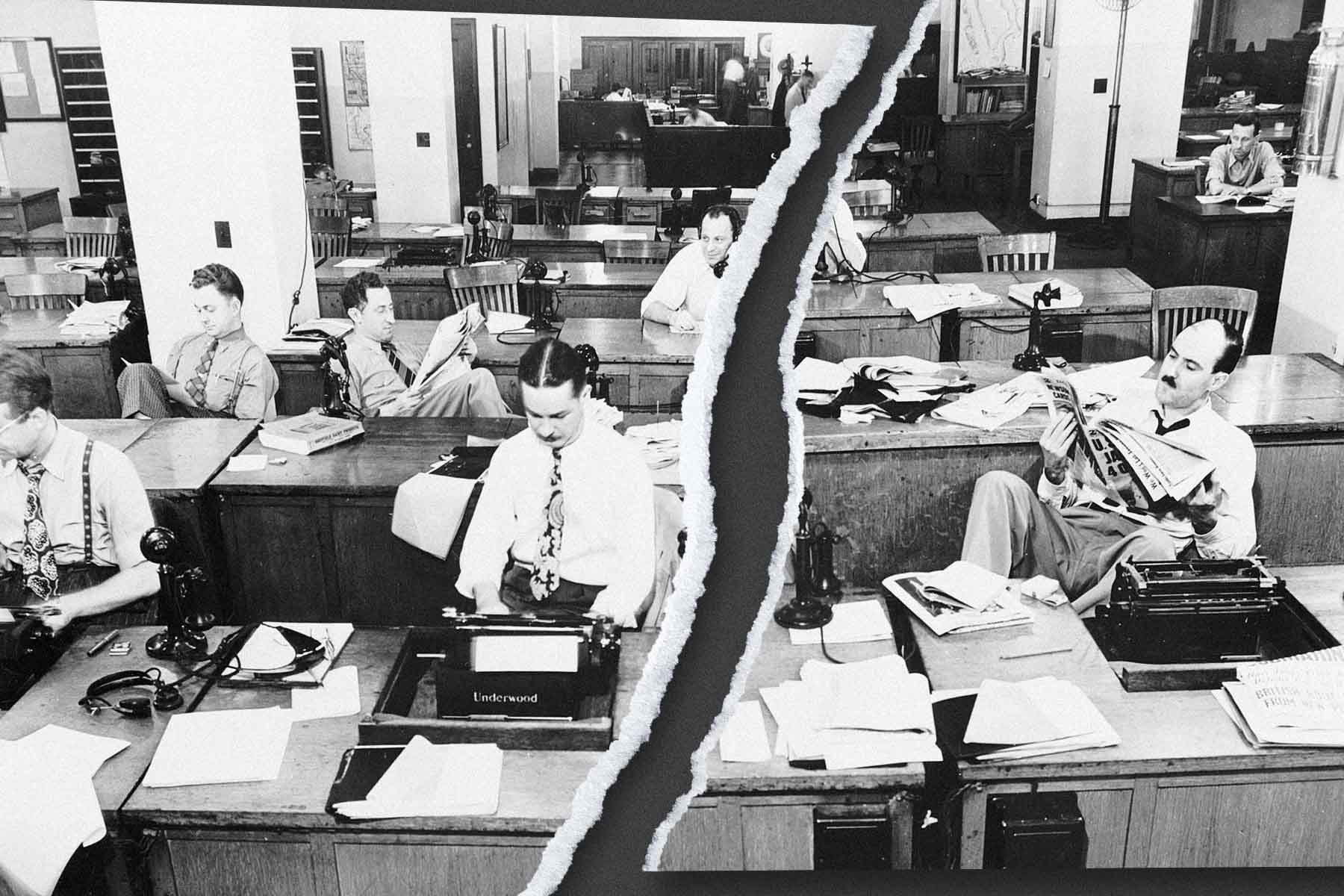

Early in the film All the President’s Men, rookie Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward, played by Robert Redford, hunches over his typewriter, hurriedly filing the first story on what will become the Watergate scandal, the clacking of his typewriter harmonizing with the cacophony of ringing phones and hushed, urgent conversations all around him. Moments later, he catches his fellow reporter Carl Bernstein, played by Dustin Hoffman, rewriting the story. “I don’t think you’re saying what you mean,” says Bernstein, lecturing Woodward about his fuzzy lede. “Yours is better,” Woodward concedes, then dumps a pile of meticulous notes on Bernstein’s desk with an admonishment: “If you’re going to do it, do it right. Here are my notes. If you’re going to hype it, hype it with the facts.”

The bruising of male egos, the thrumming urgency, the obsessive commitment to getting the story right—the 1976 movie symbolizes the golden age of journalism and the potent, vital energy of the newsroom. It’s scenes like this that Maureen Dowd, who got her start in journalism in Washington during the Watergate years, evokes with tender nostalgia in a recent New York Times column. She pays tribute to the rowdy newsroom of her youth, where tantruming reporters would smash “their typewriters or computer terminals on the floor.” Those days are over, she laments, noting that, today, the only reason her Slack-reliant colleagues come to the office is the free bagels. Dowd’s colleague Jim Rutenberg wondered wryly if a contemporary movie about journalism might instead feature “individuals at their apartments, surrounded by sad houseplants, using Slack?”

