Everybody had a target on his back. His or her back. Lists up all over the building so you had to look and see who’d bump you. Or whom you were going to bump. The bumps were blocked, and everybody was told there would be tribunals to appeal the blocks. If a block held, you had to do another bump. Some people had up to twenty-five people trying to bump them.

Everybody agreed you had to wait and see.

Everybody reconfigured his resumé so it was bump-proof. His or her resumé.

Some people were escorted out of the building while they were broadcasting the budget. Others were given twenty minutes to clear out their desks.

They said if you hadn’t heard anything by the end of the week, you wouldn’t hear anything.

But the following Monday, more people were called in, one at a time, and let go.

People walked into new positions they barely knew how to fill. People didn’t have the skill sets, basically. The new people came in, from the jobs they had lost in other departments (jobs they knew how to do), and the people clearing out their desks just looked at them. Gave them the worst kind of look. Let them know they were very pissed off at losing the other person, the person who had been bumped.

People made a shovel of their arm and swept it along the desk so everything, cups with pens and paper clips and some kind of sticky, grit-caked resin at the bottom, a snow globe from Whistler, a pewter-framed photograph in one instance, lined on the back with dark blue velveteen beginning to peel away from a splotched cardboard backing (juice from the packet of pickled ginger that came with the sushi from the food court in the mall), and on the front, under cracked glass, a photograph of a baby girl—everything fell into the cardboard boxes held flush to the edges of the desks.

Everybody said everybody was afraid to open his mouth. His or her mouth. Everybody literally whispered. If they were all sitting together in the cafeteria, they’d cast their eyes left and right before speaking and hunch in to talk.

They even looked over their shoulders before they spoke. They sometimes did this in an exaggerated way. They overdid it. They joked about the clandestine nature, and then they drew back and said it wasn’t funny.

They were tainted, basically, is what it felt like. They felt diminished by everybody else in the cafeteria who had not been bumped or cut or axed.

A lot of people were angry like you wouldn’t believe. They had great stores of anger. It must have been there all along, tamped down.

People said certain people had no balls or they were pussies, or they asked each other why wouldn’t anybody take a stand. One guy took a stand, and he was disciplined and had to take a package.

Or else it came out of nowhere, the anger, fully formed. Burst out of their foreheads like firehoses, or demons holding blowtorches.

There were rumours that if someone stood up redundancies would be rescinded, but nobody would stand up.

People couldn’t believe how cowardly some people were.

Their co-workers.

Stand the fuck up, somebody, that’s what people were thinking, but they wouldn’t stand up themselves.

The Downeys were both let go on April 2. Marilyn Downey was called into Chad’s office, Chad her senior manager, at 11:30 a.m.

Marilyn, who was in clerical at Innovation, Business, and Rural Development for seven years, and her husband Noel Downey, who was in tech support with the office of the chief information officer, also seven years, and who was let go at the end of the same day, around 4:30 p.m. OCIO lost two people. Now if you work in the building and you need a new keyboard, forget it.

The Downeys had married in Cuba six months before, and Marilyn wore a mermaid-style ruched silk dress, so tight all the way down to her ankles she couldn’t even really go to the bathroom. She almost drowned in an undertow during the wreck-the-dress photo shoot, the bridesmaids on the beach with their iPhones at arm’s length, the foamy surf at sunset, and Marilyn trying pretty hard not to actually wreck the dress, and nobody helped her out of there until they had some really good shots, half of which were instagrammed while she was going down for the third time.

The Downeys had recently bought a new three-bedroom with two and a half baths and a two-car garage in Prince William Estates. Prince or King or some other ass-kissing name, with a mortgage Noel’s parents had co-signed. The down payment, even though they were first-time homeowners, took everything they had.

Then they had the stink from the dump to contend with, now that it was warming up, and the property devalued before they stepped over the threshold. Soon a new Re/Max sign swung on a faux wrought iron pole, with a neon sticker over it announcing New Price.

The Downeys, for example, were very angry.

Fiona Jamieson knew Marilyn Downey from her book club (last book The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, rating 9.5), and then the sex toy party, for which many of them had got primed on martinis at Fiona’s beforehand, and Marilyn had modelled the edible underwear (banana, bubble gum, watermelon, hot pepper).

