On the car radio, the weather report was aptly apocalyptic. Environment Canada had just issued a severe thunderstorm warning for Toronto, and already the sky north of the city had turned an ominous charcoal. Even the most cynical Hollywood scriptwriter couldn’t have dreamed up a more fitting scene-setter as a stream of cars turned into a parking lot tucked behind the Loblaws superstore at Eglinton Avenue and Don Mills Road in search of a more precise forecast on just when to expect Armageddon.

Outside the low-rise office building that houses Canada Christian College, security was tight. Yellow police tape blocked the driveway, and plainclothes rcmp officers eyed the crowd for threats to two visitors inside: Canada’s ambassador to Israel, Alan Baker, and Major General Aharon Zeevi Farkash, chief of Israel’s military intelligence. Still, neither was the night’s main draw. Taking their seats on the stage of the college’s ground-floor auditorium, they were mere warm-up acts for the undisputed star of the show: Reverend John Hagee, the Texas televangelist who packs eighteen thousand born-again Christians into his Cornerstone Church in San Antonio every Sunday and whose fire-and-brimstone broadcasts reach an estimated ninety-three million homes around the globe.

Seated onstage, Hagee hardly looked capable of mustering such charisma. A squat fire plug in a brown shirt, brown suit, and beige striped tie, he stared out from behind owlish wire rims, no hint of a smile creasing his jowls. But the moment he strode to the mike, he had the audience in thrall. “As we sit here in safety and security, a nuclear time bomb is ticking in the Middle East,” Hagee intoned, his drawl gathering decibels as he rhymed off the litany of threats against Israel from Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, including his vow to see the nation wiped off the map. “In the twenty-first century, the president of Iran is the new Hitler of the Middle East,” Hagee thundered. “I believe Israel is in the greatest hour of danger it has known since statehood.”

In his latest book, Jerusalem Countdown—on sale for $14 in the college lobby—Hagee had already spelled out the implications of that scenario, complete with supporting arguments from top intelligence sources and the Biblical prophet Ezekiel. “We are facing a countdown in the Middle East,” he wrote with urgent certitude. “It is a countdown that will usher in the end of this world.”

But on this particular May night, Hagee chose not to elaborate on that discomfiting doomsday plot—discomfiting, that is, for all but Bible-believing Christians like himself, who bank on wafting heavenward in the rapture before all the bloodshed sweeps the globe. As he had warned in Jerusalem Countdown, “We are racing toward the end of the age. Messiah is coming much sooner than you think!”

The Second Coming has always raised an awkward theological hurdle in Hagee’s quarter-century of cheerleading for Israel. Even in his disputed reading of the Bible, there are only rapture provisions for those who have accepted Jesus Christ as their personal saviour. For this audience, sprinkled with Jewish dignitaries, Hagee chose to focus on a more diplomatic, short-term action plan—one he unveiled last February when he summoned four evangelical pastors, including Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell, to San Antonio to recruit a grassroots lobby called Christians United for Israel.

This summer, as Israeli jets pounded Iranian-backed Hezbollah forces in southern Lebanon, killing an estimated 900 civilians, 3,500 of Hagee’s evangelical conscripts descended on the US capital to demand that Congress stand in solidarity with Israel. Any calls for a ceasefire ignored “God’s foreign policy statement” for the Jewish people, Hagee told the Washington crowd. “Leave Israel alone. Let them do the job.” No matter that such solidarity might fuel new waves of Islamic terrorism or, as Hagee details in Jerusalem Countdown, lead to a pre-emptive Israeli strike against Tehran’s nuclear installations, which risks igniting the final-days fuse. “I challenge you to be bold, be fearless,” he exhorted his Toronto audience. “Christians, stand up and speak up for Israel.”

To some Canadians, Hagee’s end-of-time sabre-rattling might seem like a marginal sideshow—an exotic import from the sometimes raucous big top of the US Christian right. But here, political pulse-takers seem to have overlooked the signs and portents of a shift in the landscape where fervent religious conviction and realpolitik meet. Not a word about Hagee’s Canadian visit had crept into the mainstream media, nor had its organizers run a single conventional ad. Despite that lack of publicity, two thousand evangelicals had made the pilgrimage to this suburban campus, alerted only by Christian broadcasters and church bulletins, to hear a superstar pastor with a direct pipeline to the born-again occupant of the White House. As Hagee confided to a reporter before his Toronto appearance, he first broke bread with George Bush back in the Texas statehouse, “so I know that he is with us.”

Now he has reached the same conclusion about the man ensconced at 24 Sussex Drive. On stage, Hagee lauded one of Stephen Harper’s first post-election acts: after Hamas militants won power in the Palestinian Authority, Harper became the first world leader to cut off its funding, trumping even Bush. “God has promised to bless the man, the church, the nation that blesses the Jewish people,” Hagee purred from the podium. “I am so delighted that Canada’s prime minister immediately denounced Hamas terrorism when he became the leader of this great nation.”

Hagee’s assessment of Harper isn’t based on news clips alone. His Toronto host, not to mention his longtime Canadian major-domo, was Canada Christian College president Charles McVety, one of the most outspoken players in this country’s religious right wing. During the last election, as head of a handful of pro-family lobbies including the Defend Marriage Coalition, McVety emerged as a power to be reckoned with. He bought up the rights to unclaimed Liberal websites such as josephvolpe.com and stacked a handful of Conservative nomination contests in favour of evangelical candidates adamantly opposed to same-sex matrimony, a campaign he has vowed to repeat. As Harper navigates the tricky waters of minority rule—keeping the lid on any eruptions of rhetorical fervour from the rambunctious theo-cons in his caucus—it is noteworthy that he has continued to cultivate a man regarded as the lightning rod of the Christian right. Last spring, those around the prime minister drafted McVety to help sell the government’s contentious child-care policy, and on budget day he was the personal guest of Finance Minister Jim Flaherty in the Commons’ vip gallery.

Were those gestures—like Harper’s promised vote on reopening the gay marriage debate—mere sops to a constituency that the Conservatives need to transform their mandate into a majority? Most in the Ottawa press corps see them that way—as an exercise in cynicism by a canny strategist who remains at heart an unalloyed economic conservative, a tax cutter temporarily forced to pander to a passel of holy rollers he can’t wait to shrug off.

But McVety and others on the religious right are equally convinced that Harper is one of their own. “We’ve got a born-again prime minister,” trumpets David Mainse, the founder of Canada’s premier Christian talk show, 100 Huntley Street. They see him as an image-savvy evangelical who has been careful to keep his signals to them under the media radar, but they have no doubt his convictions run deep—so deep that only after he wins a majority will he dare translate the true colours of his faith into policies that could remake the fabric of the nation. If they’re right, it remains unclear whether those convictions would turn government into a kinder, gentler guarantor of social justice for all or transform the country into a stern, narrow-minded theocracy. And what would his evangelical worldview mean for international relations?

During this summer’s Middle East war, Harper reversed decades of Canadian foreign policy with his adamant support for Israel, even after its jets smashed a clearly marked United Nations observation post, killing a veteran Canadian peacekeeper. His admirers argue that steadfastness could turn the burgeoning bond between evangelical Christians and Jews into a powerful and unprecedented alliance that could leave him unbeatable at the ballot box. But a growing chorus of critics warns that Harper has already paid a high price for that strategic calculation, irrevocably alienating Canada’s mushrooming Islamic population and leaving in shreds the country’s reputation as an even-handed peace broker. Harper’s stand has also raised more unsettling questions. What does it mean if and when a believer in the infallibility of Biblical prophecy comes to power and backs a damn-the-torpedoes course in the Middle East? Does it end up fuelling overenthusiastic end-timers who feel they have nothing to lose in some future conflagration, helping speed the world on Hagee’s fast track to Armageddon?

Fifteen minutes east of the Parliament Buildings, far from the neo-Gothic limestone of official Ottawa, the faded storefronts and fast-food joints along Montreal Road testify to working-class life in the capital. Just around the corner on Codd’s Road, next to Halley’s Service Centre, a curbside sign announces East Gate Alliance Church, the unlikely evangelical congregation that Harper attends.