It’s inarguable that newsrooms everywhere have changed. Watching Hollywoodized depictions of the Woodward and Bernstein era today makes one feel like Dian Fossey peering through the mist at a threatened group of mountain gorillas. Journalists are more likely to file breaking news from their couches, particularly as newsrooms blink out like expired light bulbs.

Stories about the dying newsroom are often bound to the larger tragedy of our declining media landscape. As Tajja Isen recently wrote, once-ascendant digital outlets like BuzzFeed News and Vice are dying off at an alarming rate. Traditional media is suffering too: in 2018, the Local News Research Project reported a loss of over 250 Canadian news outlets in the previous decade. According to the COVID-19 Media Impact Map for Canada, between March 2020 and August 2022, fifty-six news outlets permanently closed, while 183 cut staff. In the United States, according to Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications, more than 2,500 newspapers—more than a quarter of all papers—have closed since 2005, at an astonishing rate of two per week. These losses have been devastating not only for journalists but also for readers, particularly those of community newspapers, which have suffered the greatest number of casualties by far.

But the decline of the newsroom itself is not the same thing as the decline of media, and conflating the two obscures how the newsroom culture venerated by legacy journalists is precisely what needs to die so that the industry itself can survive.

A 2021 survey of 209 newsrooms by the Canadian Association of Journalists found that almost half employed only white journalists; eight in ten outlets had no Black or Indigenous journalists. Racialized staff were more likely to work in part-time or internship positions and proportionately less likely to hold leadership positions. The exclusion isn’t unique to Canada: Dowd’s employer, the New York Times, confirmed to Canada’s National Observer last year that there were zero Indigenous people among its 1,700 reporters. Journalist Bailey Martens has written about the underrepresentation of disabled people—over 20 percent of all Canadians—in journalism, her own experience of being unable to even enter the newsrooms where she worked due to issues such as an inaccessible entranceway and non-functional accessibility buttons, and being told at a journalism conference that she was too much of a liability to be hired. Female journalists, even when their numbers approach parity, report frequent instances of sexual harassment, physical threats, and racism.

In Dowd’s view, the magic of the newsroom—the collaboration, the mentorship, the camaraderie she enjoyed—is inseparable from the culture of late nights, obsessive overwork, heavy drinking, and volatile personalities. But those factors have also made newsrooms hostile places for many journalists and editors—spaces that tolerate the brashest personalities and blatant favouritism. When one of Dowd’s colleagues grieved the loss of the invaluable “little meetings after the meetings” to her, it didn’t occur to either of them to wonder who was invited to stick around for those—and why. Last year, the Globe and Mail reported that three formal reviews of Bell Media newsrooms had been initiated in recent years over incidents that included “alleged bullying by managers, sexual harassment, and the use of the N-word during an inclusive-leadership training session.” Many staff members endured the worst elements of the newsroom culture without getting to participate in its promised benefits.

There’s also a streak of generational resentment in newsroom eulogies like Dowd’s: taking digs at young reporters who text sources instead of picking up the phone, who stare at their computers instead of gossiping with fellow reporters, who might prefer the company of their pets to the din of an office. Dowd is mystified by the remote-work preferences of her younger colleagues, writing, “At that age, I would have had a hard time finding mentors or friends or boyfriends if I hadn’t been in the newsroom.” Even if you sidestep the land-mine implication that inter-office flirtation is a perk, it’s not a sign of decline that many young people want an identity separate from their work, whether they’re in journalism or any other industry. Cultivating a personal life outside the office also shields one from an existential crisis when that industry inevitably evolves or evaporates. After all, the greatest journalism—of this era and every other—wasn’t about what happened around the desk, in the boardroom, at the impromptu meeting-after-the-meeting, but on the ground, where the stories themselves have always unfolded. The most riveting scenes of All the President’s Men take place in parking garages and doorsteps.

Many laments invoke the declining cinematic quality of modern reporting. The great movies about journalism—All the President’s Men, Spotlight, The Ring—are movies about brilliant, dogged reporters whose efforts to uncover the truth eventually pay off in vindication. But they’re also set, realistically, in dreary, beige offices full of harried, rumpled employees talking on the phone. If there ever was “louche glamour,” as Dowd puts it, it was in the prestige of the work itself: the possibility that all the typing might pay off in a history-making story, one that casts the journalist as hero and saviour of democracy, freedom, and justice. But it is this purported glamour of the profession that has long served to justify the poor treatment of racialized employees, the tolerance of volatile personalities and heavy drinking, the long hours and low pay.

Today, journalists have a different reputation than in the decades past, marked by growing public distrust: a 2022 survey by Edelman found 61 percent of Canadians worry that reporters are misleading them. It’s natural to yearn for an era when journalists were respected, or at least when they didn’t have to put up with so many annoying online comments and replies—not to mention harassment for having a particular job title. But returning to the era of in-office drinking and brawling won’t get us there.

The cultural changes in journalism aren’t a sign of decline; they’re a sign of persistence despite decline—wildflowers sprouting in the cracks of a fracturing industry, signs of new life amid the decay. They’re worth nurturing as we strive to rebuild the media landscape into something new. When the clatter of the old newsrooms dies down, there might finally be a chance to hear the voices we’ve been missing all this time.

Correction, June 2, 2023: An earlier version of this article stated that a newsroom where Bailey Martens worked had stairs that made it inaccessible. In fact, it was a single step. The Walrus regrets the error.