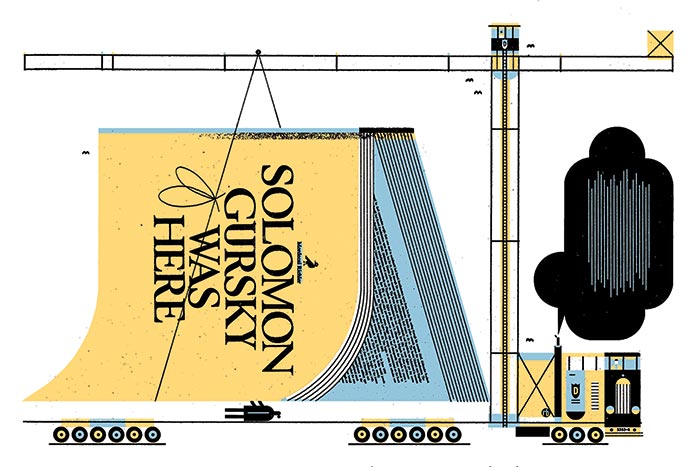

Books discussed in this essay

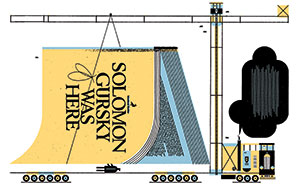

Solomon Gursky Was Here

by Mordecai Richler

Viking Canada (1989)

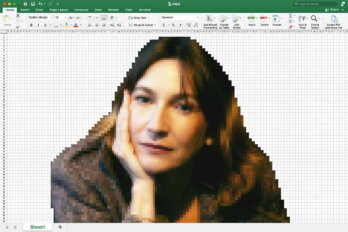

Possession

by A.S. Byatt

Chatto & Windus (1990)

Blackstrap Hawco

by Kenneth J. Harvey

Random House Canada (2008)

The Man Game

by Lee Henderson

Viking Canada (2008)

River City

by John Farrow

HarperCollins Canada (2011)

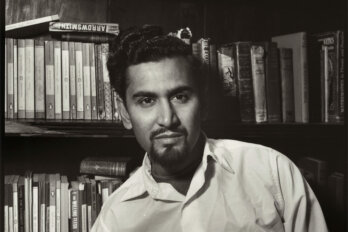

By midway through the 1990 Booker Prize dinner in London, Mordecai Richler knew that his novel Solomon Gursky Was Here, one of six titles shortlisted for the award that year, was not going to win. Neither the fifty-nine-year-old Montrealer, typically rumpled even in a tuxedo, nor his elegant wife, Florence, had failed to notice where the TV cameras were already aimed: at the nearby table of A.S. Byatt, in the running for Possession. Byatt duly mounted the podium to collect the prize.

Possession, an erudite literary whodunit, proved a popular choice, climbing the bestseller lists and eventually becoming a film starring Gwyneth Paltrow. The career of the fifty-four-year-old Byatt, who by then had ten novels and critical works to her credit, was changed by the Booker. Less measurable was what impact, if any, her book had on how fiction was written, and read, in the UK. Even a novel as original as Possession fit snugly into a tradition that arced back to nineteenth-century titans the size of Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins. Byatt, in fact, used such sturdy Victorian fictions as models.

But had Solomon Gursky Was Here been chosen by the jury, more than Mordecai Richler’s career might have been altered. (His one previous Booker nomination, for 1971’s St. Urbain’s Horseman, predated the prize’s enormous impact on authors’ sales and reputations.) The elaborate, stylistically audacious novel had no obvious antecedents in Canadian literature, never mind in Richler’s own catalogue. Gursky features numerous intertwined plots spread over two centuries; settings that range from the 1840s London demimonde to the Canadian prairies during Prohibition; and a sprawling cast of characters headed up by six generations of Gurskys, the fractious Jewish clan of bootleggers turned distillery moguls.

Richler had in mind something grand with his ninth, and longest, novel—nearly 600 pages in the paperback edition. The book’s risk taking and narrative energy may even have contained a public challenge to his countrymen. Here was a distinctly Canadian novel, as vast as the nation itself, and just as singular. It was certainly not intimidated by space or history, roaming widely from the Arctic to Manitoba to Montreal, and making mischief with one of our iconic national narratives: the doomed Franklin expedition. Little is sacred and nothing is settled in Gursky, and the Canada it portrays is wild eyed and wide open—at least for those with sufficient appetite and chutzpah to finish it.

The challenge went unheeded. Though published to glowing reviews and healthy initial sales, the novel wasn’t even shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award, then the country’s only major literary prize. Within a couple of years, a quiet consensus had emerged, even among Richler admirers, that Gursky was too long and too complex, its intentions muddled. Richler himself shared an anecdote about a woman who approached him at a signing and said she hoped his next novel wouldn’t take her two years to get through, as Gursky had. “Phew,” the fan said, “what a struggle.”