The single-storey brick building still resembles the public school it once was. Stout colonial pillars have been tacked onto the front where former classrooms now house half a dozen ethnic congregations. Inside the airy sanctuary, there are no pews—only rows of stackable metal chairs beneath a simple cathedral ceiling. The pink walls, punctuated by pink blinds topped by skinny chintz swags, are the only nod to decor. No stained glass or gilt icons detract from the stark wooden cross above the stage.

On this particular Sunday, East Gate’s star parishioner is miles away, but it seems no wonder that a man with a passion for secrecy would choose this house of worship, light years from the media’s prying eyes. As members take their seats, few of the men sport jackets or ties, and kids race through the aisles to the chords of a grand piano. Suddenly a band strikes up, complete with a drum and guitars, and a young woman with a hand-held mike leads hymns whose rousing lyrics are projected onto the back wall. Halfway through the service, Pastor Bill Buitenwerf, who prefers a dark shirt and tie to his clerical collar, finally lopes to the pulpit, counselling his flock not to lose heart when the forces of darkness close in. “There’s moral degradation everywhere,” he begins, rhyming off a list of evils, including abortion, which he plans to protest at a right-to-life rally on Parliament Hill later that week. “It can be discouraging when we try to make a difference in our government,” he says, then catches himself. “Now, I’m not saying anything about our current government.”

Buitenwerf’s sermon is no barn-burner. Occasionally during a hymn, scattered worshippers lift their arms skyward, palms raised in praise, but this isn’t some emotive, revival-style service, studded with ecstatic sobs and hallelujahs. East Gate is a member of the Christian and Missionary Alliance, founded in 1887 by a Prince Edward Island–born preacher named Albert Simpson. Infused with a zeal for faith healing and more aggressive evangelizing abroad, Simpson’s breakaway sect was part of what divinity scholars call the holiness movement, which agitated for a return to Methodism’s reformist roots. Now, with more than four hundred thousand members in two thousand churches across the continent, it’s considered squarely in the evangelical mainstream. According to its Statement of Faith, adherents believe the Bible is “inerrant” and the Second Coming is “imminent.” Women are still not accepted for ordination, and a position paper on divorce does not mince words on a related matrimonial subject. “Homosexual unions are specifically forbidden,” it decrees, “and are described in Scripture as manifestations of the basest form of sinful conduct.”

Buitenwerf admits that the prime minister isn’t a regular attendee these days, but for many the surprise is that he shows up at all. For more than a decade, the man who remains an enigma to all but a trusted inner circle has kept his religious identity largely under wraps. Then last year, Lloyd Mackey, the Ottawa correspondent for a Christian news service, blew his spiritual cover. In a slim, rambling volume entitled The Pilgrimage of Stephen Harper, Mackey traced the Conservative leader’s odyssey from the blithe stolidity of the United Church in suburban Toronto where he grew up to East Gate’s makeshift metal pews.

Harper never did give Mackey a formal interview, but he had spoken publicly about his faith twice before, in both cases to small Christian outlets off the mainstream-media frequency. In February of last year, evangelical talk-show host Drew Marshall cued him on a Toronto-area station, Joy 1250. “Let’s jump into the Jesus stuff here,” Marshall said. “Rumour has it that you actually are a genuine follower of Christ.” Harper was primed for the query—relaxed, even chatty. “Yes, I became a Christian in my twenties,” he replied, before acknowledging, “I don’t talk a lot about it.” Still, he attempted to reassure secular listeners who might have tuned in. “I won’t say I always keep my faith and my politics separate,” he said, “but I don’t mix my advocacy of a political position with my advocacy of faith.”

Ten years earlier, Harper admitted to the now-defunct Ottawa Times that when he was a teenager he “would have been an agnostic central Canadian liberal,” but “life experiences” had led him to the Alliance church. He did not elaborate on those experiences, but according to others, Harper’s evangelical conversion dates back to when he was helping Preston Manning hammer out the Reform Party’s credo. Harper was fresh from his first stint in Ottawa as an aide to Conservative Member of Parliament Jim Hawkes, a solitary, disillusioning year that had shattered every certitude about the machinery of policy-making that he’d cherished. He’d fled back home only to face a traumatic breakup with his fiancée. Throwing himself into his master’s in economics, he addressed that dark night of the soul by embarking on a private intellectual quest: a crash course in philosophy.

Shortly after Manning recruited him, Harper began trying out the evangelical services that seemed to offer many of the party’s early players, especially his confidante Diane Ablonczy, such certainty. But Mackey fingers Manning himself as Harper’s chief spiritual mentor—a role that Reform’s godfather waves off. “I’d take that stuff with a little bit of a grain of salt,” Manning says. “Stephen was very unhappy about that book.” Still, Deborah Grey, Reform’s first MP and Harper’s boss during part of that period, confirms Mackey’s account. “Preston was key,” she says. “Stephen had some very long, very involved discussions with Preston in the late 1980s, early 1990s. He saw Preston and a faith that was real, and how you could marry faith and politics.”

Mackey points out that Harper is no George Bush—a traditional “born-again” who claimed a life-changing epiphany on the booze-sodden road to perdition. He calls the prime minister a “cerebral” Christian who read his way to belief. “When it came to his spiritual formation with Preston, he’d say, ‘What are the classics? ’ ” Mackey explains. “And Preston would say, ‘Try C. S. Lewis’ or, ‘Try [Malcolm] Muggeridge.’ ”

At the time, Harper’s father, Joseph—the man he calls the most important influence on his life—was facing his own spiritual crossroads. In Harper’s interview with Drew Marshall, he recalled that his father “ became quite an expert in theological matters as he grew older,” and after years as an ardent United Church–goer and elder, suddenly decamped to the Presbyterians. Harper sidestepped the question of why Joseph Harper had jumped ship but he pointedly noted that Marshall’s evangelical audience would get his drift. What he seemed to be referring to was the charged 1988 decision by the United Church General Council to approve the ordination of homosexuals—a decision that provoked thousands of defections.

In Calgary, Harper chose the same no-frills denomination that counted Manning on its rolls, but a different congregation across town: Bow Valley Alliance, which had opened modestly in the mid-eighties with seventy people praying in a public school. Three years ago, when Harper returned to Ottawa as leader of the Canadian Alliance, Bow Valley’s pastor recommended family-friendly East Gate, where a former Reform researcher, Laurie Throness—later chief of staff to Chuck Strahl, Harper’s minister of agriculture—happened to be a pianist and elder.

After word of Mackey’s book leaked out, conventional wisdom in the capital argued that Harper’s wife, Laureen, must have dragged him to East Gate. In fact, although she has attended services with her husband and two kids, Buitenwerf claims never to have met her. “She’s not interested in spiritual things,” confirms Grey. According to Mackey, it is Harper who makes sure their children, Ben and Rachel, get to Sunday school, not his wife. “Apparently, somebody in her family was a member of an evangelical sect which paid more attention to the church than to the family,” Mackey says. “It turned her off.”

Harper has been so careful not to reveal his faith that many voters were stunned when he capped off his election-night victory speech with “God bless Canada.” Was it a slip of the tongue—a case of rhetorical exuberance swamping his celebrated intellectual cool? Or, as some critics insisted, a shameless aping of every American president within recent memory, no matter their political stripe? Even New York Times correspondent Clifford Krauss noted that it was “an unusual line in a country where politicians do not customarily talk about God.”

