At the front of a gymnasium, dressed in a well-ironed uniform, my father begins the day’s martial arts seminar with a question: “What is the best form of self-defence?”

In Scarborough, in eastern Toronto, my family held Filipino martial arts classes from April 1999 to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Every Saturday, like a household chore, we assembled our gym, our slice of Philippine life, into being. Setting it up in church halls and community centres during down years, we hauled our large stack of gym mats into the minivan, wedging a bucket of rattan sticks and sparring gear in between. In better financial situations, when we had a lockable office space, all we took was our freshly laundered and starched uniforms: white gi (long-sleeve uniform top), red pants, and belt. For over twenty years, our gym was an extra wing of our home, reaching out from the front door to an archipelago of martial artists across the city.

My father’s students, young and old, comprise its islands: Filipino, Tamil, Jamaican, Palestinian, Chinese, Syrian, Nigerian, and more. They gather in this makeshift dojo, starting their afternoons with stretches and calisthenics. After a short break, the students reassemble and wait in anticipation for their instructor’s wisdom. At the front of the class, my father repeats his question: “What is the best form of self-defence?” A few seconds of confused silence until a student raises her hand.

“Is it to disarm your opponent in as few moves as possible?”

My father smirks and beckons me. “Anak, come,” he says, using the Tagalog word for “child.” I walk to the front of the class and stand next to him. “Any hold or lock you want.” I stand behind him and wrap my right arm around his neck, locking it in place with my left hand—a “sleeper hold.” He tucks his chin down, into my elbow, to give himself breathing room. “Sure, let’s do it in two moves,” he says in a muffled tone.

“One—” He grabs hold of my elbow joint and my left hand and steps to the left. He sways his waist left and locks his right hip behind my left. I stumble forward, and my arm is no longer wrapped around his neck.

“Two!” With a flick of his hip and a heave over his shoulder, he disarms me and drags me along the ground. All of a sudden, my body is supine and I am facing the ceiling as my right arm is caught in a pressing lock. I feel a sharp pain in my right shoulder and tap the floor with my left. He releases and helps me up. We catch our breaths. “Good, but that’s not quite it.”

At the behest of the students, we demonstrate other locks: bear hugs and other wrestling moves, manoeuvres with knives, swinging sticks. When I am tired, he brings forward other volunteers: burlier men who tower over his five-foot-seven frame. After several attempts and through heaving breaths, he finally stops and addresses the class.

“Those are all good moves. But there’s one technique that none of you have talked about yet.” He beckons me over again. I hide a grin, because I know where this is going. “Come at me with the same technique you did first,” he says. I lunge forward, ready to subdue him in a sleeper hold.

He sprints away.

The class is uproarious. The younger students roll on the floor, laughing and wheezing. My father turns around and makes his way back to the front of the class.

“Running away. That’s the best self-defence.” A few students nod as his lesson clicks into place. “Or, better yet, do everything you can to not be in that situation in the first place. If you find yourself in these sorts of situations, avoid it entirely. If you don’t have to fight, don’t. Only as a last resort.”

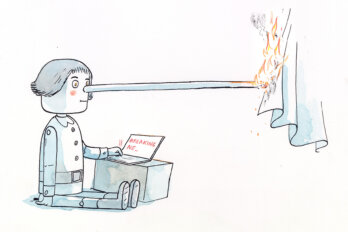

But, I thought, what if you can’t run away?

On March 11, 2022, in Yonkers, New York, a forty-two-year-old man bludgeoned a sixty-seven-year-old Filipina woman over 125 times a few paces from her apartment, according to the New York Times. She couldn’t run away. Almost a year prior, a twenty-one-year-old man in Atlanta, Georgia, armed with a 9 mm handgun, stormed into three massage parlours and killed eight people, six of whom were women of Asian descent. They couldn’t run away. And, in early 2020, when the United States was still weeks away from a national lockdown, an elderly man in San Francisco was collecting recyclable litter when he was beaten violently and robbed of his belongings while a man filmed and ridiculed him. He couldn’t run away.

