If the British North America Act were being written today… natural resource ownership would most likely remain with the federal government.

Todd Hirsch, Policy Options, October 2005

It should have been a lovefest. Leading up to the Alberta Progressive Conservative Annual General Meeting on March 31, 2006, polls declared Premier Ralph Klein the most popular man in the province, and for good reason. Other provincial governments, an expert panel appointed by the federal Liberals, and even the Governor General recommended that Alberta share its bountiful riches with the rest of Canada. In response, the tough-talking premier said, essentially, “over my dead body.” It was classic Klein.

For years the premier had been Alberta’s chief defender, and his record was impressive. He led the PC Party to four consecutive majority governments, enjoyed better than 90-percent approval ratings in previous leadership reviews, and could boast of an enviable series of accomplishments. In 1993, Klein inherited a government bleeding $3.4 billion a year and with an accumulated debt of $23 billion. Thirteen years on, Alberta is Canada’s only debt-free province, its budget surplus hovers around $11 billion, and the populist premier can justifiably lay claim to having created the “Alberta Advantage.”

In the last quarter of 2005, the population of seven provinces or territories shrank, while teeming thousands migrated to Alberta. They were drawn by the lowest unemployment rate in Canada and a combined municipal and provincial tax rate that is 45 percent below the national average. In Alberta, with no sales tax and plummeting provincial taxes, a typical two-income family earning $60,000 pays roughly $4,000 for health-insurance premiums and one-third less in provincial income, gas, and tobacco taxes than the mean across Canada. Less tax means more take-home pay, and in the event that this typical couple has children, they can be confident their kids will receive top-quality education: grade ten students in Alberta routinely record the nation’s highest reading, math, and science scores.

Alberta’s advantages are destined to become even more dramatic. While other regions struggle to meet the escalating health-care costs of aging populations, 57 percent of Albertans are under forty—the highest percentage of young people in Canada. Albertans already generate Canada’s most robust per-capita gdp, and per-capita investment in Alberta is more than double that of the next-highest province. Relative to population, Calgary has twice as many corporate head offices as Toronto, and with business growth almost four times the national average, the Edmonton-Calgary corridor has become the most productive region in North America. While snobs in Ontario might cling to the view that Alberta is still home to uncultured rednecks beholden to the boom-and-bust energy sector, the truth is just the opposite. Increasingly, the province’s rapid growth is fuelled by a highly sophisticated workforce. Over 60 percent of Albertans have university or college educations, Internet use is the highest in Canada, and service industries—everything from restaurants to communications—now account for roughly 60 percent of the provincial economy.

Against this backdrop, at the Tory Annual General Meeting, Klein requested that he control the timing of his departure from politics. Instead, in an expression of non-confidence, nearly half of the delegates voted him down. How did this happen?

Klein may have been “shocked… and a little hurt,” but signs that he might be so humiliated had been appearing across the province for some time. Ten days before the vote, leadership front-runner and former provincial treasurer Jim Dinning spoke to the Meadowlark PC Association and warned that “as much as geology and geography have provided us a rich gift, it is just that, a gift. It is meaningless unless we do something with it.” Dinning was referring to Alberta’s unprecedented natural-resource wealth from oil-sands developments, and he insisted that prosperous times were no occasion for complacency. Alberta had to dream big, he said, and show a talent “not only for taking the resources out of the ground, but going the next step.”

Days later, former Conservative premier Peter Lougheed entered the fray with an op-ed in the Globe and Mail. If Dinning reserved his comments mostly for provincial imperatives, Lougheed went after bigger game. With Klein and others defending Alberta’s right to keep energy royalties at home—and conjuring up the last time Ottawa made a power and money grab for Alberta’s natural resources, the infamous National Energy Program (nep) of the early 1980s, to bolster their case—Lougheed suggested a more magnanimous approach. Alberta, he said, should remain in charge of its riches, to be sure, but in the name of national unity and the province assuming a lead role in the federation, it should also invest in Canada.

Lougheed might credit Klein, to date at least, with dealing adequately with the province’s surplus revenues—after all, Alberta spends significantly more than the national average on education, culture, and industrial development, and its research grants far outstrip those allotted elsewhere (the province has just created a $500-million cancer-research fund)—but like Dinning, Lougheed believes that Alberta is facing a pivotal moment and that it must prepare now for the future.