In fact, Harper had already used the tag line as opposition leader, and he wasn’t the first prime minister to do so. On February 15, 1965, Lester Pearson jubilantly roared out the same benediction as he hoisted Canada’s first red and white maple leaf flag over the Parliament Buildings. “It’s just ridiculous to think that this is some novelty that was learned by watching Republicans on television,” scoffs Preston Manning. “This is a country that used to end every public meeting by saying, ‘God Save the Queen.’ ”

As pundits pondered the significance of Harper’s taste in exit lines, one thing seemed clear: a politician known for attempting to control his party’s every public utterance had chosen to invoke what National Post columnist Warren Kinsella dubbed “the G-word.” If, as suspected, Harper was sending a message to the country’s estimated 3.5 million evangelicals—not to mention the 44 percent of Canadians who tell pollsters they’ve committed their lives to Christ—what was he trying to tell them?

In his pre-election chat on the Drew Marshall Show, Harper managed to work in an undisguised plug: “I always make it clear that Christians are welcome in politics,” he said, “and particularly welcome in our party.” That invitation has not gone unnoticed. As Janet Epp Buckingham, director of the Evangelical Fellowship’s Ottawa office, notes, “In the last election, the media was pointing out that evangelicals are scary, and in the election before that the Liberals were doing quite a bit of fear mongering. It’s such a relief to have a party that says, ‘You guys are welcome here.’ ”

That relief translated into votes. According to an Ipsos-Reid poll in April, 64 percent of weekly Protestant churchgoers—the vast majority of them evangelicals—voted Conservative in the last election, a 24-percent jump from 2004. For the first time in the history of polling in Canada, Catholics who attend church weekly also shifted a majority of their votes from the Liberals to Harper’s party. While the Ottawa press corps has been preoccupied with Harper’s ability to keep the most blooper-prone Christians in his caucus buttoned up, he has quietly but determinedly nurtured a coalition of evangelicals, Catholics, and conservative Jews that brought him to power and that will put every effort into ensuring that he stays there. Last spring, when Ontario premier Dalton McGuinty could barely wangle an hour with him, Harper made time for dozens of faith groups, including a five-woman delegation from the Catholic Women’s League which hadn’t managed to snare a sit-down with any prime minister in twenty-four years. “Smile if you’re a so-con,” ran a headline in the Western Standard above a photo of the meeting. “Canada’s traditional Christian groups can’t say enough good things about the Tories’ social policies so far.”

Harper’s agenda turns out to be hidden only to those who don’t know where to look. Within weeks after the election, the first leak about his upcoming legislative package outlined a plan by Justice Minister Vic Toews, one of the most conservative evangelicals in his cabinet, to raise the age of sexual consent to sixteen from fourteen. The media greeted the scoop with a barely concealed yawn, but the Evangelical Fellowship, which had been lobbying for years on the issue, recognized it as a custom-tailored bulletin. Says Epp Buckingham, “We took it as a message that we were being heard.”

Borrowing a page from Bush’s White House, which boasts a deputy responsible for “Christian outreach,” Harper has installed a point man for the religious right, among other groups, in his government, under the title “director of stakeholder relations.” But evangelical activists know that a more direct route to the prime minister is through his parliamentary secretary, Jason Kenney. After the election, many in the Ottawa press corps were astonished when the Calgary loyalist who served as a critic in every recent Reform/Alliance shadow cabinet didn’t win a portfolio. But these days, Kenney may have more clout than any minister, playing emissary to groups with whom Harper doesn’t wish to leave prime ministerial fingerprints, above all on the religious right. Despite being a Catholic, Kenney is a regular on the evangelical circuit, turning up at so-con confabs and orchestrating discreet meetings with the boss. “ Jason,” says one Ottawa insider, “has a lot more influence than you might think.”

For Harper, the courtship of the Christian right is unlikely to prove an electoral one-night stand. Three years ago, in a speech to the annual Conservative think-fest, Civitas, he outlined plans for a broad new party coalition that would ensure a lasting hold on power. The only route, he argued, was to focus not on the tired wish list of economic conservatives or “neo-cons,” as they’d become known, but on what he called “theo-cons”—those social conservatives who care passionately about hot-button issues that turn on family, crime, and defence. Even foreign policy had become a theo-con issue, he pointed out, driven by moral and religious convictions. “The truth of the matter is that the real agenda and the defining issues have shifted from economic issues to social values,” he said, “so conservatives must do the same.”

Arguing that the party had to come up with tough, principled stands on everything from parents’ right to spank their children to putting “hard power” behind the country’s foreign-policy commitments, he cautioned that it also had to choose its battlefronts with care. “The social-conservative issues we choose should not be denominational,” he said, “but should unite social conservatives of different denominations and even different faiths.”

These days, though Harper seems firmly set on that theo-con path, he has every reason to see a minefield ahead. In 1989, when Preston Manning convinced him to set aside his MA studies and shepherd Deborah Grey through the Byzantine byways of Parliament, Harper and Grey sailed smack into the maelstrom of the abortion debate. Former Evangelical Fellowship president Brian Stiller calls it “the most galvanizing issue in the last twenty years”—one that makes today’s inflamed passions over same-sex marriage pale in comparison. In the wake of the Supreme Court decision striking down the law banning abortion, Stiller and Brian Mulroney’s government tried to cobble together an uneasy compromise: a bill that would have sentenced doctors to two years in prison for performing abortions when a woman’s life was not at risk, but that was not an outright ban.

Grey never made a secret of either her pro-life views or her evangelical faith—at her election-night victory party, she sang “What a day that will be / When my Jesus we shall see” with a gospel choir before network cameras—but the abortion vote posed a conundrum for her. Privately, Preston Manning shared her views, but he also made clear that her job as the solitary torchbearer of his new populist party was to represent her riding. Harper set about polling Beaver River, Alberta, and to Grey’s relief a majority of voters opposed the bill. She might have been more elated if she hadn’t been so appalled by the vitriol that was unleashed before the results were in, when she’d made clear that she might have to follow her constituents’ wishes, not her conscience. “I got more hate mail from Christians than from anybody else,” she marvels still. “I had believers come to my office and say, ‘You’re no Christian. May you rot and burn in hell.’ ”

As Manning watched last winter’s election from the sidelines, he fumed at what he likes to call the “sham tolerance” of the national media. “There was considerable receptivity to the argument that Mr. Harper comes from the wrong part of the country,” he says, “and holds these religious convictions which are dangerous.” For Manning, it brought a sense of déjà vu. In Reform’s earliest days, he’d dodged sly digs about his religious “wing nuts” and later watched as Stockwell Day, the outspoken Pentecostal who had snatched the Canadian Alliance from him, was caught in a creationist quagmire. After the cbc resurrected footage of Day opining that Adam and Eve once walked with dinosaurs, Warren Kinsella, then a Liberal operative, promptly went on TV with a purple Barney doll to crack, “I just want to say to Mr. Day that The Flintstones was not a documentary.” Day’s leadership was swamped in a gusher of guffaws. “There’s a taboo in the House of Commons that you do not talk about your deepest spiritual convictions,” Manning says in exasperation. “Part of the reason is that people who open themselves up just get hammered.”

Now Manning is doing his part to ensure that his spiritual protege and the estimated seventy evangelicals in the Conservative caucus—however well muzzled—don’t suffer the same fate. Last year, he set up the Manning Centre for Building Democracy, a $10-million Calgary-based non-profit aimed at training Conservatives how to run ridings and campaigns, then staff MPs’ offices. He calls it “a school of practical politics,” but one of the centre’s main preoccupations is tutoring the Christian evangelicals now flooding into Ottawa on how to survive the perilous waters of public life.

In February, less than a month after Harper’s victory, Manning took over Ottawa’s Holiday Inn to kick off his centre with a three-day seminar called Navigating the Faith/Political Interface. A sold-out group of more than one hundred MPs, aides, and public-policy researchers turned up to take notes at what the Ottawa Citizen dubbed “Mr. Manning’s Charm School for Unruly Christians—or What Not to Say.”

While Manning blames media hostility and intolerance for much of the fix in which evangelicals find themselves today, he also concedes that some Christians bring on their own image woes. “Some of these faith-oriented people conduct themselves in such a way that they scare the hide off the secular,” he confided later. He counselled newly elected MPs to curb their zeal. “The preference is to ride into Parliament with a speech that will peel the paint off the ceiling,” he told them, “but you’ll set your cause back fifty years.” Much of his advice amounted to spin control: ditch the God talk and avoid the temptation to play holier-than-thou. “You have to advocate righteousness,” he said, “without appearing self-righteous.”

