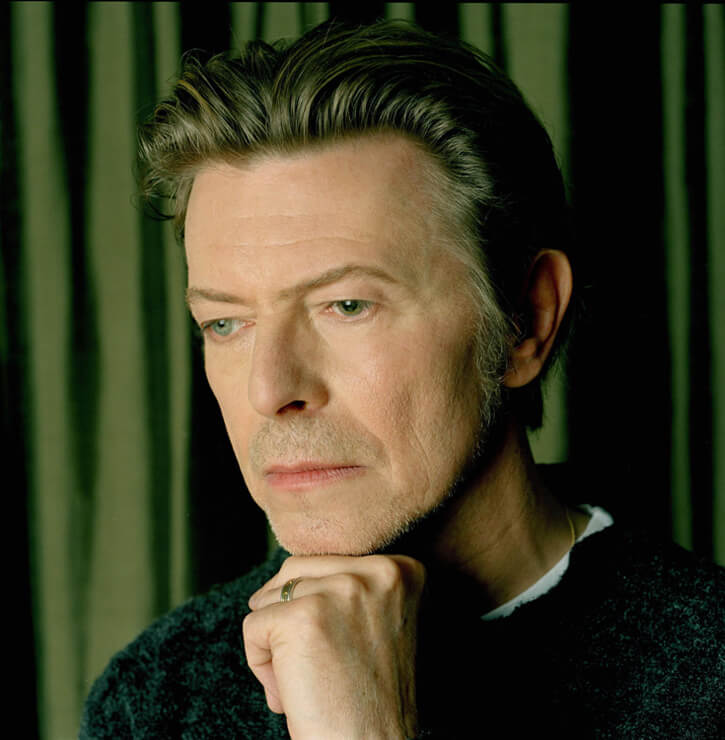

David Bowie was pop culture’s great chameleon—performing a bewildering number of phase shifts in his music, art, and sex life. But his defining legacy always will be the run of albums he created in the 1970s, and their recurrent, haunting themes of tragedy and heroism. These are subjects that endlessly obsess the adolescent mind, and no musical artist of my era wove them together as exquisitely as did Bowie. The noble loners he conjured—Ziggy, Major Tom, the mythic “we” of Heroes, the puzzled man and the Golden One—became sources of inspiration for millions of desperately sensitive young teenagers. Including this one.

It was my high school friend Greg who introduced me to Bowie. We were in our early teens, playing board games in his basement, both of us on the awkward fringes of mainstream social life. At the time, we often listened to British alt-rock songs about the decline of small, dreary northern towns, and analyzing the postmodern lyrics of Talking Heads and other art-house bands. At one point, I became obsessed with Bauhaus, declaring myself a Goth for about a week and a half. I had nothing but contempt for the Iron Maiden-led heavy metal surge that was sweeping Canadian high schools—which I associated with tacky acid wash and self-parodic, medieval-themed airbrush art.

And yet metal had something that every fourteen-year-old craves: a sense of the heroic. (“One important point to be made when discussing [Iron] Maiden’s so-to-say “historical” songs it that they highlight both the deeds of great heroes,” notes one scholarly researcher. “The aggressive and grandiose musical features of Heavy Metal have an undeniable epic element that lay the ground to treat war conflicts, in all of its configurations.”) None of the New Wave stuff I was listening to delivered that. Instead, it was all about detachment, alienation, satire, nihilism.

This is the ennui-shaped hole that Bowie filled in the inner lives of teens across the Western world. He was an intellectual and a Brit, and he never wore bad denim. His music accomplished the role of true art—it haunts you with the need to think—even when it had no words, as with Speed Of Life. Yet it also was populated with men who stood heroically on the cusp of cosmic change.

Typically, the change was apocalyptic (think Five Years or Oh You Pretty Things). But the heroes themselves weren’t nihilists. Nor crude flaming-skull Sympathy for the Devil anti-heroes. All of them were destined for a tragic end, striking noble poses on the edge of Armageddon. (I, I will be king / And you, you will be queen . . . We can be Heroes, just for one day.) But they had, in their lyrical moment, a majesty that brought to mind the English Romantics that Greg and I were being taught at school. It was intellectual yet not arid, rhapsodic yet not maudlin.

There was a very modern social message, too—even if it wasn’t one Bowie focused on explicitly. His whole life was a species of performance art, one that playfully warped all the traditional gender role-modelling that I’d been taught (and that often was reinforced, to a ludicrous degree, in rap, heavy metal, and arena rock).

Yesterday, when Ricky Gervais was panned for making a dumb joke about transgenderism at the Golden Globes, commentators opined that this might finally be the death knell for this type of dehumanizing humour. From Lady Stardust to Rebel Rebel, Bowie arguably was more than four decades ahead of the curve. And I thank him for opening my mind to a world of pretty things.