Fiona had just purchased a new stackable washer-dryer set, but she had to return it. She had been teaching adult basic education at the College of the North Atlantic. Private business colleges were taking over ABE now, for which the students would require loans in the maybe tens of thousands, for upgrading, like in the ’80s when they were getting student loans to learn WordPerfect 2.2 at the Veronica Vokey School of Business.

The movers had nicked the paint off the door frame leading to Fiona’s basement. More than the paint, actually, there was a splintering noise after a sharp crack that seemed to her a synesthetic rendering of the pain experienced by the loss of her job. A chunk of the door frame had been gouged off and was left hanging by sinuous blond threads of wood.

Fiona had taught people with severe disabilities, emotional disorders, and economic disadvantages. She’d had two home-schooled evangelical Christian teenagers who could not cope with their flaxseed-eating, woven-shawl-wearing, ukulele-picking, depressive/ecstatic, rapturous/repressed pious mothers anymore, and had taken to cutting themselves (just scratches) or playing online poker.

There was a young girl whom Fiona had no record of, whose name did not appear on the enrolment sheet she took attendance from, but who showed up late and sat in the back. Fiona thought the girl was probably of very low intelligence and perhaps developmentally challenged and non-verbal. She was probably coming to class just to get in out of the cold.

The girl emanated a pelt-thick body odour, and had a pale complexion and eyes so deep set they appeared in shadow under the buzzing fluorescent lights of the classroom. She had long, very dark, oily hair that had once been bleached, so the bottom half was a tawny yellow. The mass of hair fanned out over the shoulders of a man’s oversized Gore-Tex windbreaker the girl wore every day and did not take off. It hissed softly when she turned her head and the long hanks of hair swished across it.

Sometimes she fell asleep, her head nodding down and jerking back up, a thread of saliva from her top front tooth to her bottom lip blowing out and in with each breath, her cheek eventually touching down on the desk.

Most of Fiona’s attention was taken up with Glen Reardon. One of her mature students, in his early fifties, Glen had required a great deal of endurance and fortitude to even arrive each day at CNA, because he was so beset with self-esteem issues and physical limitations.

He had not ventured out of his apartment for three years before applying online, with the aid of his home care worker, and being accepted into the ABE program at CNA, and particularly into Fiona’s English composition class, for which 40 percent of the final grade was an essay about the Challenges and Rewards of Re-entering the Workforce.

But he did. Glen did come out of his apartment for Fiona’s class. He came every day, no matter what the weather.

He wore a red crash helmet and knee pads, and moved with a jerky wrenching-up of one rubber-tipped titanium crutch and then a thrust of forehead and face guard and licorice-twist limb, a jolt/stagger that allowed him to be suspended for the brief instant it took to slam the crutch back down. He’d lean hard on it before dragging the other one up and slamming it down, too, a foot and a half ahead of the first one.

Once he had crossed the classroom, he could aim himself into the child-sized orange moulded plastic chair bolted to a metal bar of other chairs, at the end of the first row.

Each chair was fitted with a desktop, gouged with obscenities and hearts in Bic pen, that folded away on hinges. Glen would collapse into the chair and flip up the desktop and let the crutches drop to the floor. He would take out a spiral-bound notebook and a pen, which the tremor in his hands would not allow him to make use of but which he brought every day.

He was a slack-faced, sometimes drooling, fierce-eyed man whose speech was garbled and drenched with saliva, but as the months wore on Fiona had learned to decipher his sense of humour, elegant and honest. He was subject to frequent, randomly triggered rages, instant and of maximum intensity, but Fiona found them inspiring. His fidelity to English composition touched her.

The other students caught on, too, began to untangle what he said, and even the Christian kids with the studded leather wristbands, dog collars, acne, shaved heads, plaid underwear, and chained wallets in the back pockets of their jeans with the low-hanging crotches, even they bought him Cokes with their own money, from the machine down the hall.