Between March 2020 and March 2022, according to a report by Stop AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islanders) Hate, a US nonprofit, there were over 10,000 reported cases of anti-Asian violence in the country. In Canada, according to the Toronto chapter of the Chinese Canadian National Council, in addition to the 47 percent rise in racism against East Asians, other groups, especially South and Southeast Asians, have found themselves in the strike path of anti-Asian violence. Some ran, some defended themselves, and some couldn’t do anything at all. And, because they were Asian—specifically, Asian women and elders—racists found them to be easy targets.

Martial arts work, first and foremost, at the individual level. You train yourself to be agile and strong, practising manoeuvres and movements until they become second nature. Then, you learn how to apply those techniques through simulated combat scenarios such as sparring matches and competitions. You progress through the ranks, refining your skills and mentoring your juniors, until, at last, you receive your black belt: the pinnacle of traditional martial arts ranks.

But the final goal of martial arts isn’t the black belt, nor is it any of the various tournament accolades you might earn along the way. The goal of martial arts is to practise self-defence. And this does not mean protecting only yourself. According to one of my father’s many adages, “Self-defence means to protect yourself, to protect others around you, and to protect your opponent from committing a crime.” Self-defence, which comes out of practices like martial arts, is an ethical responsibility to keep yourself and others safe. What does self-defence mean, then, when the violence against your communities isn’t an acute condition but is as atmospheric as racism itself?

Martial artists, especially those from the Philippines, became highly coveted for two reasons: their proficiency in English and their close-combat skills. With the exception of Dan Inosanto (a student of the legendary Hong Kong–raised martial artist and film star Bruce Lee), hardly any Filipino martial artists made it to Hollywood screens. Instead, many became choreographers and instructors. The most seasoned practitioners, such as the Mindanawon great grandmaster Carlito A. Lanada, found employment teaching his family’s styles to the Philippine and American militaries. As an English-speaking combat educator, he was able to immigrate to the US and continue his work training members of the armed forces and went on to establish a major martial arts academy. Forty years later, he befriended my father and gave my family his blessing to take up his style as one of our featured arts at our gym.

I loved my adopted lolo (grandfather), but the violent underbelly of his route to the US was hard to shake off. Teaching our cultural arts to soldiers, military officers, and some who would go on to become police officers is not virtuous. It means that Filipino martial arts have become part of the machinery of death that brutalizes Black and Brown people in their neighbourhoods, occupies stolen lands and displaces Indigenous peoples, and wages wars all over the world. But, recognizing the political and economic conditions of the Philippines at the time, this might have been one of lolo’s few ways of finding a better life for his family in the tumultuous aftermath of the Second World War. I just wish it didn’t happen this way.

Some of my father’s former students who had enrolled as teenagers went on to become soldiers. A few others expressed their desire to enter the police force—though it wasn’t clear if they ever did. But my father seemed to have a different mission in mind. He told me stories about his years in the Manila slums, where a local gang would bully him and other neighbourhood youth. Frustrated with the constant targeting, he taught his friends basic martial arts techniques that he had learned from his own father. Then, once the rival gang arrived to bully them, they could all fend for themselves and maintain order in the neighbourhood.

When my father left the Philippines to work in Saudi Arabia, he found a wider athletics community with other overseas Filipino workers. There, he learned many more styles, and in addition to becoming a bodybuilder, he quickly rose through the ranks as a regular tournament champion. He would send back photographs and medals that he earned in his competitions. As he was abroad when I was born, the first pictures of him I saw were ones where he is in his uniform, heel raised, about to strike at his opponent’s chin.

When I began to meet the rest of my father’s family, both in the Philippines and later in the US, they let me in on their stories about him. As it turns out, he was always a sickly boy. Of all his brothers and sisters, he was often teased as the least athletic one. I think about what it might have been like to be frequently bedridden, yearning for the ability to protect oneself. His father, a major patriarch in the province of Bataan, would teach him the basics of bladed-weapon styles until the son became proficient. Unfortunately, my grandfather was also a traumatized former guerilla fighter from the Second World War. At times, he could resort to violence. In an almost indiscernible tone, my father would tell me how my grandfather chased him around with a bolo (machete) or beat him with a wooden rod.