Just before the Tory meeting, David McColl, the president of the Young Albertans’ PC Association, brashly asserted that Klein had “absolutely no vision” for Alberta. The premier’s sin was rooted not in his past record or in his sometimes erratic behaviour, but in his lacking the urgency and wherewithal to transform Alberta’s “advantage” into something more meaningful than riches and good fortune. According to Tory insider Ken Hughes, the rebuke Klein experienced on March 31 had far less to do with the naked ambition of leadership hopefuls wanting an early convention than with a profound sense that if Alberta stood pat its future was in peril.

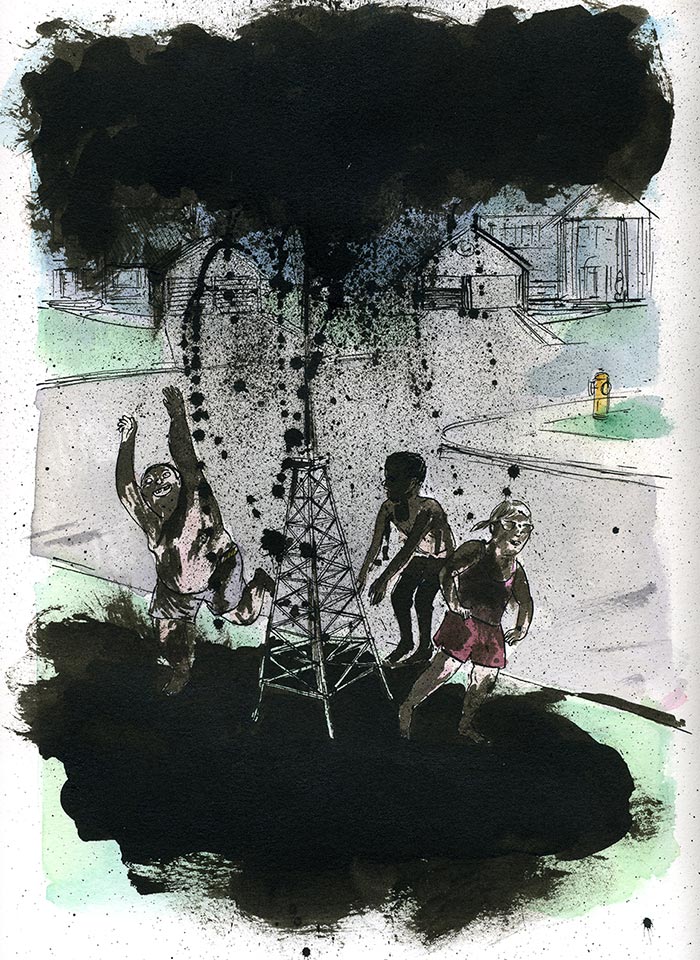

While most Canadians are aware of Alberta’s resource wealth, few appreciate the complications created by a large and regular annual surplus. Alberta is blessed with two-thirds of the country’s reserves of conventional oil, over 80 percent of its natural gas, and the bulk of its coal supply. Historically, this resource richness has been a mixed blessing. As prices fluctuated, Alberta experienced untenable booms and busts. Today, with crude-oil prices set high and likely to remain so, the industry’s success is generating repercussions that are proving difficult for the rest of the economy to absorb. Rapid growth in the energy sector has led to rising labour costs across the province, soaring real-estate prices, and other inflationary pressures. These fiscal realities make it difficult for small- and medium-sized businesses (outside of the resource sector) to compete. With employees constantly seeking better pay and better conditions, staffs and work crews are anything but stable. Welders snapped up by high-paying oil companies are not available for work elsewhere, and a good number of companies cannot meet their orders or production quotas. A surprising number are losing business to outside competitors, and some are closing their doors.

Other problems—such as “virtual residents” filing tax returns using Alberta addresses—are evident, but the big issues remain the labour shortages and runaway costs that are driving up prices and might result in hyperinflation. While the mood was joyous at the Calgary Stampede in July, the weather did not co-operate, and a certain pall was cast on the festivities when energy stocks took a hit after news that cost overruns could stall oil-sands expansion projects.

Such worries aside, a growing economy is a demanding one, and simply saving for the future is not an option. Alberta must do something with its surplus cash, and, according to the Canada West Foundation, a Calgary-based think tank, that something will generate “the most important debate that Albertans will face for a generation. It is also one that will ripple across the West and across the country.”