For the seminar’s theme, Manning chose Matthew 10:16, in which Jesus is about to send his disciples out into the world “like sheep among wolves” to carry on his work. “He said, ‘I’m going to give you a few guidelines first,’ ’’ Manning explains. “And one of the major ones was, ‘Be wise as serpents and harmless as doves.’ In other words, be shrewd—be as smart as the other guy—but be gracious. Be non-threatening.” Manning promptly illustrated the difficulty of following his own advice. “In a moment of spontaneity, Mr. Manning went off his notes,” the Ottawa Citizen reported, “and said many people become gay after ‘horrific’ experience with heterosexual relationships.”

In the penthouse suite of a high-rise tower three blocks from the Parliament Buildings, Dave Quist surveys the vista unrolling beyond his corner windows. “If we could chop down the top floors of the World Exchange Plaza,” he quips, “you could see Parliament Hill.” Not that the preppy, personable Quist has any trouble accessing the corridors of power. A former Conservative candidate and Hill aide, he’s now executive director of the Institute of Marriage and Family Canada (imfc), the research arm of the Canadian branch of James Dobson’s Focus on the Family.

Last February, before Parliament had convened, the imfc’s gala launch lured more than a dozen MPs, including Stockwell Day, Harper’s new minister of public security, and Jason Kenney, who delivered a toast. It also drew protesters from the equal-marriage lobby group Egale, who denounced Dobson, a child psychologist whose Colorado Springs broadcasting empire turned him into one of the chief power brokers of the new US religious right, which put George W. Bush into the White House.

In a city where the Evangelical Fellowship had been a lone voice for the last decade, Quist’s institute is the latest and most lavishly funded of a new crop of faith-based organizations that have sprung up in the capital over the last eighteen months. Most, like the Institute for Canadian Values founded by Charles McVety, were a direct riposte to Bill C-38, which legalized same-sex marriage. “There’s no doubt it was a major lightning rod for a lot of people,” Quist says. “There was an awakening. People said, ‘Wow, how did we get here? And is it too late? Is it all set in stone?’ ”

Certainly, the Canadian debate grabbed the attention of Dobson, who worried that Canadian legislation might encourage gay rights south of the border. In his 2004 book, Marriage Under Fire, Dobson compared proponents of same-sex marriage to Adolf Hitler, and last year Focus on the Family Canada bought time on 130 radio stations for an appeal from Dobson urging Canadian voters to contact their MPs and kill Bill C-38. As Darrel Reid, the former president of Focus on the Family Canada, puts it, “He saw Canada as being on the leading edge of social decline.”

But Quist is adamant that the institute was not the brainchild of Dobson, whose lobbying might endanger its charitable tax status, and his photo is nowhere to be seen on its walls. “I’ve never met Dr. Dobson,” he says. He takes pains to underline that Focus on the Family Canada, headquartered in Langley, British Columbia—the heart of the Canadian Bible Belt—is an autonomous entity. That claim was undercut when the Montreal Gazette examined the US ministry’s annual reports and discovered that it had contributed computer, broadcast, and telephone support services to its Canadian spinoff valued at $1.6 million over four years.

With an operating budget of $500,000, the institute’s sleek penthouse is three floors above Conservative Party headquarters and accessible only by a private elevator or stairway. “If what you’re doing is substantial, you have to look substantial,” says Reid, the driving force behind establishing the Ottawa office. “Ottawa is where the lawmakers are. You can’t be four thousand miles away. Nobody was listening to us out in Langley.”

A former chief of staff to Preston Manning, Reid had turned his seven-year Focus presidency into a bully pulpit on social issues before stepping down last year to run as a Conservative candidate in Richmond, BC. But he insists that the institute is not a lobbying arm. “We’re not an activist organization,” agrees Quist. “We’re not going to be organizing petitions or rallies on the Hill.”

Quist paints the institute merely as a vehicle to provide lawmakers with helpful information to better argue their case, whether on spanking—the subject of Dobson’s 1970 bestseller Dare to Discipline—or assisted suicide, which social conservatives see as the next major front in the culture wars. His inspiration, he claims, is not Dobson’s controversial Washington arm, the Family Research Council, whose president told a Washington gathering of conservatives last year that the federal judiciary posed a greater threat to democracy than terrorist groups. Instead, for a role model Quist looked to that provocative bastion of economic conservatism, Vancouver’s Fraser Institute. “When they started twenty-five years ago, they were viewed with great skepticism,” he points out. “Now they’re quoted all the time.”

Despite the institute’s research mission, Reid wanted a seasoned political player in the pilot’s seat. A born-again Christian who spent six years as executive assistant to Reed Elley, the Reform/Alliance MP from Nanaimo-Cowichan, Quist more than fit the job description. In 2004, when Elley resigned, Quist ran for his seat and, after losing, spent last year as operations manager in Harper’s office. That resumé might seem more essential to a lobbyist than a think-tank chief, but Quist had learned how to draft cram notes for MPs and their aides. “I knew if we could make the research into bite-sized chunks—clearly written with five or six bullets or talking points—it would be invaluable,” he says. “No twenty-page report is going to get read.”

The debut edition of the glossy imfc Review had the prescience—or insider knowledge—to focus on Harper’s first thorny legislative issue: child care. Still, it took an unusual tack for an organization trying to stake out a reputation for research. The lead article, entitled “Don’t Get Fooled By Child Care Research,” argued that most studies advocating public daycare “tend to be ideologically motivated and researcher bias is frequent.… Beware.” The article went on to attack Martha Friendly, coordinator of the Childcare Resource and Research Unit at the University of Toronto—which it noted was federally funded—for harbouring “a strong bias towards government-funded, non-profit daycare.” That slap singled out a commentator who was guaranteed to be a leading critic of Harper’s proposal to hand every family a $1,200-per-child allowance instead of expanding public daycare.

Quist hand-delivered the imfc Review to MPs’ offices, starting with old Conservative pals like Cheryl Gallant, who used it in a press release. He also made sure to get it to those MPs whose votes might be up for grabs. “For those who are neutral,” he says, “I’m hoping it will be a tipping point.”

On the day of the Throne Speech, Quist was one of more than a dozen guests at a festive pre-event lunch in the parliamentary restaurant hosted by Senator Anne Cools, a vocal social conservative in Harper’s caucus. There had been no mention of a business agenda in the initial invitation, but Cools’ guest list included some of the country’s most muscular so-con voices, including McVety and Gwen Landolt of real Women of Canada. During lunch, the conversation turned to how the assembled invitees might beat the drums for Harper’s family allowance. Some welcomed it as a hint of later tax credits for private religious education; others saw it as a windfall for stay-at-home moms and the growing number of evangelicals—like Quist and his wife—who had chosen home-schooling. Two weeks later, a headline in the Globe & Mail trumpeted, “Social conservatives to sell Tory daycare plan.”

Some participants denied they’d agreed to any such thing. Harper’s office disavowed organizing the lunch, insisting it was a coincidence that Jason Kenney had dropped by, but his spokeswoman conceded, “We’re reaching out to all interest groups who agree with our child care plan.” real Women’s Landolt was not as shy. “When the thing arises on the drawing board,” she told the Globe, “we’ll be there.”

On budget day, when Finance Minister Jim Flaherty firmed up the legislative nuts and bolts of the child-care allowance, Dave Quist was also there— in Spin Central, the vast holding pen where reporters troll for reactions to government proposals from assembled lobbyists and interest groups. The next morning he was quoted in the Globe lauding the plan as “a significant positive step for families.”

Quist insists the imfc is no Harper cheering section. Ready to open its doors last fall, it delayed the launch until after the election. As Derek Rogusky, Quist’s British Columbia–based boss, confides, “We didn’t want to be seen as a policy arm of the Conservative party.” Besides, Rogusky points out, “People of faith don’t see Stephen Harper as their messiah. They don’t feel he’s going to change everything they want.”

