Spoken Truths

Listening to history

Alex Westgate

In 1991, when Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs performed oral histories to defend their territorial titles in the Supreme Court of British Columbia, the chief justice ruled that their words failed to serve as reliable evidence of history or land use. Canada’s legal system has privileged the written word as the authority for truth, while Aboriginal cultures rely on stories recounted from generation to generation, their fluidity an acknowledgement that objective truth is unattainable, and that the understanding of history is grounded in a time and place. A narrative’s integrity is reinforced by its collective making; elders and other listeners shape and qualify stories for accuracy as they are told. It took six years to bring Delgamuukw v. British Columbia to the Supreme Court of Canada, and in 1997 Chief Justice Antonio Lamer declared that Canadian courts must treat written and oral traditions “on an equal footing.” Although oral histories are now heard, giving them full legal authority will take more than just listening.

—Sarah Boivin

On a June night, in the front row of the balcony at Vancouver’s Vogue Theatre, a guy in an orange T-shirt sits curled into himself like an ampersand. He’s not much past twenty and looks well over six feet tall, high-tops tied tightly around his battleship feet. He must have towered over everyone else in the hallways of his high school, a prime target for the cruel jabs that can knock a kid down with a single gust of unwanted attention.

He is crying—the slow, silent seepage of a deep wound. Meanwhile, onstage, spoken word poet Shane Koyczan weaves his way through “To This Day,” his poem about bullying and the damage it can wreak: “I’m not the only kid / who grew up this way / surrounded by people who used to say / that rhyme about sticks and stones / as if broken bones / hurt more than the names we got called / and we got called them all.”

In between poems, a girl shouts, “I love you!” like this is a Jonas Brothers concert. Koyczan is a far cry from a Jonas; he is heavy and bespectacled, with a beard that starts at the edge of his jaw and crawls down his neck. “Did they tell you this is a poetry show? ” he asks the crowd, and they laugh and cheer and whistle.

Poetry doesn’t generally fill theatres. Early this year, though, Koyczan collaborated with Giant Ant Media, a Vancouver creative agency, to set his poem to music and illustrate it with crowd-sourced animation. The subject matter was already lodged in the public consciousness; Koyczan dressed it up in the nostalgia of childhood cartoons, and uploaded the video to YouTube, where it blew up. As of this writing, it has more than 10 million views. It earned him an invitation to speak at the TED Conference in Long Beach, California, and he is at work on the libretto for an anti-bullying opera, which will premiere at the Vancouver Playhouse next fall.

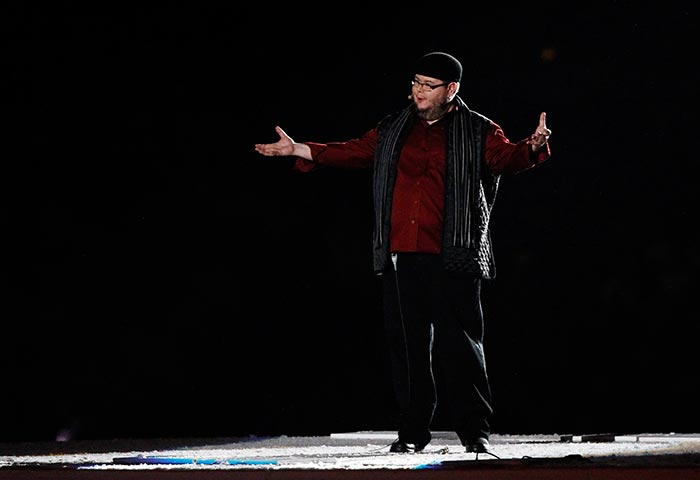

Despite his recent fame, he is no overnight sensation; he has been working for more than a decade. Many people first encountered him in 2010 when he presented his ode to Canadianness, “We Are More,” at the opening ceremony of Vancouver’s Winter Olympics. The art of spoken word is complicated: a writer is both performer and scribe, and must consider delivery and cadence as well as the words themselves. During his performance at the Vogue, his voice crescendoes from near-whispers to thunderous shouts, swelling alongside a simple soundtrack of strings, keys, and a backup singer’s voice provided by his band, the Short Story Long.

“Spoken word comes back in cycles,” he tells me a few days before the show. “You think about the beginning of civilization. All there was was spoken word. They hadn’t invented writing yet. So that was art. It was storytelling. It was poetry, and I think the world is coming back to that now.”

He started writing and performing when he was eighteen, after an album by indie folksinger Ani DiFranco turned him on to the prospect of moving people with words. “I heard this person talking directly to me, and not only that: based on her voice, just the way she was saying it, the way she was singing it, I believed her. It was so powerful. I was like, that’s what I want to do,” he says.

He grew up in Yellowknife, and Penticton, in BC’s Interior, where he was raised by his grandparents and still lives. He was bullied as a kid, partly because of his unconventional family situation, but mostly just because—experiences that inspired “To This Day.”

His willingness to render these personal tragedies into art generates visceral reactions, not just the sobs and cheers he receives at live events, but also the shares, likes, and upvotes he gets online. Kindred spirits have sent messages of gratitude, while others have posted reaction clips of themselves watching the video in tears. In those comments, as well as the Reddit threads and the Twitter chatter, one comparison keeps cropping up. A guy behind me at the Vogue says it out loud: “He sounds like Macklemore.”

Rapper Macklemore, half of the Seattle duo Macklemore and Ryan Lewis, was propelled into the spotlight following the release of “Same Love,” a pro–gay marriage anthem produced during Washington State’s successful 2012 campaign to legalize same-sex marriage, and it also went viral. While hip hop and spoken word share qualities of lyricism and flow, Koyczan laughs when I mention the comparison, as if he has heard it before. “People are starved for not only lyrical content but honest content that moves them, or says something about the world we live in,” he says.

But Macklemore and Ryan Lewis are on the radio, topping out the Billboard charts with lighter fare such as their hit “Thrift Shop,” and making quick work of the music award and festival circuits. Despite his success with “To This Day,” Koyczan knows that spoken word is not about to take over the mainstream.

“People find something that connects them to other people of like mind,” he says. “Spoken word is just one of those things. I wasn’t trying to get it to a place where I was going to reach 10 million people. I’m glad it has gotten there, but it really was just for those three people in school who are going through bullying.”

This appeared in the November 2013 issue.