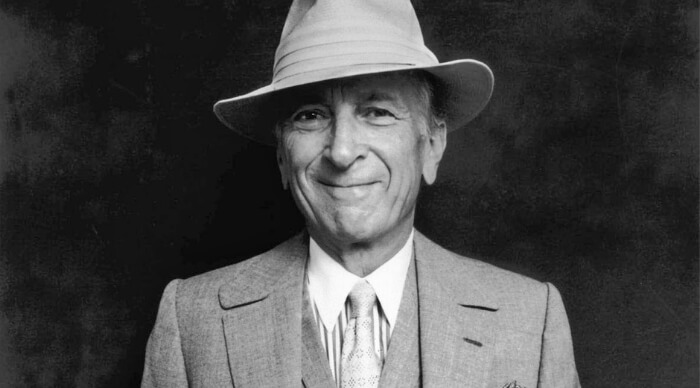

When the Washington Post presented Gay Talese with inconsistencies in his new book, The Voyeur’s Motel, Talese had an astonishing reaction: “I’m not going to promote this book,” he declared. “How dare I promote it when its credibility is down the toilet?” The Post’s story ran under the headline “Author Gay Talese disavows his latest book amid credibility questions.” Just one day later, however, the author backed off: “Let me be clear,” he told the New York Times, “I am not disavowing the book.”

Had he stuck to his initial reaction, The Voyeur’s Motel would be the year’s most high-profile entry into a peculiar literary genre: repudiated books. While Talese’s disavowal was seen as desperate, in fact he would’ve joined an illustrious list of authors who have jettisoned books from their oeuvres, including Ivy Compton-Burnett, Don DeLillo, and Anthony Burgess.

By repudiated books, I don’t mean the great many burned manuscripts whose particles float in the air around us. Rather, I mean books that have gone through the entire cycle of composition, publication, and reception, only to then be metaphorically burned by an author’s repentance.

These books are the orphans of literature. Or perhaps they aren’t orphaned so much as disinherited. After all, they weren’t published anonymously; the author’s identity is known. What’s happened instead is a breach of contract. Conventionally, author and book share a vaguely defined but indissoluble bond. The author accepts the book’s fate as his or her own, and whatever comes—praise or outrage or indifference—is ultimately measured as the artist’s success or failure. A repudiated book, on the other hand, has had its fate severed from the author’s. It drifts through literary history, bearing the mark of rejection.

Repudiation can be prompted by a change in the author’s personality. The English poet Rosemary Tonks (1928–2014) disavowed her entire corpus as “dangerous rubbish” when she embarked on what became four decades of spiritual seclusion. As Neil Astley wrote in her obituary: “She followed Rimbaud in renouncing literature totally, believing that Proust, Chekhov, Tolstoy and French 19th-century poetry had carried away her mind.” But the change can also be material. May Hutton (1860–1915), an influential suffrage leader in the Pacific Northwest, wrote a libelous novel about the poor treatment of Idaho miners. In later life, when she became a wealthy mine owner herself, she tried buying back every copy.

Most of the time, however, authors repudiate out of self-preservation. In the case of journalism like Talese’s, disavowal serves as a drastic remedy to heal credibility. By rejecting his or her own book, the journalist stands, albeit on wobbly legs, in defence of journalistic principles. When a creative writer repudiates a book, however, more nebulous principles are at stake. The standards by which artists judge themselves are private, undefined, often contradictory. Artistic repudiation has little to do with the public; rather, it serves as a kind of self-healing.

Disavowed novels are often associated with immature artistry, and so repudiation functions as a way of quarantining what an author defines as serious work from his or her apprenticeship. Consider it a literary cleanse. According to his publisher, Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864) spoke of his first novel, Fanshawe (1828), “with great disgust,” and suggested that it would be mutually beneficial “to conceal it” along with “other follies of my nonage.” Ivy Compton-Burnett (1884–1969) simply omitted her first novel, Dolores (1911), from her list of publications. “Apparently even its author did not want to remember it,” read the dust jacket of an edition published after her death (it has since fallen back out of print).