For many evangelicals, the real measure of Harper is not his first budget, with its crowd-pleasing bonanza of cash; it’s the one he brings down if and when he secures a majority. Will he answer the demand of some in the Christian right and ensure that a portion of the new daycare spaces he has promised to create are run by religious communities? More importantly, will he follow Bush’s lead and begin to dismantle the federal social safety net, turning the job of being one’s brother’s keeper over to faith-based do-gooders?

In the United States, Dobson has urged parents to abandon the public school system, which he sees as a breeding ground for secular humanism, hostile to the Book of Genesis and prayer. “I hope I live to see the day when, as in the early days of our country, we won’t have any public schools,” agreed Jerry Falwell, the founder of the Moral Majority that helped sweep Ronald Reagan into power. “The churches will have taken them over again, and Christians will be running them.”

Those may be long-term aspirations, but the US religious right has learned that patience pays off. Many of the conservative think tanks that were seeded to supply intellectual heft and respectability to the burgeoning right wing under Reagan have not only outlived him, they have provoked a shift in popular discourse that now gives the religious right a hold on both houses of Congress. As Darrel Reid makes clear, the imfc isn’t pinning all its hopes on Harper. “The fact that there’s a government that’s more sympathetic is good,” he says. “But that government won’t be there forever. That’s why we need to be there for the long haul.”

At 7:30 on a drizzly June morning, the Confederation Room—the largest and most ornate hall on Parliament Hill—was already crammed to capacity with more than four hundred MPs, civil servants, and their guests, all of whom have turned up for the National Prayer Breakfast. An overflow crowd of 150 was being shepherded into an adjoining salon with closed-circuit video screens. Those numbers might not mean much in Washington—where the annual mega-event of the same name draws more than three thousand, including the president, making it the highlight of the social calendar for the Christian right—but this year’s turn-out was the largest in the forty-year history of the Ottawa breakfast.

Jack Murta, the former Mulroney cabinet minister who now runs the event, attributes the enthusiasm to a new breed of more committed Conservative evangelicals in the House. So many flocked to his weekly parliamentary prayer breakfasts earlier this year that he had to encourage some to drop out. “It was getting unwieldy,” he says.

Not that there is a shortage of prayer meetings on Parliament Hill. The Conservative caucus has its own Thursday-morning Bible study class, and for the last three decades civil servants have gathered for prayer groups in almost every department, including three in Defence. Even Jack Layton’s New Democratic Party has created a faith and social justice caucus.

But the newest prayer hub in the capital is also the most improbable: a missionary delegation to the federal government led by Rob Parker, a pastor from Vernon, BC, who feels he’s received a divine calling to bring prayer to the country’s leaders—and, not coincidentally, to help them see the error of their ways. Last year, in a stately neo-Romanesque convent formerly occupied by Les Filles de la Sagesse, Parker and his wife, Fran, opened the National House of Prayer. In its handsome panelled salons, weekly prayer teams who’ve flown in from churches across the country send up supplications for the nation. Fanning out across the city on prayer walks, they end up in the Commons’ visitors’ gallery for Question Period three times a week. Except for their rapt expressions of concentration, they might be just any other tourist group. They don’t bow their heads or kneel. “You don’t have to have your eyes closed to pray,” Fran Parker points out.

National unity is a frequent topic, and they’ve offered “strategic prayers” for Trade Minister David Emerson as he wrestles Washington over the softwood lumber dispute—an issue key to many of the Parkers’ supporters in BC. They’ve also prayed for the nation’s security with Stockwell Day, one of their biggest supporters in cabinet. “We say, ‘Let’s cover our waterways,’ ” Rob Parker explains. “ ‘Let’s cover our nuclear plants.’ ” The teams often drop by MPs’ offices, offering a takeout prayer service, but the Parkers try to avoid naming the parliamentarians they’ve prayed with, or the subjects on which they’ve pleaded for intercession. “You have to be careful with the non-Christian media,” Fran confides. “A reporter kept asking us whether we prayed about same-sex marriage. No way we’re going there.”

In some political circles, the National House of Prayer might be dismissed as a marginal Christian outpost, but Stephen Harper’s Ottawa has put out the official welcome mat. Jack Murta invited Fran Parker to address a seminar after the National Prayer Breakfast, and every Friday afternoon the couple runs a prayer meeting in the Parliament Buildings’ chapel, just across the street from the pmo. Even though he’s never had an official meeting with the prime minister, Rob Parker says he has “certainly shared with him in passing—in the hallways or whatever. He was very glad we’re doing what we’re doing.”

A Pentecostal who believes that God’s will is revealed to believers in portents and prophetic utterances, above all when they speak in tongues, Parker had embarked on a seventy-three-day prayer walk from Calgary to Ottawa six years ago with a charismatic Christian group called Watchmen for the Nations. When the walkers arrived in Ottawa, Parker prayed for God’s mercy on the nation and, as his wife tells it, “Rob looked around and thought, ‘Man, all these embassies, but I don’t see an embassy of prayer here.’ ”

Still, it took the 9/11 attack to convince Parker that his mission couldn’t wait. Watching evangelist Billy Graham lead Washington’s national memorial service, he was shocked when he switched channels to Ottawa’s commemorative rites. “There was no mention of God,” he says. “I found out later in the newspapers that the name of God or Jesus was not allowed to be used. We were too multicultural.” As Parker recounts on the National House of Prayer website, “I cried out to God that Canada has become a ‘Godless nation’ and asked Him to intervene.”

The Parkers talked up the notion of a prayer embassy across the country, but two years ago they were ready to give up when they received a divine thumbs-up. The morning after they’d read a passage from Jeremiah about the siege of Jerusalem, a newspaper headline on the Liberals’ sponsorship scandal proclaimed, “Paul Martin under siege.” For Fran Parker it was an unmistakable prophetic sign. “We thought, ‘Yes, it’s a siege of righteousness,’ ” she says. “We realized it was a wake-up call: we’ve got to make things right.”

Last year, when they discovered the abandoned convent, they knew it was the building they’d been praying for when a real-estate agent pointed at the Chinese embassy out the back door. “That’s China behind you,” he said—the very phrase uttered by a prominent Pentecostal preacher who had singled out the Parkers during one of his Ottawa revival services. But the $900,000 price tag was too steep and the demand for a $500,000 down payment daunting. Then Christian broadcaster Dick Dewart invited the Parkers to appear on his Alberta-based Miracle Channel. Within days of the show, they’d raised $300,000, and a Chinese evangelical congregation in Toronto kicked in with a $225,000 interest-free loan. “We represent thousands in the land,” Fran Parker says.

Now the Parkers host as many as thirty-five prayer activists a week who pay their own travel expenses and donate $20 to $50 a night for room and board in return for a unique glimpse of the capital. When they’re not on Parliament Hill, they can often be found praying inside the Supreme Court, whose rulings have sparked so much evangelical outrage. This summer, the activists focused their spiritual attention on the offices of those MPs who might be wavering on whether to support reopening the same-sex marriage debate. But their most frequent destination is the Peace Tower, where they pray beneath the nation’s motto inscribed on one wall—a motto inspired directly by the Bible.

In 1867, as the Fathers of Confederation were wrangling over what to call their newfangled federal entity, Samuel Tilley, the premier of New Brunswick, sat down for his morning devotions when his Bible fell open at Psalm 72, verse 8: “He shall have dominion also from sea to sea, And from the River to the ends of the earth.” Tilley and his fellow pols took it as divine intervention. Ever since, that defining verse has inspired Pentecostal and charismatic Christian groups such as the Parkers’ to believe that the Dominion of Canada has a destiny linked to scriptural prophecy.