The book’s fate would surely have been different had it, instead of Possession, been named at that London ceremony. As of 1990, no Canadian author had been crowned with the Booker. Michael Ondaatje, Margaret Atwood, and finally Yann Martel would go on to win the prize over the next twelve years, with Martel in particular experiencing a spike in sales and recognition at home. But more interesting than increased sales is the possibility that Canadian literature might have evolved differently had the sprawling, capacious Gursky become, in effect, a must-read. It is a major-key work of art, one of those novels Jack Kerouac described as aspiring to explain everything to everybody, published in a culture that specializes in minor-key offerings.

This is not a judgment on Canadian writing. Many of the greatest authors in the language, from Jane Austen to Graham Greene, Alice Munro to Ian McEwan, work in that minor key. Nor is page count a reliable measure of the distinction between these types of fiction. Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy is a 1,349-page novel set in a minor key; Ondaatje’s The English Patient, just 307 albeit-packed pages, resonates with major vibrations. And being proximate to the Great American Novel phenomenon—the faded but still-active quest among some American authors to capture their collective drama between the covers of a single book—may diminish Canadian impulses. Shelved between Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom and The Corrections, most novels will appear rather slight. The same holds true for books placed alongside the Chilean Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, a mammoth summation of twentieth-century degradations, set largely in Mexico.

Still, size does occasionally matter in fiction, especially if the subject is ultimately the soul of a thing. Literary visions of the souls of entities, whether a single family or an entire society, the course of a nation or a century, take their novelistic time to unfold. Martin Amis once remarked that too much of the English fiction he grew up reading amounted to little more than “250 pages of middle-class ups and downs.” A version of this, it would seem, holds sway in Canadian writing; it is hard not to remark on how many of today’s novels, whether historical or contemporary, occurring in Toronto or Tibet, come in at around the 300-page mark; 300 mostly minor-key pages appears to be our literary comfort zone. That, or it is the size of our literary soul, and anyone pressuring that frame does so at his or her own risk.

The contention, then, is that a warmer embrace for Solomon Gursky Was Here might have helped the handful of Canadian novels of similar scale and intent that have appeared since 1990, and perhaps would have bred even more. Guy Vanderhaeghe, Wayne Johnston, and Margaret Atwood, all established figures, have produced books of Richlerian heft in the intervening decades. In terms of swagger and innovation, however, younger novelists have followed most directly in his footsteps.

Two thousand eight saw the publication of both Kenneth J. Harvey’s 829-page Newfoundland exegesis, Blackstrap Hawco, and the 432-page The Man Game, by Vancouver resident Lee Henderson. (What may be the longest novel ever by a Canadian, W. Paul Anderson’s 1,376-page historical opus, Hunger’s Brides, came and went in 2005.) Spread over a century and written largely in dialect, Harvey’s impassioned argument for the singularity of the Newfoundland experience freebases voices and narrative forms. Standing in for the province itself, generations of the Hawco clan inherit the same profane temperaments and hardscrabble lives, working on seal hunts and in iron mines, manning traplines through brutal winters. Storytelling, rather than empirical truth, is paramount to their self-conception: they tell tales, therefore they are. Harvey’s mythopoetic Newfoundland is a purposeful blur of recorded history and events remembered as a kind of legend—one that, the novel suggests, is fated to remain barely comprehensible to soft-soled mainlanders. As a vision of place and history, Blackstrap Hawco is in every way fierce and unapologetic.

Less brawling in tone or scale, if no less wild at heart, is the Vancouver of Henderson’s debut. His Pacific Rim city, especially the fledgling nineteenth-

century version only lately connected by rail to the rest of the continent, is a frontier phantasmagoria, home to card-playing woodsmen and opium-addicted industrialists, indentured Chinese labourers and Snauq Indians. (One dimwit is nicely dubbed “Toronto.”) The fanciful game of the title, invented by a teenage ex-vaudevillian, crosses ballroom dance with mud wrestling, all of it done in the nude. “A waltz with a clap in the face” is an apt description of the sport that obsesses this vulgar, colourful crowd. By comparison, the contemporary Vancouver of the novel’s narrative frame seems pallid, as though the Last Spike served not to finally connect the nation but to disconnect a city from its own true nature. The rest, Henderson infers with bemusement, is cappuccino bars and overpriced real estate.

As with Blackstrap Hawco, there is a theatrical dimension to the storytelling, and the language, of the The Man Game, a performer’s delight in showing off what the novel can do in appropriately daring hands. This can make for demanding reading, especially over hundreds of pages. Though critically heralded, neither Kenneth J. Harvey nor Lee Henderson landed on the Giller or GG short lists that year.

This month, another Montrealer, Trevor Ferguson, is coming out with what may be the most recognizable child of Gursky. The 750-plus-page River City is being published under the pen name John Farrow, the pseudonym that Ferguson, a respected sixty-three-year-old author and playwright with six novels under his own moniker, began using twelve years ago for his crime fiction. While the new book completes a trilogy featuring his Montreal detective, Émile Cinq-Mars, River City otherwise stands a genre apart from its predecessors. It may constitute a genre apart from most novels ever published.