The Challenges and Rewards of Re-entering the Workforce essay that Fiona had transcribed for Glen, word by agonizing word, talked about the water stain on the polystyrene ceiling tiles in his mouldy basement apartment, and the particular pine-scented industrial floor cleaner the landlord’s cleaning lady used, a mix of sinus-slicing chemicals that brought on his chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He could not make himself understood to the cleaning lady to stop her from using the cleaner.

There had been a few attempts, mentioned in the essay, when Glen saw the cleaning lady coming with her buckets, and he had worked himself into a violent fit of shaking and shouting, stabbing the air in the direction of the cleaning products with the tip of his crutch, but she had shouted right back, even louder than he, that it was no trouble, that it was the least she could do, that she was grateful for the opportunity to help.

Also mentioned in the essay (inverted pyramid format), the rate of deterioration of his condition (very fast), and the kindness of the nurses in the emergency ward at the Grace, when he became so short of breath he feared suffocation, and the fear that when it snowed he would never get out of the basement. If a particularly bad snowfall occurred and the COPD got bad, the snow covering each of the windows and the resulting grey light all through the apartment, like a granite tomb, and the screen door pressed closed by the weight of a drift—how akin, Glen said, all of that was to being buried alive.

And finally, the sexual longing he felt, the—never mind longing—need when the durable green, shapeless drawstring pants of polyester-cotton blend the nurses wore rubbed unselfconsciously against the chrome guardrail of his gurney while they reached up to attach a bag of saline to the IV pole as he huffed Ventolin through an oxygen mask, hissing steam like a dragon (inverted pyramid format abandoned), his climbing heart rate causing the monitor’s bleating to accelerate and, simultaneously, it seemed, to become louder and more piercing.

Glen also told Fiona to please write down that when it really felt like he was drawing his last goddamn breath, forgive his French, he sometimes felt his cock would “explode” was the word he used, the word itself exploding with spittle and sweet breath like cotton candy.

The word “explode” in this context made Fiona blush, un-teacherishly. Perhaps more hot flash than blush, accompanied by a slathering sheen of sweat so thick she felt a drip on her temple and by the side of her nose, and she was humiliated and aroused.

But never mind humiliated, because Fiona wasn’t going to see any of them again. None of them were ever likely to re-enter the workforce.

The girl in the man’s Gore-Tex jacket had not attempted the Workforce essay, but she handed in a coloured pencil drawing of a house with four windows and a front door and a tree on the side and smoke coming out the chimney.

There was a scroll drawn over the house that said Home Sweet Home, and Fiona was certain there was no satire in the caption, though they’d already covered the Learn and Laugh with Satire and Technology unit. One of the learning outcomes was the production of a concept map on satire in a) A Modest Proposal, b) Lord of the Flies, c) Shrek, or d) The Simpsons.

The girl had looked Fiona in the eye just twice during the academic year.

Both times, the look was a connection characterized by a particular intensity that can only be achieved through accident, magnetic and mesmeric, alive with telepathic current.

The first time, the girl was reaching her hand into the 40 Timbits Snack Pack Fiona had brought for the class to celebrate the completion of unit five (Exposition, Setting, Atmosphere and, inexplicably, Concrete Poetry), and the girl had glanced up, half-cringing, as though expecting a slap. She had taken a handful, like, five Timbits in the one go, and Fiona saw in her eyes that she was very hungry and knew intuitively that the girl was pregnant.

The second occasion when their eyes met was while the girl was handing Fiona the loose-leaf with the drawing of the house with the scroll that said Home Sweet Home, in lieu, it seemed, of her concept map.

The look in the girl’s eyes this time was greedy, child-innocent, and aggressive, but at the same time closed down, shut off, and dead. Basically, a look Fiona wasn’t likely to forget in a big hurry.

You don’t have seniority, Joanne Brophy’s supervisor was saying. It had nothing to do with the quality of Joanne’s work, which, her supervisor was saying, was exemplary.

She was calling to say Joanne should bring in a cardboard box to clear out her desk. She was saying everybody in the office was demoralized by the bump. They were all really upset by having to see her go.