It’s a controversial view—and never more so than now. This spring, in Kingdom Coming: the Rise of Christian Nationalism, New York writer Michelle Goldberg traced the growing influence of American fundamentalists who embrace what’s known as dominion theology, calling for a society where civil law is replaced by Biblical prescriptions and born-again Christians take over the task of governing to prepare for the thousand-year dominion of Christ. Their first skirmish in that struggle has centred on restoring religious terminology not only to holidays like Christmas, but to official discourse. Goldberg warns that many of those “dominionists” not only have ties to the Bush White House, but seem determined to turn the US into a theocracy. “It makes no sense to fight religious authoritarianism abroad,” she writes, “while letting it take over at home.”

The Parkers are careful to dismiss the notion that theocratic designs lie behind their National House of Prayer. “It’s not about getting a Christian government or a Christian nation,” Fran Parker says. “It’s about praying for our leaders to restore the nation to righteousness.” But in a relaxed moment after the National Prayer Breakfast, she admits that she believes Canada has a divinely inspired destiny—a covenant with God that has been broken by governments that failed to stop practices such as abortion that “defile the land.” She’s convinced that the nation has received a prophetic warning to return to its Christian roots.

She has not the slightest doubt that celestial nudge came last May 24 when the Peace Tower clock stopped at 7:28 a.m.—precisely the number of the psalm and verse that gave the country its designation and motto. “And what day did it stop?” Parker asks, underlining her point. “Victoria Day! On the news that night, they said it might take seventy-two hours to fix,” she says, pausing for effect. “Seventy-two!” she marvels. “Just so you get it!”

In his corner suite on the fourth floor of Canada Christian College, the ebullient Charles McVety is hanging up from a long-distance call to a Conservative MP. “A lot of our friends are in government now,” he confides, “so that makes a lot of things easier.” So cozy is McVety with Harper’s team, in fact, that last June he arranged an honorary degree for Stockwell Day from Russia’s St. Petersburg State University.

From his suburban Toronto office festooned with frothy fake-flower bouquets, pictures of fighter jets, and a scale model of the Avro Arrow, McVety wears so many hats it’s not always clear from which pulpit he’s speaking. On the wall behind his desk, framed front pages of the National Post testify to his staunch opposition to Bill C-38 under headlines such as “Faiths Unite Against Same Sex.” Sometimes he’s cited as the president of this college where twelve hundred students—three hundred of them full-time—pursue Bible-based studies in a former pension-fund building from which McVety broadcasts his weekly TV shows. Other times, he’s the voice of the Defend Marriage Coalition, thirteen religious and activist organizations—including real Women of Canada and Campaign Life—on whose behalf he stormed the country last year aboard the red and white Defend Marriage bus with his wife and their seven-year-old daughter. On one of his many websites, McVety recounts that adventure under the title, “Daddy, Why Are They Spitting At Us? ” Now, the bus sits in the college’s parking lot, ready for the next campaign. McVety has vowed to wrest Conservative nominations from candidates reluctant to vote out same-sex marriage legislation. One sure target: maverick Conservative Garth Turner, who compared McVety’s nomination threat to the modus operandi of the Taliban.

Occasionally, McVety pops up in the media as president of the Canada Family Action Coalition (cfac), whose mission is “to see Judeo-Christian moral principles restored in Canada.” Co-founded ten years ago by Brian Rushfeldt, a Calgary pastor who’d acquired his theology degree from Canada Christian College by correspondence, cfac has become a ten-thousand-member grassroots lobby known for publishing election guides that track MPs’ votes on social issues, as well as for Rushfeldt’s periodic appearances on Jerry Falwell’s Old Time Gospel Hour. But last year McVety decided it was time to create a new Ottawa-based think tank with more of an academic gloss: the Institute for Canadian Values (icv). Why the need for so many outfits? “On the left, there are hundreds of organizations,” he says, “and on the right there is a great void.”

Funded by a $250,000 gift from a retired trucking magnate named Sidney Harkema, the new institute was prompted in part by McVety’s impatience with the Evangelical Fellowship, which published a guide for clergy on just how far they could go fighting Bill C-38 without incurring Revenue Canada’s wrath. McVety scoffs at that scrupulousness. “There’s nothing in the regulations that says we’re second-class citizens not allowed to have a voice,” he says.

To head the icv, McVety tapped someone who shared his taste for a more boisterous approach: Joseph Ben-Ami, an Orthodox Jew who’d been B’nai Brith’s point man in Ottawa and a top operative in Stockwell Day’s leadership campaigns. A ubiquitous presence at Conservative and evangelical gatherings, Ben-Ami emerged during last spring’s child-care debate as more than just a quotable source defending Harper’s family allowance. He showed up brandishing Access to Information documents charging that some advocates of public daycare, including the Caledon Institute, had received Liberal government funding. “It’s a con game,” Ben-Ami declared, “and Canadian taxpayers are the victims.”

McVety’s ideological muscle-flexing has provoked charges that he’s financed by the US Christian right. “We haven’t seen one American greenback,” he retorts. Still, his critics could be forgiven for leaping to conclusions. Canada Christian College houses nearly two dozen evangelical tenants, including Oral Roberts Ministries, and just down the hall from McVety’s own office he runs John Hagee’s Canadian command post, dispensing books and dvds that he claims bring in $1 million a year. When McVety visits his televangelist chums south of the border, he says, they’re “appalled” by this country’s legislative developments. “They all say, ‘What’s happened to you?’ ” he reports. “ ‘You’re legalizing gay marriage, you’re legalizing marijuana. You’ve become extremists.’ ”

McVety has turned to key strategists who choreographed the religious right’s takeover of the Republican Party to help stop that drift. Two years ago, he imported Jerry Falwell for an “Emergency Pastors Briefing” to rally four hundred evangelical clergymen against a bill that included making denunciations of homosexuality a hate crime. Then last December, still smarting from their failure to stop Bill C-38, McVety and Ben-Ami launched the Institute for Canadian Values with a gala dinner tutorial from Ralph Reed, the boyish tactical wizard behind Pat Robertson’s Christian Coalition, which succeeded Falwell’s Moral Majority and helped mobilize the South for Bush. With nearly two million believers in his grassroots guerrilla force, Reed terrified liberal Republicans with his organizational stealth. “I paint my face and travel at night,” he once boasted. “You don’t know it’s over until you’re in a body bag. You don’t know until election night.”

By the time Reed appeared at Canada Christian College, his influence was waning. His bid to become Georgia’s lieutenant-governor was foundering, and he was embroiled in the casino-lobbying scandals that sent his sometime business partner, Jack Abramoff, to prison. But his appearance a day after the federal election call drew a sold-out crowd of evangelical and Conservative activists, including Senator Anne Cools and McVety’s old friend Jim Flaherty who, as Ontario’s attorney general, had once called for jailing the homeless.

Reed warned his audience that “if the people of the church don’t get involved, somebody else will,” and urged them not merely to organize meticulously, but to be bold. “He said, ‘Never run and hide,’ ” McVety recounts. “Never allow anyone to tell you family values are a liability. They’re only a liability in the media, never at the ballot box.” But Reed also offered a lesson on how to take over a nomination contest or a riding. “He taught us all that only a handful of people actually go and seriously volunteer to get someone elected,” McVety says. “We’re talking about 150 people per riding. Tiny numbers! This is the size of a small church.”

McVety sprang into action. He and activists like Tristan Emmanuel, head of Equipping Christians for the Public Square, focused on a few dozen ridings scattered across the country. McVety himself zeroed in on one particular target: Mark Holland, the Liberal MP in his own riding of Ajax-Pickering, outside Toronto, who had organized the pivotal caucus petition that convinced Paul Martin to push Bill C-38 through before the Commons’ summer recess last year. McVety helped engineer the nomination of Rondo Thomas, his longtime deputy at the college, as the Conservative candidate over two better-known rivals. But as soon as Holland’s backers released video footage of Thomas describing an apocalyptic ideological battle between “those who believe in righteousness and those who believe in immorality,” the pastor vanished from the hustings—apparently not of his own free will. McVety rails against the Conservative campaign war room that “locked him down,” as he put it. “They’re afraid of a hostile, vicious media that hates Christians.”

