaring Oprah by going down on his knees, pounding the floor, leaping on the furniture, and screaming his love on national television. (According to urbandictionary.com, the phrase “jumping the couch” is now used to describe “a defining moment when you know someone has gone off the deep end.”) Meanwhile, we have Madonna, the “Express Yourself” girl once known for nude hitchhiking. With her cool eye for zeitgeist zigzags, she sensed that total exposure had temporarily exhausted itself and embarked on a calculated dalliance with British propriety and reserve. In last August’s Vogue the reinvented Madge was pictured on the English estate she shares with husband Guy Ritchie, feeding the chickens in a ladylike dress and cardie.

Public reaction to these PR reversals suggests a new mood. Cruise nearly scuttled the War of the Worlds publicity push when his fans discovered that, um, actually, they didn’t want to see “the real Tom” and his icky, inappropriate public displays of affection after all. The newly demure Mrs. R., on the other hand, piqued our interest—even if it was only to marvel at her unabashed media manipulation.

Madonna’s passing passion for primness—she’s already reworked herself as a disco diva—may have been a shrewd show of self-marketing. And csi producer Jerry Bruckheimer, known for loud, bombastic movies such as Armageddon and Pearl Harbor, is probably backing his uncommunicative investigators for strategic reasons. As shrewd pop-culture prognosticators, they have both seized on emotional repression as a novelty, a cool contrast to the emotionally overheated effects of most mass media, including the web.

Cyber-theorist Rebecca Blood’s early optimism that the blogosphere could be a community dedicated to self-awareness, self-reliance, and critical thinking was a wonderful leap of Rousseauian idealism, and the blogs that live up to that standard are models of democratic social engagement, with writing fresh enough to merit Blood’s definition of blogging as “a coffeehouse conversation in text.” Unfortunately, most of blogworld material doesn’t warrant this kind of optimism. Instead, it offers sullen and adolescent evidence that personal expression does not necessarily lead to a greater understanding of the self and others. Blood believes that “each of us [bloggers] speaks in an individual voice of an individual vision,” but just try googling the phrase “I hate my mom” or “Nobody understands me” or “My love life sucks” and see how many hits you get—and how drearily alike the entries are. Many bloggers seem to be caught in circular thinking and world-obliterating self-absorption. They can’t be doing anything for their audience, and it’s not even clear what they’re doing for themselves.

It’s hardly surprising that it is British researchers who have discovered that venting may not necessarily be good for you. According to a 2004 study of 153 Staffordshire University students, people who write in journals—the online diary’s low-tech cousin—are more likely to suffer from insomnia, headaches, social dysfunction, anxiety, indigestion, and generally feeling crappy. The most morose are those who go back and reread old entries. Psychologist Elaine Duncan of Glasgow Caledonian University speculates that rather than providing a cathartic experience, diary-keeping traps many of its practitioners in a “ruminative, repetitive cycle.”

Emotion usually benefits from editing. Unmediated feeling has a certain raw power, but once it’s out there it has only one place to go. Its limitations remind us of George Lucas’s legendary piece of advice for the actors in the original Star Wars movie: “Faster, more intense.” Reality television is a good example of a genre that has gotten about as fast and intense as fast and intense can be, without getting any better. Turning the camera on friends and family as they indulge in psychological slapfests of resentment, envy, self-pity, petulance, spite, and self-entitlement, these shows routinely remind us that many feelings are unhelpful or just plain unseemly. The Jerry Springer Show (“I Slept With My Sister’s Fiancé,” “Wives vs. Mistresses!”) is an instant, ice-water antidote to the warm, fuzzy idea that any emotion is valid simply because one happens to feel it.

