Rosa Elbira Coc Ich says she was cooking at home when the men with guns came on January 17, 2007. The women and children of her village were busy preparing food and tending to domestic tasks, while the men farmed in the fields.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more Walrus audio, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

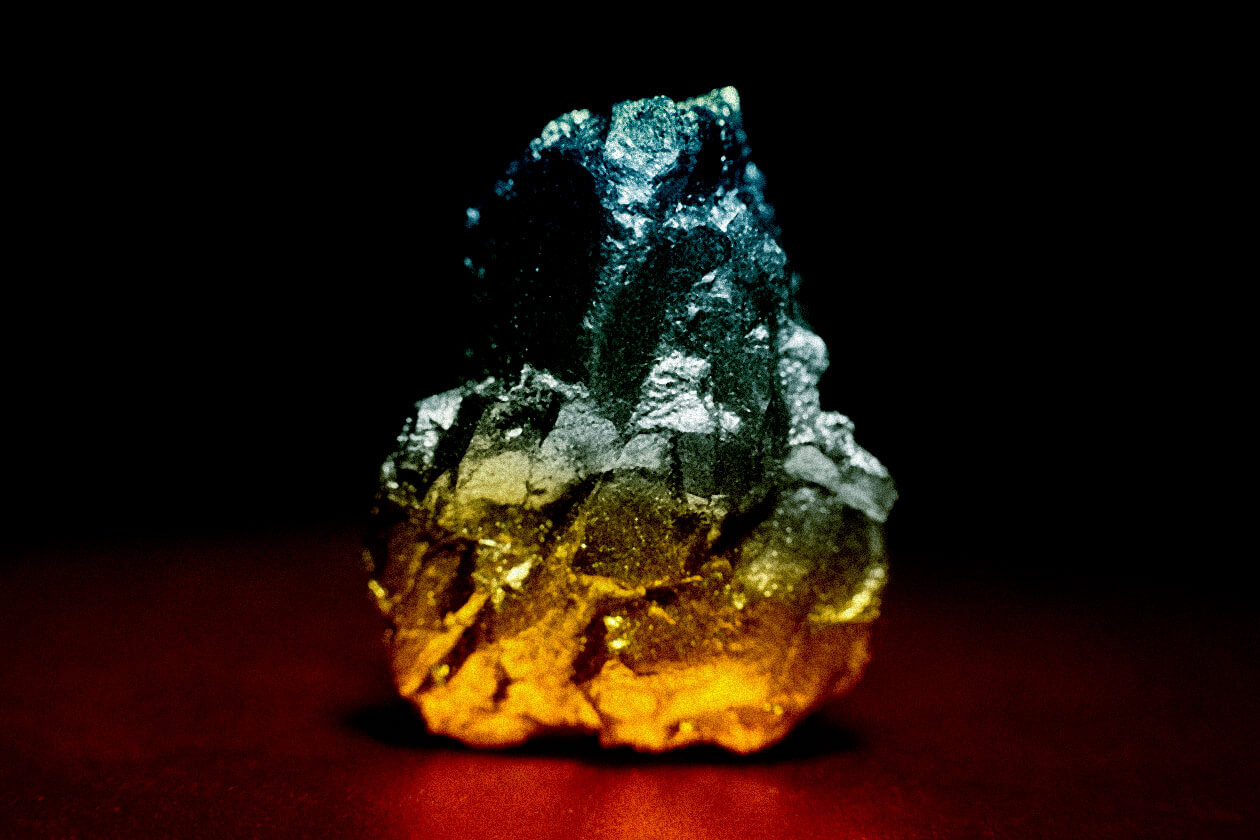

In a signed affidavit, Coc Ich describes seeing the men with guns before: about a week prior, hundreds of them swept up the remote region of eastern Guatemala, burning homes down to charred rubble while evicting at least five Maya Q’eqchi’ communities. Coc Ich’s community of Lote Ocho, a small farming village about a six-hour drive northeast of Guatemala City, had been targeted. Those lands, the communities had come to understand, purportedly belonged to the Guatemala Nickel Company (CGN), a subsidiary of Canadian mining company Skye Resources, which amalgamated with Hudbay Minerals in 2010.