Holland sailed to victory in the election, but the campaign left him shaken. At one point, he received a call from McVety, who queried, “How are your constituents going to feel about you not being married?” Almost no one knew that Holland and the mother of his three children had never tied the knot in their fourteen years together. The MP was stunned. “To me it was a veiled threat,” he says.

Holland lodged a complaint with Revenue Canada about Canada Christian College, whose president, McVety, was listed as the registered owner of nearly two dozen websites taken out in the name of leading Liberals who had supported same-sex marriage, including Don Boudria, Belinda Stronach, and Holland himself. As it turned out, this was not the first time the college had found its actions under scrutiny. In 1976, McVety’s father, Elmer, a Toronto evangelist who had founded a Bible school named Richmond College, the predecessor of Canada Christian College, was the subject of a probe by the Toronto Star after donors to his charity, International Outreach, complained they had trouble getting tax receipts. Elmer McVety admitted to the Star that although he’d assured contributors that “arrangements are now completed for the distribution of thousands of copies of the Scriptures in Arabic,” he had not yet located an Egyptian printer for the project.

Six years later, the Ontario ministry of education revoked the right of Canada Christian College to grant degrees. That accreditation battle raged on after McVety’s death in 1993, when his son Charles took over and purchased the college’s current home for $2.1 million. Five years later, the education ministry ordered the college to shut its doors. As McVety likes to recount, “I told them to take a long walk on a short pier and get lost.”

He casts the fight as a ministry vendetta, which he finally ended with the intercession of some pals in Mike Harris’s Conservative government. In May 1999, Frank Klees, a former Baptist pastor who was in Harris’s cabinet, introduced a bill finally conferring legal status on McVety’s school. That year, McVety made a $1,000 donation to Klees’ re-election campaign.

Ironically, one of the major stumbling blocks to the college’s accreditation was a charge levelled by the Canadian Jewish Congress (cjc) that some of McVety’s courses were aimed at converting Jews. McVety calls this a terrible misunderstanding, but it lasted seven years. Only after he agreed to close the college’s Jewish studies department and dismiss two faculty members did the cjc drop its objections. Still, it may not be entirely coincidental that in 1991, the year of the cjc’s initial complaint, McVety hooked up with John Hagee, whose Texas TV ministry had made a name for itself as a cheerleader for Israel.

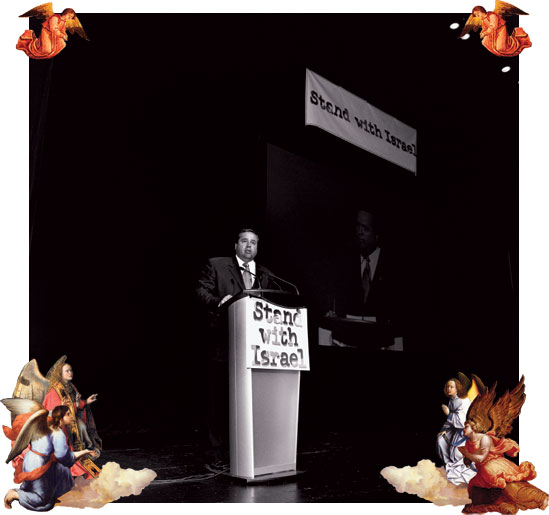

Now McVety has emerged as one of Israel’s leading champions in this country. He has co-hosted an Israel-bonds dinner at Canada Christian College and this summer, as some liberal evangelicals were taking to the streets to protest Israel’s devastation of Lebanon, McVety was the chief speaker from the evangelical right at a massive “Stand with Israel” rally organized by, among others, his old nemesis, the Canadian Jewish Congress.

McVety’s preoccupation with Israel has become the thread that knits together his whirlwind organizational activities, from the fundamentalist theology that the college dispenses to the curiously wide-ranging agenda of the Institute for Canadian Values, where Ben-Ami fires out press releases on subjects as apparently disparate as same-sex marriage and Hamas terrorist threats. Both issues are concerns shared by the intensely conservative wings of the Christian and Jewish communities that rally around McVety and his closest collaborator, Frank Dimant, executive vice-president of B’nai Brith Canada, who has an honorary doctorate from Canada Christian College on his office wall.

Dimant and McVety’s mutual interest in Israel and family values is exactly what Stephen Harper had in mind three years ago in his Civitas speech when he laid out his plans for a new Conservative coalition that would unite social conservatives across faith lines. For those who can’t see the connection between so-con issues and Israeli security, McVety offers one practised sound byte. “Israel is the number one family-values issue,” he says. “Where does marriage come from? God. Where does the Bible come from? Israel. The first family of Christianity—Jesus, Mary, and Joseph—were all Jewish. Israel is the source of everything we have.”

But the connection is considerably more complex, turning on a controversial theological doctrine that argues the apocalypse is just around the corner. Christian Zionists like Hagee and McVety, who embrace it, insist that the end of the world is due any day. How soon? “We’re about three seconds before midnight,” McVety says, “and this bond [between evangelicals and Jews] is part and parcel of it.”

On McVety’s desk sits the sort of souvenir usually found in Jerusalem tourist shops: a chunky, foot-long silver-and-gilt replica of the city crowned by what Jews call the Temple Mount but, as home to two mosques, Al-Aqsa and the Dome of the Rock, erected where Mohammed is believed to have ascended to heaven, it is also regarded as the third-holiest site in Islam. But to both Jews and evangelical Christians, the Temple Mount is equally sacred as a prophetic construction site: the spot where the ancient Biblical Temple of Solomon must be rebuilt before the Messiah can return. They may differ on whether it’s the Second Coming of Christ or the arrival of Judaism’s own long-awaited Messiah, but their shared interest in that charged patch of Jerusalem real estate has spawned an alliance that has become one of Israel’s political and economic lifelines.

In 2004, more than four hundred thousand evangelical tourists flocked to Israel, outnumbering any other visitor group, including North American Jews. According to Israeli sources, they poured an estimated $1.4 billion into the economy. So vital has the influx of Christian Zionists become that the Knesset now boasts a Christian Allies Caucus, and the Jerusalem Post has launched a new monthly Christian edition. “It’s a tremendous message of solidarity,” says Canada’s ambassador to Israel, Alan Baker. As Joseph Ben-Ami points out, “The Jewish community in Canada is 380,000 strong; the evangelical community is 3.5 million. The real support base for Israel is Christians.”

Hagee’s congressional lobbying blitz in Washington last July was, in fact, directly inspired by a strategic blueprint drafted by former Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin three decades ago. At a time when Washington was pressuring Israel to relinquish the West Bank and East Jerusalem and create an independent Palestinian state, an Israeli report fingered the US evangelical community as Tel Aviv’s best hope to counter those demands. In 1978, Begin invited Hagee and other American televangelists to Jerusalem to point out their common theological stake in the geography they saw as essential to the unfolding of Biblical prophecy. As Hagee likes to say, he went as a tourist and “came back a Zionist.” Three years later, when Israel’s bombing of Iraq’s nuclear reactor provoked a global outcry, Hagee held his first rally for Israel in San Antonio. Since then, both the Moral Majority and Pat Robertson’s Christian Coalition have made support for Israel a key plank in their domestic political mandate. As Falwell told 60 Minutes, the American Bible belt is “Israel’s safety belt.”

In Canada, one of the chief links in that safety belt is Reverend John Tweedie, an evangelical pastor from Brantford, Ontario, who now chairs a Netherlands-based charity called Christians for Israel International. Not only does Tweedie lead regular tours to the Holy Land, but his group has also sponsored the immigration of hundreds of Jews from the former Soviet Union to settlements in Gaza and the West Bank. Four years ago, Tweedie teamed up with B’nai Brith to organize Canada’s first joint mission to Israel by Jews and evangelicals. It was no coincidence that he chose to partner with one of the most conservative wings of the Jewish community. Like most Christian Zionists, Tweedie opposes the creation of a Palestinian state or an Israeli pullout from Gaza and the West Bank. “I have a Biblical worldview,” he says, “so I don’t agree with trading land for peace.”