Like the best assassinations, literary disavowals tend to happen silently, in the manner of Compton-Burnett’s neglect and omission. But sometimes authors stab their books right in the front. In a letter to Henry Miller just a week after its American publication, George Orwell referred to his 1935 novel, The Clergyman’s Daughter, as “bollocks,” while Graham Greene, who disowned two novels—The Name of Action (1930) and Rumour at Nightfall (1931)—had this to say in his memoir: “Both books are of a badness beyond the power of criticism properly to evoke.”

Some writers take a more indulgent view of their follies, while still effectively distancing their mature and immature work. Due to the wishes of his estate, Nothing But the Night (1948), the first novel of Stoner author John Williams (1922–1994), has been omitted from the hugely successful reissues of his work. Although Nancy Williams, his wife, wrote to me that “‘repudiate’ is too strong a word to describe John’s attitude toward Nothing But the Night,” nevertheless, as she recalls, “His student, the novelist Michelle Latiolais told me that John once said to her ‘I didn’t write that novel.’ Laughing, of course.”

What’s the sensation of reading a repudiated book? I first became interested in the genre after finding a copy of Amazons (1980) by Cleo Birdwell. “An Intimate Memoir by the First Woman Ever to Play in the National Hockey League,” Amazons traces the life of Cleo Birdwell over the course of a season with the New York Rangers.

Ever since publication, it has been an open secret that the novel was actually written by Don DeLillo (along with a collaborator). The true author is hiding in plain sight: every page of Amazons crackles with a lighter, less consequential version of DeLillo’s distinctive wit. Yet he’s remained silent about his authorship. Amazons has never been reprinted, and when his official bibliography was compiled, DeLillo asked that it be left out.

The experience of reading Amazons felt almost illicit. Perhaps not even reading an author’s letters, or a posthumously published novel, goes more overtly against their wishes. Though I’ve always believed that the Death of the Author has been greatly exaggerated, reading a repudiated book did indeed feel like a triumph of reader over author. I was in possession of a stolen good. This same penumbra shades all of Kafka’s work, which he ordered to be burned, and it’s worth asking whether the Kafkaesque sensation—trespassing in a hermetic world—is partly informed by our knowledge that everything we read was repudiated.

Enjoying one of these books, as I did with Amazons, puts the reader in an even stranger position. For when the book is genuinely bad, the reader can join the author in condemnation; they share an inside joke at the book’s expense. But what to do with all this praise? The bond between author and work has been broken, and so it feels inappropriate to lavish him or her with accolades. After all, if you don’t acknowledge a child, you don’t have to change its diapers; but neither do you get any credit if they grow up to be president.

Anthony Burgess (1917–1993) ventured a most daring repudiation, when in a 1985 study of D. H. Lawrence, he wrote: “The book I am best known for, or only known for, is a novel I am prepared to repudiate.” He was referring to A Clockwork Orange (1962), and thirty years later, his complaint is only truer. While I know fans of Earthly Powers (1980), and am myself an admirer of his novel about Shakespeare, Nothing Like the Sun (1964), it’s hard to disagree that his legacy is inextricably tethered to A Clockwork Orange; in many quarters, he’s synonymous with it. By repudiating the book, Burgess risked the annihilation of his name—all that praise, voided. But in the end, sheer popularity prevented him from effectively disavowing it, perhaps why he was only ever “prepared to.” A Clockwork Orange became his Frankenstein’s monster, if the monster turned out to be beautiful and congenial.

By and large, however, the reading public tends to allow repudiation. At a time when even the most off-hand remark can haunt an individual forever, we demonstrate an odd generosity toward artistic disavowal. Simply at his or her request, we relieve the author of the burden of hundreds of thousands of ill-conceived words. No one holds Octavia Butler accountable for Survivor (1978), or John Banville for Nightspawn (1971). Why? Is it because fiction, even at its best, is considered part of a general flow of unmeant phrases? We’ve all said something we regret. I suppose the trick is not to be taken seriously in the first place.