Coc Ich, a Maya Q’eqchi’ woman, had spent all of her life on those ancestral lands before the police and military came to destroy the dozens of wood and thatch houses. She fled with her neighbours farther up in the mountains, to hide in the highlands. A few days after the eviction, when the armed men left, the villagers returned to rebuild. They collected plastic, nylon, string, and bamboo to repair their huts, and they tended to their fields of beans, corn, squash, and cardamom.

The armed men then paid the village a second visit. As the vehicles approached, filled with hundreds of military, police—and, according to some witnesses, private security guards—some villagers began to run while others tried to gather their belongings. Coc Ich, twenty-two at that time, says she stayed inside her home, the hut she had begun to rebuild.

Coc Ich describes how the men barged in, and a police officer pointed a gun at her head, asked where her husband was, and threatened to kill her. Coch Ich replied that she didn’t know. The men began smashing things, including her bowls and cooking utensils. Then she was thrown to the ground, and her clothes, a traditional Maya blouse and skirt, were ripped off. She was held down; her mouth was covered. But she says she could see, affixed to some of their uniforms, chest patches that read “CGN” (though Hudbay argues that there were no CGN personnel or private security contractors at the scene that day); others were military men, dressed in fatigues, and national police officers, in black uniforms. “I thought only one of them would rape me, but instead all nine men raped me, one after the other, on the floor of my home,” she says in the affidavit.

Coc Ich is one of eleven women in the community of Lote Ocho who say they were gang raped that day, in similar circumstances, and are suing Hudbay Minerals. Two of the women were pregnant—one suffered a miscarriage, the other gave birth to a stillborn baby. Others, including Coc Ich, cannot have children. “I think that I am not able to have children because of the violent way that they raped me,” Coc Ich says in her affidavit.

Coc Ich lives in the northeast of the country near the Fenix mine, but her story is not exceptional. Deodora Hernández, a woman who lives in the remote western highlands, near a Canadian gold mine in San Miguel Ixtahuacán, was shot in the head. And seven men from the southwest, near a Canadian silver mine, also claim to have been injured when security personnel shot at them. All are victims of the Canadian government’s failure to regulate and standardize corporate behaviour abroad.

The year 1996 marked the end of three-and-a-half decades of civil war in Guatemala and the beginning of a more aggressive neoliberal development agenda, partly through licenses with Canadian extractive companies. A year later, Guatemala amended its national mining law to encourage foreign investment, a decision that would fuel conflict between companies and communities for decades to come.

According to geographers Catherine Nolin and Jacqui Stephens, who studied the work of Canadian mining companies in Guatemala from 2004 to 2008, Canada’s “pro-business, pro-mining stance, through its embassy’s activities,” have shaped Guatemala’s development model and, in turn, have helped plunder the resources of Indigenous and local communities. Documents received through Access to Information requests show that the embassy was active in creating a favourable environment for the operation of Canadian companies. This included forming ties with Otto Pérez Molina, Guatemala’s president from January 2012 to September 2015 who was imprisoned in 2015 for his alleged involvement in a multi-million dollar customs corruption scandal. Pérez Molina is an ex-military and intelligence officer, trained at the US Army School of the Americas. (The school trained several of Latin America’s dictators over the past fifty years, and it has since closed—though a very similar institution is now open in the same location.) According to the National Security Archive, Pérez Molina was allegedly involved in “scorched earth campaigns,” which annihilated entire Indigenous villages during the country’s civil war.

In 2011, a couple of weeks after Pérez Molina was elected president, an embassy attaché sent an email to then–Canadian ambassador Hughes Rousseau about a meeting with the future Guatemalan mining minister, which included: “The recently elected government and the current conjuncture is being seen by the mining sector as a good momentum to move forward on the discussions about the mining law and its implications. Apparently the extractive sector . . . is showing genuine interest to initiate dialogue with the government.” To which Rousseau responded, “I spoke with OPM [Otto Pérez Molina] tonight about a request [REDACTED]. I also told him we were eating with his chosen mining minister. Very happy with our approach.”