Beyond the headlines and a wave of high-profile energy-sector promotions—including displays of the gigantic oil-sands trucks for US senators and investors in Washington—Alberta has actually done a remarkable job insulating itself from a dependency on natural resources. The energy sector’s contribution to Alberta’s gdp dropped from 36 percent in 1985 to 23 percent in 2002, and despite growing pains the province’s triple “A” credit rating (the only such rating granted to a Canadian province by the major investors’ services) is based largely on its diversified economy. The question, says Roger Gibbins, president and ceo of the Canada West Foundation, is whether Alberta’s current fiscal position is sustainable. “My suspicion is that it is,” he told me last spring, his optimism resting on demand for Alberta crude from the United States and the emerging markets of China and India.

The US is “addicted to oil,” as President Bush put it—bad news for climate change, perhaps, but great news for Alberta—and Gibbins believes that the province is “relatively immune to any downturn in the US economy and to the border-security issues that pose risks to [Ontario’s] manufacturing base.” Indeed, with the supply chain from the Middle East, Venezuela, and Russia uncertain, cibc predicts that Alberta’s reserves “will be the most important source of new oil in the world by 2010.”

Echoing the point, in mid-July at the G8 summit, with the Middle East erupting in war and Russia sounding the wrong notes about foreign direct investment, Prime Minister Harper boldly declared Canada an emergent “global energy superpower” with secure supplies and a commitment to open markets. He was clearly thinking of Alberta.

Alberta’s rise to economic prominence coincided with the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement and, more specifically, to stipulations in nafta that assure the US a steady supply of oil. Alberta’s pipelines tilt decidedly north-south, and almost two-thirds of its oil and gas exports flow south of the border—compared to 14 percent of its oil and 24 percent of its gas shipped to sister provinces—helping to make Canada the largest supplier of energy to the United States. Some Canadians may bristle at this sweetheart arrangement, but given Harper’s views about provincial rights and positive relations with the US, the situation is unlikely to change.

The oil sands cover 140,800 square kilometres, an area the size of New York State, and contain roughly one trillion barrels of bitumen, from which 176 billion barrels of oil is considered recoverable. Buried in muck and muskeg, the northern-Alberta reserves weren’t economically viable for decades as low energy prices discouraged investment in research and development. When prices reached $30 per barrel, the tide shifted, and extraction looked considerably more promising. The chief difficulty was the enormous capital costs required. To address this, in a move that now seems either clairvoyant or foolhardy—polls indicate that a plurality of Albertans believe they are receiving “less than they deserve” from the oil sands, and many want the deal reopened—the Alberta government stepped in with a very generous royalty arrangement. Rates were set at a mere 1 percent of production and would increase only when the participating companies recouped their development costs.

That moment is fast approaching. With oil prices hitting $78 (US) a barrel and likely to remain high, and production scheduled to double to over four million barrels a day by 2015, a financial bonanza is on the horizon. Whereas in 2005 Alberta generated $14.3 billion in non-renewable resource revenue and the government received $950 million in oil-sands royalties, in ten years total revenues will likely be off the charts. Oil-sands royalty cheques are projected to top $5 billion annually.

For the 2005-06 fiscal year, Alberta has a reported budget surplus of $8.7 billion, higher than the federal government’s budget surplus of $8 billion. Alberta’s $8.7 billion, however, is over and above unbudgeted spending of $2.5 billion, including the $1.3 billion in “prosperity cheques” forwarded earlier this year to every man, woman, and child resident in the province. Since 2000, the Alberta government has increased its program spending by roughly 10 percent each year. The cumulative result is impressive, but now, to keep people and attract others, the provincial government can spend like a drunken sailor, build an extraordinary asset base, and lower taxes even further.

The only thing limiting Alberta’s expansion is legislation capping the amount of non-renewable resource royalties that can be put into its program expenditures (the current maximum is $4.75 billion per year). Essentially, this self-imposed constraint demands that the provincial government invest non-renewable resource royalties above the $4.75-billion mark in other areas. And the form that these investments take poses an unprecedented challenge to Canada.