Joanne had been at the supermarket holding a bunch of beets by the stems. Clots of black soil hung on to the hairy roots at the bottom of the dark bulbs, a dank mineral loam, ozonish, purple smelling, the waxy skins slightly damp.

Joanne’s husband, a sheriff at the provincial court, had been laid off the week before (now they didn’t have enough people to operate the metal detector, so come on down, everybody, to provincial court, with your guns and switchblades), and she, Joanne, had dropped her cell into the perforated stainless steel shelving unit that showcased the produce.

The phone got slimy in the fresh cilantro, and the automatic sprayers let out a blast of cold mist over which she could still hear the static-riven, plaintive voice of her supervisor explaining the tribunal process.

Joanne had a young client who had given the shelter’s number to a girl who was fourteen and pregnant and on the street, but who was not a client. The girl who was not a client would phone while Joanne was working intake on the night shift for Better Decisions, Better Lives.

The girl who was not a client, and therefore could not be serviced through BDBL, was advised by Joanne, many times, to call social services, and, as Joanne had said repeatedly, she would very gladly provide the number.

If the girl were to become a ward of the state, the baby would also become a ward, obviously, which means, yes, the girl would more or less have to give up the baby, and the baby would probably go into the privately managed First Steps program, which was housed in the apartments on Kenmount Road, and would be taken care of by staff who rotated on twelve-hour shifts for the rest of the child’s life, but on the upside they could both get all kinds of services not available to the girl now. Joanne advised this course of action until she was blue in the face.

Even though Joanne had informed the girl that she couldn’t help her under the present circumstances, the girl would call up anyway, and talk for hours about how afraid she was of the baby coming out. She said she had no idea how that could happen. She said she didn’t believe it. Where your pee comes out?

When Joanne tried to get off the phone, the girl who was not a client, and on whom there was no paperwork, and who wouldn’t even give Joanne her name, and who may or may not have left a foster home and wasn’t going back there no matter what, the girl would pretend to go into labour. She’d tell Joanne she thought the baby was coming and could she, Joanne, just stay on the phone for, say, another twenty minutes, until the pains went away?

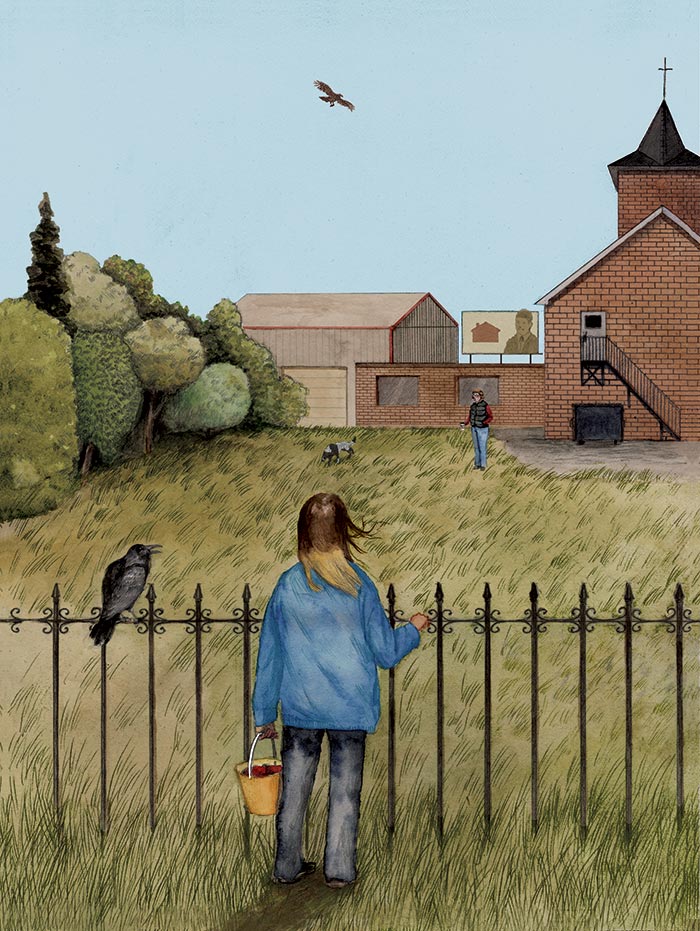

Once, when Joanne told the girl she really had to hang up, the girl had said, I’ve seen you with your dog. You got a white dog with black spots, don’t you?