About a year later, in February 2012, the vice president of corporate affairs of Canadian mining giant Goldcorp—one of the first Canadian companies to operate a mine in Guatemala’s postwar period—went before a Canadian parliamentary committee meeting and described what appeared to be the expectation of a close level of co-operation between the Canadian and the Guatemalan governments:

“In Guatemala, I would like to see them modernize their mining regulations. That would add to the stability of the environment within which we deal in Guatemala. Can I go as Goldcorp and start training the Ministry of Energy and Mines? I can’t do that. The credibility behind that is not right. However, I think it makes a lot of sense to have a government institution come in to take our experience here in Canada—Natural Resources Canada in terms of their experience—and bring that experience to Guatemala.”

Documents shared by Shin Imai, a law professor at York University and director of the Justice and Corporate Accountability Project, suggest that the embassy played a key role in these industry gatherings. At one point, over the issue of land confrontations between Maya communities and Canadian companies, the embassy, in its internal communications, even referred to the Indigenous people as “invaders.”

At least four security groups hired at Canadian-owned mining sites in Guatemala have been accused of having questionable human rights records. Some of their members are said to have trained in counterterrorism, to be operating without weapons licenses or registration with the state, or to have ties to the Guatemalan military during the country’s civil war. The UN-backed Commission for Historical Clarification, set up after the war to investigate human rights violations, found that state forces and related paramilitary groups committed 93 percent of documented violations during the civil war; now, some of these same forces are working privately in the mining industry.

Mynor Padilla González, for example, is a former lieutenant-colonel in the Guatemalan army who later headed security for CGN—the security company whose personnel were allegedly involved in the gang rapes of Coc Ich and other women in Lote Ocho. He stood trial in Guatemala—and was found to be not guilty earlier this year—for the murder of Adolfo Ich Chamán, an Indigenous community leader and teacher who was allegedly hacked with a machete and shot in 2009 by CGN’s security personnel. The Attorney General’s office plans to appeal. One of Ich Chamán’s five children, José, witnessed the incident and described it in a sworn court document:

“Approximately 10 or 15 security personnel surrounded my father, and continued to lead him away . . . My father began to resist. He didn’t want to go with the security personnel, so they started to hit him with their guns. My father raised his arm to defend himself, and one of the security personnel struck my father in the arm with a machete. The machete blow almost cut my father’s right arm off. Mr. Padilla then shot my father in the head, and he fell to the ground . . . I could see that he was dead.”

The day Ich Chamán was killed, protests erupted related to land disputes with Hudbay, which had amalgamated with Skye Resources in 2008. Padilla González allegedly led a group of men with bulletproof vests, machetes, guns, and tear gas to curb the protests. Padilla González was charged for—and acquitted of—shooting a man named German Chub Choc, who had been watching a soccer game and was allegedly shot without provocation; the man survived, but he is now paralyzed and has lost the use of his left lung.

Although Guatemala is now on the other side of a fractious civil war, it remains a country in which seeking access to justice comes at a cost. According to a 2013 report by Human Rights Watch, “98 percent of crimes in Guatemala do not result in prosecutions.” In a 2017 report, Human Rights Watch concluded, “corruption within the justice system, combined with intimidation against judges and prosecutors, contributes to high levels of impunity.”

Canadian mining companies around the globe, some listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange, have also escaped any kind of reckoning. They have been at the centre of controversies involving allegations of environmental damage, slavery, child labour, mass sexual assault, and murder—and have even been accused of indirectly financing terrorism.

According to a report by the Washington-based think tank Council on Hemispheric Affairs, “The Canadian government actively assists the extractive industry without requiring that their mining companies respect the environment and human rights.”