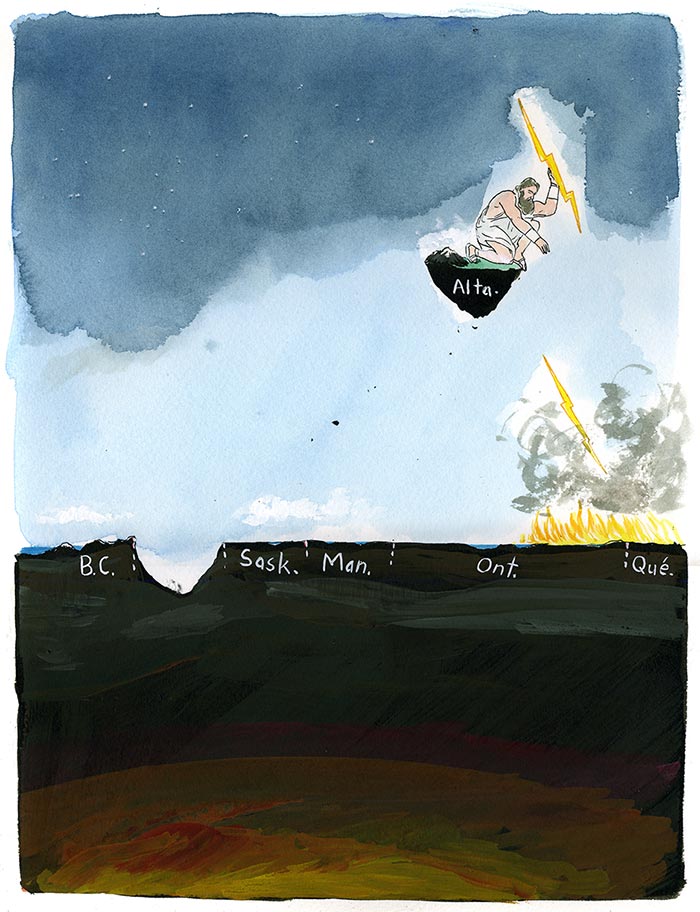

Never before has one region had no financial reason to remain part of the country, but Alberta will soon be at that point. Central and eastern Canadians might see the province as the new bully on the block whose time will come, but the truth is that hope resides in Alberta’s largesse. The über-province could decide to include the rest of Canada in its spending and investment plans. But if it decides to simply play up its own advantage by, for instance, dedicating itself to curing cancer, stowing money away in special research funds for knowledge-based industries, or investing offshore, there may be little the rest of us can do about it.

Prime Minister Harper has promised to deal effectively and fairly with the “fiscal imbalance” between Ottawa and the provinces, but he brings some baggage to this issue. Harper was one of the co-authors of the infamous 2001 “firewall letter,” a clear statement that Ottawa had little business in Alberta’s affairs. But with Ontario Premier Dalton McGuinty describing Alberta’s wealth as “the elephant in the room,” a showdown is brewing over how to deal with the province’s burgeoning riches.

Enshrined in the Constitution Act of 1982, the federal equalization program is designed to ensure that “have-not” provinces can offer comparable levels of services as “have” provinces. Then—Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau cast it as a vision of a sharing and compassionate nation, but official equalization came fast on the heels of the nep, in Alberta the bête noire of federal interference. The nep was enacted when world oil prices were peaking as a result of the 1979 energy crisis. A tax on energy exports had already been imposed but, fearing that rising oil prices would enrich Alberta and cripple Ontario’s manufacturing base, Ottawa crafted legislation in 1980 that shifted exploration out of Alberta’s control and into federally administered territories. Albertans were furious, and it seemed no amount of federal transfers could mitigate the damage done.

Flashing forward, in June 2006 a panel appointed by the federal Liberals released its report on equalization. “Equalization reflects a distinctly Canadian commitment to fairness. It has been described as the glue that holds our federation together,” the report says. The chair of the panel, Al O’Brien, concluded that for equalization to be effective, natural-resource revenue must be included. Alarm bells went off in Alberta. With McGuinty gaining support for reforming the equalization program, wary Albertans want barriers erected and are looking for homegrown alternatives to a potential federal cash grab.

As it stands, Alberta and its resource revenues are not included when determining the average provincial capacity for providing services. (That figure is arrived at by averaging the revenue-raising capacities of Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia.) This artificially deflates the national average, critics say, and short-changes have-not provinces of the funds needed to provide more competitive levels of service. Pushed on the matter, Premier Klein threatened to pull Alberta out of the program if natural-resource revenues were included in the fiscal-capacity calculations. (As the program is a federal initiative, Alberta cannot “pull out,” but the point was made.)