Joanne had a mutt named Twist, rescued from the SPCA, whom she walked every morning up in the churchyard behind the dance school after she got off work at the shelter.

I seen you with the dog, the girl said. Up by the church there in the morning after work. Sometimes you bring your coffee. I seen you there.

Joanne let the dog go in the field behind the churchyard at 6 a.m. every workday, after she arrived home, and before she went to bed for the morning until mid-afternoon. There was never anybody around, not even traffic, at that hour.

The leaves were already out in the field behind the dance school, and in places the foliage and weeds were very high and overgrown. The sun came through greenish and smelling green. Joanne’s jeans would get soaked with dew up to the knees.

Sometimes she brought her coffee with her, and the dog would make it splash all over the cuff of her jean jacket, until they got to the churchyard and she let him off the leash.

Joanne didn’t see how the girl could know about these moments when it was just beginning to get light, everybody asleep and just the rustle of the dog in the alders.

She felt around in the leaves of misted cilantro for her phone and realized she’d been fired on the girl’s due date. The smell of wet cilantro remained on her fingers all day.

If Elizabeth O’Brien had to rely on something about herself, this was the thing she could definitely tick the box for: composure.

People loved to see Elizabeth coming. At a party or in the field, she was full of puns and innocent flirtation, a jollier of introverts, a beautiful woman, glowing from hours spent in the wild. If someone offended her, by no means an easy thing to do, she became serene. Sometimes as it sunk in, the offence, she even smiled involuntarily. Her teeth were very white, but naturally so. She hadn’t had them whitened. She might have had to lower her sunglasses from her hair, if the offence had been particularly disturbing. But she always managed to maintain a placid composure.

Environment had been hit hard, Education, Health; Justice had been hit. Justice fought back, but nobody wanted to hear about Environment.

She had lost her job managing the biggest colony of Leach’s storm petrels in the world. At night, lying awake in bed, she sometimes imagined she could smell the bird colony’s pungent odour. The birds nested underground, and the odour, carried on the sea breeze, could be as sharp as sheep shit, a mingling of sun-warmed peat, or orange spruce needles, or semen, berries, rotten fish, ammonia.

By “managing,” what she meant was, she went out to an island three kilometres from shore, to stay for a week to ten days with a couple of biology students, and they tagged the birds and collected data.

Once, the helicopter that had delivered them was lifting off, and Elizabeth had discovered that the feds had boarded up the well, the only source of drinking water on the island. She waved her arms into the caterwauling stir of wind and roar, and the helicopter touched back down, one ski pirouetting in the racing grass. She ran, bent over, under the blades and screamed to the pilot did he have a square-head screwdriver, and he tossed it to her before the helicopter floated up and away.

The first thing was, she lost her composure. But she experienced that in private. The loss of her job was a judgment, and she was surprised by how personal it felt.

Elizabeth got a short-term contract almost immediately with a Japanese film crew who wanted an eagle’s nest they could shoot from above. She could have shown them any number of eagles’ nests from the water, but they wanted to look down.

She had heard there was a nest somewhere between the marine lab in Logy Bay and the Robin Hood dump. She went with Joanne Brophy, her sister-in-law, and they walked for an hour and a half, and Elizabeth stopped and said, Did you hear that? Did you hear something that sounded like a drop of water falling on a stone?

Joanne said she had heard it.

But it’s not raining.

That’s a raven, Elizabeth said. They can imitate any sound. That’s a raven imitating a drop of water falling on a stone.

The closer they got to the dump, the more faded plastic grocery bags there were, hanging tattered in the trees. Elizabeth told Joanne that during the winter there would be lines in the snow, just like the tracks of cross-country skis, and at dusk they would fill with what looked like black liquid, something shiny, molten, coursing through the snow, and those were the rats, she said.

Hundreds of thousands of rats. And the rats were starting to be a problem for the city. They were showing up all over. A neighbour had seen one in her garden. There was a squashed rat on the cul-de-sac at the end of Elizabeth’s street.