To date, not a single one of these companies has been held legally responsible for corporate or employee misconduct abroad, nor are there any effective mechanisms in place to investigate such complaints. That may soon change. With the help of Canadian attorneys at the Toronto-based Klippensteins law firm, German Chub Choc, Angélica Choc (the widow of Adolfo Ich Chamán), Rosa Coc Ich, and ten other women from Lote Ocho are suing Hudbay in Canada for negligence, and seeking damages.

The case is likely the first of its kind in Canadian courts. In a 2013 decision, an Ontario Superior Court Justice left open the possibility for a Canadian company to be held accountable for the human rights abuses of its subsidiaries abroad. The attorneys for the victims hailed this as an unprecedented step in Canadian corporate accountability: “Corporations be warned—this case clearly shows that Canadian companies can be sued in Canadian courts for alleged human rights atrocities committed at their foreign operations.”

Scott Brubacher, director of corporate communications for Hudbay, had a different opinion. In an email, he wrote the same text that is posted on Hudbay’s website: “The ruling did not make any determinations with respect to the facts of the cases, does not set any legal precedent and simply said that, if the facts as pleaded by the plaintiffs are true (which Hudbay vigorously disputes), it is not plain and obvious that the cases would fail.”

As the plaintiffs await their day in court, their situation remains difficult. The women of Lote Ocho claimed they have been threatened, intimidated, and called “prostitutes.” On a Friday evening last September, just after midnight, Angélica Choc, the widow of Ich Chamán, was sleeping at home in El Estor with two of her children when two unidentified assailants fired shots at the cinderblock wall of her home. “We interpreted that as a clear threat and warning to her, and we think it’s motivated entirely by this lawsuit,” said Cory Wanless, co-counsel for the plaintiffs.

The town of El Estor is surrounded by mountains and sits on the northern shore of Guatemala’s largest lake, Lago de Izabal, a 320-kilometre drive from the capital. Along the main road, it takes Rosa Coc Ich more than two hours to walk from El Estor up the mountain to Lote Ocho. Like those in Lote Ocho, the Maya Q’eqchi’ who inhabit the municipality of El Estor have been in conflict with Canadian mining companies for years over contested land. The Indigenous people had already been evicted from their ancestral territory during the civil war, by the dictatorial military government, in part to make way for mining. But in 2011, according to several statements of claim against Hudbay, Guatemala’s highest court ruled that Maya Q’eqchi’ communities have valid legal rights to those contested lands.

Near El Estor, the land around the Fenix nickel mine has been passed from one Canadian company to another since the 1960s. The original land concessions, which included the Lote Ocho territory where Coc Ich lives, were granted by the military regime following a US-backed coup in 1954. Six years after the coup, the Canadian International Nickel Company (INCO) began negotiations to build an open-pit nickel mine, the same year the civil war erupted between the Guatemalan government and leftist groups. INCO was granted a mining lease in 1965 through its subsidiary, EXMIBAL.

A movement soon emerged to block the contract. A 1999 report on state violence by the International Center for Human Rights Investigations and the American Association for the Advancement of Science says that the contract was seen by intellectuals and political opponents as a business deal meant to fill the pockets of the political and military elite. The report found that, in the early ’70s, Guatemala’s former president, Colonel Carlos Manuel Arana Osorio, suspended constitutional guarantees and used mass detention and death-squad executions to quell opposition—some of which purportedly involved EXMIBAL employees. Arana Osorio was already known colloquially as “the butcher of Zacapa” for his earlier brutal counterinsurgency campaign.

On May 29, 1978, approximately 700 Indigenous Q’eqchi’ people from neighbouring villages gathered in the town square of Panzós, a village not far from Lote Ocho. They were protesting the land sales to INCO and their ousting from the land their families had lived on for around a century. According to a 1998 Amnesty International report, soldiers encircled the town square and opened fire on them. It is estimated that more than 100 people were killed, and some may have drowned as they attempted to flee. The casualties, however, are difficult to count: the army sealed off the town, and the dead bodies were dumped into a mass grave. According to Amnesty International, some observers said that the killings were connected to the fact that nickel and oil had recently been discovered in the area.

