The Iqaluit Airport terminal was completed in 1986—two decades after the United States Air Force turned over Frobisher Bay Air Base to Canada. Today it serves Nunavut’s busiest airport, and the city’s only year-round connection to other communities and to the rest of the world. The terminal is close enough to the main drag that Iqalummiuq sometimes pop by just to grab a samosa or two at the Arctic Ventures gift shop or to see who has arrived on the latest First Air flight from Ottawa. Inuktitut, English, and French intermingle inside. It is not uncommon to hear sled dogs barking near baggage claim, which is filled with expedition gear and Rubbermaid tubs packed with goods from the south.

Flying through Iqaluit requires a certain fortitude: The crowded departures lounge lacks sufficient seating, and boarding announcements are muffled by blown-out speakers. Numerous displays with soapstone carvings and ulu knifes showcase local artistic talent, but double as obstacles for strollers, duffle bags, and puffy winter parkas. Phones for taxis are located far in the back, rather than near the exit to the street. A map of Iqaluit, complete with the mayor’s official tourism welcome, is placed near the X-ray machine—handy for those leaving the city but not for those arriving.

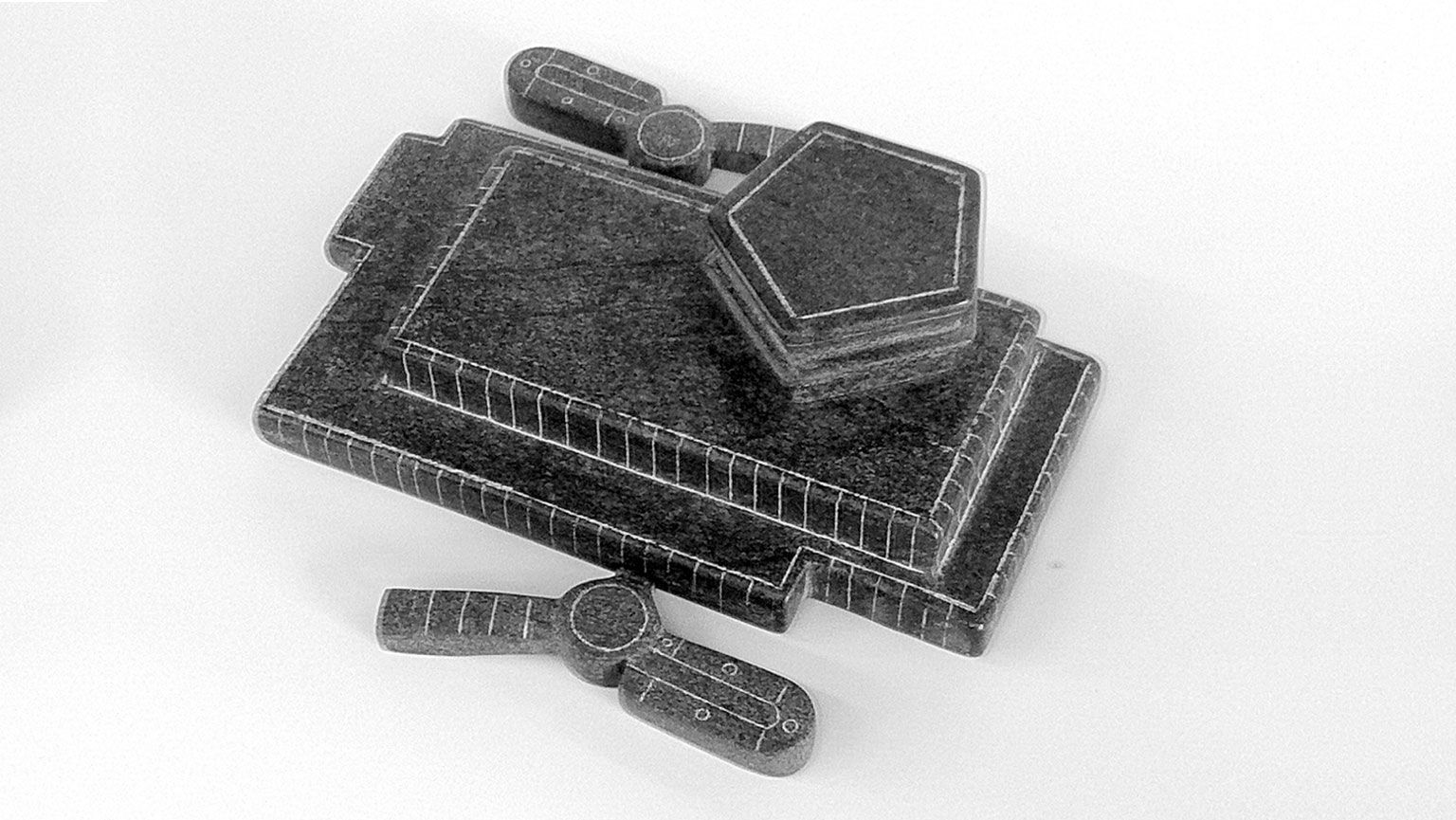

Strip away these annoying imperfections, though, and the subtlety of Iqaluit’s airport terminal emerges. From its proximity to downtown to its bright yellow exterior, it demonstrates how thoughtful Arctic architecture goes beyond ornamentation and acknowledges, indeed facilitates, contemporary Inuit culture. Designed by Alain Fournier, of Fournier Gersovitz Moss Drolet and Associates in Montreal, the building recalls a qaggiq, or communal igloo, with a large central hall and alcoves on the perimeter. Sizeable windows that face the runway and overlook Frobisher Bay, along with skylights above, draw in natural light—an important consideration in the North, and one that many 1970s designs, such as the nearby Nakasuk elementary school, ignore.

The envelope of prefabricated fibre-reinforced plastic panels stands out against the Baffin Island landscape. But the bold hue is far from alien: as Fournier points out, Inuit artists have embraced colours since their introduction in the twentieth century. In a way, the terminal is a Cape Dorset print rendered in three dimensions and set on piles.

The terminal’s construction marked a turning point—the moment when architecture began responding to Inuit realities more thoughtfully than it did in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s. When the landmark opened, passengers praised its clear sight lines and its large central space. The colour earned it the nickname Yellow Submarine. But over time, the original design has been muddled: when Fournier drew up the plans, nobody could anticipate the demands of post-9/11 security or the rapid growth in air traffic. Iqaluit was not yet a capital; the creation of Nunavut was still thirteen years away. As traffic and security measures have increased, those sight lines have been compromised; the large waiting area has been steadily chipped away at by Transport Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency.

The word overcrowded applies to too many buildings in the Arctic—from single-unit homes to marquee projects, such as airports. Last summer, construction started on a larger replacement terminal a little farther down the runway. The expansion, along with runway and apron upgrades, will cost upwards of $400 million in a controversial public–private partnership (the first P3 airport in Canada). But history will not judge Noel Best and Stantec’s new design based on construction budget alone. Does it interact with the street—and pedestrian traffic—the way Fournier’s 1986 building does? Does it celebrate natural light? Does it control snow for drifting? Does it feature inuksuks and igloos in superficial, anachronistic ways, or does it embrace open interiors and driftwood and the realities of modern Inuit life? Does it serve as a community gathering place? These are among the questions that will matter most when the bright red terminal opens in 2017, just as they did thirty years ago.