It may seem counterintuitive, but emotional expression is often one-dimensional, while sublimation has a thousand fascinating faces—irony, enigma, understatement, indirection, Cole Porter-style insouciance, and blessed quiet. One of the advantages of scripted dramas, which have recently made a hard-fought comeback against reality TV, is that characters can finally be ordered to stop talking. Prime time is now awash in meaningful silences. Along with the familiar stoics of Law & Order reruns (the sardonic Lennie Briscoe; the stiff, upright Benjamin Stone; Adam Schiff, the weariest man on television), we have the down-to-business gang at Without a Trace, led by the literally and figuratively tight-lipped Jack Malone (Anthony LaPaglia), and the oh-so-complicated Jack Bauer (Kiefer Sutherland) of 24.

The model of Gil Grissom’s remote paterfamilias leading his crime-lab family has proven so effective that the expanding csi franchise has continued to replicate this dynamic, first with Horatio Caine (David Caruso) in Miami and later with Mac Taylor (Gary Sinise) in New York. Each csi episode presents viewers with a puzzle about how some poor stiff came to die, but the larger, underlying mystery involves the living characters—their feelings, their pasts, and their tortuously tamped-down relationships. Eschewing the common TV practice of lunkheaded exposition, the writers tease out backstories gradually, often over many episodes or even years. (Sara has daddy issues; Warrick was a compulsive gambler.) Everyone gets one case a season to take personally—because of parallels with some hidden desire or past trauma—but the rest of the time the staffers are expected to behave with terse professionalism.

csi treats its characters with a certain tact, allowing them private lives that remain private, and the show’s consistently high ratings over five seasons suggest that audiences are intrigued rather than frustrated by this emotional circumspection. Tired of having every subplot handed to them, people want to make discoveries for themselves.

In his landmark 1960 work, Art and Illusion, art historian E.H. Gombrich argued for the importance of “the beholder’s share,” suggesting that ambiguity allows viewers to actively engage with a work, to indulge in the pleasure of projection, to exercise their imaginations, and—on a slightly less elevated plane—to be flattered by the feeling of being “in the know.” csi’s fervent fan-fiction following is a cyber-age confirmation of Gombrich’s ideas. These viewers are driven to fill the show’s suggestive gaps with their own stories, and it’s no coincidence they like the emotionally cagey characters the best. (Fan-fiction has a significant history with emotional repression: in the 1930s, a group calling itself the Baker Street Irregulars began writing stories about that desiccated calculating machine, Sherlock Holmes. Spockanalia, an early fanzine first published in 1967, was devoted to Star Trek’s resident rationalist, Mr. Spock.)

The ambiguity of Desperate Housewives lies in its odd tone. Is it wacky comedy or dark mystery, a satirical take on middle-class hypocrisy or an affectionate homage to the women who hold suburban life together? Desperate Housewives exposes Wisteria Lane’s dark secrets (the murderer in the minivan, the country-club prostitute, the noises in the basement), but it also celebrates such retro notions as “the polite fiction” and “the social obligation.” TV audiences seem to be fascinated by the mix of hidden sin and surface decorum—a tone that soap operas invented of course—and this uneven show works best when it’s almost impossible to tease them apart. Take a scene in which Bree politely plays out her hostile relationship with son Andrew by blackmailing him into attending a dinner party. He’s stunned, but she acts as if she’s merely being punctilious. “You don’t know the lengths I’d go to for even seating,” Bree tells him, and, you know, we really don’t know.

Freud believed that the requirements of civilization hunker down on our instincts “like a garrison in a conquered town.” If it’s true that we’re condemned to this internal division, then the gap between emotion and expression is more than just a way to heat up TV ratings: it’s a place where we can learn something essential about what it means to be human. Within this view, emotion and expression aren’t in stark opposition; they’re in a tricky, tantalizing, revealing relationship. Words left unspoken, feelings kept constrained take on a different kind of eloquence. If we have to live with the forces of repression and denial, then why not find a way to explore, even enjoy them?

“You’d settle for that? ” Dr. Goldfine asks Bree. “A life filled with repression and denial? ”

“And dinner parties,” she replies. “Don’t forget the dinner parties.”