The massacre incited some of the survivors and their descendants, including those of Coc Ich’s generation, to become involved in land disputes with INCO’s successors, Skye Resources and Hudbay, decades later. “On any given day you can go into the community of Lote Ocho and say, ‘How many of you have family members who were killed in Panzós?’ and a significant number of people will raise their hands,” says Grahame Russell, a Canadian activist and attorney.

INCO’s operations were halted in the 1980s, in the midst of the country’s three decades of fratricidal war. Between 1962 and 1996 the Commission on Historical Clarification estimates that more than 200,000 people, mainly Indigenous, were murdered or disappeared, and many more were displaced in Guatemala’s counterinsurgency operations and scorched earth campaigns. The Commission found that it was Maya women who bore the full brunt of institutionalized violence. “Rape of women, during torture or before being murdered, was a common practice aimed at destroying one of the most intimate and vulnerable aspects of the individual’s dignity.”

The war ended in 1996 with the signing of the Peace Accords, but for the people in Lote Ocho, some of the same land disputes and violent conflicts continued, with many of the same political and military figures still active in the country—including Padilla González and Pérez Molina.

The collaboration between large multinational extractive companies and former military officials is common in Guatemala. According to Otto Argueta’s 2013 book on the proliferation of private security in Guatemala, private security guards outnumber police by approximately five to one. Coc Ich’s legal complaint against Hudbay for negligence and for the sexual violence she and other women suffered asserts that the company “knew or should have known, that individuals who were former members of the Guatemalan military and paramilitary groups during the Guatemalan Civil War were employed as part of Skye’s Fenix Security Personnel.”

As confirmed by military documents, Mynor Padilla González, the head of CGN’s security, was in the Guatemalan army from 1981 until 2004. CGN also contracted with a company called Integracion Total, whose personnel allegedly carried weapons without licenses and registration, and were hired without background checks, according to the Ontario civil claims case (which Hudbay disputes).

Scott Brubacher, the director of corporate communications at Hudbay, says that publicly available documents report that nobody was present in the village the day of the evictions, meaning the alleged sexual assaults never occurred—and did not involve CGN security personnel. What’s more, “Hudbay did not have any ownership position in CGN at the time these alleged events are said to have occurred. Hudbay is a party to the litigation only as a result of an acquisition,” he wrote in an email.

After Skye Resources purchased the Fenix project from INCO in 2004, it amalgamated with Hudbay in 2008. According to the Ontario court’s judgment, Hudbay is legally responsible for Skye’s legal liabilities after its amalgamation.

In a response to the court cases posted on its website, Hudbay said its former subsidiary, CGN, had approved a formal human rights policy. Brubacher confirms that Hudbay had committed to the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights in 2011, which calls on companies to do a risk assessment of the environment in which they operate, to “consider the available human rights records of public security forces, paramilitaries, local and national law enforcement, as well as the reputation of private security.”

These are the same principles to which other Canadian mining companies have signed on, but they are entirely voluntary, and critics say that the Canadian government doesn’t require adequate oversight or accountability for their violation. The government prefers, instead, to allow companies to adhere to voluntary guidelines under its Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) framework.

Canadian officials in Ottawa and the embassy in Guatemala declined numerous interview requests to speak over the phone or in person about mining in Guatemala, answering questions only by email. “It is Canada’s view that voluntary CSR initiatives advance public policy objectives in a more flexible, expeditious, and less costly way than regulation or rigid legislative regimes,” Amy Mills, former spokesperson for Global Affairs Canada, explained.

Two other Canadian mining companies in Guatemala have adopted those same voluntary principles, while their private security companies have also been caught up in alleged human rights abuses.