Ontario and Alberta have been the two most prominent contributors to the equalization program, but TD Bank economist Don Drummond believes that Ontario’s economy is too fragile to withstand higher equalization contributions. (Indeed, some observers envision a time when Ontario’s manufacturing base will be gutted by off-shore competition.) So if the combined forces of world demand for oil, nafta, and a diverse economy ensure Alberta’s continued growth and prosperity, they also ensure a growing dependency by the rest of Canada on Alberta.

The federal Liberals see equalization as a wedge issue for the fall and, especially if the left wing of the party prevails, they can be expected to argue that the formula should be changed to include all ten provinces and 50 percent of resource revenues (both of which the panel recommended).

Let there be little doubt that Alberta is willing to challenge the very notion of fiscal federalism. In February, when Klein proposed blending public and private health-care delivery, he knew that such a move contravened the Canada Health Act. He also knew that Ottawa’s censure and its threat to withhold $1.75 billion in health transfers meant little. Medicare supporters cheered when he backed off, but Klein simply changed tack, countering that Alberta would instead spend more money to attract even more doctors and nurses. In short, even when Alberta chooses to play by the national rules, its range of options allows it to produce levels of service that cannot be equalled anywhere else in Canada.

Equalization has always been about supporting poorer provinces, but if Harper decides to tackle the fiscal imbalance he will be faced with a new phenomenon: Alberta’s wealth could turn the entire issue on its head, as the nation grapples with what to do with the richest province.

Inside Alberta a pitched battle looms between “little Albertans,” who wish to retreat from the nation and husband their wealth, and “pan-Albertans,” who seek to supplant Ontario as the heartland of Canada and move the province into a leadership role in national affairs. “The real issue is whether Alberta is going to look inward or outward,” says Peter Lougheed.

The internal debate revolves around three radically different options: lower or eliminate taxes, be they personal, business, or property; increase spending on social services and infrastructure; or save and invest a significant portion of revenues for future use. The first option, embraced by a somewhat unholy alliance between big business and the poor, would make Alberta a virtual tax haven, or, as the Canada West Foundation’s Roger Gibbins puts it, “the Cayman Islands of Canada.” This approach has the intrinsic appeal of being simple, but a further lowering of taxes in the least-taxed region of the country will create a competitive advantage that could destroy the rest of Canada. As Gibbins has warned, “Alberta’s capacity to alter the competitive balance of the country is far greater than Canada’s ability to absorb it.”

According to province-wide polls, increasing program spending is the preferred option for most Albertans. But critics insist that when energy royalties slow down, high spending commitments will lead to deficits. They further argue that such generosity will lead to social services and infrastructure improvements that are so superior to those offered elsewhere that the population influx into the province will be impossible to withstand. And if other regions empty out, this approach could ruin Canada as well.

A small minority of Albertans, including prominent oilmen like Jim Gray, wants to ensure that their province remains strong in perpetuity and believes that it should do so within the context of a strong Canada. Alberta must save but it must also invest in both the province and the country. While this strategy has yet to be fully fleshed out, the likes of Lougheed, Gibbins, Dinning, and former Reform Party leader Preston Manning seem to agree on the broad strokes. A fixed portion of resource revenues would be deposited in the Heritage Fund (Alberta’s rainy-day treasure chest) and other trusts, with the money earmarked for particular purposes. Capital would accumulate in these accounts, and the interest would be used to make investments inside and outside of the province, either independently or through joint ventures. The save-and-invest camp supports setting up special trusts similar to Norway’s Petroleum Fund, which since 1995 has collected $223.8 billion (US) in resource revenues and has current assets of just under $200 billion.

Hearkening back to his own experience with the Heritage Fund, which was created in 1976, five years into his mandate as premier, Lougheed recalls investments made in grain terminals in Prince Rupert, British Columbia, and medical-research facilities in Alberta. He believes something similar could be achieved through the Pacific Gateway Initiative, a proposed federal transportation infrastructure project intended to enhance trade with Asia, or even by locating part of Alberta’s medical-research foundation in, say, Montreal or Toronto. The Canada West Foundation suggests putting as much as 50 percent of annual resource revenues into the Heritage Fund. The investments could be targeted at health and higher education, thereby further insulating Alberta from areas of federal responsibility.