Tweedie’s efforts and those of dozens of other evangelical tour groups since have forged extraordinary bonds between faiths. On one fact-finding mission to Israel, Frank Dimant and Jason Kenney, then an opposition MP, were about to enter the Palestinian stronghold of Ramallah when they ran into Jibril Rajoub, Yasser Arafat’s security chief. Kenney nudged Dimant and suggested a quick revision of the B’nai Brith official’s title: the MP introduced Dimant to the Palestinian as his aide.

Despite these bonds, some Jews remain deeply suspicious of Christian Zionists and the theology that fuels their zeal: the theories of a nineteenth-century rebel deacon named John Nelson Darby, the father of dispensationalism. On repeated missions to North America between 1862 and 1877—some of which included pulpit stops in Toronto—Darby touted a new scriptural timeline based on a vision he’d had after falling off a horse. Arguing that the world was already in the penultimate era of seven Biblical epochs or “dispensations,” he warned that only true believers would be saved in a secret rapture—tugged heavenward before a seven-year period of turmoil known as the tribulation, when the Antichrist seizes global power. Once that false Messiah had been vanquished in battle at Armageddon, Christ would return to Jerusalem triumphant and usher in a millennium of peace.

Darby’s end-times scenario, once scorned as marginal, sparked a surge of interest after the founding of Israel in 1948. For many evangelicals, the creation of a Jewish homeland on Biblical acreage was the fulfillment of a prophecy that warned the “budding” of the fig tree—a symbol representing Israel in parables—was a portent that the Second Coming was at hand. They pinpointed Armageddon taking place on the present-day hilltop plain of Har-Megiddo, near Haifa.

As dispensationalists took over the postwar evangelical movement, many detected other hints of Darby’s millennial script being played out in the headlines. Ernest Manning, Preston’s father, frequently cited Darby’s apocalyptic vision in his radio sermons on Canada’s Back to the Bible Hour. For Manning—as for Ronald Reagan, another fan of dispensationalism—there was no doubt that the Book of Daniel’s “wicked king of the north” was the godless Soviet Union. Since its implosion, candidates for the dispensationalist Antichrist have been updated more than once: the secretary-general of the United Nations and the head of the European Community have been displaced by Saddam Hussein and now the president of Iran.

Thanks to the Left Behind series of Christian thrillers co-authored by Tim LaHaye, a Republican operative who helped found the Moral Majority, Darby’s theology has been tarted up with a contemporary, high-tech gloss and devoured by more than forty-two million readers. In the latest instalment, The Rapture, released in June, Rayford Steele, an airline pilot, steers his 747 above the smoking debris and collapsed communication towers left behind after millions of Christians have been snatched out of their homes and cars in one cataclysmic whoosh.

That plot line is exactly what has spooked many in the Jewish community: despite the affection Hagee and other evangelicals profess, Darby’s script does not include a clear exit strategy for those who haven’t accepted Christ as the Messiah. Even Hagee and Falwell have ended up hurling accusations at one another in the Israeli press over just how Jews fit into the dispensationalist salvation scheme. Tweedie prefers to dodge the question. “We don’t find it profitable to get too specific about end-times prophecy,” he says.

Theologians in most mainstream Prot-estant denominations debunk Darby’s scriptural timeline as an outrageous misreading of the Bible. Even leading evangelical scholar Donald Wagner, professor of religious and Middle Eastern studies at Chicago’s North Park University, calls it “a modern heresy with cultish proportions.” For a growing number of critics like Wagner, what’s most alarming about the wildfire spread of dispensationalism is not its trendiness but the fact that it is now embraced by many who either control or exercise leverage over the corridors of power. “The danger is that when people believe they ‘know’ how things are going to turn out and then act on those convictions, they can make these prophecies self-fulfilling and bring on some of the things they predict,” says Reverend Timothy Weber, the author of On the Road to Armageddon: How Evangelicals Became Israel’s Best Friend.

What could a dispensationalist worldview mean for global politics? In the 1980s, Washington’s foreign-policy establishment worried that Reagan’s flirtation with end-time beliefs, including branding the Soviet Union “the evil empire,” would hasten the nuclear apocalypse that he periodically referred to as inevitable. To speed the day, dispensationalists like Falwell who helped bring him to power were among the loudest voices urging Reagan on a course of brinkmanship.

George Bush has reignited many of the same fears with his rhetoric of righteousness in launching the invasion of Iraq and his war against the “evil-doers” of global terrorism. Congress has become controlled by ardent Christian Zionists like former majority leader Tom DeLay, who opposes the creation of a Palestinian state and once told an Israeli audience, “I don’t see occupied territory; I see Israel.”

Writer and TV journalist Bill Moyers, himself an ordained Baptist minister, has raised another equally urgent fear about the dispensationalist hold on domestic policy. In a speech to Harvard’s Center for Health and the Global Environment last year, he warned that millions of Christian fundamentalists have no interest in protecting the environment or putting the brakes on global warming. “They believe that environmental destruction is not only to be disregarded,” Moyers said, “but actually welcomed—even hastened—as a sign of the coming apocalypse.”

That thesis might sound alarmist, but last year when superstar pastor Rick Warren, author of the bestselling The Purpose Driven Life, joined other evangelical leaders calling for action against global warming, they were slammed by James Dobson, who declared that the scientific evidence against carbon dioxide emissions remains unproven. Besides, Dobson said, the issue was a distraction from the more pressing evangelical preoccupation with family values.

For Charles McVety, any mention of the environmental movement sparks a tirade against the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. “The Bible talks about a false religion and one-world government, and what we have developed is exactly that,” McVety rages. “The false religion is the worship of Mother Earth—I call them earthies!” He dismisses Rio’s Earth Charter as “that pagan document.”

Did those same views colour Stephen Harper’s decision to bow out of the Kyoto Protocol? Have Harper’s private spiritual impulses as an evangelical shaped any of his policy decisions, whether on child care or boosting the defence budget and backing Israel unequivocally in the Middle East? The answer isn’t clear, nor may it ever be. Not only is Harper notoriously guarded about his motivations, but many of the items on his agenda that have won the applause of the religious right in Canada so far have coincided with the demands of other more traditional groups in the expanding tent of his new Conservative coalition.

In the end, it may not matter to what extent Harper himself buys into the beliefs of his evangelical backers. By wagering his political fortunes on their goodwill, he is already, like Bush, to some extent their captive. It may be less important to know whether Harper personally cares about avoiding an epic clash in the Middle East than to discover what political ious he has to a core constituency that has no interest at all in peace for the region—at least until the Second Coming.

Even before the Israeli offensive in Lebanon, Canadian voters were registering a newfound wariness of letting religion seep into politics. A survey for CanWest News Service conducted three months after Harper’s election showed that the number of respondents who said they’d vote for an evangelical prime minister had dropped over the last decade from 80 to 63 percent. Pollster Andrew Grenville attributed some of that disenchantment to Bush’s example in the United States, where a flurry of new books by American evangelicals is decrying the politicization of their faith. The title of a recent release by Randall Balmer, a professor of religion at Barnard College in New York City, sums up the growing unease: Thy Kingdom Come: How the Religious Right Distorts the Faith and Threatens America—an Evangelical’s Lament. But Grenville also blamed part of the Canadian wariness on what he called “the Stephen Harper factor.”

Could it be that Harper has tied the Conservatives’ future to a strategic faith-based alliance modelled after one that is already beginning to backfire on his ideological soulmate in the White House? If so, he might consider reading the full text that Preston Manning recommended for believers setting out on the high-risk road of public activism. Christ’s coaching session for his apostles as recounted in Matthew 10:16 offers a caution on the volatile affections of apparent allies: “Be wise as serpents and harmless as doves,” it counsels, “but beware of men, for they will deliver you up to councils and scourge you in their synagogues.”