Around 400 kilometres west of Coc Ich’s home, Deodora Hernández is embroiled in a similar struggle. In the mountainous northwestern highlands of Guatemala, a few hours drive from the Mexican border, Goldcorp, headquartered in Vancouver, has operated a gold mine for around a decade. The Marlin mine and its industrial facilities are located in San Miguel Ixtahuacán and neighbouring Sipacapa, where Indigenous people live in scattered villages.

Hernández, an elderly Maya Mam woman, is an outspoken opponent of the mine. Like others in the remote region, she subsists on farming. She is in her mid-sixties, and her face is weathered, some of her teeth are missing, and she has one functioning eye—but she has the energy of someone half her age. She describes, in Mam, how her land has been passed down through her family for generations. While others in the region sold off their lands to the mining company, Hernández refused.

In 2010, she says she was arguing with a local leader about her decision not to sell her land when he pointed a machete at her. She was holding her granddaughter in her arms. A while later, two men entered her home and shot her in the head at point-blank range. The bullet entered her right eye and exited her skull near her right ear. She lost sight in the eye and hearing in the ear, and half of her face is partially paralyzed.

When asked about the incident, Goldcorp’s director of corporate affairs, Dominique Ramirez, told me, “In all cases we co-operate with local police for investigations and I’m sure that was the case in this case as well.” After years of pressure from the human rights activist group Rights Action, Goldcorp admitted in a letter that one of the suspected men was a former employee of Goldcorp’s subsidiary and the other worked for a mine contractor.

Yet, despite international and local pressure, the public prosecutor did not advance an investigation into Hernández’s case. Hernández still lives on her property tending to her cows and sheep.

Nearby in the municipality of San Miguel Ixtahuacán, on a warm afternoon early in 2016, nearly forty people from a group opposing Goldcorp’s Marlin mine met to share similar stories. Elderly women in bright traditional Maya clothing, men in straw cowboy hats, mothers breastfeeding their newborns, and children eating mango pops gathered in a building on the outskirts of town. It was the same type of meeting mine opponents have been organizing for over a decade, since the mine began construction in 2004 under the ownership of Canadian mining company Glamis Gold, which merged with Goldcorp in 2006. They spoke of physical attacks, excessive use of force, and kidnapping attempts. In their view, each was the cost of speaking out against the mine.

In 2004, Indigenous communities in San Marcos declared that the mining licence violated “the collective rights of the [I]ndigenous peoples who inhabit our territories.” An Indigenous group in a community 150 kilometres away from the mine then blockaded the Pan-American Highway to prevent equipment from entering the mine. The government response, according to press reports, was to deploy more than 1,000 soldiers and police. Up to twenty people were allegedly injured and Raúl Castro Bocel, an Indigenous farmer, was killed.

A few months later, Alvaro Benigno Sánchez López, a twenty-three-year-old, was attacked and killed after attending a concert in San Miguel Ixtahuacán. Employees of the Golan Group, the mine’s private security contractor, allegedly shot and killed him, then pressured his father not to bring charges. To date, it seems nobody has been charged for either incident, even though Goldcorp’s 2010 independent human rights assessment report confirmed the existence of the killings.

In 2008, Goldcorp started a human rights assessment because of concerned shareholders. The assessment, which focused on Montana, Goldcorp’s subsidiary, found that “because Montana cannot control the actions of public security forces and they have a history of violations of human rights, the company should make every effort to minimize the need for their intervention.” Given the past violence of the civil war, during which state forces and paramilitary groups were responsible for over 90 percent of human rights violations, there is little trust in public security forces, the assessment found. Goldcorp has since implemented the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights.

An organization drawing on communities around the mine presented a report to the Canadian embassy detailing a number of issues with Montana’s behaviour. The embassy received it on March 28, 2012, five years ago. “We did not hear back,” said one member of the group. “We are still looking for justice in our communities.”

