the honourable rob merrifield

Minister of State

Transport

Dear the Honourable Rob Merrifield:

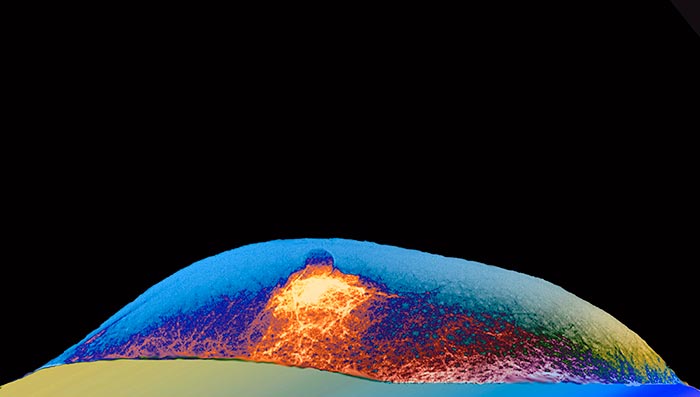

I’ve never written to a politician before. Today, however, I discovered some particularly irksome news, and I’m holding you responsible. Apparently, under your oversight as Minister of State for Transport, Canadian airports will soon be outfitted with body scanners. Through some sort of digital black magic, these machines will create a three-dimensional image of a fully clothed air traveller’s naked body, and display this image on a computer screen for security personnel to peruse, wonder at, judge, and (one would only assume) ridicule.

A person’s naked body, sir, is a private thing! How ogling even suspected terrorists’ bits and pieces somehow makes our country more secure is baffling enough—but what confuses me most of all is that public dissent on this issue has focused on human rights, whatever those might be. My concerns are a bit more… well, corporeal.

The Mile-High Club

How the golden age of air travel was hijacked

It’s the height of the Swingin’ Sixties. You smooth out your suit, climb the steps, and greet your lovely hostess, who welcomes you with a dry martini: “Would you like that with an olive or a twist?” Then the flight takes off. In air travel’s heyday, when fares were standardized, airlines won passengers by offering greater luxury than their competitors. Donald Bain—ghostwriter of the 1967 stewardesses’ “memoir” Coffee, Tea or Me?—describes passengers “served caviar, smoked salmon, Chateaubriand carved to order at seatside, and chocolate mousse while winging across the globe at 30,000 feet in an elongated aluminum cigar tube.” With the deregulation of fares and, more significantly, a surge in hijackings in the ’70s, steaks gave way to metal detectors. “[When] people realized they were going to have to submit themselves and their bags… to search,” explained Dennis O’Madigan, a former airline security director, “the early ’60s romantic approach” was dead on arrival.

Have you ever heard of something called gynecomastia, Mr. Merrifield? Known colloquially as “boy breasts,” “mannaries,” and “moobs,” this condition primarily affects adolescent males, but also returns, somewhat perversely, in men’s later years. Gynecomastia is in no way like the glorious dichogamy of the barramundi fish, which changes sex in order to spawn. A breasted man is more a blunder of anatomy akin to that same barramundi growing an udder—picture it swimming shamefully amid its peers, longing to be milked!

I am thirty-two years old. I lead a fairly healthy lifestyle: I eat well, exercise regularly, and have taken to leaving my credit card at home when I go to the bar. But this all seems in vain. The writing, sir, is on the wall—or, rather, upon my male relatives’ chests.

You see, in their mid-thirties most Malla males tend to develop. I have one elderly uncle, a solid B cup, who parades around topless, like some brazen exotic dancer anxious for a turn onstage. And while there exists undeniable camaraderie between him and other gynecomastics in my family, I do not wish to become bosom buddies with anyone. I don’t want moobs, sir; they are unsightly and gross.

Sadly, if the bodies of my grandfather, uncles, older cousins, and my own father, bless him, are any indication, I am cursed to join their chesty fraternity. It’s a horrifying prospect, and I trust you can imagine the anxiety, Mr. Merrifield, with which I wake each morning. I often find myself standing in profile before the mirror, gazing with trepidation at my chest for those first telltale lumps. Simply put, I am living the life of a particularly anxious eleven-year-old girl.

And so, in a way, I speak not just for myself here, but in solidarity with these pubescent young women, when I demand that you reconsider installing body scanners in Canadian airports. Think of people like me, and perhaps a granddaughter you may or may not have. These are private times; we do not want the first signs of our blossoming womanhood, as it were, to be announced through digital imagery; nor do we wish to share this intensely personal discovery with a complete stranger—let alone an entire taser-wielding squadron of them.

This isn’t even my biggest fear. There are websites dedicated to the mockery of gynecomastia, sir. What assurance can you provide that airport staff, judgement impaired by the monotony of their workday, won’t broadcast our naked bodies into cyberspace? Imagine the nightmare of two hulking, giggling security guards, all tight pectoral muscles and mischief, uploading my image to marvelousmanboobs.com with an eviscerating tag line like Check out these twin towers—someone call Homeland Security!

Mr. Merrifield, the human body is a temple. A weird temple, mind you, with an outright defiance of architectural logic, and great tufts of hair sprouting from unlikely places—yet it is something holy, and wholly private, and should always be regarded as such, even if Osama bin Laden is still roaming the hills of Afghanistan, or wherever he is. (Good luck with that, by the way.)

Lastly, if it is indeed with “honourable” intentions that you insist on installing these devices, then be a man of honour, Rob. In the image gallery of your own website (merrifieldmp.com), the most intimate photo of you, golf-shirted and nipple deep in a field of canola, reveals only forearms and a shadowy glimpse of neck. If you expect the same of the rest of us, let’s see what you’ve got under there. Take off your shirt, sir. Canada deserves a look.

But things need not degenerate into such petty tit-for-tat. All I ask is that you hear my voice. It is the voice of one man—in spirit, in mind, and, for now, in body as well. But who knows how long that will last?

Yours in trust,

Pasha Malla

This appeared in the June 2010 issue.