Even the story of how the book came into being is suitably epic. Ferguson first submitted a 1,300-page manuscript to his French and English publishers. When the editors deemed it too long, he cut it by a third. That version ran in a French translation, but editor Iris Tupholme at HarperCollins eventually decided the original novel was the superior one. In the end, they settled on a text somewhere between too big and too small.

Regardless, River City is another baggy monster. The narrative blankets nearly five centuries of Montreal history, from first contact between Cartier and the Iroquois to the October Crisis in 1970. In between lie vigorous, vivid renderings of everything from the sexual adventures of aboriginal princes in sixteenth-century France to a blow-by-blow account of the March 1955 Richard Riot through the city’s downtown. The riot has come to be viewed as the spark that ignited the Quebec nationalist movement, and a murder committed that fateful night, using a dagger that once belonged to Cartier, sets off a detective plot involving Cinq-Mars, as well as his elusive mentor, a POW camp survivor named Armand Touton.

The ensuing tale of corruption and greed among Montreal’s elite is the only formulaic component in a boldly original creation. The climax, involving Cinq-Mars and a warehouse of FLQ weapons and explosives, is apparently based on a long-held secret about the October Crisis. (The Cuban embassy owned the warehouse.) The character of Pierre Trudeau, first encountered arguing theology with a priest during the Richard Riot, is largely conjectural, the most substantial of several cameos in the book by figures from the city’s history. The “Cartier Dagger,” too, is pure invention, a device that allows Ferguson/Farrow to indulge his extravagant gifts as a fabulist.

River City, like Don Gillmor’s recent Kanata, demonstrates Canadian history as rich and engrossing, no less the stuff of great drama than other, more celebrated and bloody national narratives. For Ferguson, a direct line exists between the diplomacy of Jacques Cartier and the compromise reached to resolve the October Crisis four centuries later. To appreciate what is unique about our nation, look to that ability to negotiate ground and solve disputes, without the mayhem that generally accompanies both elsewhere on the planet.

More mainstream than Blackstrap Hawco and less phantasmagorical than The Man Game, Trevor Ferguson’s epic is at once a specific argument about history and a paean to the “New World” inhabited, geographically speaking, by all these fictions. “The shape of the world was being forever transformed,” the French king’s representative thinks on observing seals and whales in the St. Lawrence. One memorable early scene has the Iroquois struggling not to be terrified by a “poor excuse for a wolf”—a.k.a. a dog, brought from France—that can understand human speech, and will happily go fetch a moccasin. The natives see magic in this tamed beast, but it is the Europeans who are most affected by contact between the so-called Old and New Worlds. “They believe it is a great magic,” one Iroquois leader assures the other, “that we live here.”

The outsized, morally shaded Montreal of River City is cousin to Mordecai Richler’s literary hometown, with the notable addition of a far greater attention to the city’s French dimension. Ferguson’s Canada, too, is no less wild eyed and wide open than it was for Ephraim Gursky, the stowaway on the Franklin expedition who survives because he has brought his own supply of kosher food, and who later founds a millennial cult among the Eskimos.

Will the populist River City find more readers than other books of its ilk? It stands a chance, especially with the concurrent reissue of the earlier John Farrow titles City of Ice and Ice Lake. But if the novel experiences similar difficulties, it may not be on account of either its bulk or its decidedly major-key preoccupations. Two other reasons why Canadians are reluctant to embrace these mega-fictions come to mind. The simpler one concerns gender differences. The vast majority of such wrist-crippling books are written by men, and they amount to either an Ahab-like obsession, or an Ahab-like pathology—not to all tastes.

As well, the very notion of proposing a grand narrative for the Canadian experience could be the bigger problem. An ocean of earth wider than the Atlantic separates Vancouver from St. John’s. Keeping most Canadian fiction on the smaller scale might represent a psychic response to the vastness of the land. Canada may be so sprawling it has to stay, on the page at least, largely contained. The intense regionalism of Ferguson, Henderson, and Harvey is equally telling: no matter the sweep and social ambition of the novel, it still needs to pinpoint its geography, to not presume to encompass too much. It may be that we don’t think the dramas, histories, and regional dispositions of the nation-state proclaimed as “Canada” can be honestly coalesced under a single literary roof. We may even distrust such efforts, the way we distrust American grandness and the American historical narrative (unified, we tend to believe, by unrelenting propaganda and bloody conquest).

If that is true, the continental sprawl of Solomon Gursky Was Here is discordant with our self-conception, and an unwelcome challenge to it. Mordecai Richler’s nervy, diasporic Jews may wander our behemoth country, making their homes wherever they land, but they are the exception. The rule is something less intrepid, and perhaps more defeated.

This appeared in the June 2011 issue.