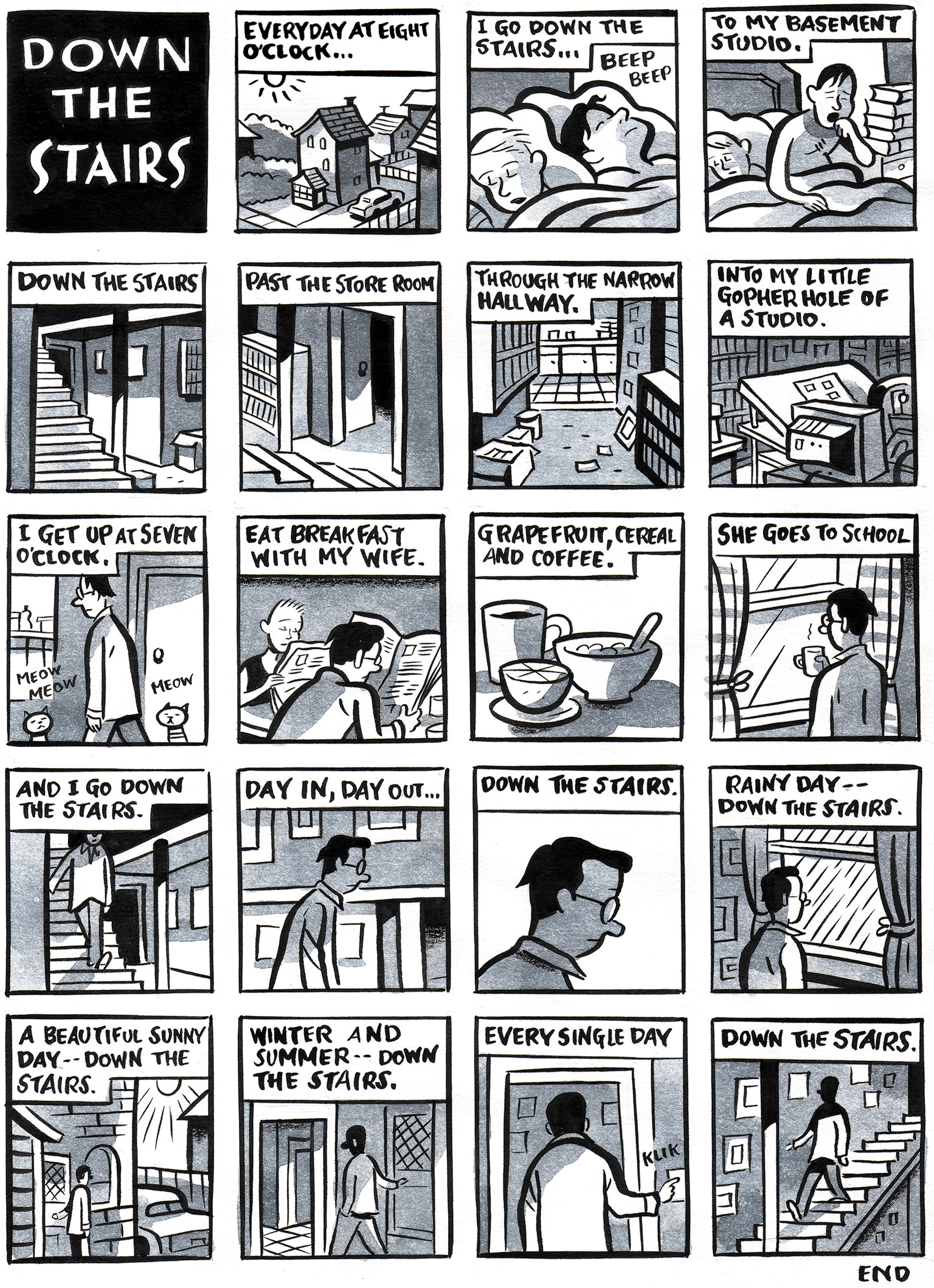

Cartooning is a solitary pursuit. The cartoonist sits alone at a drawing table for most of his life, struggling with himself and his past in an attempt to create something meaningful. It’s the nature of the work. I always tell aspiring artists that if they want to be cartoonists, they’d better enjoy being by themselves.

A cartoonist isn’t like a writer. Writing requires a special kind of focus. Your mind must be utterly devoted to the task at hand. When I’m breaking down a strip or hammering out dialogue, I’m using that writer’s focus. But drawing and inking are different. They use different parts of the brain. I often find that when I’m drawing, only half my mind is on the work—watching proportions, balancing compositions, eliminating unnecessary details.

The other half is free to wander. Usually, it’s off in a reverie, visiting the past, picking over old hurts, or recalling that sense of being somewhere specific—at a lake during childhood, or in a nightclub years ago. These reveries are extremely important to the work, and they often find their way into whatever strip I’m working on at the time. Sometimes I wander off so far I surprise myself and laugh out loud. Once or twice, I’ve become so sad that I actually broke down and cried right there at the drawing table. So I tell those young artists that if they want to be cartoonists, the most important relationship they are going to have in their lives is with themselves.

There is something very lovely about the stillness of a comic book page. That austere stacked grid of boxes. The little people trapped in time. Its frozen and silent nature acting almost as a counterpoint to the raucous vulgarity of the modern aesthetic. Of course, the drawings aren’t really frozen. When we look at them, we immediately invest them with life. That little ink world pops into life as our eyes move across the drawings. I actually find it very difficult to look at a cartoon and hold on to the stillness. The essence of the cartoon language carries a kind of animation with it. This is true even with a single drawing, but it is especially evident when one panel is placed next to another. That juxtaposition creates a tension that implies motion and time. This illusion is one of the medium’s primary charms.

Comics have such a simple little bag of tricks. Some tiny drawings in boxes, a few words contained in a bubble, a handful of rough-hewn symbols. Almost nothing to it. But the closer you look, the more you come to appreciate their almost endless possibilities.

And those drawings aren’t really silent either. There is implied noise within them. It’s hard to put your finger on why that noise is there, but it is. Just recently, I was drawing a comic book page that demanded a perfectly silent scene. Just leaving out the sound effects or word balloons didn’t do it. Even drawings of a character sitting alone in a darkened room did not imply total quiet. In the end, I was forced to letter in, at the top of the panels, the words “utter silence.”