Then they saw the eagle through the trees. The eagle was over the water, way above, slow moving, or not moving at all, wingspan maybe five feet, Elizabeth said. Something writhing in its claws.

But when she and Joanne broke through the brush to the edge of the cliff and looked down the coast of vertiginous granite, all they saw were giant splashes of guano. Elizabeth looked for a long time through the binoculars and then reached into her knapsack and took out a bag of trail mix. She opened the Ziploc seal, and Joanne held out her hand.

Where the hell is the nest? Elizabeth asked.

The girl came into St. Clare’s emerg at 1:27 a.m. on the last week of the cuts (mostly admin), and Mike Andrews, who had been a triage nurse for two years, did a brief assessment, took her vitals, asked about her chief complaint (abdominal pain, shortness of breath), and ascertained that the girl was fourteen years old and in the early stages of labour.

He left a gown for her to change into and said he was going to have the hospital social worker come in and have a chat with her. He told her not to worry about anything, she was going to be well taken care of. He asked her would she like a Popsicle.

We have two kinds, he said, orange and orange. That’s all that’s left out there.

The girl said she’d have an orange one.

He slid the curtain around her bed so she could change.

I don’t want no social worker, the girl said. Her shadow bobbed and ducked and weaved on the folds of the curtain.

Oh, you have to see the worker, Mike said.

The next morning, in the churchyard behind the dance school, the dog wouldn’t come. Joanne called the dog. But the dog wouldn’t come. The tips of the slender alder branches flicking back and forth, a moving patch of thrashing leaves, flinging droplets of last night’s rain.

The dog was not a barker. Joanne had never heard him bark, but he could make a high-pitched whine in the back of his throat that sounded half-human, a trilling-up of yelps.

Once, several mornings ago, he had broken out of the trees with something in his mouth, and he had been making that noise. It turned out to be a dead crow, the maggots white and wiggling in clots over the black feathers.

Now he was making the noise again, his wagging hindquarters swallowed in a tight, wet tunnel of shiny leaves. Joanne pushed through the branches, her skin goosebumped because of the stink.

The stink assaulted her and kept assaulting. It had a supernatural edge, ancient and sacrificial, and she felt it hammering in her skull. The dog’s elongated yelp and the feral choking sound of him tearing something apart. Then she broke into the little clearing and saw the fierce yellow of the overturned beef bucket.

The dog was sniffing what looked like a blackened, glistening slab of burnt wood, but it was salt beef. When the dog’s nose touched it, the shiny black coating of flies, sparking emerald and sapphire glint, lifted and buzzed like a chainsaw. Bloody chunks of purplish meat lay all over the ground. There were strings of yellowed fat on the grass, and she was gagging from the smell that rose with the flies in visible waves of sun-crimped air. Joanne kicked the dog away.

Get out of it, she said. Hey, get out.

A membrane of scum or whatever it was had draped itself over the dog’s snout, stretching over his black nose like a burst chewing gum bubble, and the flies were beading his mouth and eyes, and he snapped at them and galloped to her, frenzied with the blood and the buzzing. He dug his forehead into her thigh, wiping off the flies and grazing her hand with his teeth.

She snatched her hand away, and he jumped up and planted his paws on her chest, panting in her face, so close she could smell the raw mineral rot on his breath. And she knocked him down.

Put it down, she said to the dog. Give it to me. Here.

But the dog no longer had anything. He trotted past her and back out to the churchyard. Joanne rubbed her sneaker against the long grass, back and forth, vicious scuffs, trying to get the sole of it clean.

Five weeks after the cuts, people were saying some positions were being rescinded. Many positions. People were beginning to hear this one or that one got his job back. His or her job. If you could make a good case, they might give you your job back. People wanted to know why they hadn’t just left everything alone in the first place.

Marilyn Downey received a call two weeks after being let go, a few days after the sale was finalized on her home in King William Estates. Basically, it was Chad, her former manager, calling with an employment proposal. It was the same job she had before, but she would be rehired a few steps down the pay scale, and there would be an increase in responsibilities.