In his brief visits to the Philippines, when my mother and I still lived in a Manila compound, my father would bring me up a ladder to the concrete roof of our house. There, he would hand me a rattan stick and demonstrate a sequence of twelve strikes (doseng hataw) and their corresponding counterattacks. I don’t remember much he said to me as a child, but to this day, I can still wield any makeshift weapon and execute those blocks and strikes. Likewise, when he wanted to seek retribution or punish me for some misdeed, the rattan stick—or, more commonly, his belt—served a different purpose altogether. In the absence of a shared language and experience, my father spoke to me in the only way he knew to speak with his faraway son: violence.

As an overseas Filipino worker in Saudi Arabia, he gained access to the kinds of incomes that never could have been available if he had stayed home. My mother found a job in middle management at a tech company. But, even with these salaries, the money stretched thinner and thinner every year. Fresh from the unfinished revolution of 1986, during which the dictator Ferdinand Marcos was deposed in favour of a Christian nationalist president, the Philippines was (and continues to be) ravaged by the plundering authoritarian regime. Fidel V. Ramos, who succeeded the post-Marcos administration of Corazon Aquino, is said to have been one of the most economically successful presidents in recent memory. But the benefits never trickled down to the slums of Taguig district, where we lived. We could never afford better housing, nor could we fund a lifestyle in the Philippines in which both of my parents could live together and raise me as a couple.

We can’t run away from something atmospheric. And I think my parents knew that. So we left the country.

When we moved to Canada, in 1998, we packed very few things with us—but my father made sure to ship all of his trophies and belts. Those accolades accompanied us everywhere we lived: a jaundiced basement apartment, a two bedroom with crumbling doors, a townhome, and our house on a corner lot. They followed us across gyms, too, except when we needed the occasional community centre or public park in between more permanent locations.

Our martial arts gym in Scarborough had been open only a few short years when the deadly SARS outbreak tore through the city in 2003. And, as we shut our gym, many of the families in our gym got to work in isolation wards. According to a 2004 study by sociologist and novelist Carrianne Leung, health care workers, many of Filipino and Chinese descent, reported increased experiences of hostility and outright violence between work and home. For Asian people and other people of colour, commuting became even more of a dangerous affair than it might have already been, even as the city celebrated their contributions in hospital wards. The women in our community felt these threats were pronounced.

Shortly after SARS cases began to subside, my father brainstormed ways to improve the women’s curriculum at the gym; in the years that followed, the number of women with black belts, all of whom were women of colour, boomed. At home, my father began to urge my mother (who eventually went on to earn her black belt) to work with the class on her techniques.

Sometimes I reflect on my father’s adage. Self-defence is not just about protecting yourself and others but also about protecting your opponent from committing a crime. When I was younger, I was often frustrated with how friendly my father was around police officers. He knew how to act suavely around a cop and shift his accent to sound as white as possible. Even when he was pulled over for speeding, he always recounted the moment as one in which the officer was only doing their job. Many years later, I now understand that acquiescence to be self-defence. I think, deep down, and despite his stating otherwise, my father knew that the police wouldn’t save us either.

One afternoon, when I was nine years old, my parents returned home with a shell-shocked look on their faces. Before I could ask what had happened, my father declared: “Your kuya Jeffrey was killed by the police.” This kuya (older brother) was Jeffrey Reodica, a seventeen-year-old Filipino teenager in our church community. Toronto police officer Dan Belanger shot him three times in the back. Belanger later gave the excuse that Jeffrey seemed to be brandishing a knife.

In our Saturday seminars, my father mulled over the killing with his older students. I, still a child, sat in the circle, trying to absorb everything they were saying. I think my father wished that Jeffrey had been in his classes. But he couldn’t have defended himself from the police. At least not in the way that martial arts teach you.

Someone asked if, maybe, Jeffrey could have made it more obvious that he wasn’t holding a weapon. But, from the news reports and eyewitness accounts, it was clear to us that he was unarmed. Then, under their breath, someone uttered: “Damned cops.” I think it might have been my father, but swearing was forbidden. Ontario’s Special Investigations Unit cleared Dan Belanger soon after. Today, the officer is a free man.