Other ideas are on the table. The right-wing Fraser Institute believes Alberta should eliminate all municipal property taxes. Indeed, with personal and corporate taxes accounting for only $8.5 billion of its $35.5 billion in annual revenues, Alberta could become a provincial-tax-free jurisdiction. Or it could simply eliminate corporate taxes—an approach under active consideration. Oil executives might be happy enough with the status quo, but as royalty payouts increase, they will be demanding new tax holidays; such a strategy would also help small- and medium-sized businesses, the part of Alberta’s corporate world experiencing tougher times.

Jim Dinning’s vision for Alberta is to replace the segregated energy industry with “a fully integrated energy system, where maximum value is extracted at each link along the value chain.” He asks Albertans to “think of the investment opportunities in the network of pipelines, transmission wires, and infrastructure linked together to pump out not only our raw natural resources but to go one step further: to manufacture finished products, plastics, fibres, resins, rubbers, and specialized fuels, and ship them around the world.” Fiscal-federalism expert Tom Courchene of Queen’s University has proposed the formation of an energy accord between British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan with the goal of developing a full range of energy initiatives.

Similar to Courchene, Preston Manning sees a “tremendous symbiosis with Quebec and its hydro resources” and would like the two provinces to “create an energy alliance that could use its leverage to put pressure on Ottawa and Washington to invest in a secure energy supply” for all of North America. Manning, the author of Think Big, talks about such steps as “part of growing up” and Alberta’s “new leadership responsibility for the rest of the country.” Says Dinning: “We’ve got Alberta to the point where we can choose to do or become pretty much whatever we want” and that now is the time for “Alberta to take the lead in Canada.” Even the normally staid and conservative Canada West Foundation states, in Seizing Today and Tomorrow: An Investment Strategy for Alberta’s Future, “As Albertans explore the transformative power of natural resource endowment, hopefully they will also seize the opportunity for national leadership.”

Inspirational language is one thing, but it will take something akin to a miracle for the Lougheed-Manning-Gibbins crowd to prevail in the tug of war over the province’s bankroll. Polling clearly reveals that the save-and-invest strategy is preferred only by certain elites. The vast majority of Albertans believe that the province’s wealth should be used to solve Alberta’s problems and that spending on health care and secondary education would be a “good” or “excellent” use of surplus revenues. The option that receives by far the least support—even less than temporarily lowering corporate taxes—is “sharing it with the rest of Canada.”

So while pan-Albertans preach big and bold ideas, little-Albertans are manning the ramparts. With a population distrustful of the long arm of the federal government, and with a history of economic highs and lows, for most the sense on the ground is get rich quick and get the goods and services while they are available. To be sure, trade delegations from Alberta visit other provinces, and at the political level there is talk between Edmonton and Ottawa, but at the grassroots a new provincialism is emerging in Alberta.

In a 2004 essay titled “Federal-Provincial Tensions: The Evolution of a Province,” Manning attempted to explain the roots of Alberta’s alienation. Albertans, he argued, came out of the Depression and World War II believing that Confederation was a “one-way street” and that “Alberta better take care of itself—especially when times are good—because in real crises, the national government cannot be counted on to do so.” This sense of estrangement manifested itself in the lament that “Toronto has everything” and that Alberta was a powerless backwater, taken for granted and invisible in national affairs. The tide began to change in the 1970s as the population and accumulated wealth grew. As premier, Lougheed tapped into Prairie pride and a can-do attitude, and slowly but surely the prevailing view became that initiative, new ideas, and success were more abundant in the West than in Canada’s traditional centres of power. Alberta now had a voice, but its right to control its own destiny was trampled by the nep and top-down federalism. As central Canada paid undue attention to Quebec or the US, Alberta was ripe for the Reform Party’s battle cry, “the West wants in.”

Today, according to Dinning, Westerners are demanding a “process that more fairly respects the region’s weight and role in the federation.” In the view of the pan-Albertans, the province’s wealth can transform Alberta and the nation as a whole. But if they are offering Canada a carrot, they are also barely concealing a stick. “If someone makes a raid on Alberta, you won’t be able to stop separatism,” Preston Manning warns. “People like myself couldn’t argue against a firewall mentality.”

Alberta’s wealth clearly poses a challenge to Canada’s future. Whether the province chooses to lower or eliminate taxes, spend its way to nirvana, or amass huge holdings, Alberta’s actions will force a tectonic shift in the balance of power. Perhaps the most benign scenario is that Alberta will become Canada’s bank, making interest-bearing loans as it sees fit, and securing its own prosperity and control in the process. The issue therefore is not whether the West wants in, but whether the West will let Canada in.