On a map of Guatemala, a third Canadian mining site completes a triangle between where Coc Ich and Hernández live, each of them representing disparate places, but similar struggles, across the country. In 2013, in the south of Guatemala, locals had assembled outside of the Escobal mine, to protest the presence of the Minera San Rafael company, a subsidiary of Tahoe Resources, which has ties to Goldcorp. The company’s private security personnel—employed by the Golan Group, the same company used by Goldcorp—allegedly opened fire on them. The head of security, Alberto Rotondo, was caught on wiretaps calling the protestors “faggots” and “sons of bitches,” and discussing the shootings. They fired pepper spray, buckshot, and rubber bullets, according to a legal complaint filed in the Supreme Court of British Columbia in 2014.

Seven men suffered injuries, the most severe being the shooting of eighteen-year-old Luis Fernando García Monroy in the face and back. He needed facial reconstruction surgery.

Rotondo then ordered his men to falsify accounts of the shooting. “We’re saying, ‘Nothing happened here,’” he said. “The version is: they entered and they attacked us. And we repelled them, right?”

In June 2014, seven Guatemalans lodged a civil complaint in Canada for battery. The British Columbia Supreme Court initially dismissed the case because it would be too expensive to conduct the trial in Canada, and Guatemala would be the “appropriate forum.” But with the help of Canadian attorneys Joe Fiorante and Matt Eisenbrandt, the decision was successfully appealed in January. The Court of Appeals found “there is some measurable risk that the appellants will encounter difficulty in receiving a fair trial against a powerful international company whose mining interests in Guatemala align with the political interests of the Guatemalan state.”

Tom Fudge, vice president of Tahoe Resources’s Guatemala operations in 2016, concedes the company made mistakes, but says a lot of the conflict around the mine had been driven by “power plays and efforts at extortion” by local leaders. Fudge, who has decades of experience in the mining industry, believes in the positive impact that his industry can have on communities. “I’m not a monster, but I believe in mining,” he said. In mining, when things are good, “you probably have too easy an access to capital,” he said.

Fudge said the company has always had an active CSR program, which now includes the standards set out in the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, among others. The Canadian government’s CSR program promotes a number of different voluntary frameworks, including those established by the United Nations, the International Finance Corporation, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. According to Fudge, the company’s policies largely align with the Canadian government’s CSR vision, but, he said, following so many guidelines is confusing. “Sometimes I get a little dizzy trying to remember what we are complying with and what’s the difference between them,” he said.

In April 2013, Ambassador Rousseau was photographed with President Pérez Molina as an honorary witness for a royalty agreement between the Guatemalan government and Tahoe Resources in Guatemala City. The signing happened two days after private security officers at the mine allegedly shot and injured the seven locals who later brought the case forward in Canada.

“They have been criminal. How they’ve acted in Guatemala has been criminal,” says Pedro Rafael Maldonado Flores, referring to the role of the Canadian Embassy. As a coordinator of the Guatemalan Center for Environmental, Social and Legal Action (CALAS) he represents communities in lawsuits against Tahoe’s mining operations in Guatemala. He says he heard gunshots outside of his office, had his apartment broken into, and received numerous death threats—so he keeps his security guard close by. In November 2016, one of CALAS’s employees was assassinated (no one appears to have yet been charged for the incident).

In May 2015, Rosa Elbira Coc Ich, Angélica Choc, and German Chub Choc, some of the plaintiffs in the Hudbay lawsuits, travelled to Toronto from Guatemala to address Hudbay’s directors and shareholders at the company’s Annual General Meeting. Angélica Choc shared the story of her husband’s death. “My question for you is: Do you acknowledge the harms suffered by me, Rosa, German, and our families and communities? And what will you do to address these harms?” So far, those calls have not been answered to anyone’s satisfaction—not by the company nor by the Canadian government.

After Coc Ich and her community were evicted from their lands in Lote Ocho, they returned to their homes. They fear more violence, and the ownership of their lands is still in dispute. Despite roughly eight years of reliving her experience before Canadian courts, Coc Ich has said she has little faith in the legal system in Guatemala—a system that evicted her community from the land of which they say they are the rightful owners. Her only chance for justice, she says, is in Canada.

This story was supported by the Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at Columbia University.