Over fifteen years later, in broad daylight, two young women followed my lola (grandmother) on the street with the intention of assaulting and robbing her, should they have the opportunity to do so. Oblivious to her surroundings, lola walked on in her slow and elegant gait toward our home. My father opened the door, brought my grandmother inside, and reprimanded her would-be assailants. The women did not deny their intent. Instead, they threatened my family with retribution.

By then, I had long moved out of my parents’ house. My brother told me that something almost happened to lola, so I called home. “Did you call the police?” I instinctively asked.

“We did,” my mother answered, “but, of course, they won’t do anything.”

After that, lola could no longer leave home without supervision. My brother or one of my parents or one of lola’s friends would have to be with her. The next time I visited, I opened the jacket closet and moved the hangers aside. I noticed the far corner was lined with rattan sticks and sheathed blades.

The only shared language between my father and me was martial arts. We rarely practised together because we would probably end up arguing. But we shared in our love of teaching and the students’ progress and, at home, often watched action movies together. Beyond combat, we had little else on which to build our relationship. And so, when the COVID-19 pandemic locked down all social and community life, my parents closed the gym. There’s hope it may reopen someday. A year later, after a string of arguments, my father and I stopped speaking.

During my time away from Toronto, in the two years after the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, and in an era of heightened anti-Asian violence, I’ve carefully reflected on my father’s words and his practice, even as his body can no longer sustain any sort of long-term physical activity. In 2021, as the cases of anti-Asian violence in cities like New York, San Francisco, and Vancouver rose, Asian American business owners called for investments in police protection and private security forces. Local police departments, such as in San Francisco and Toronto, took these as an opportunity to expand despite the calls from activists under the Black Lives Matter movement to defund or abolish their forces. This was, perhaps, a twisted form of self-defence—but one that depended on a system built to oppress and control Black people and other minorities. This kind of self-defence, then, is not the answer.

In the twenty years I spent under his tutelage, my father taught me through his practice that it was my responsibility as a martial artist to defend myself and others. If self-defence is the ethic that martial arts teach, can we scale that up to the level of a community built on genuine safety and mutual care?

The assailant in Yonkers was a Black man. Unhoused people also counted among the attackers of Asian women over the past year. My grandmother’s would-be assailants were Black and white women. And my father, the community leader that he was, only knew how to raise his children through physical and emotional abuse—vestiges of his own childhood. But, despite this, an ethic of vengeance—even against those who hurt you, especially when they, too, are marginalized—is not the answer, especially if self-defence is supposed to be a communal project.

In the intellectual history of the idea of self-defence, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale of the Black Panther Party were among the greatest thinkers. As theatre scholar Danielle Bainbridge once told me, Newton and Seale’s original name for the party was the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. Their Ten-Point Program advocated for the redistribution of resources and safety for Black and oppressed peoples worldwide, an end to their involvement in wars abroad, and housing and livable wages for all. Theirs was a vision not only for individual self-defence but also for a capacious and embracing first-person plural—a platform for a collective we from which we could build a life-sustaining future.

Whenever I think about what self-defence means today, I think about my father’s other job as a martial artist: teaching. One of Newton and Seale’s ten points was the right to a political and antiracist education against white supremacy. In my profession, we often credit their work and the organizing of the Third World Liberation Front activists in 1969 and 1970 for the creation of the classrooms of our various fields—including my own, Asian American studies.

Above all else, my father was a prodigious teacher, with unparalleled patience for students of every background. When faced with a timid or struggling student, he seemed to pull a curricular solution out of thin air. Even when challengers from other gyms came to see what he was all about, in an effort to undermine his work, he could turn their visit into a teachable, and often humbling, moment. And the legacies he has left behind are his students, who have become competitive martial artists in their own right and entered the various professions and arts practices that make up Toronto’s cultural life.

In all honesty, I was never any good at martial arts and rarely placed in any of my competitions. But I at least knew that, like my father, I loved teaching. As a professor of ethnic studies, I can’t run away from the fight, especially when the fight is about the continued existence of social justice spaces like my classroom, like my father’s. There is no running in self-defence—and no running from frequent harassment and death threats—when the ideas we speak about are as atmospheric as racism itself.